Unit - 1

Introduction

TQM can have an important and beneficial effect on employee and organizational development. By having all employees focus on quality management and continuous improvement, companies can establish and uphold cultural values that create long-term success to both customers and the organization itself. TQM’s focus on quality helps identify skills deficiencies in employees, along with the necessary training, education or mentoring to address those deficiencies.

With a focus on teamwork, TQM leads to the creation of cross-functional teams and knowledge sharing. The increased communication and coordination across disparate groups deepens institutional knowledge and gives companies more flexibility in deploying personnel.

Benefits of TQM

The benefits of TQM include:

- Less product defects. One of the principles of TQM is that creation of products and services is done right the first time. This means that products ship with fewer defects, which reduce product recalls, future customer support overhead and product fixes.

- Satisfied customers. High-quality products that meet customers’ needs results in higher customer satisfaction. High customer satisfaction, in turn, can lead to increased market share, revenue growth via upsells and word-of-mouth marketing initiated by customers.

- Lower costs. As a result of less product defects, companies save cost in customer support, product replacements, field service and the creation of product fixes. The cost savings flow to the bottom line, creating higher profit margins.

- Well-defined cultural values. Organizations that practice TQM develop and nurture core values around quality management and continuous improvement. The TQM mindset pervades across all aspects of an organization, from hiring to internal processes to product development.

During the early days of manufacturing, an operative’s work was inspected and a decision made whether to accept or reject it. As businesses became larger, so too did this role, and full-time inspection jobs were created. Accompanying the creation of inspection functions, other problems arose:

- More technical problems occurred, requiring specialised skills, often not possessed by production workers

- The inspectors lacked training

- Inspectors were ordered to accept defective goods, to increase output

- Skilled workers were promoted into other roles, leaving less skilled workers to perform the operational jobs, such as manufacturing.

These changes led to the birth of the separate inspection department with a “chief inspector”, reporting to either the person in charge of manufacturing or the works manager. With the creation of this new department, there came new services and issues, e.g., standards, training, recording of data and the accuracy of measuring equipment. It became clear that the responsibilities of the “chief inspector” were more than just product acceptance, and a need to address defect prevention emerged. Hence the quality control department evolved, in charge of which was a “quality control manager”, with responsibility for the inspection services and quality control engineering. In the 1920’s statistical theory began to be applied effectively to quality control, and in 1924 Shewhart made the first sketch of a modern control chart. His work was later developed by Deming and the early work of Shewhart, Deming, Dodge and Romig constitutes much of what today comprises the theory of statistical process control (SPC). However, there was little use of these techniques in manufacturing companies until the late 1940’s. At that time, Japan’s industrial system was virtually destroyed, and it had a reputation for cheap imitation products and an illiterate workforce. The Japanese recognised these problems and set about solving them with the help of some notable quality gurus – Juran, Deming and Feigenbaum. In the early 1950’s, quality management practices developed rapidly in Japanese plants, and become a major theme in Japanese management philosophy, such that, by 1960, quality control and management had become a national preoccupation.

By the late 1960’s/early 1970’s Japan’s imports into the USA and Europe increased significantly, due to its cheaper, higher quality products, compared to the Western counterparts.

In 1969 the first international conference on quality control, sponsored by Japan, America and Europe, was held in Tokyo. In a paper given by Feigenbaum, the term “total quality” was used for the first time, and referred to wider issues such as planning, organisation and management responsibility. Ishikawa gave a paper explaining how “total quality control” in Japan was different, it meaning “companywide quality control”, and describing how all employees, from top management to the workers, must study and participate in quality control. Companywide quality management was common in Japanese companies by the late 1970’s. The quality revolution in the West was slow to follow, and did not begin until the early 1980’s, when companies introduced their own quality programmes and initiatives to counter the Japanese success. Total quality management (TQM) became the centre of these drives in most cases. In a Department of Trade & Industry publication in 1982 it was stated that Britain’s world trade share was declining and this was having a dramatic effect on the standard of living in the country. There was intense global competition and any country’s economic performance and reputation for quality was made up of the reputations and performances of its individual companies and products/services. The British Standard (BS) 5750 for quality systems had been published in 1979, and in 1983 the National Quality Campaign was launched, using BS5750 as its main theme. The aim was to bring to the attention of industry the importance of quality for competitiveness and survival in the world market place. Since then, the International Standardisation Organisation (ISO) 9000 has become the internationally recognised standard for quality management systems. It comprises a number of standards that specify the requirements for the documentation, implementation and maintenance of a quality system. TQM is now part of a much wider concept that addresses overall organisational performance and recognises the importance of processes. There is also extensive research evidence that demonstrates the benefits from the approach. As we move into the 21st century, TQM has developed in many countries into holistic frameworks, aimed at helping organisations achieve excellent performance, particularly in customer and business results. In Europe, a widely adopted framework is the so-called “Business Excellence” or “Excellence” Model, promoted by the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM), and in the UK by the British Quality Foundation (BQF).”

‘Quality’ is generally referred to a parameter which decides the inferiority or superiority of a product or service. It is a measure of goodness to understand how a product meets its specifications. Usually, when the expression “quality” is used, we think in the terms of an excellent product or service that meets or even exceeds our expectations. These expectations are based on the price and the intended use of the goods or services. In simple words, when a product or service exceeds our expectations, we consider it to be of good quality. Therefore, it is somewhat of an intangible expression based upon perception.

W. Edwards Deming, Armand V. Feigenbaum and Joseph M. Juran jointly developed the concept of TQM. Initially, TQM originated in the manufacturing sector but it can be applied to all organizations.

The concept of TQM states that every employee works towards the improvement of work culture, services, systems, processes and so on to ensure a continuing success of the organization.

TQM is a management approach for an organization, depending upon the participation of all its members (including its employees) and aiming for long-term success through customer satisfaction. This approach is beneficial to all members of the organization and to the society as well.

When it comes to measuring the quality of your services, it helps to understand the concepts of product and service dimensions. Users may want a key board that is durable and flexible for using on the wireless carts. Customers may want a service desk assistant who is empathetic and resourceful when reporting issues.

Quality is multidimensional. Product and service quality are comprised of a number of dimensions which determine how customer requirements are achieved. Therefore, it is essential that you consider all the dimension that may be important to your customers.

Product quality has two dimensions

- Physical dimension - A product's physical dimension measures the tangible product itself and includes such things as length, weight, and temperature.

- Performance dimension - A product's performance dimension measures how well a product works and includes such things as speed and capacity.

While performance dimensions are more difficult to measure and obtain when compared to physical dimensions, but the efforts will provide more insight into how the product satisfies the customer.

Like product quality, service quality has several dimensions.

- Responsiveness - Responsiveness refers to the reaction time of the service.

- Assurance - Assurance refers to the level of certainty a customer has regarding the quality of the service provided.

- Tangibles - Tangibles refers to a service's look or feel.

- Empathy - Empathy is when a service employee shows that she understands and sympathizes with the customer's situation. The greater the level of this understanding, the better. Some situations require more empathy than others.

- Reliability - Reliability refers to the dependability of the service providers and their ability to keep their promises.

The quality of products and services can be measured by their dimensions. Evaluating all dimensions of a product or service helps to determine how well the service stacks up against meeting the customer requirements.

SERVQUAL

About the SERVQUAL (or RATER) Model

(Note: This model is also referred to as the RATER model, which stands for the five service factors it measures, namely: reliability, assurance, tangibles, empathy and responsiveness.)

As is indicated by the name of this model, SERVQUAL is a measure of service quality. Essentially it is a form of structured market research that splits overall service into five areas or components.

The SERVQUAL model features in many services marketing textbooks, usually when discussing customer satisfaction and service quality. It was developed in the mid 1980’s by well-known academic researchers in the field of services marketing, namely Zeithaml, Parasuraman and Berry. Note one of their original journal papers has been uploaded by a university.

DESIGNED FOR SERVICE FIRMS

The SERVQUAL model was initially designed for use for service firms and retailers. In reality, while most organizations will provide some form of customer service, it is really only service industries that are interested in understanding and measuring service quality. Therefore, SERVQUAL takes a broader perspective of service; far beyond simple customer service.

One of the drivers for the development of the SERVQUAL model was the unique characteristics of services (as compared to physical products). These unique characteristics, such as intangibility and heterogeneity, make it much harder for a firm to objectively assess its quality level (as opposed to a manufacturer who can inspect and test physical goods). The development of this model provided service firms and retailers with a structured approach to assess the set of factors that influence consumers’ perception of the firm’s overall service quality.

Service quality, while being interrelated with customer satisfaction, is actually a distinct concept.

Please see the discussion of the difference between service quality and customer satisfaction.

Service quality is the consumer’s assessment of overall delivery and value of the firm, which the SERVQUAL model splits into five main categories as discussed in the next section.

SERVQUAL’s Five Dimensions

As later suggested by the original developers of the SERVQUAL model, the easy way to recall the five dimensions are by using the letters of RATER, as follows:

R = Reliability

A= Assurance

T = Tangibles

E = Empathy

R = Responsiveness

According to the original academic journal article:

- Tangibles refers to physical facilities, equipment and appearance of personnel

- Reliability is the firm’s ability to perform the promise service accurately and dependably

- Responsiveness is the firm’s willingness to help customer and provide prompt service

- Assurance is knowledge and courtesy of employees and their ability to inspire trust and confidence

- Empathy is caring and individualized attention paid to customers

Servqual or rater model

SERVQUAL’s 22 Questions

When the SERVQUAL model was originally developed and researched it consisted of 22 questions (as also discussed on this website) under the five RATER dimensions. Like any piece of academic research, there is always debate and modifications over time of the appropriate factors/questions to use. Please keep in mind that 97 factors were originally considered and only the ones that were helpful (able to discriminate between firms) remained in the model.

This study initially looked at four different service industries, namely, banking, credit cards, repairs and maintenance, and telephone companies.

SERVQUAL’S TWO PARTS OF THE QUESTIONNAIRE

The SERVQUAL questionnaire is split into two main sections:

1. Respondents are asked about their expectations of the ideal service firm in that service category.

In this case, the questions would be reworded to state a particular industry, such as banking, or hotels, or education. There is no reference to a specific firm at this stage; instead, respondents are asked about the ideal firm to deal with.

This is done to frame expectations for that service category and to establish a benchmark for comparison. By working through the RATER elements, it can be seen that there would be significant differences in expectations across service industries. For example, for banking firms, assurance would be important, for medical firms, empathy would be important, and for hotels, tangibles would be important.

2. Respondents are then asked about the service quality delivery of specific firms in that industry.

This approach provides the researcher with:

- A comparison of perceived service quality levels between competing firms,

- The difference between expected and delivered service quality for each firm, and

- The ability to drill down to the 22 questions to determine where a specific firm is performing above/below expectations or competitor quality levels.

Total Quality Management (TQM) is a management framework based on the belief that an organization can build long-term success by having all its members, from low-level workers to its highest-ranking executives, focus on improving quality and, thus, delivering customer satisfaction.

TQM requires organizations to focus on continuous improvement, or kaizen. It focuses on process improvements over the long term, rather than simply emphasizing short-term financial gains.

The TQM framework was developed by management consultant William Deming who introduced it to the Japanese manufacturing industry. Today, Toyota is perhaps the best example of the TQM framework in action. The carmaker has a “customer first” focus and a commitment to continuous improvement through “total participation”.

In the early 1980s when organizations in the West started to be seriously interested in quality and its management, many attempts to construct lists and TQM frameworks to help this process.

In the West the famous American ‘gurus’ of quality management like W. Edwards Deming, Joseph M. Juran and Philip B. Crosby, started to try to make sense of the labyrinth of issues involved. Moreover, it included the tremendous competitive performance of Japan’s manufacturing industry.

Above all, Deming and Juran had contributed to building Japan’s success in the 1950s and 1960s. However, it was appropriate that they should set down their ideas for how organizations could achieve success.

Juran’s ten steps to quality improvement

- Firstly, building awareness of the need and opportunity for improvement.

- Then, set goals for improvement.

- After that, organizing to reach the goals (establish a quality council, identify problems, select projects, appoint teams, designate facilitators).

- Then, providing training.

- Moreover, carrying out projects to solve problems.

- Then, reporting progress.

- Giving recognition.

- Communicating with results.

- Keeping score.

- Lastly, maintaining momentum by making annual improvement part of the regular systems and processes of the company.

Four absolutes of Phil Corsby as a Quality Director of ITT

- Firstly, definition – conformance to requirements.

- Then, system – prevention.

- After that, performance standard – zero defects.

- Lastly, measurement – price of non-conformance.

He also offered management 14 steps to improvement:

- Make it clear that management is committed to quality.

- Form quality improvement teams with representatives from each department.

- Determine where current and potential quality problems lie.

- Evaluate the cost of quality and explain its use as a management tool.

- Raise the quality awareness and personal concern of all employees.

- Take actions to correct problems identified through previous steps.

- Establish a committee for the zero defects program.

- Train supervisors to actively carry out their part of the quality improvement program.

- Hold a ‘zero defects day’ to let all employees realize that there has been a change.

- Encourage individuals to establish improvement goals for themselves and their groups.

- Encourage employees to communicate to management the obstacles they face in attaining their improvement goals.

- Recognize and appreciate those who participate.

- Establish quality councils to communicate on a regular basis.

- Do it all over again to emphasize that the quality improvement program never ends.

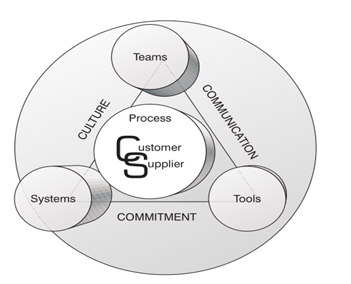

Basics TQM Framework

TQM approaches to the direction, policies and strategies of the business or organization. Moreover, these ideas were captured in a basic framework. Above all, the TQM model was in demand in the UK through the activities of the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) programs. And, the customer/supplier or ‘quality chains and the processes that were within them was the core of this TQM model.

Above all, this simple framework was useful and it was helpful for groups of senior managers throughout the world get started with TQM. Moreover, the key was to integrate the TQM activities, based on the framework, into the business or organization strategy

Edward Deming

Deming’s 14 Points on Quality Management, or the Deming Model of Quality Management, a core concept on implementing total quality management (TQM), is a set of management practices to help companies increase their quality and productivity.

W. EDWARDS DEMING’S 14 POINTS

- Create constancy of purpose for improving products and services.

- Adopt the new philosophy.

- Cease dependence on inspection to achieve quality.

- End the practice of awarding business on price alone; instead, minimize total cost by working with a single supplier.

- Improve constantly and forever every process for planning, production and service.

- Institute training on the job.

- Adopt and institute leadership.

- Drive out fear.

- Break down barriers between staff areas.

- Eliminate slogans, exhortations and targets for the workforce.

- Eliminate numerical quotas for the workforce and numerical goals for management.

- Remove barriers that rob people of pride of workmanship, and eliminate the annual rating or merit system.

- Institute a vigorous program of education and self-improvement for everyone.

- Put everybody in the company to work accomplishing the transformation.

These total quality management principles can be put into place by any organization to more effectively implement total quality management. As a total quality management philosophy, Dr. Deming’s work is foundational to TQM and its successor, quality management systems.

What is the Deming Application Prize?

The Deming Application Prize is an annual award presented to a company that has achieved distinctive performance improvements through the application of TQM. Regardless of the types of industries, any organization can apply for the Prize, be it public or private, large or small, or domestic or overseas. Provided that a division of a company manages its business autonomously, the division may apply for the Prize separately from the company.

There is no limit to the number of potential recipients of the Prize each year. All organizations that score the passing points or higher upon examination will be awarded the Deming Application Prize.

Companies Qualified for Receiving the Prize

The Deming Application Prize is given to applicant companies or divisions of companies (applicant companies hereafter) that effectively practice TQM suitable to their management principles, industry, business and scope. More specifically, the following evaluation criteria are used for the examination to determine whether or not the applicant companies should be awarded the Prize:

1) Reflecting their management principles, industry, business, scope and business environment, the applicants have established challenging and customer-oriented business objectives and strategies under their clear management leadership.

2) TQM has been implemented properly to achieve business objectives and strategies as mentioned Item 1) above.

3) As an outcome of Item 2), outstanding results have been obtained for business objectives and strategies as stated in Item 1).

How to apply for the Deming Application Prize—Due date: January 15th

The application form, which is provided at the end of this booklet, must be completed and submitted with necessary documents.

The application deadline is January 15th.

Examination

- The Deming Application Prize Subcommittee examines and selects the candidates for the Prize.

- A document examination will be carried out based on the Description of TQM Practices submitted by the applicant company. If the applicant company passes the document examination, an on-site examination will be conducted. The Subcommittee makes judgment according to the evaluation criteria and reports the results to the Deming Prize Committee.

- The examination process is not open to the public, and all possible measures are taken to ensure the confidentiality of applicant companies.

Determination of the winners—Mid October

According to the report by the Subcommittee, the Deming Prize Committee determines the winners of the Prize and notifies them.

In the event that the applicant has not attained passing points, final judgment is reserved and, unless the applicant requests withdrawal, the status is considered as “continued examination.” Subsequent examinations are limited to twice during the next three years.

Public announcement of the winners—Mid October

After the Prize winners have been determined by the Deming Prize Committee as mentioned above, the winners are announced in the following publications and the reasons for receiving the Prize are stated:

1) The “Nippon Keizai Shimbun” (Japan Economic Journal)

2) The monthly magazine “Quality Management” (published by JUSE)

3) The monthly magazine “JUSE News” (JUSE Newsletter)

4) JUSE Home Page

Award ceremony—Mid November

The winners receive the Deming Medal with an accompanying Certificate of Merit from the Deming Prize Committee. The winners also receive a written report on the examination findings (including recommendations for future improvement of their TQM activities.)

Best practices presentations by prize winners—Mid November

The winners’ best practices presentations follow the award ceremony the next day.

Status Report and On-Site Review Three Years after Receiving the Prize

The prize-winning company is requested to submit a short report on the status of its TQM practices three years after having received the prize. As a rule, an on-site review for about half-day will be conducted based on the report.

In lieu of this review, the winning company may chose the following to further promote and develop its TQM:

1) To receive TQM Diagnosis by the Deming Prize Committee Members.

2) To receive the examination for the Japan Quality Medal.

As for the details, please contact the Secretariat for the Deming Prize Committee.

For more detailed information about the application procedures and the examination criteria, please refer to “The Deming Prize Application Guide”, can be downloaded on Deming Prize main page.

J. Juran

The Juran Trilogy, also called Quality Trilogy, was presented by Dr. Joseph M. Juran in 1986 as a means to manage for quality. The traditional approach to quality at that time was based on quality control, but today, the Trilogy has become the basis for most quality management best practices around the world.

In essence, the Juran Trilogy is a universal way of thinking about quality—it fits all functions, all levels, and all product and service lines. The underlying concept is that managing for quality consists of three universal processes:

- Quality Planning (Quality by Design)

- Quality Control (Process Control & Regulatory)

- Quality Improvement (Lean Six Sigma)

The Juran Trilogy diagram is often presented as a graph, with time on the horizontal axis and cost of poor quality on the vertical axis.

The initial activity is quality planning, or as we refer to it today, ‘quality by design’ – the creation of something new. This could be a new product, service, process, etc. As operations proceed, it soon becomes evident that delivery of our products is not 100 percent defect free. Why? Because there are hidden failures or periodic failures (variation) that require rework and redoing.

In the diagram, more than 20 percent of the work must be redone due to failures. This waste is considered chronic—it goes on and on until the organization decides to find its root causes and remove it. We call it the Cost of Poor Quality. The design and development process could not account for all unforeseen obstacles in the design process.

Under conventional responsibility patterns, the operating forces are unable to get rid of the defects or waste. What they can do is to carry out control—to prevent things from getting worse, as shown. The figure shows a sudden sporadic spike that has raised the failure level to more than 40 percent. This spike resulted from some unplanned event such as a power failure, process breakdown, or human error.

As a part of the control process, the operating forces converge on the scene and take action to restore the status quo. This is often called corrective action, troubleshooting, firefighting, and so on. The end result is to restore the error level back to the planned chronic level of about 20 percent.

The chart also shows that in due course the chronic waste was driven down to a level far below the original level. This gain came from the third process in Juran’s Trilogy—improvement. In effect, it was seen that the chronic waste was an opportunity for improvement, and steps were taken to make that improvement.

Quality Planning (Quality by Design)

The design process enables innovation to happen by designing products (goods, services, or information) together with the processes—including controls—to produce the final outputs. Today many call this Quality By Design or Design for Six Sigma (DFSS)

The Juran Quality by Design model is a structured method used to create innovative design features that respond to customers’ needs and the process features to be used to make those new designs. Quality by Design refers to the product or service development processes in organizations.

Quality Improvement (Lean Six Sigma)

Improvement happens every day, in every organization—even among the poor performers. That is how businesses survive—in the short term. Improvement is an activity in which every organization carries out tasks to make incremental improvements, day after day. Daily improvement is different from breakthrough improvement. Breakthrough requires special methods and leadership support to attain significant changes and results.

It also differs from planning and control as it requires taking a “step back” to discover what may be preventing the current level of performance from meeting the needs of its customers. By focusing on attaining breakthrough improvement, leaders can create a system to increase the rate of improvement. By attaining just a few vital breakthroughs year after year (The Pareto Principle), the organization can outperform its competitors and meet stakeholder needs.

As used here, “breakthrough” means “the organized creation of beneficial change and the attainment of unprecedented levels of performance.” Synonyms are “quality improvement” or “Six Sigma improvement.” Unprecedented change may require attaining a Six Sigma level (3.4 ppm) or 10-fold levels of improvement over current levels of process performance. Breakthrough results in significant cost reduction, customer satisfaction enhancement and superior results that will satisfy stakeholders.

Quality Control (Process Control & Regulatory)

Compliance or quality control is the third universal process in the Juran Trilogy.

The term “control of quality” emerged early in the twentieth century. The concept was to broaden the approach to achieving quality, from the then-prevailing after-the-fact inspection (detection control) to what we now call “prevention (proactive control).” For a few decades, the word “control” had a broad meaning, which included the concept of quality planning. Then came events that narrowed the meaning of “quality control.” The “statistical quality control” movement gave the impression that quality control consisted of using statistical methods. The “reliability” movement claimed that quality control applied only to quality at the time of test but not during service life.

Today, the term “quality control” often means quality control and compliance. The goal is to comply with international standards or regulatory authorities such as ISO 9000.

The Juran Trilogy has evolved over time in some industries. This evolution has not altered the intent of the trilogy. It only changes the names. For instance, traditional goods producers call it QC, QI and QP while another may say QA/QC, CI and DFSS. The Trilogy continues to be the means to present total quality management to all employees looking to find a way to keep it simple.

P. Crosby’s philosophy.

Philip Crosby (1926-2001) was an influential author, consultant and philosopher who developed practical concepts to define and communicate quality and quality improvement practices. His influence was extensive and global. He wrote the best-seller Quality is free in 1979, at a time when the quality movement was a rising, innovative force in business and manufacturing. In the 1980s his consultancy company was advising 40% of the Fortune 500 companies on quality management.

Key theories

Quality, Crosby emphasised, is neither intangible nor immeasurable. It is a strategic imperative that can be quantified and put back to work to improve the bottom line. Acceptable quality or defect levels and traditional quality control measures represent evidence of failure rather than assurance of success. The emphasis, for Crosby, is on prevention, not inspection and cure. The goal is to meet requirements on time, first time and every time. He believes that the prime responsibility for poor quality lies with management, and that management sets the tone for the quality initiative from the top.

Crosby's approach to quality is unambiguous. In his view, good, bad, high and low quality are meaningless concepts, and the meaning of quality is conformance to requirements. Non-conforming products are ones that management has failed to specify or control. The cost of non-conformance equals the cost of not doing it right first time, and not rooting out any defects in processes.

Zero defects do not mean that people never make mistakes, but that companies should not begin with allowances or sub-standard targets with mistakes as an in-built expectation. Instead, work should be seen as a series of activities or processes, defined by clear requirements, carried out to produce identified outcomes.

Systems that allow things to go wrong - so that those things have to be done again - can cost organisations between 20% and 35% of their revenues, in Crosby's estimation.

His seminal approach to quality was laid out in Quality is free and is often summarised as the 14 steps:

The 14 steps

- Management commitment: The need for quality improvement must be recognised and adopted by management, with an emphasis on the need for defect prevention. Quality improvement is equated with profit improvement. A quality policy is needed which states that '… each individual is expected to perform exactly like the requirement or cause the requirement to be officially changed to what we and the customer really need.'

- Quality improvement team: Representatives from each department or function should be brought together to form a quality improvement team. These should be people who have sufficient authority to commit the area they represent to action.

- Quality measurement: The status of quality should be determined throughout the company. This means establishing quality measures for each area of activity that are recorded to show where improvement is possible, and where corrective action is necessary. Crosby advocates delegation of this task to the people who actually do the job, so setting the stage for defect prevention on the job, where it really counts.

- Cost of quality evaluation: The cost of quality is not an absolute performance measurement, but an indication of where the action necessary to correct a defect will result in greater profitability.

- Quality awareness: This involves, through training and the provision of visible evidence of the concern for quality improvement, making employees aware of the cost to the company of defects. Crosby stresses that this sharing process is a - or even the - key step in his view of quality.

- Corrective action: Discussion about problems will bring solutions to light and also raise other elements for improvement. People need to see that problems are being resolved on a regular basis. Corrective action should then become a habit.

- Establish an ad-hoc committee for the Zero Defects Programme: Zero Defects is not a motivation programme - its purpose is to communicate and instil the notion that everyone should do things right first time.

- Supervisor training: All managers should undergo formal training on the 14 steps before they are implemented. A manager should understand each of the 14 steps well enough to be able to explain them to his or her people,

- Zero Defects Day: It is important that the commitment to Zero Defects as the performance standard of the company makes an impact, and that everyone gets the same message in the same way. Zero Defects Day, when supervisors explain the programme to their people, should make a lasting impression as a 'new attitude' day.

- Goal setting: Each supervisor gets his or her people to establish specific, measurable goals to strive for. Usually, these comprise 30-, 60-, and 90-day goals.

- Error cause removal: Employees are asked to describe, on a simple, one-page form, any problems that prevent them from carrying out error-free work. Problems should be acknowledged within twenty-four hours by the function or unit to which the problem is addressed. This constitutes a key step in building up trust, as people will begin to grow more confident that their problems will be addressed and dealt with.

- Recognition: It is important to recognise those who meet their goals or perform outstanding acts with a prize or award, although this should not be in financial form. The act of recognition is what is important.

- Quality Councils: The quality professionals and team-leaders should meet regularly to discuss improvements and upgrades to the quality programme.

- Do it over again: During the course of a typical programme, lasting from 12 to18 months, turnover and change will dissipate much of the educational process. It is important to set up a new team of representatives and begin the programme over again, starting with Zero Defects Day. This 'starting over again' helps quality to become ingrained in the organisation.

The barriers to TQM are as follows-

1. Competitive markets

A competitive market is a driving force behind many of the other obstacles to quality. One of the effects of a competitive market is to lower quality standards to a minimally acceptable level. This barrier to quality is mainly a mental barrier caused by a misunderstanding of the definition of quality. Unfortunately, too many companies equate quality with high cost. Their definition leads to the assumption that a company can’t afford quality. A broader definition needs to be used to look at quality, not only in the company’s product, but in every function of the company. All company functions have an element of quality. If the quality of tasks performed is poor, unnecessary cost is incurred by the company and, ultimately, passed to the customer. TQM should work by inspiring employees at every level to continuously improve what they do, thus rooting out unnecessary costs. Done correctly, a company involved with TQM can dramatically reduce operating costs. The competitive advantage results from concentrating resources (the employees’ brainpower) on controlling costs and improving customer service.

2. Bad attitudes/abdication of responsibility/management infallibility

The competitive environment, poor management practice, and a general lack of higher expectations have contributed to unproductive and unhealthy attitudes. These attitudes often are expressed in popular sayings, such as “It’s not my job” and “If I am not broken, don’t fix it. Such attitude sayings stem from the popular notion that management is always right and therefore employees are” only supposed to implement management decisions without questioning. Lethargy is further propagated through management’s failure to train employees on TQM fundamentals that build better attitudes by involving them in teams that identify and solve problems. Such training can transform employees from being part of the problem to part of the solution. This will foster motivation and creativity and build productive and healthy attitudes that focus employees on basic fundamentals, such as: keep customer needs in mind, constantly look for improvements, and accept personal responsibility for your work.

3. Lack of leadership for quality

Excess layers of management quite often lead to duplication of duty and responsibility. This has made the lower employees of an organization to leave the quality implementation to be a management’s job. In addition, quality has not been taken as a joint responsibility by the management and the employees. Coupled with the notion that management is infallible and therefore it is always right in its decisions, employees have been forced to take up peripheral role in quality improvement. As a result, employees who are directly involved in the production of goods or delivery of services are not motivated enough to incorporate quality issues that have been raised by the customers they serve since they do not feel as part of the continuous process of quality improvement. Moreover, top management is not visibly and explicitly committed to quality in many organizations.

4. Deficiency of cultural dynamism

Every organization has its own unique way of doing things. This is defined in terms of culture of the organization. The processes, the philosophy, the procedures and the traditions define how the employees and management contribute to the achievement of goals and meeting of organizational objectives. Indeed, sticking to organizational culture is integral in delivery of the mission of the organization. However, culture has to be reviewed and for that matter re-adjustments have to be done in tune with the prevailing economic, political, social and technological realities so as to improve on efficiency. In adequate cultural dynamism has made total quality implementation difficult because most of the top-level management of many organizations are rigid in their ways of doing things.

5. Inadequate resources for total quality management

Since most companies do not involve quality in their strategic plan, little attention is paid to TQM in terms of human and financial resources. Much of the attention is drawn to increasing profit margins of the organization with little regard as to whether their offers/ supply to customers is of expected quality. There is paltry budgetary allocation made towards employee training and development which is critical for total quality management implementation. Employee training is often viewed as unnecessary cost which belittles the profits margins which is the primary objective for the existence of businesses and as a result TQM has been neglected as its implementation “may not necessarily bring gains to the organization in the short term”.

6. Lack of customer focus.

Most strategic plans of organizations are not customer driven. They tend to concentrate much on profit-oriented objectives within a given time frame. Little (if any) market research is done to ascertain the product or service performance in the market relative to its quality. Such surveys are regarded by most organizations as costly and thus little concern is shown to quality improvement for consumer satisfaction.

7. Lack of effective measurement of quality improvement

TQM is centred on monitoring employees and processes, and establishing objectives that anticipate the customer's needs so that he is surprised and delighted. This has posed a considerable challenge to many companies. Measurement problems are caused by goals based on past substandard performance, poor planning, and lack of resources and competitor-based standard. Worse still, the statistical measurement procedures applied to production are not applicable to human system processes.

8. Poor Planning

The absence of a sound strategy has often contributed to ineffective quality improvement. Duran noted that deficiencies in the original planning cause a process to run at a high level of chronic waste. Using data collected at then recent seminars, Duran (1987) reported that although some managers were not pleased with their progress on their quality implementation agenda, they gave quality planning low priority. As Oakland (1989) said, the pre-planning stage of developing the right attitude and level of awareness is crucial to achieving success in a quality improvement program.

Newell and Dale (1990) in their study observed that a large number of companies are either unable or unwilling to plan effectively for quality improvement. Although many performed careful and detailed planning prior to implementation, not one of the firms studied or identified beforehand the stages that their process must endure. Perhaps the root cause of poor plans and specifications is that many owners do not understand the impact that poor drawings have on a project’s quality, cost, and time. Regardless of the cause, poor plans and specifications lead to a project that costs more, takes longer to complete, and causes more frustration than it should. Companies using TQM should always strive towards impressing upon owners the need to spend money and time on planning. If management took reasonable time to plan projects thoroughly and invest in partnering to develop an effective project team, a lot could be achieved in terms of product performance as these investments in prevention- oriented management can significantly improve the quality of the goods or services offered by an organization

9. Lack of management commitment

A quality implementation program will succeed only if top management is fully committed beyond public announcements. Success requires devotion and highly visible and articulate champions. Newell and Dale (1990) found that even marginal wavering by corporate managers was sufficient to divert attention from continuous improvement. Additionally, Schein (1991) reported that the U.S. Quality Council is most troubled by the lack of top management commitment in many companies.

Lack of commitment in quality management may stem from various reasons. Major obstacles include the preoccupation with short-term profits and the limited experience and training of many executives. Duran, for example, observed that many managers have extensive experience in business and finance but not in quality improvement. Similarly, Bothe (1988) pointed out that although the CEO does not have to be a quality expert, programs fail when the CEO does not recognize the contribution these techniques make toward profitability and customer satisfaction.

Top management should, therefore, embrace quality improvement programs no matter how far reaching the programs may appear the monetary implications therein. Competition alone should not be considered as the single factor that drives managers into implementing quality initiatives.

10. Resistance of the workforce

A workforce is often unwilling to embrace TQM for a variety of reasons. Oakland (1989) explained that a lack of long-term objectives and targets will cause a quality implementation program to lose credibility.

Keys (1991) warned that an adversarial relationship between management and non-management should not exist, and he emphasized that a cooperative relationship is necessary for success. A TQM project must be supported by employee trust, acceptance and understanding of management's objectives. Employees, therefore, should be recognized by the management as vital players in the decision-making processes regarding to quality improvement as involving them would have motivating effect on implementation of quality programs.

11. Lack of proper training/Inadequate Human Resource Development

There is evidence that lack of understanding and proper training exists at all levels of any organization, and that it is a large contributor to worker resistance. Schein (1990), for example, mentioned that business school failure to teach relevant process skills contributed to manager ineffectiveness’s requires a well-educated workforce with a solid understanding of basic math, reading, writing and communication. Although companies invest heavily in quality awareness, statistical process control, and quality circles, often the training is too narrowly focused. Frequently, Duran’s warning against training for specific organizational levels or product lines is unheeded. This has also been underscored by Newell and Dale who argue that poor education and training present a major obstacle in the development and implementation of a quality program. . For a company to produce a quality product, employees need to know how to do their jobs. For TQM to be successful, organizations must commit to training employees at all levels. TQM should provide comprehensive training, including technical expertise, communication skills, small-team management, problem-solving tools, and customer relations.

The quality statement deals with this problem. You may already have a quality statement for general use in your business or you can create one as part of your response to a tender. It should help to convince the buyer that you are the right supplier for their needs.

A quality statement lays out your firm's working practices and commitment to providing a good service. It should explain how effective and efficient your methods for carrying out the project will be.

What does a quality statement include?

Typically, a quality statement covers issues such as:

- How you would approach and manage the project;

- Your quality management system, and whether you are accredited to any standards (e.g., ISO 9001);

- Compliance with legal requirements, and your policies in areas such as health and safety, equality and sustainability;

- The qualifications and experience of key personnel;

- Previous experience on similar projects, including references.

Often, the buyer will tell you what information you need to include in your quality statement - for example, asking you to include a copy of your health and safety policy - and explain how your quality statement will be assessed.

Bear in mind that quality management systems are not the same as quality statements. A quality management system is a way of measuring your firm's internal processes, often with external accreditation from bodies such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). If you have systems or standards like this in place, you should include details as part of your quality statement, but you must also provide the other information you are asked for.

Supplying complete information is essential: if you do not, your bid will probably be ruled out, no matter how good it is in other areas.

Customer focus is just one aspect of Top-Quality Management and refers to paying keen attention to improving customer satisfaction which is aimed at customer retention, increasing customer loyalty, while at the same time increasing profits in the business, company or organization. It is about incorporating the customer’s opinion into creation of a service or product and getting employees to look at the process of service or product creation through the eyes of the customer. Customer satisfaction does not come easy and calls for application of customer relations management. There is a common saying that customer is always king and true to it, businesses thrive depending on how well they treat their customers. Satisfied customers will not only keep coming back for more, but they will also bring along other customers, hence making the business popular and helping it to gain a competitive advantage over competitor.

Implementing customer focus

Stakeholders have explored new ways of improving student performance especially at the university level, where a big proportion of students with poor performance are placed. It is after witnessing the success that comes with customer-oriented business approaches that resulted into improvements in service delivery and better customer awareness in other businesses that educators and other stakeholders in the field of education have come together to try and implement the customer-oriented approach into education systems. It has come to the realization of education stakeholders that parents and students need to be treated as valued customers who are constantly seeking services from universities as organizations.

One of the key scholars who discussed the core importance of customer focus and its application in the school setting was Deming (1958 p.45). He reviewed the important aspects of customer focus movement and carefully related them to education. He was of the opinion that there should be a partnership between the government and the education system in order to improve education. He stressed on the importance of students being treated as customers, their importance in the whole system and the quality of education offered to them being based on the requirements of the jobs the students seek after graduating. Deming argues that consumer research should be done every one in a while and findings used to consider the most important strategies in implementing quality and customer focus movements, with the belief that appropriate responses to customer needs can go a long way in guaranteeing customer satisfaction. Feedback from customers should be the basis upon which teachers can achieve their educational goals where students are concerned, while at the same time increasing their own job satisfaction.

A research study carried out by one Coulson (1996 p.57) showed that teachers have a positive attitude towards the concept of customer focus, and this would form a good basis on which to start the implementation of customer focus. Despite the increased levels of awareness among teachers, parents, students and community leaders are still critical of the quality of university education.

The implementation process of customer focus is as simple as having the customer in mind in all levels of policy and decision making as well as incorporating them in the simple day to day activities that are rather taken for granted or as obvious. Some of the steps that would make the implementation process as easy as it sounds are;

Encouraging face to face dealings

According to Adrian Thompson 2010 in his article ‘Customer Satisfaction in 7 steps,’ face to face dealings is the most crucial part of interacting with a customer. However, he acknowledges that it is not always easy to have a one-on-one interaction with clients at all times. However, in his findings, Adrian discovered that customers find it easier to work with a person they have met in person, rather than one they have only spoken to over the phone or communicated with over the internet. Face to face dealings provide one with opportunity to know their customer in person and to take time to understand what it is that the customer really needs since feedback is instant.

Responding to messages promptly and keeping clients informed

We all know that it is quite annoying to keep waiting for a response for days on end. When it comes to customers, nothing annoys them more than to be denied immediate feedback, especially to information considered really important. Even though dealing with customers queries within few hours may not always be possible, but it is always advisable to at least call back or send an email and let the customer know that their concern has been received and is being worked on. Even if the customer may not receive a response right away, it is only fair to let them know that their request is being worked on. This way, the customer is likely to stick with you and not move their business elsewhere (Arthur and Carrie, 2009, p.76).

Being friendly and approachable

Have you ever considered the truth in the saying that one can hear a smile through the phone? It is very important to be friendly and courteous, even to customers who cannot see you physically. Make them feel that you are there to help them out and to respond to their needs accordingly. Always keep a clear head and respond to your clients’ needs to the best of your ability as politely and courteously as possible (Schmoker and Wilson 1993, p.46).

Having a clearly defined customer service policy

In the universities, having policies that are well formulated on the services that are offered to students and what course of action the customer (student) can take in case the quality and standards are not met is very crucial. This goes a long way in helping the students realize that their interests are held dearly and safeguarded and that they can always achieve the best they want to. This is especially in regard to library stock, quality of lecture notes and grading of assignments. Policies should also clearly define what happens in case the first course of action taken does not work, and they should not merely be policies, but must be felt to work practically (William, 1996, p.113).

Honouring promises

Customers hate to be disappointed and so when a business or organization promises something, it should honour that promise and be sure to deliver. In the case of universities for example, suppose the promise to upgrade the library stock, or increase the number of lecture hours for a given discipline, they should see to it that this is done within the shortest time possible and if not, the students (customers) should be updated on an ongoing basis on the progress being made

Customer orientation is a business approach in which a company solves for the customer first. It's all about focusing on helping customers meet their goals. Essentially, the needs and wants of the customer are valued over the needs of the business. For customer service, this means your support team is focused on meeting customer needs.

Rather than implementing a customer orientation approach, some companies choose to use a sales orientation methodology. This means that your business would value the needs and wants of the company over the customer.

The sales orientation approach doesn't align well with the inbound methodology. With inbound customer service, your support team is focused on providing helpful, human, and holistic solutions to your customers.

That's why approaching business from a customer orientation works well with an inbound philosophy.

A customer orientation approach is useful for several reasons. For one, as mentioned above, it's more cost-effective to retain customers than it is to acquire new ones.

Additionally, the happier your customers are, the more likely they are to become ambassadors for your brand.

For example, when you calculate Net Promoter Score, you're hoping to have as many promoters as possible. Promoters are loyal to your brand and will tell their friends about it.

Plus, in this day and age, customers know what they want. They're highly knowledgeable and have more resources than ever before

How To Implement Customer Orientation

1. Recruit the right people.

Who you hire is of the utmost importance for your customer service team? Instead of hiring for skills, which you can teach, hire for attitude and friendliness. Plus, look for empathetic people who can problem solve. Finding the right people can make or break a customer support team.

2. Value your employees.

Customer support can often be a thankless job. But it shouldn't be. Don't forget to treat your employees well. If they're happy coming to work, it makes it easier for them to focus on the customers.

3. Provide excellent training.

Your entire team needs to be trained on the customer first approach. In regards to customer support, training should focus on product knowledge, troubleshooting, and customer care.

4. Lead by example.

The entire leadership and management team needs to fully embrace a customer orientation approach. If they don't, your team won't feel comfortable to implement this strategy. For example, you can't punish employees for solving for the customer. This means that the company culture needs to follow through on what you say your values are. For instance, support staff shouldn't get punished for making product suggestions.

5. Understand the customer.

It's important to understand your customer. For customer support, this means empathizing with customers who are upset. Listen to them. It's important that your customer support team truly understands your customer’s needs.

6. Iterate your process.

Keep in mind that your customers' needs are always changing and evolving over time. Your company should evolve and change with them. With a customer orientation approach, your business should always be focused on figuring out how you can accommodate changing needs, and hopefully anticipate them.

7. Empower your staff.

Your customer support team should have the authority to resolve most customer complaints. Plus, your support staff should be empowered to suggest changes to management that would benefit customers in the long run.

8. Receive feedback.

Since customer needs are always changing, you'll have to talk to your customers about what they need and want. Customer support is in a unique position to do this. Your customer support team will have a pulse on what customers are upset about and what changes can be made.

Customer satisfaction-

It refers to the measure of how products and defined as the number of customers, or percentage of total customers, whose reported experience with a firm, its products, or its services (ratings) exceeds specified satisfaction goals.

It is seen as a key performance indicator within business and is often part of a Balanced Scorecard. In a competitive marketplace where businesses compete for customers, customer satisfaction is seen as a key differentiator and increasingly has become a key element of business strategy.

Within organizations, customer satisfaction ratings can have powerful effects. They focus employees on the importance of fulfilling customers’ expectations. Furthermore, when these ratings dip, they warn of problems that can affect sales and profitability. When a brand has loyal customers, it gains positive word-of-mouth marketing, which is both free and highly effective.

Therefore, it is essential for businesses to effectively manage customer satisfaction. To be able do this, firms need reliable and representative measures of satisfaction.

In researching satisfaction, firms generally ask customers whether their product or service has met or exceeded expectations. Thus, expectations are a key factor behind satisfaction. When customers have high expectations and the reality falls short, they will be disappointed and will likely rate their experience as less than satisfying.

CUSTOMER SATISFACTION METHODS

1. Encouraging Face-to-Face Dealings with customers.

This is the most daunting and downright scary part of interacting with a customer. If you’re not used to this sort of thing it can be a pretty nerve-wracking experience. Rest assured, though, it does get easier over time. It’s important to meet the customers face to face at least once or even twice during the course of a project.

In doing so, the client finds it easier to relate to and work with someone they’ve actually met in person, rather than a voice on the phone or someone typing into an email or messenger program. When you do meet them, be calm, confident and above all, take time to ask them what they need.

2. Respond to Messages Promptly & Keep the Clients Informed

This goes without saying really. We all know how annoying it is to wait days for a response to an email or phone call. It might not always be practical to deal with all customers’ queries within the space of a few hours, but at least email or call them back and let them know you’ve received their message and you’ll contact them about it as soon as possible. Even if you’re not able to solve a problem right away, let the customer know you’re working on it.

3. Being friendly and approachable by customers.

It’s very important to be friendly, courteous and to make your clients feel like you’re their friend and you’re there to help them out. There will be times when you want to beat your clients over the head repeatedly with a blunt object – it happens to all of us. It’s vital that you keep a clear head, respond to your clients’ wishes as best you can, and at all times remain polite and courteous.

4. Have a Clearly-Defined Customer Service Policy

This may not be too important when you’re just starting out, but a clearly defined customer service policy is going to save a lot of time and effort in the long run. If a customer has a problem, what should they do? If the first option doesn’t work, then what? Should they contact different people for billing and technical enquiries? If they’re not satisfied with any aspect of your customer service, who should they tell?

Customer Complaints/Feedback should be continuously solicited as customer preferences keep on changing. Let us remember those days when the original red Lifebuoy was selling like hot cake. Now people’s preferences have changed. The organization has come up with many variations of Lifebuoy. The basic USP remains the same, ‘health and hygiene’ but concepts of, beauty and healthy skin is thrown in to satisfy the changed customer needs.

Purpose of Feedback:

Discover Customer Dissatisfaction: The feedback helps to know how satisfied or dissatisfied the customer is. A customer who does not complain and switches to another brand is more dangerous than a customer who complains. Customer dissatisfaction can be a big eye opener and help discover what more needs to be done for a product or service.

Discover Relative Priorities of Quality: Certain parameters of quality are more important than others. Whenever planning for a quality goal, the organization should prioritize its goals.

Compare Performance with Competition: Watching competitor activity is a good learning tool for any organization. This is a way of benchmarking us vis-à-vis others.

Identify Customer’s Needs: There is a saying that salesman who discovers a customer need before everyone else is more likely to get the sales. The same logic holds for organizations as well. You can always reap the benefits of first mover advantage. Let us take example of Frooti. Probably Frooti is the first brand to identify the Indian taste and to make an effort to cater to that taste. No matter how many drinks with mango flavour has come Frooti remains the numero uno in its segment.

Determine Opportunities for Improvement: Customer feedback also helps an organization in determining about opportunities for improvement.

Customer Retention-

It means “retaining the customer” to support the business. It is more powerful and effective than customer satisfaction.

For Customer Retention, we need to have both “Customer satisfaction & Customer loyalty”.

The following steps are important for customer retention.

1. Top management commitment to the customer satisfaction.

2. Identify and understand the customers what they like and dislike about the organization.

3. Develop standards of quality service and performance.

4. Recruit, train and reward good staff.

5. Always stay in touch with customer.

6. Work towards continuous improvement of customer service and customer retention.

7. Reward service accomplishments by the front-line staff.

8. Customer Retention moves customer satisfaction to the next level by determining what is truly important to the customers.

9. Customer satisfaction is the connection between customer satisfaction and bottom line.

Cost of quality (COQ) is defined as a methodology that allows an organization to determine the extent to which its resources are used for activities that prevent poor quality, that appraise the quality of the organization’s products or services, and that result from internal and external failures. Having such information allows an organization to determine the potential savings to be gained by implementing process improvements.

- Cost of poor quality (COPQ)

- Appraisal costs

- Internal failure costs

- External failure costs

- Prevention costs

- COQ and organizational objectives

- COQ resources

WHAT IS COST OF POOR QUALITY (COPQ)?

Cost of poor quality (COPQ) is defined as the costs associated with providing poor quality products or services. There are three categories:

- Appraisal costs are costs incurred to determine the degree of conformance to quality requirements.

- Internal failure costs are costs associated with defects found before the customer receives the product or service.

- External failure costs are costs associated with defects found after the customer receives the product or service.

Quality-related activities that incur costs may be divided into prevention costs, appraisal costs, and internal and external failure costs.

Appraisal costs

Appraisal costs are associated with measuring and monitoring activities related to quality. These costs are associated with the suppliers’ and customers’ evaluation of purchased materials, processes, products, and services to ensure that they conform to specifications. They could include:

- Verification: Checking of incoming material, process setup, and products against agreed specifications

- Quality audits: Confirmation that the quality system is functioning correctly

- Supplier rating: Assessment and approval of suppliers of products and services

Internal failure costs

Internal failure costs are incurred to remedy defects discovered before the product or service is delivered to the customer. These costs occur when the results of work fail to reach design quality standards and are detected before they are transferred to the customer. They could include:

- Waste: Performance of unnecessary work or holding of stock as a result of errors, poor organization, or communication

- Scrap: Defective product or material that cannot be repaired, used, or sold

- Rework or rectification: Correction of defective material or errors

- Failure analysis: Activity required to establish the causes of internal product or service failure

External failure costs

External failure costs are incurred to remedy defects discovered by customers. These costs occur when products or services that fail to reach design quality standards are not detected until after transfer to the customer. They could include:

- Repairs and servicing: Of both returned products and those in the field

- Warranty claims: Failed products that are replaced or services that are re-performed under a guarantee

- Complaints: All work and costs associated with handling and servicing customers’ complaints

- Returns: Handling and investigation of rejected or recalled products, including transport costs

PREVENTION COSTS

Prevention costs are incurred to prevent or avoid quality problems. These costs are associated with the design, implementation, and maintenance of the quality management system. They are planned and incurred before actual operation, and they could include:

- Product or service requirements: Establishment of specifications for incoming materials, processes, finished products, and services

- Quality planning: Creation of plans for quality, reliability, operations, production, and inspection

- Quality assurance: Creation and maintenance of the quality system

- Training: Development, preparation, and maintenance of programs

COST OF QUALITY AND ORGANIZATIONAL OBJECTIVES

The costs of doing a quality job, conducting quality improvements, and achieving goals must be carefully managed so that the long-term effect of quality on the organization is a desirable one.

These costs must be a true measure of the quality effort, and they are best determined from an analysis of the costs of quality. Such an analysis provides a method of assessing the effectiveness of the management of quality and a means of determining problem areas, opportunities, savings, and action priorities.

Cost of quality is also an important communication tool. Philip Crosby demonstrated what a powerful tool it could be to raise awareness of the importance of quality. He referred to the measure as the "price of nonconformance" and argued that organizations choose to pay for poor quality.

Many organizations will have true quality-related costs as high as 15-20% of sales revenue, some going as high as 40% of total operations. A general rule of thumb is that costs of poor quality in a thriving company will be about 10-15% of operations. Effective quality improvement programs can reduce this substantially, thus making a direct contribution to profits.

The quality cost system, once established, should become dynamic and have a positive impact on the achievement of the organization’s mission, goals, and objectives.

Cost of Quality Example

COST OF QUALITY RESOURCES

You can also search articles, case studies, and publications for cost of quality resources.

Using Cost of Quality to Improve Business Results (PDF) Since centering improvement efforts on cost of quality, CRC Industries has reduced failure dollars as a percentage of sales and saved hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Cost of Quality: Why More Organizations Do Not Use It Effectively (World Conference on Quality and Improvement) Quality managers in organizations that do not track cost of quality cite as reasons a lack of management support for quality control, time and cost of COQ tracking, lack of knowledge of how to track data, and lack of basic cost data.

The Tip of the Iceberg (Quality Progress) A Six Sigma initiative focused on reducing the costs of poor quality enables management to reap increased customer satisfaction and bottom-line results.

Cost of Quality (COQ): Which Collection System Should Be Used? (World Conference on Quality and Improvement) This article identifies the various COQ systems available and the benefits and disadvantages of using each system.

References:

1. Course Notes - National Institute of Technology, Calicut

2. Production and Operation Management - DDCE Utkal University