UNIT III

Theories Of Wages, Interest And Employment

Introduction:

The term "wages" is defined as the sum of money paid by the employer under the contract to the worker for the rendered services. Wage payment is essentially the price paid for a particular commodity, IE., Labour service. According to the classical theory of wages, labour supply was considered a function of real wages. But according to Keynes, workers irrationally and generally negotiated for money wages, and they reacted sharply against the reduction of money wages. Monetary wages are also called nominal wages. But money wages alone may not give the right idea of what workers really earn; it will determine the standard of living of workers.

Factors that determine real wages:

The factors that determine the real wage or standard of living of workers are:

(a) The purchasing power of money: the purchasing power of money is used to compare wages in different places and at different times. It is reversed by the price level, that is, the higher the price, the lower the purchasing power and vice versa. Part of the high wages in the UK and North America may be due to the prevailing price increases in those countries/regions.

(b) Subsidiary income: Subsidiary income is the income that an employee has in the form of money or goods, in addition to normal money wages. For example, free boards and accommodation are provided to household servants and peons, professors who earn additional income by marking exam papers, etc.

(c) Extra work without extra pay: If an employee needs to do extra work without compensation, his real wage will be reduced to that extent.

(d) Regularity or irregularity of employment: Regular or safer employment may be given a wage of money, but its actual income may be given a wage of higher money.

(e) Conditions of work: Some professions are healthier than others, and some work hours are shorter than others. All these things are taken into account in the assessment of real wages.

(f) Future prospects: if there is a good prospect of rising in the future, a low money income is considered a high real wage.

Theory of wages:

(A) Subsistence theory:

This theory originated from the Physics School of French economists and was developed by Adam Smith and later economists of the classical school. The German economist Lassar used to call it the Iron Law of wages or the brazen law of wages. Karl Marx made it the basis of his theory of exploitation.

According to this theory, wages tend to settle at a level sufficient to keep workers and their families at a subsistence level. When wages exceed the self-sufficiency level, workers are encouraged to marry and have large families. The mass supply of Labour reduces wages to the level of self-sufficiency. If wages fall below this level, marriage and childbirth will be discouraged, and lack of nutrition will increase mortality. Eventually, the labour supply will decrease until wages rise again to the self-sufficiency level. It is believed that the supply of Labour is infinitely elastic, that is, as the price offered (that is, wages) increases, its supply increases.

Criticism:

This theory is almost completely obsolete, and there is no such practical application, especially in developed countries. This theory was based on the Malthus theory of the population. It would be inappropriate to say that with each increase in wages, the rise in the birth rate must necessarily continue. Higher living standards may follow, followed by higher wages.

- Ricardo was one of the indices of subsistence theory. He emphasized the influence of habits and habits in determining what workers need. But habits and habits change over time. Therefore, the theory cannot hold good for a longer period, especially in a world characterized by rapidly changing habits. Therefore, Ricardo acknowledged that in an improving society, wages could exceed the self-sufficiency level indefinitely.

- The second criticism of this theory is that the self-sufficiency level is more or less uniform for all working classes, with certain exceptions. Therefore, theory does not explain the difference in wages in different jobs.

- The third criticism is that this theory explains wages only with reference to supply, and the demand side is completely ignored. On the demand side, the employer must take into account the amount of work that the employee gives, not the self-sufficiency of the worker.

- The fourth criticism is that the theory does not account for wage adjustments over the lifetime of generations and for wage fluctuations from year to year.

- The fifth and final criticism is that the term "subsistence" has a very vague impression. Does it refer to the minimum requirements of modern man or tribal Barbarians?

(b) Wage fund theory:

This theory is based on J. S. Associated with the name of the mill. According to wage fund theory, wages depend on two amounts, IE.:

- Circulating capital reserved for the purchase of wage funds or labour; and

- The number of workers seeking employment.

Since this theory takes the wage fund as a fixed, wages can only rise due to a decrease in the number of workers. It said efforts by unions to raise wages were futile. If they succeed in raising wages in one trade, then the wage fund is fixed, and the trade union does not control the population, so at the expense of another trade, therefore, according to this theory, the trade union cannot raise wages for the entire working class.

Criticism:

This theory has been widely criticized and is now rejected. J.S.Even mill himself recited it in the second edition of his book" Principles of political economy". Mill thought that wages would be paid only from Circular capital. Whether the source of wages is capital or current products has been the subject of intense debate in the past. The fact is that if the production process is short (for example, the final stage of the production process), wages may be paid from the current production. On the other hand, if the production process is long, workers obviously do not get wages from the products of labour directly or through replacement. In such cases, wages mostly come out of the capital. This theory cannot be applied in advanced developed countries, but it can be applied in developed countries suffering from capital shortages, and wages cannot be raised unless capital is accumulated by increasing national income and industrialization.

(c) Residual claimant theory:

The residual claimant theory is advanced by the American economist Walker. According to Walker, wages are the residue left after other facts of production are paid. According to Walker, rent and interest are governed by contracts, but profits are determined by clear principles. There is no similar principle with respect to wages.

The theory acknowledges the possibility of higher wages by increasing the efficiency of employees. In this sense, it was an optimistic theory, and the self-sufficiency theory and the wage fund theory were pessimistic theories. Although this theory is too rejected by most economists on several grounds.

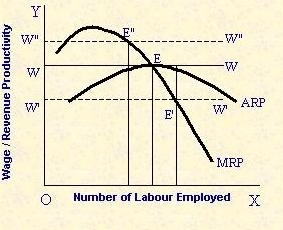

(d) The Theory of marginal productivity wages:

This theory states that under the conditions of perfect competition, all workers with the same skills and efficiency in a given category receive wages equal to the value of the marginal product of that type of Labour. The limit of labour in any industry products is the amount in which the production volume increases if the unit of labour increases, while the volume of other factors of production remains constant. Under full competition, the employer will continue to hire the worker until the value of the product of the last worker he hires is equal to the limit or the additional cost of hiring the last worker. In addition, under full competition, the marginal labour cost will always be equal to the wage rate, regardless of the number of workers the employer may engage in. All industries are subject to a decrease in returns, so the marginal products of Labour must sooner or later begin to decrease. Wages remain constant, and employers stop hiring more workers at a time when the value of the marginal product is equal to the wage rate: as assumed above, it is not true that the number of other factors remains constant, and the amount of labour alone increases. To make this possible, the term" marginal net product of Labour" is used instead of" marginal product of Labour". The value of a marginal net product of Labour can be defined as the value of an amount in which the output increases by hiring another worker with the appropriate addition of other factors, less than the addition to the cost of other factors caused by increasing the amount of other factors.

Fig 1

Limits/criticisms of marginal productivity theory:

This theory is true only under certain assumptions such as perfect competition, complete mobility of Labour, homogeneous character of all labour, constant interest and rent, given price of products, etc. It's a static theory. The real world is dynamic. All assumptions are unrealistic. Criticism of this theory is as follows:

- According to this theory, labour is fully mobile and can move from one employment to another, but this is not true in the real world.

- According to this theory, there is a uniform wage rate throughout the market, which is impossible. Workers with the same skills and efficiency cannot receive the same pay in two different locations.

- In the case of monophony, i.e., one buyer and many sellers, the employer has a grip on wages and can pull down wages below the value of the marginal net product of Labour. If the employees are collectively organized, then the wage rate can be negotiated. Thus, wages are determined not only by the number of employed workers, but also by the relative bargaining power of the Union and the employer.

- Another assumption of this theory is that there is a perfect competitive market existence for the product, which is also an unrealistic assumption. In the real world, the market of goods is characterized by incomplete competition. This also destabilizes the theory.

- It should be noted that the marginal net product of Labour depends not only on the supply of labour, but also on the supply of all other production factors. If other factors are abundant and labour is relatively small, then the marginal product of Labour is higher, and vice versa.

- This theory regards the supply of labour as the norm. Productivity is also a function of wages. Low productivity can be a source of low wages that can signal workers ' efficiency, lower living standards and ultimately check the supply of Labour.

(e) Wages theory of Tausig’s:

He gave new version of version of the marginal productivity theory of wages. According to him, wages represent marginal discount products of Labour. According to Tausig, workers cannot get the full amount of marginal production. This is due to the fact that production takes time and you cannot get the final product of Labour immediately. But workers must be supported in the meantime. This is done by capitalist employers. The employer does not pay the full amount of the expected limit product of Labour. He subtracts a certain percentage from the final output to compensate himself for the risks he takes when making an advance payment. According to Tausig, this deduction is made at the current rate of interest.

Criticism:

- A dim and abstract theory remote from real problems. To this, he answers that this weakness is common to all economic generalizations.

- Joint goods are discounted at the current rate of interest, but according to his own analysis, the rate of interest is the result of the process of progress to the worker.

- To meet this difficulty, Tausig suggests that the time preference rate determines the rate of interest independently of marginal productivity, and the rate of interest determines the marginal product discount of Labour.

- This theory is also rejected by most economists.

Modern wage theory:

According to this theory, wages are determined by the interaction of supply and demand, as in the case of ordinary goods. Therefore, this theory is also called the theory of supply and demand.

Labour demand: According to modern wage theory, labour demand partly reflects the productivity of workers and partly the market value of products at different levels of production. The factors that determine the demand for labour are:

a) Derivative demand: demand for Labour is derivative demand. It is derived from the demand for goods that it helps to produce. The greater the consumer demands for the product, the greater the producer's demand for the labour required to produce the goods. It may be observed that it is the expected demand, and not the existing demand for the product that determines the demand for Labour. Therefore, the expected increase in demand for products will increase the demand for Labour.

b) Elasticity of labour demand: the elasticity of labour demand depends on the elasticity of commodity demand. According to this theory, if wages are formed only a small percentage of total wages, then the demand for labour become generally inelastic. On the other hand, if the demand for the product is also elastic, or if cheaper alternatives are available, then the demand will be elastic.

c) Price & quantity of cooperating factors: the demand for Labour also depends on the price and quantity of cooperating factors. If the machine is expensive, then the demand for Labour will increase. The greater the demand for cooperative factors, the greater the demand for labor, and vice versa

d) Technical progress: Another factor affecting labor demand is technological progress. In some cases, Labor and machineries are used in clear proportion

After considering all the relevant factors as described above, the employer is governed by one basic factor-viz., Marginal productivity. The change in the wage rate determines the direction of changes in labour demand, but the degree of this change depends on the elasticity of labour demand. In the case of elastic demand, a slight change in the wage rate leads to a significant change in labour demand, and vice versa. Whether labour demand is resilient depends on

(i) The technical conditions of production and

(ii) The elasticity of demand for the goods that labour produces. In general, short-term demand for Labour is less resilient than long-term demand. That is why employers and unions have adopted a rigid attitude in wage negotiations.

Labor demand under full competition: under full competition, each enterprise constitutes a very small part of the entire industry, and the supply curve of labour faced by each employer on wages by employing more or less labour is completely elastic, that is, a horizontal straight line at the level of the market wage rate. Individual employers not only equate the marginal productivity of labor with the wage rate of the mark, but also employ many workers

Fig 2

It is the demand of the entire industry, not individual companies, which determines the wage rate. Individual companies must accept the market rate of wages and adjust their own demand for labour accordingly.

Supply of labour:

The supply of labour depends as follows:

1) the number of workers of a certain type of labor that provide themselves for employment at different wage rates; and

2) the number of hours per day or the number of days per week when they are ready to work,

Labour can supply three destinations:

- Labor supply to enterprises: For a particular enterprise, at the current wage rate, the labor supply is completely elastic because it can engage as many workers as you want. Its own demand is only a very small part of the total supply of Labor. Thus, the labor supply curve of the enterprise is a vertical straight line.

2. Labor supply to industry: For the industry as a whole, the supply of Labor is not infinitely elastic. If the industry wants more labor, it will attract the industry by providing high wages. Labor supply to industry is subject to the supply law, that is, the supply law. The supply varies directly with the price, which means a small supply of low wages and a large supply of high wages. Thus, the supply curve of labor for industry is tilted upward from left to right.

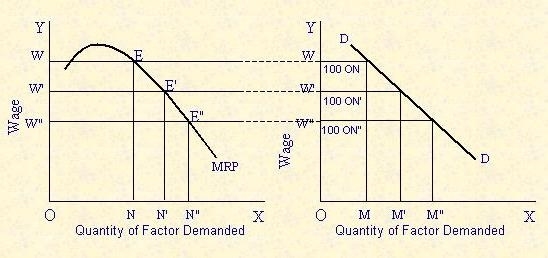

3. Labor supply to the economy: The supply of labor for the entire economy depends on economic, social and political factors or institutional factors, for example, the attitude of women to work, the working age, the age of school or university and the possibility of part-time employment for students, the size and composition of the population and gender distribution, the attitude to marriage, the size of the family, contraception, etc. Over a short period of time, the reduction in wages may not cause any decrease in the supply of Labor. But if wages are too low, competition among employers themselves will push them up. Even over a long period of time, the supply of Labor is not very elastic. A certain minimum wage, where Labor does not work at all, is below. If this minimum is exceeded, the supply of labor increases as the wage rate increases. But this only happens to the point when the increase in wages leads to a decrease in the supply of Labor. Again, after the point, this trend will be reversed if we consider that workers can move on to a higher level of life. Thus, an increase in wages can lead to an increase or decrease in the supply of Labor. It depends on the relative assessment of the goods and leisure of the worker.

Thus, the supply of Labor depends on the elasticity of demand for income, which varies depending on the temperament of the worker and the social environment. When the standard of living of workers is low, they may be able to fulfil their wishes with a small income, and when they make it, they may prefer leisure to work. That is why it happens that sometimes an increase in wages leads to a contraction in the supply of Labor. It is represented by the backward bending supply curve of labor, as shown in the following figure:

Fig 3

For a while, this particular individual is ready to work longer hours as wages rise (wages are represented by the OY axis). But beyond wages, he would reduce rather than increase working hours.

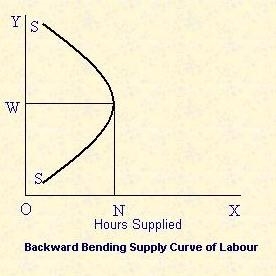

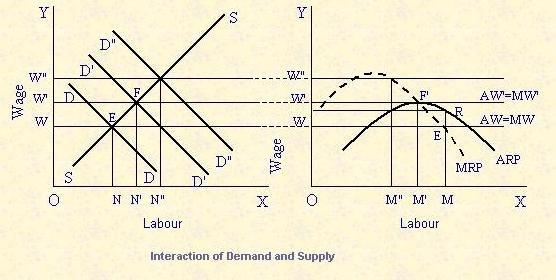

Interaction between supply and demand:

Fig 4

In the figure above,

(a) It represents the supply curve facing the industry, and

(b) Figure (b) represents the supply curve facing individual companies. W-AW is an extension line that cuts the corporate MRP (marginal revenue productivity) curve in Figure (b) E'. At this level, the ARP (average earnings productivity) is MR greater than the wage OW in Figure (b). Therefore, every company (since this company represents all companies in the industry) has a super-regular profit at this level of wages. This will lead to the entry of new companies into the industry; labor demand will increase and wage levels will rise. Therefore, ultra-regular profits will be competed by the entry of new companies in the long run.

New demand curve D'd'd cut figure (a) supply curve SS at Point F. The wage level in this situation will be OW higher than the original wage level OW. This is how the interaction of supply and demand determines wages. When wages are OW, the company is in equilibrium at e' and when wages go up at OW', the equilibrium is F'. At this point, the average income productivity (ARP) and marginal income productivity (MRP) are equal, and the average wage OW is both equal.

It also happens that the occurrence of ultra-regular profit attracts some companies from the outside, which can further increase the demand for Labor to d"D". Then the wage level will be OW". Here, ARP is less than wage OW", that is, companies are suffering losses. The result is that some companies will leave the industry and wages will fall to the level of OW.

Long-term:

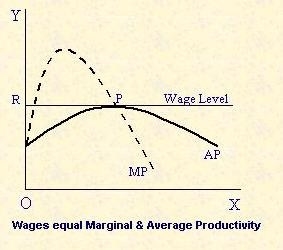

Under perfect competition, wages, in the long run, are equal to marginal values as well as the average productivity of Labor. If marginal productivity is greater than average, it will be worthwhile to adopt more labor until marginal productivity falls to the level of average productivity. On the other hand, if the marginal productivity is less than the average productivity, there will be less labor, and the marginal productivity will rise to the level of average productivity. Marginal and average productivity tend to be equalized this way. Since wages are equal to marginal productivity, in the long run they are also equal to average productivity. This is shown in the following figure:

Fig 5

Or wage level, where AP is the average productivity curve, and MP is the marginal productivity curve. They are crossed by p, indicating that wages are equal to both MP and AP. When AP is standing, MP>AP, and when the AP is standing, MP<AP. But when the AP is neither rising nor falling, MP=AP. So, at the equilibrium point, wage = MP=AP.

Wages under incomplete competition:

Incomplete competition may arise:

(A) Bilateral monopoly: When strong employer associations are faced with strong labor organizations.

(b) Monophony: when an industrial employer or a group of employers occupies a very strong monopoly position in comparison with Labor.

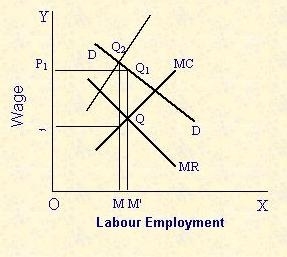

(a) Bilateral monopoly: the term “bilateral monopoly “applies to both goods and labor. This applies to situations where the monopoly of purchases coincides with the monopoly of sales, that is, a single monopoly facing a single monopolist. Monopolies want to operate on a scale where marginal costs are equal to marginal revenues. Monopolists, on the other hand, want to buy an amount whose marginal cost is equal to marginal utility. This indicates the best price for the buyer and the best price for the seller. There is no economic principle for determining equilibrium prices.

It definitely can't show the output and the price to dominate. The price depends on the circumstances of each case. In some cases, it can be a compromise price that can be affected by the negotiating power of each party. Therefore, under bilateral monopolies, prices and output are "indeterminate".

Fig 6

In bilateral monopoly, each side wants to get the other better through negotiation skills. A monopolist likes to behave as if the monopolist is one of many buyers in a perfect competition, so he (i.e. the buyer) can accept the price fixed by the company (the monopolist producer). Similarly, a monopolist would prefer to behave as if a monopolist is a perfect competitive producer (i.e., one of so many) who cannot influence the price. Now we cannot say who will succeed and how much. Perhaps there will be a compromise between the two extremes.

According to the figure above, if you sell the output of Om and charge the price of OP1 (M'q), then Q1 is the point of the demand curve DD indicating that the buyer is willing to pay under full competition, so the monopolist will maximize the profit (MR=MC). On the other hand, Q2, where DD and MC1 intersect, is the point where the buyer's marginal rating is equal to the marginal purchase cost, so monopolists would like to buy OM at the OP price. There is a compromise between the parties, that is, between the employer and the employee. So the price of the factor will be somewhere between OP and OP1, depending on the relative negotiating skills of the parties, and the output between OM and OM'.

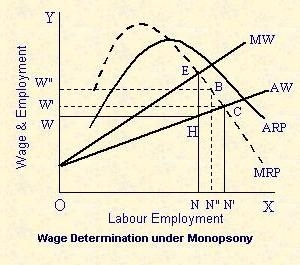

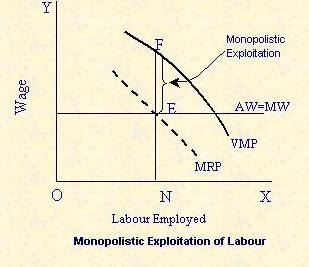

(b) Monophony: whereas Labor occupies a very weak position in comparison, this is the most common situation of incomplete competition in which the employer embodies the concentrated monopoly power of being the sole purchaser of labor in his person. Monophony also wants to ensure that big employers are in a position to influence wages. In the following illustration shows a situation where monopolists abuse labor:

Fig 7

In the figure above, MRP is the marginal revenue productivity curve representing labor demand. The supply curve of Labor is AW (average wage curve), which indicates that higher wages must be paid to engage more labor. MW is the marginal wage curve corresponding to the AW curve. These two curves, namely the MW curve and the MRP curve, intersect at the point E. Here, the marginal wage is equal to the marginal income productivity of labor at the level of labor employment at the wage level NH (=OW)

It means that individual companies are earning normal profits.

Exploitation of labour:

There are three types of labour exploitation:

(a) Monophonic exploitation: where a single employer has the strongest impact on wage rates.

(b) Exclusive exploitation: in this state, there is complete competition in the labour market, but incomplete competition in the product market. In equilibrium, the company equates wages with marginal revenue products. This means that labour is paid less than the value of marginal products, which indicate exploitation.

Fig 9

(c) Double exploitation: occurs when there is incomplete competition in both the labour market (monophony) and the product market (monopoly). Thus, there is a double exploitation of unitary and monopolistic labour, in which labour is most exploited.

Remedies:

Follow remedies or weapons to stop labour exploitation

- Government intervention, and

- Trade union action.

Wage gap:

Everywhere wages tend to approximate the marginal productivity of labour. However, the marginal productivity of labour depends on employment and grade. It depends on the degree of scarcity of labour of each kind in connection with the demand for it.

The causes of differences in wages in different jobs, professions and regions are as follows:

- Difference in efficiency: that is, the difference in the conditions under which education, training and work are performed

B. The presence of non-competing groups: these groups arise due to difficulties in the way of the movement of labour. We can see that this wage, or NH, is less than the marginal income productivity, which is NE. So each worker gets EH less than this marginal income product. This is a measure of labour exploitation under monophony. This is called “monopsonic exploitation” by Mrs Robinson. Thus, under monophony, wages are lower, and employment is less than under full competition in the labour market. Under perfect competition, the equilibrium would have been C where the supply curve AW cuts the demand curve MRP. At this point, wages would have been higher in OW'(=N'C) and the labour employed would have been greater in ON’. From low-wage to high-wage employments. Following are the reasons:

C. Difficulty in learning Trade: few people can master difficult trade. Their supply is less than their demand, and their wages are higher.

D. Differences in comfort or social respect: disgusting employment must pay higher wages to attract workers. If a disgusting job is done by unskilled workers who cannot do anything better, wages can be quite low, for example, a sweeper.

E. future prospects: if a profession provides an opportunity for future promotion, people will accept a low star in it, as well as another profession offering a higher initial reward, but will not be able to do so.、

F. Dangerous and dangerous occupation: Generally, offers higher emoluments.

G. Regularity or irregularity of employment: It also has a strong effect on the level of wages.

H. Collective Bargaining: Differences in the strength and militancy of trade unions also explain differences in wages in different industries.

Introduction:

The outline of this theory can be expressed as follows. As employment increases, total real income increases. The psychology of the community is such that when total real income increases, total consumption increases, but not as much as income. If the totality of increased employment is to be dedicated to meeting the increased demand for immediate consumption, therefore employers will make a loss. Thus, to justify any amount of employment, unless this amount of total investment exceeds what the community chooses to consume when employment is at a given level, the entrepreneur's receipt will be less than is required to induce them to provide a given amount of employment. Thus, given what we call the consumption trend of the community, the equilibrium level of employment, that is, the level at which there is no induction to the employer as a whole, either to expand employment or to contract employment, depends on the current amount of investment. The current investment amount, in turn, depends on what we call investment induction, and it can be seen that investment induction depends on the relationship between the schedule of capital's marginal efficiency and the complexity of lending rates for various maturities and risks.

Therefore, given the consumption trend and the new investment rate, there is only one level of employment that is consistent with the equilibrium, while the other level leads to inequality between the total supply price of output as a whole and its aggregate demand price. This level cannot be greater than full employment. But there's generally no reason to expect it to equal full employment. Effective demand associated with full employment is a special case, it is realized only when the consumption trend and investment induction are in a certain relationship with each other. This particular relation, corresponding to the assumptions of classical theory, is in a sense an optimal relation. But it can only exist when, by chance or by design, the current investment provides an amount of demand equal to the excess of the total supply price of output resulting from full employment than what the community chooses to spend on consumption when fully employed.

This theory can be summarized in the following proposition:

(1) In a given situation of technology, resources and costs, income (both monetary and real income) depends on the amount of Employment N.

(2) the relationship between the income of the community and what can be expected to be spent on the consumption specified by D1 depends on the psychological characteristics of the community, which is to say, consumption depends on the level of gross income, and therefore on the level of Employment N, unless there is some change in the consumption trend.

(3) The amount of labour that an entrepreneur decides to hire N depends on the sum of D1, which is the amount that the community is expected to spend on consumption, and D2, which is the amount that it is expected to spend on new investments. D is what we called above effective demand.

(4) D1+D2=D=σ(N), where σ is the aggregate supply function, and as seen in(2)above, D1 is a function of n, and we can write σ(N) depending on the consumption trend, so σ(N)-σ(N)=D2.

(5) thus, the amount of employment in equilibrium depends on(i)the total supply function σ, (ii)the consumption trend σ, and(iii) the amount D2 of investment.

(6) For all values of n, there is the corresponding marginal productivity of labour in the wage property business, and it is this that determines the real wage. Thus, (5) is subject to the condition that n cannot exceed the value that reduces real wages equally to the marginal disadvantage of labour. This means that all changes in d are incompatible with the temporary assumption that money-wages are constant. Thus, eliminating this assumption is essential for the full statement of our theory.

(7) in the classical theory, if D=σ(N) for all values of N, then the amount of employment is in a neutral equilibrium that is less than its maximum for all values of n, and the force of competition among entrepreneurs is expected to push it to this maximum. Only at this point, in the classical theory, a stable equilibrium can exist.

8. The key to our practical problems is in this psychological law. From this we can conclude that the larger the amount of employment, the gap between the total supply price (Z) of the corresponding output and the sum (D1) that entrepreneurs can expect to recoup from consumer spending.

Thus, the amount of employment is not determined by the marginal disadvantage of labour measured at real wages. Consumption trends and the proportion of new investments determine the amount of employment among them, and the amount of employment is uniquely related to the given level of real wages—not the reverse. If consumption trends and the rate of new investment led to a shortage of effective demand, the actual employment level will be below the supply of potentially available labour at the existing real wage, and the equilibrium real wage will be greater than the marginal disadvantage of the equilibrium level of employment.

This analysis provides us with an explanation of the paradox of poverty in the midst of abundance. The lack of effective demand inhibits the production process, despite the fact that the marginal product of labour still exceeds the marginal disadvantage of employment.

In addition, the richer the community is, the wider the gap between actual production and potential production tends to widen. For poor communities, which tend to consume much of their output, a very modest measure of investment would be enough to provide full employment. On the other hand, wealthy communities will have to discover many amplified opportunities for investment if the savings trend of wealthy members is compatible with the employment of poor members. If the investment induction is weak in a potentially wealthy community, the working of the principle of effective demand, despite its potential wealth, is forced to reduce its actual output until the surplus to its consumption is sufficiently reduced to correspond to the weakness of the investment induction. Not only is the marginal consumption trend weak in wealthy communities [6], but the accumulation of capital is already large, so the opportunity for further investment is less attractive unless the rate of interest falls quickly enough.

Therefore, the analysis of consumption trends, the definition of the marginal efficiency of capital, the theory of the rate of interest are the three main gaps in our existing knowledge and must be filled. However, we discover that money plays an integral role in the theory of interest rates, and we must try to unravel the unique characteristics of money that distinguish it from others.

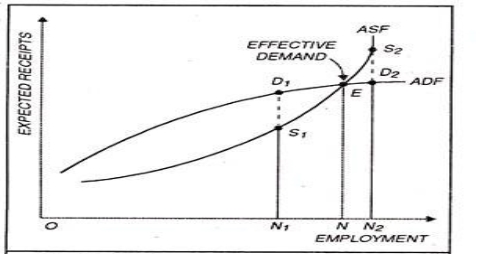

Theory of effective demand

Introduction to the Principle of Effective Demand

Before Keynes, no satisfactory explanation was given of the factors determining the level of employment in the economy. Economists mostly assumed the prevalence of the state of full employment by believing in Say's law of markets, an old proposition that states that all income is spent automatically or that the level of effective demand is always sufficient to lift all goods and services. Products from the market.

There were many economists who challenged the assumptions and logic of Say's Law. For example, T.R. Malthus endeavored to convince contemporaries that demand in general may not match supply in general and the shortage of aggregate demand could cause general overproduction and thus general unemployment. But Malthus failed to explain how actual demand could be lacking or excessive. It was Keynes who for the first time proposed a systematic and convincing theory of employment based on the "Principle of Effective Demand". The idea behind this theory is not difficult to grasp.

Keynes’s Principle of Effective Demand:

The principle of "effective demand" underlies Keynes's analysis of income, production and employment. Economic theory was radically changed with the introduction of this principle. In short, the effective demand principle tells us that in the short run, an economy's aggregate income and employment are determined by the level of aggregate demand that is satisfied by aggregate supply. Total employment depends on total demand. As employment increases, income increases. A fundamental principle of the propensity to consume is that as the real income of the community increases, consumption will also increase but less than income.

Therefore, to have enough demand to support an increase in employment, there must be an increase in real investment equal to the gap between income and consumption of that income. In other words, employment can only increase if investment increases. We can generalize and say; a certain level of income and employment can only be maintained if the investment is sufficient to absorb the savings of that level of income. This is the heart of the principle of effective demand.

Meaning of Effective Demand

Effective demand is manifested by the expenditure of income. It is judged by the total expenditure of the economy. The total demand of the economy consists of consumer goods and capital goods, although the demand for consumer goods constitutes a large part of the total demand. Consumption continues to increase with increasing income and employment. At different income levels, there are corresponding demand levels, but not all demand levels are effective. Only that level of demand is efficient which is fully satisfied with the coming supply, so that entrepreneurs do not tend to reduce or increase production.

Effective demand is the demand for production as a whole; in other words, among the different levels of demand, the one that is balanced with the supply in the economy is called effective demand. It is this theory of effective demand that has remained neglected for more than 100 years and has gained importance with the emergence of Keynes's general theory. Keynes was interested in the problem of how much people intended to spend at different levels of income and employment, as it was these planned spending that determined the level of consumption and investment. Keynes' view was that people's spending intentions translated into aggregate demand. If aggregate demand, Keynes said, falls below the income businessmen expect to receive, there will be cuts in the production of goods leading to unemployment. On the contrary, if aggregate demand exceeds expectations, production will be stimulated.

In any community, effective demand represents the money people actually spend on goods and services. The money that entrepreneurs receive flows into the factors of production in the form of wages, rents, interest and profits. In this respect, effective demand (actual expenditure) corresponds to national income, which is the sum of the income of all members of the community. It also represents the value of community production, since the total value of national production is exactly equal to the income of entrepreneurs from the sale of goods. Moreover, all production is either consumer goods or capital goods; we can therefore say that effective demand is equal to national consumer spending plus capital goods.

Effective demand (ED) = national income (Y) = value of national production = expenditure on consumer goods (C) + expenditure on capital goods (I). Hence ED = Y = C + I = 0 = employment.

Importance of the Concept of Effective Demand:

The principle of effective demand is an integral part of Keynesian employment theory. The general theory has the basic observation that aggregate demand determines total employment. A lack of effective demand leads to unemployment. The principle of effective demand is important in the following points. First, it can be said that with the help of the concept of effective demand, Say's market law was rejected. The concept of effective demand has shown beyond any doubt that whatever is produced is not automatically consumed and income is not spent in such a way that the factors of production are fully used. Second, an analysis of effective demand also reveals the inherent contradictions in Pigou's plea that wage cuts will eliminate unemployment. Keynes believes that wage cuts may or may not increase employment as the level of employment depends on the level of real demand.

Third, the effective demand principle could explain how and why depression might persist. Keynes explained that effective demand is consumption and investment. As employment increases, so does income, leading to an increase in consumption, but by less than the increase in income. Thus, consumption lags and becomes the main reason for the gap that exists between total income and total expenditure in order to maintain effective demand at an earlier (or original) level, namely a real investment that corresponds to the gap between income and consumption, it has to be done. In other words, employment can only grow if investment increases. Here the principle of effective demand has the greatest importance. It makes it clear that investments rule the quarter. Fourth, the demand side is moving into the spotlight. In contrast to the classic emphasis on the supply side, Keynes placed great emphasis on the demand side and attributed fluctuations in employment to changes in demand. Effective demand theory illustrates how and why aggregate demand becomes deficient in a capitalist economy, and how a lack of effective demand leads to depression.

Determinants of Effective Demand:

To understand Keynes' employment theory and how employment equilibrium arises in the economy, we need to understand the determinants of the aggregate demand function and the aggregate supply function and their interrelationships.

- Aggregate Demand Function and

- Aggregate Supply Function.

1. Aggregate Demand Function: The aggregated demand function relates each employment level to the expected revenue from the sale of production from this employment volume. How high the expected sales revenue will be depending on people's expected spending on consumption and investment. Every producer in a free enterprise economy tries to estimate the demand for his product and calculate in advance the profit that will likely be made from his sales proceeds. The total sum of the income payments to the production factors in the production process forms its factor costs. The factor cost and the entrepreneur's profit thus give us the total income or the proceeds that result from a certain amount of employment in a company. Keynes brought this idea into macroeconomics. We can calculate total income or total sales revenue. This total income, or the total revenue expected from a given amount of employment, is called the "total demand price" of the production of that amount of employment; H. It represents expected revenue when employees are offered a certain volume of employment.

Entrepreneurs make decisions about the amount of employment they offer the job based on sales expectations and expected profit, which in turn depend on an estimate of the total money (income) they will get from selling goods that are manufactured at different levels of employment. The sales revenue they expect is the same as what they expect from the community for their production.

Fig 9

A schedule for the income from the sale of outputs resulting from different levels of employment is called an aggregate demand plan, or aggregate demand node. The total demand function shows the increase in the total demand price with increasing employment and thus increasing production. Thus, the aggregate demand plan is an increasing function of the amount of employment. The question can reasonably be asked: Why did Keynes relate expected sales revenue to employment through manufacturing and why not directly to manufacturing?

Three possible reasons may be given for this:

(i) Keynes was mainly interested in the factors that determine employment rather than production.

(ii) Employment and production are moving in all respects in the same direction in a short space of time;

(iii) Total production in the economy is made up of a multitude of goods and there is no better measure of it than the labor force employed. If D represents the revenue that entrepreneurs expect from employing N men, the aggregate demand function can be written as D = f (N), which shows a relationship between D and N. The total demand function or the demand plan ADF is shown. We find in the figure that the A dadoes do not start from the origin O, since even with a low level of employment; consumption will be well above income. If we move to the right along the ADF curve, we find that it becomes flatter due to the law of psychological consumption. But the ADF can never fall just because absolute consumption in the economy can never fall.

2. Aggregate Supply Function:

The total offer relates to the production of companies. Entrepreneurs, in providing jobs for workers, need to be sure that the output they produce is sold out and that they are able to meet their production costs and also achieve the expected profit margin. A company's production can be sold at different prices depending on market conditions. However, there is some income from the output for which the entrepreneurs feel that it is only worthwhile to provide a certain number of jobs. The expected minimum sales revenue of production, which results from a certain amount of employment, is referred to as the "total supply price" of this production. In other words, these are the minimum expected earnings that are seen as only necessary to induce entrepreneurs to provide a certain number of jobs. For the whole economy at a certain level of employment, the total offer price is the total amount (sales revenue) that all producers together have to expect from the sale of the production produced by that particular number of men, if it is only to be worthwhile to employ.

A schedule of the minimum earnings required to induce entrepreneurs to give different amounts of employment is called a comprehensive pension plan. This is also an increasing function of the amount employed. In other words, the minimum sales revenue requirement continues to rise as employment and output rise. This is due to the increase in production costs with increasing production, since capital, production techniques and organization are taken into account in the short term. It should be noted here that the total demand function is the expected sales revenue that we take into account, and the total supply function is the required minimum sales revenue. There will be a difference between them as at certain levels of employment (outputs) the producers expect more income than the minimum sales revenue required. There will be other levels of employment where the expected sales proceeds may be less than the required sales proceeds.

The aggregate supply function ASF is shown in Figure 9 in such a way that it increases gradually and then quickly from left to right. The ASF becomes vertical after point S2, because at this level of the total supply all those who want to be employed receive employment. This point indicates full employment in the economy. Determination of the employment level: In Fig. 9 ADF is the aggregate demand function and ASF is the aggregate supply function. We show employment along the X axis and sales revenue along the Y axis. The point E, at which the ADF curve intersects the aggregate supply curve, is called the effective demand point. It can be noted that there are so many points on the aggregate demand curve ADF, but all of these points except for point E are ineffective. In the diagram, the aggregate supply function shows the minimum revenues that are only required to induce entrepreneurs to provide different amounts of employment. The aggregated demand function shows the revenue from the sale of outputs from different employment levels.

Before these curves intersect at E, ASF is below ADF, so that at one level of employment the expected sales revenue N1D1 is higher than the required minimum sales revenue N1S1, which shows that employers are being induced to provide more employment. At point E, ADF is cut through by ASF and the expectations of the entrepreneurs for the proceeds are met. Point E is called the equilibrium point because it determines the actual level of employment (ON) at a given point in time in an economy. The employment level ON2 is not an equilibrium level as the expected sales revenue N2D2 is less than the sales revenue required for N2S2 at this employment level. Most entrepreneurs will be disappointed and reduce employment.

This is how we see it: the intersection of the aggregate demand plan with aggregate supply determines the actual level of employment in an economy, and at that level of employment, the amount of sales revenue that entrepreneurs expect is what they need to get when the cost is at that level of employment just cover. Underemployment Equilibrium: It can be noted, however, that the economy is undoubtedly in equilibrium at time E, since this is where entrepreneurs do not tend to increase or decrease employment. But Keynes makes a unique contribution to economic analysis by saying that E may or may not be a point of full employment equilibrium.

However, when some workers still remain unemployed after balancing the ADF and ASF, this is known as the underemployment balance. Keynes argued that way. Total demand and total supply could be the same with full employment. This is the case when the investment equals the gap between the total supply price for full employment and the amount that consumers spend on consumption from full employment income. Keynes believed that private investment in a capitalist economy was never enough to fill such a void. Therefore, there is every likelihood that the aggregate demand function and the aggregate supply function will intersect at a point below the underemployment equilibrium known as underemployment. If the underemployment equilibrium is the usual situation in the capitalist economy, then how can we achieve full employment? 7 Keynes suggested that in a short period of time the government could increase aggregate demand in the economy through public investment that was not for profit.

Suppose the government makes an investment of D2S2, which raises the ADF to the level of the ADF and the demand function reduces the supply function at S2. The vertical line from point S2 down on the horizontal axis shows that this public investment policy would achieve full employment ON2 in the economy.

Forms of ASF and ADF: It is very difficult to comment on the forms of aggregate demand and supply. Assuming that the money prices of all commodities are constant and that employment and production rise and fall proportionally, we can safely conclude that both the aggregate demand function and the aggregate supply function increase the employment functions; then climb from left to top to the right. The ADF rises quite steeply at first and then flattens out and flattens out. This is because (type of consumption function) MFC is less than one. The ISF rises slowly at first due to the available resources for the unemployed. In view of bottlenecks in production, falling returns (rising costs) are becoming increasingly evident. Beyond full employment, production cannot be increased at all. The sharply rising ASF becomes vertical beyond the full employment point (S2).

Relative Importance of ASF and ADF Functions: Since the equilibrium level of employment is determined by the overlap between these two schedules, it would be useful to learn more details about the nature and nature of these schedules. Of the two, little is important for the aggregate supply function. Keynes pays little attention to the function of total supply and focuses more on the function of total demand. For all practical purposes he takes ASF as given, because he deals with the short time and the delivery conditions cannot be changed in the short time. In addition, Keynes' General Theory dealt with an economy faced with unemployment of resources during the Depression. Under such circumstances, the manipulation of technical production conditions like costs, machines and materials through schemes like rationalization can do little. Rationalization leads to more unemployment in a short time. For these reasons Keynes took ASF for granted.

Since the delivery conditions had to be taken as given Keynes placed more emphasis on the aggregate demand function. Given the timing of aggregate supply, an economy's resources would only be fully utilized if there is sufficient aggregate demand. It is for this reason that some economists call his theory of employment a "theory of aggregate effective demand". Aggregate demand depends on consumption and investment. If employment is to be developed, consumption and investment spending must be accelerated. Thus, the shape and position of the aggregate demand function depend on the total expenditure incurred by a community for consumption and investment taken together. Assuming, as Keynes describes, the aggregate supply function to be given, the gist of his argument in general theory is that employment is determined by aggregate demand, which in turn depends on the propensity to consume and the amount of the investment at a given time.

Aggregate demand in the statistical sense is composed as follows:

(i) Private consumption expenditure,

(ii) Private investment expenditure,

(iii) Public investment expenditure,

(iv) External expenditure on national goods and services, in addition to expenditure domestic goods and services. In this way, aggregate demand is a flow of monetary expenditure on final output during a given period. All of these are components of effective demand

References:

- Https://www.britannica.com/topic/wage-theory

- Https://www.economicsdiscussion.net/classical-theory-of-employment/classical-theory-on-wage-and-employment-with-diagram-macro-economics/14599

- File:///C:/Users/INDIA/Downloads/1963_Bookmatter_TheTheoryOfWages.pdf

- Https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_General_Theory_of_Employment,_Interest_and_Money

- Https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_General_Theory_of_Employment,_Interest_and_Money