Unit - 2

Law of copy rights

Copyright is a form of intellectual property protection granted under Indian law to the creators of original works of authorship such as literary works (including computer programs, tables and compilations including computer databases which may be expressed in words, codes, schemes or in any other form, including a machine readable medium), dramatic, musical and artistic works, cinematographic films and sound recordings. Under section 13 of the Copyright Act 1957, copyright protection is conferred on literary works, dramatic works, musical works, artistic works, cinematograph films and sound recording. For example, books, computer programs are protected under the Act as literary works.

Fundamental principles of copyright

The fundamental principles of copyright are-

- Copyright law applies to nearly all creative and intellectual works.

A wide and diverse range of materials are protectable under copyright law. Books, journals, photographs, art, music, sound recordings, computer programs, websites, and many other materials are within the reach of copyright law. Also protectable are motion pictures, dance choreography, and architecture. If you can see it, read it, hear it, or watch it, chances are it is protectable by copyright law.

2. Works are protected automatically, without copyright notice or registration.

Works are protected under copyright if they are "original works of authorship" that are "fixed in any tangible medium of expression." In other words, once you create an original work, and fix it on paper, in clay, or on the drive of your computer, the work receives instant and automatic copyright protection. The law provides some important benefits if you do use the notice or register the work, but you are the copyright owner even without these formalities.

3. Copyright protection lasts for many decades.

The basic term of protection for works created today is for the life of the author, plus seventy years. In the case of "works made for hire" (explained below), the copyright lasts for the lesser of either 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation of the work. The rules for works created before 1978 are altogether different, and foreign works often receive distinctive treatment. Not only is the duration of copyright long, but the rules are fantastically complicated.

4. Works in the public domain.

Some works lack copyright protection, and they are freely available for use without the limits and conditions of copyright law. Copyrights eventually expire, and the works enter the public domain. Works produced by the U.S. Government are not copyrightable. Copyright also does not protect facts, ideas, discoveries, and methods.

Fundamental of copyright law of India

The Copyright Act, 1957 provides copyright protection in India. It confers copyright protection in the following two forms:

(A) Economic Rights:

The copyright subsists in original literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works; cinematographs films and sound recordings. The authors of copyright in the aforesaid works enjoy economic rights u/s 14 of the Act. The rights are mainly, in respect of literary, dramatic and musical, other than computer program, to reproduce the work in any material form including the storing of it in any medium by electronic means, to issue copies of the work to the public, to perform the work in public or communicating it to the public, to make any cinematograph film or sound recording in respect of the work, and to make any translation or adaptation of the work. In the case of computer program, the author enjoys in addition to the aforesaid rights, the right to sell or give on hire, or offer for sale or hire any copy of the computer program regardless whether such copy has been sold or given on hire on earlier occasions. In the case of an artistic work, the rights available to an author include the right to reproduce the work in any material form, including depiction in three dimensions of a two-dimensional work or in two dimensions of a three-dimensional work, to communicate or issues copies of the work to the public, to include the work in any cinematograph work, and to make any adaptation of the work. In the case of cinematograph film, the author enjoys the right to make a copy of the film including a photograph of any image forming part thereof, to sell or give on hire or offer for sale or hire, any copy of the film, and to communicate the film to the public. These rights are similarly available to the author of sound recording. In addition to the aforesaid rights, the author of a painting, sculpture, drawing or of a manuscript of a literary, dramatic or musical work, if he was the first owner of the copyright, shall be entitled to have a right to share in the resale price of such original copy provided that the resale price exceeds rupees ten thousand.

(B) Moral Rights:

Section 57 of the Act defines the two basics 'moral rights of an author. These are:

i) Right of paternity

Ii) Right of integrity.

The right of paternity refers to a right of an author to claim authorship of work and a right to prevent all others from claiming authorship of his work. Right of integrity empowers the author to prevent distortion, mutilation or other alterations of his work, or any other action in relation to said work, which would be prejudicial to his honour or reputation.

The provision to section 57(1) provides that the author shall not have any right to restrain or claim damages in respect of any adaptation of a computer program to which section 52 (1) (aa) applies (i.e., reverse engineering of the same). It must be noted that failure to display a work or to display it to the satisfaction of the author shall not be deemed to be an infringement of the rights conferred by this section. The legal representatives of the author may exercise the rights conferred upon an author of a work by section 57(1), other than the right to claim authorship of the work.

Key takeaways

Copyright is a form of intellectual property protection granted under Indian law to the creators of original works of authorship such as literary works (including computer programs, tables and compilations including computer databases which may be expressed in words, codes, schemes or in any other form, including a machine readable medium), dramatic, musical and artistic works, cinematographic films and sound recordings.

Originality is an important legal concept with respect to copyright. Originality is the aspect of a created or invented work that makes it new or novel, and thereby distinguishes it from reproductions, clones, forgeries, or derivative works. In this regard, an original work stands out because it was not copied from the work of others. “Originality” is a constitutional requirement for copyright applicability even though it was first stated explicitly by statute only with the introduction of the 1976 Copyright Act. In the case of Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service, the U.S. Supreme Court explained that the requirement of originality is not particularly stringent and is comprised of two elements: that the work be independently created by the author (as opposed to copied from other works) and that it possesses at least some minimal degree of creativity. A work satisfies the “independent creation” element so long as it was not literally copied from another, even if it is fortuitously identical to an existing work. The “creativity” element sets an extremely low bar that is cleared quite easily. It requires only that a work possess some creative spark, no matter how crude, humble, or obvious it might be.

Under section 13 of India’s Copyright Act, 1957, copyright can subsist only in “original” literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works. The act does not define “original” or “originality” and what these concepts entail has been the subject-matter of judicial interpretations in India and various other jurisdictions. As copyright law protects only the expression of an idea, and not the idea itself, the “work” must originate from the author and the idea need not necessarily be new. Views diverge with respect to two important doctrines pertaining to how originality accrues in any copyrighted work: the “sweat of the brow” doctrine and the “modicum of creativity” doctrine. These are the two tests on each end of the debate for ascertaining “originality”. Two tests are to be followed to decide the "Originality" of a work: -

- Non- copying requirement (completely objective test)

- Threshold/Degree of originality (varies from court to court)

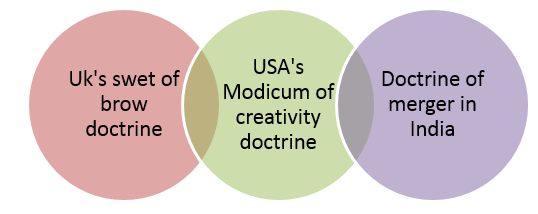

There are different doctrines used in different jurisdictions of law, which are analysed following:

Figure: Doctrine or originality used in different jurisdiction of law

- UK's Sweat of the brow doctrine

According to this doctrine, an author gains rights through simple diligence during the creation of a work. The "sweat of the brow" doctrine relies entirely on the skill and labour of the author, rendering the requirement of "creativity" in a work nearly redundant. This doctrine was first adopted in the UK in 1900 in the case of Walter v Lane,1 where an oral speech was reproduced verbatim in a newspaper report and the question was whether such verbatim reproduction would give rise to copyright in the work. Court held that the work has copyright protection.

In University of London Press v. University Tutorial Press the test of "originality" was explained by the Chancery Division of England which is also commonly cited as an archetypal "sweat of the brow". The Court held that the Copyright Act does not require that expression be in an original or novel form. It does, however, require that the work not be copied from another work. It must originate from the author. The question papers are original within the meaning of copyright laws as they were originated from the authors. The court held that merely because similar questions have been asked by other examiners, the plaintiff shall not be denied copyright. This doctrine is also followed in various other jurisdictions including Canada, Australia and India.

2. USA's Modicum of creativity doctrine

USA has the oldest and the most developed Copyright laws in the world. The courts have given importance to both the creative and subjective contribution of the authors since the late 17th century. In Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural telephone Service Co.3 case, the US Supreme Court totally negated this doctrine and held that in order to be original a work must not only have been the product of independent creation, but it must also exhibit a "modicum of creativity". This doctrine stipulates that originality subsists in a work where a sufficient amount of intellectual creativity and judgment has gone into the creation of that work. The standard of creativity need not be high but a minimum level of creativity should be there for copyright protection. The major question of law was whether a compilation like that of a telephone directory is protected under the Copyright law? The court held that the facts like names, addresses etc are not copyrightable, but compilations of facts are copyrightable. This is majorly owing to the unique way of expression by way of arrangement and if it possesses at least some minimal degree of creativity, it will be copyrightable. The Court held that Rural's directory displayed a lack of requisite standards for copyright protection as it was just a compilation of data without any minimum creativity, which was a requirement for copyright protection. Hence, Rural's case was dismissed.

3. Doctrine of merger in India

India strongly followed the doctrine of 'sweat of the brow' for a considerably long time. However, the standard of 'originality' followed in India is not as low as the standard followed in England. In Eastern Book Company v. D.B. Modak, where the Supreme Court discarded the 'Sweat of the Brow' doctrine and shifted to a 'Modicum of creativity' approach as followed in the US. The dispute is relating to copyrightability of judgements. The notion of "flavour of minimum requirement of creativity" was introduced in this case. The Court granted copyright protection to the additions and contributions made by the editors of SCC. At the same the Court also held that the orders and judgments of the Courts are in public domain and everybody has a right to use and publish them and therefore no copyright can be claimed on the same.

Key takeaways

Originality is an important legal concept with respect to copyright. Originality is the aspect of a created or invented work that makes it new or novel, and thereby distinguishes it from reproductions, clones, forgeries, or derivative works.

The right of reproduction commonly means that no person shall make one or more copies of a work or of a substantial part of it in any material form including sound and film recording without the permission of the copyright owner. The most common kind of reproduction is printing an edition of a work. Reproduction occurs in storing of a work in the computer memory. The reproduction right grants the copyright owner the ability to control the making of a copy of the work. It is arguably the most important of the rights as it is implicated in most copyright infringement disputes. Some examples of activities that implicate the reproduction right include pasting a news article into an email, photocopying a magazine, uploading movies or music to a website, copying a computer program or a document onto a PC, scanning or digitizing printed text or images into a digital file, or right clicking on an online photograph or other image to copy it or save it to a PC. If these types of activities are not authorized or otherwise allowed by the law, for instance under the fair use exception, they may infringe the copyright owner’s reproduction right(s).

The Copyright Act covers reproduction in any form.

- Infringement of the Reproduction Rights

It is not necessary that the entire original work be copied for an infringement of the reproduction right to occur. All that is necessary is that the copying be substantial and material.

2. Reproduction for Blind or Other People with Disabilities Exception

It is not an infringement of copyright for an authorized entity to reproduce copies or phonon records of a previously published, nondramatic literary work if such copies or phone records are reproduced in specialized formats exclusively for use by blind or other persons with disabilities.

3. Reproduction by Libraries and Archives Exception

It is not an infringement of copyright for a library or archives, or any of its employees acting within the scope of their employment, to reproduce no more than one copy or phone record of a work, with a few exceptions and under certain conditions.

Key takeaways

The right of reproduction commonly means that no person shall make one or more copies of a work or of a substantial part of it in any material form including sound and film recording without the permission of the copyright owner.

The owner of the copyright has the right to publicly perform his works. Example, he may perform dramas based on his work or may perform at concerts, etc. This also includes the right of the owner to broadcast his work. This includes the right of the owner to make his work accessible to the public on the internet. This empowers the owner to decide the terms and conditions to access his work. To perform or display a work “publicly” means —

(1) to perform or display it at a place open to the public or at any place where a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances is gathered; or

(2) to transmit or otherwise communicate a performance or display of the work to a place specified by clause (1) or to the public, by means of any device or process, whether the members of the public capable of receiving the performance or display receive it in the same place or in separate places and at the same time or at different times.

Key takeaways

The owner of the copyright has the right to publicly perform his works. Example, he may perform dramas based on his work or may perform at concerts, etc.

First owner of copyright (section 17)

Subject to the provisions of this Act, the author of a work shall be the first owner of the copyright therein:

Provided that—

(a) in the case of a literary, dramatic or artistic work made by the author in the course of his employment by the proprietor of a newspaper, magazine or similar periodical under a contract of service or apprenticeship, for the purpose of publication in a newspaper, magazine or similar periodical, the said proprietor shall, in the absence of any agreement to the contrary, be the first owner of the copyright in the work in so far as the copyright relates to the publication of the work in any newspaper, magazine or similar periodical, or to the reproduction of the work for the purpose of its being so published, but in all other respects the author shall be the first owner of the copyright in the work;

(b) subject to the provisions of clause (a), in the case of a photograph taken, or a painting or portrait drawn, or an engraving or a cinematograph film made, for valuable consideration at the instance of any person, such person shall, in the absence of any agreement to the contrary, be the first owner of the copyright therein;

(c) in the case of a work made in the course of the author’s employment under a contract of service or apprenticeship, to which clause (a) or clause (b) does not apply, the employer shall, in the absence of any agreement to the contrary, be the first owner of the copyright therein;

(d) in the case of a Government work, Government shall, in the absence of any agreement to the contrary, be the first owner of the copyright therein;

(e) in the case of a work to which the provisions of section 41 apply, the international organization concerned shall be the first owner of the copyright therein.

Assignment of copyright (section 18)

(1) The owner of the copyright in an existing work or the prospective owner of the copyright in a future work may assign to any person the copyright either wholly or partially and either generally or subject to limitations and either for the whole term of the copyright or any part thereof:

Provided that in the case of the assignment of copyright in any future work, the assignment shall take effect only when the work will come into existence.

Provided also that the author of the literary or musical work included in a cinematograph film shall not assign or waive the right to receive royalties to be shared on an equal basis with the assignee of copyright for the utilization of such work in any form other than for the communication to the public of the work along with the cinematograph film in a cinema hall, except to the legal heirs of the authors or to a copyright society for collection and distribution and any agreement to contrary shall be void:

Provided also that the author of the literary or musical work included in the sound recording but not forming part of any cinematograph film shall not assign or waive the right to receive royalties to be shared on an equal basis with the assignee of copyright for any utilization of such work except to the legal heirs of the authors or to a collecting society for collection and distribution and any assignment to the contrary shall be void.

(2) Where the assignee of a copyright becomes entitled to any right comprised in the copyright, the assignee as respects the rights so assigned, and the assignor as respects the rights not assigned, shall be treated for the purposes of this Act as the owner of copyright and the provisions of this Act shall have effect accordingly.

(3) In this section, the expression “assignee” as respects the assignment of the copyright in any future work includes the legal representatives of the assignee, if the assignee dies before the work comes into existence.

Key takeaways

The owner of the copyright in an existing work or the prospective owner of the copyright in a future work may assign to any person the copyright either wholly or partially and either generally or subject to limitations and either for the whole term of the copyright or any part thereof:

Copyright is the right of ownership entitled to literature, drama, music, artworks, sound recordings, etc. Copyright registration grants a bundle of rights that comprise rights to reproduction, communication to the public, adaptation, and translation of the work. Registering a Copyright ensures certain minimum safeguards of the rights of ownership and enjoyment of the authors over their creations, which protects and rewards creativity. It is necessary to register for copyright because it makes you communicate to the public, reproduce the rights, adapt and translate the works.

Registrar and Deputy Registrar of Copyrights (Section 10)

(1) The Central Government shall appoint a Registrar of Copyrights and may appoint one or more Deputy Registrars of Copyrights.

(2) A Deputy Registrar of Copyrights shall discharge under the superintendence and direction of the Registrar of Copyrights such functions of the Registrar under this Act as the Registrar may, from time to time, assign to him; and any reference in this Act to the Registrar of Copyrights shall include a reference to a Deputy Registrar of Copyrights when so discharging any such functions.

Eligibility of copyright registration

- Copyright registration can be obtained for any works related to literature, drama, music, artwork, film, or sound recording. Copyrights are given to mainly three classes of work, and each class has its distinctive right under the copyright act.

- Original literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works comprise the copyright for books, music, painting, sculpture, etc.

- Cinematography films are another class of copyright that consists of any work of visual recording on any medium.

- Sound recordings have a distinctive class under the copyright act that consists of a recording of sounds, regardless of the medium on which such recording is made or the method by which the sound is produced.

Process for copyright registration

The Copyright registration application can be made on Form IV in a requisite manner and the applicable fees. Irrespective of it is published or unpublished work, it can be copyrighted. For published work, three copies of the published work need to be presented along with the application. While for unpublished work, a copy of the manuscript needs to be sent along with the application for affixing the stamp of the copyright office is proof of the work having been registered. Here is the step-by-step process for getting copyright registration in India:

Figure: Copyright registration process

- The application for copyright registration has to be filed in the concerned forms that mention the particular's work. Depending on the type of the work, a separate copyright application may have to be filed.

- The applicant needs to sign the forms, and the Advocate must submit the application under the name the POA has been executed. Meanwhile, our experts will prepare the copyright registration application and submit the necessary forms with the Registrar of copyrights.

- The Diary number will be issued once the application is submitted online.

- Within the waiting period of 30 days, the copyright examiner reviews the application for potential objection or any other discrepancies.

- If there is an objection, a notice will be issued, and the same has to be compiled within 30 days from the date of issuance of the notice. The examiner may call both parties for a hearing.

- After the discrepancy has been removed or no objection, the copyright is registered, and the Copyright Office will issue the registration certificate.

Key takeaways

Copyright is the right of ownership entitled to literature, drama, music, artworks, sound recordings, etc. Copyright registration grants a bundle of rights that comprise rights to reproduction, communication to the public, adaptation, and translation of the work.

The use of the notice is the responsibility of the copyright owner and does not require permission from, or registration with, the Copyright Office. Use of the notice informs the public that a work is protected by copyright, identifies the copyright owner, and shows the year of first publication.

Form and Placement of the Copyright Notice:

The copyright notice generally consists of three elements:

- The symbol © (the letter C in a circle), or the word "Copyright" or the abbreviation "Copr.";

- The year of first publication of the work; and

- The name of the owner of copyright in the work.

Figure: Elements of corporate notice

Example: © 1996 Jane Doe

If the work is unpublished, the appropriate format for the notice includes the phrase "Unpublished Work" and the year of creation. Example: Unpublished Work © 1995 John Doe.

The essentials of placement of copyright notice are discussed below-

- The "C in a circle" notice is used only on "visually perceptible copies." Certain kinds of works--for example, musical, dramatic, and literary works--may be fixed not in "copies" but by means of sound in an audio recording. Since audio recordings such as audio tapes and phonograph disks are "phone records" and not "copies," under the Copyright Act, the "C in a circle" notice is not used to indicate protection of the underlying musical, dramatic, or literary work that is recorded. Instead, a symbol composed of the letter "P" in a circle is used. Since computer software and apps for mobile devices are considered to be visually perceptible (with the aid of a machine), the copyright notice for software and apps should use the C in a circle format.

- The notice should be affixed to copies or phone records of the work in such a manner and location as to give reasonable notice of the claim of copyright. For computer software, the copyright notice is generally placed on the medium of distribution. If physical media is used to distribute the software, the notice should be placed on the disk that contains the software. If the software is downloaded, such as a mobile device app downloaded from an app store, a copyright notice should appear on the page or screen that is displayed when the product is downloaded. In addition, it is wise to make the copyright notice visible on the screen when the program is executed. One way of doing this is to include the notice on a splash screen that is temporarily shown when the program is initially executed.

- Copyright notice is no longer necessary for a work to be protected under copyright law. For any work published after March 1, 1989, the copyright notice is strictly optional, though highly recommended. However, if a work was first published before March 1, 1989, copyright notice was required for the work to be protected under copyright. Works that were published without a copyright notice prior to this date may have lost all right to copyright protection. Even though the copyright notice is no longer required, it should still be placed on all published works. Use of the notice is recommended for the following reasons:

- It informs the public that the work is protected by copyright (and thereby helps to scare aware potential infringers);

- It prevents a party from claiming the status of "innocent infringer," which may allow a party to escape certain damages under the Copyright Act; and

- It identifies the copyright owner and the year of first publication (so that third parties will know who to contact to request a license to the work).

There is no need to register the work with the Copyright Office or to seek any other kind of permission before using the copyright notice.

Key takeaways

The use of the notice is the responsibility of the copyright owner and does not require permission from, or registration with, the Copyright Office.

Each country has its own domestic copyright laws that apply to its own citizens, and also to the use of foreign content when used in one's country. It allows creators and content owners around the world and citizens of many countries to enjoy copyright protection in countries other than their own. Many copyright issues that appear to be national copyright issues are in fact international copyright issues. Copyright is a creation of law in each country, and therefore there is no such thing as an international copyright law. Nevertheless, nearly 180 countries have ratified a treaty – the Berne Convention, administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) – that sets a minimum set of standards for the protection of the rights of the creators of copyrighted works around the world.

Copyright protection under International copyright law

One of the basic principles of the Berne Convention is that of “automatic protection”, which means that copyright protection exists automatically from the time a qualifying work is fixed in a tangible medium (such as paper, film or a silicon chip).

A “qualifying work” is a

- Literary work

- a musical composition

- a film, a software program

- a painting

- Or any of many other expressions of creative ideas

– but it is only the expression, and not the idea, that is protected by copyright law.

Neither publication, registration, nor other action is required to secure a copyright, although in some countries use of a copyright notice is recommended, and in a few countries (including the United States) registration of domestic works is required in order to sue for infringement.

Figure: Logo of international copyright

The Berne Convention provides that, at a minimum, copyright protection in all signatory countries should extend to “literary and artistic works”, including “every production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain, whatever may be the mode or form of its expression.” The detailed list of categories of works that are protected by copyright – and the specific definition and scope of each of them – may slightly vary from country to country, but it generally includes scientific articles, essays, novels, short stories, poems, plays and other literary works; drawings, paintings, photographs, sculptures and other two- and three-dimensional pieces of art; films and other audio-visual works; musical compositions; software and others.

Duration under International copyright law

The duration of copyright may vary from country to country according to the type of work (and the particular right in question). Although Berne sets a minimum duration of a copyright in a literary work equal to the life of the author plus 50 years, in most cases and countries today, the general rule is that copyright in literary, dramatic, musical or artistic works lasts for the life of the author and then until 31 December of the year 70 years after his or her death (usually referred to as “life plus 70”). In some countries, specific rules may apply that alter or add to the general rule of life plus 70 years (for example, granting extensions for the period of World War II). In addition, some countries had different copyright terms that were in effect before adoption of the general rule. For example, the United States did not adopt a “life plus” copyright duration until 1978. These differences in national laws imply the fact that in some cases a specific work can still be in copyright in some countries but out of copyright (that is, in the public domain) in others.

Types of rights under the international copyright law

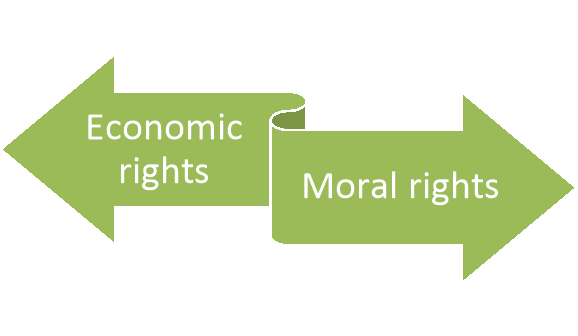

Most national copyright laws recognize two different types of rights within copyright:

Figure: Types of copyright

Countries in the Anglo-American tradition, including the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, tend to minimize the existence of moral rights in favor of an emphasis on economic rights in copyright.

- Economic rights

Economic or exploitation rights recognize the right of the holder to use, to authorize use of, or to prohibit the use of, a work, and to set the conditions for its use. Different specific uses (or “acts of exploitation”) of a work can be treated separately, meaning that the rights holder can deal with each right (including using, transferring, licensing or selling the right) on an individual type-of-use basis. Economic rights typically include:

a) The right of reproduction (for instance, making copies by digital or analogue means),

b) The right of distribution by way of tangible copies (for example, selling, renting or lending of copies),

c) The right of communication to the public (including public performance, public display and dissemination over digital networks like the Internet), and

d) The right of transformation (including the adaptation or translation of a text work).

e) Moral rights refer to the idea that a copyrighted work is an expression of the personality and humanity of its author or creator. They include:

f) The right to be identified as the author of a work,

g) The right of integrity (that is, the right to forbid alteration, mutilation or distortion of the work), and

h) The right of first divulgation (that is, making public) of the work.

2. Moral rights

Moral rights cannot always be transferred by the creator to a third party, and some of them do not expire in certain countries. They include:

a) The right to be identified as the author of a work,

b) The right of integrity (that is, the right to forbid alteration, mutilation or distortion of the work), and

c) The right of first divulgation (that is, making public) of the work.

Moral rights cannot always be transferred by the creator to a third party, and some of them do not expire in certain countries.

International copyright treaties

Several international treaties encourage reasonably coherent protection of copyright from country to country. They set minimum standards of protection which each signatory country then implements within the bounds of its own copyright law. Some of such treaties are-

Figure: International copyright treaties

- Berne Convention

It is the oldest and most important treaty. It was signed in 1886 (but has been revised many times since) and ratified by nearly 180. It establishes minimum standards of protection-

- Types of works protected

- Duration of protection

- Scope of exceptions

Some of the limitations of such principles are-

a) Principles such as “national treatment” (works originating in one signatory country are given the same protection in the other signatory countries as each grant to works of its own nationals)

b) Principles such as “automatic protection” (copyright inheres automatically in a qualifying work upon its fixation in a tangible medium and without any required prior formality).

2. WIPO Copyright Treaty

It was signed in 1996. It makes clear that computer programs and databases are protected by copyright. It recognizes that the transmission of works over the Internet and similar networks is an exclusive right within the scope of copyright, originally held by the creator. It categorizes as copyright infringements both

- The circumvention of technological protection measures attached to works

- The removal from a work of embedded rights management information.

3. The Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)

The WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) is the most comprehensive multilateral agreement on intellectual property (IP). It plays a central role in facilitating trade in knowledge and creativity, in resolving trade disputes over IP, and in assuring WTO members the latitude to achieve their domestic policy objectives. It frames the IP system in terms of innovation, technology transfer and public welfare. The Agreement is a legal recognition of the significance of links between IP and trade and the need for a balanced IP system. It was signed in 1996.

Key takeaways

Each country has its own domestic copyright laws that apply to its own citizens, and also to the use of foreign content when used in one's country. It allows creators and content owners around the world and citizens of many countries to enjoy copyright protection in countries other than their own.

A patent is a government granted right for a fixed time period to exclude others from making, selling, using, and importing an invention, product, process or design, or improvements on such items. Some of the important provisions provided under the Patent Act, 1970 are highlighted below-

- According section 2(m) of Patent Act, 1970, "patent" means a patent for any invention granted under this Act.

- According to section 2 (n) "patent agent" means a person for the time being registered under this Act as a patent agent.

- According to section 2 (o) "patented article" and "patented process" means respectively an article or process in respect of which a patent is in force.

- According to section 2 (p) "patentee" means the person for the time being entered on the register as the grantee or proprietor of the patent.

What are not inventions (Section 3)

The following are not inventions within the meaning of this Act, —

(a) an invention which is frivolous or which claims anything obviously contrary to well established natural laws;

(b) an invention the primary or intended use or commercial exploitation of which could be contrary to public order or morality or which causes serious prejudice to human, animal or plant life or health or to the environment;

(c) the mere discovery of a scientific principle or the formulation of an abstract theory or discovery of any living thing or non-living substance occurring in nature;

(d) the mere discovery of a new form of a known substance which does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance or the mere discovery of any new property or new use for a known substance or of the mere use of a known process, machine or apparatus unless such known process results in a new product or employs at least one new reactant.

(e) a substance obtained by a mere admixture resulting only in the aggregation of the properties of the components thereof or a process for producing such substance;

(f) the mere arrangement or re-arrangement or duplication of known devices each functioning independently of one another in a known way;

(g) Omitted by the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2002

(h) a method of agriculture or horticulture;

(i) any process for the medicinal, surgical, curative, prophylactic diagnostic, therapeutic or other treatment of human beings or any process for a similar treatment of animals to render them free of disease or to increase their economic value or that of their products.

(j) plants and animals in whole or any part thereof other than microorganisms but including seeds, varieties and species and essentially biological processes for production or propagation of plants and animals;

(k) a mathematical or business method or a computer programme per se or algorithms;

(l) a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work or any other aesthetic creation whatsoever including cinematographic works and television productions;

(m) a mere scheme or rule or method of performing mental act or method of playing game;

(n) a presentation of information;

(o) topography of integrated circuits;

(p) an invention which in effect, is traditional knowledge or which is an aggregation or duplication of known properties of traditionally known component or components.

Inventions relating to atomic energy not patentable (Section 4)

No patent shall be granted in respect of an invention relating to atomic energy falling within sub section (1) of section 20 of the Atomic Energy Act, 1962 (33 of 1962).

Inventions where only methods or processes of manufacture patentable (Section 5) [Omitted by the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005]

Persons entitled to apply for patents (Section 6)

(1) Subject to the provisions contained in section 134, an application for a patent for an invention may be made by any of the following persons, that is to say, —

(a) by any person claiming to be the true and first inventor of the invention;

(b) by any person being the assignee of the person claiming to be the true and first inventor in respect of the right to make such an application;

(c) by the legal representative of any deceased person who immediately before his death was entitled to make such an application.

(2) An application under sub-section (1) may be made by any of the persons referred to therein either alone or jointly with any other person.

Form of application (section 7)

(1) Every application for a patent shall be for one invention only and shall be made in the prescribed form and filed in the patent office.

(1A) Every international application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty for a patent, as may be filed designating India shall be deemed to be an application under this Act, if a corresponding application has also been filed before the Controller in India.

(1B) The filing date of an application referred to in sub-section (1A) and its complete specification processed by the patent office as designated office or elected office shall be the international filing date accorded under the Patent Cooperation Treaty.

(2) Where the application is made by virtue of an assignment of the right to apply for a patent for the invention, there shall be furnished with the application, or within such period as may be prescribed after the filing of the application, proof of the right to make the application.

(3) Every application under this section shall state that the applicant is in possession of the invention and shall name the person claiming to be the true and first inventor; and where the person so claiming is not the applicant or one of the applicants, the application shall contain a declaration that the applicant believes the person so named to be the true and first inventor.

(4) Every such application (not being a convention application or an application filed under the Patent Cooperation Treaty designating India) shall be accompanied by a provisional or a complete specification.

Key takeaways

A patent is a government granted right for a fixed time period to exclude others from making, selling, using, and importing an invention, product, process or design, or improvements on such items.

A patent (prior art) search is a process of identifying granted patents and published patent applications (collectively referred to as patent documents) that bear similarity to the subject matter which is of interest to party. A patent search is most often the first step in achieving different objectives, some of which are:

- Determining the probability of having a patent granted to a proposed invention

- Determining if you have the freedom to operate

- Determining if a granted patent can be invalidated

Based on the objective, the search strategy can vary to some extent. Also, in addition to conducting a search in patent databases, a search can be conducted to identify relevant non-patent literature. In this article however, we will be talking about carrying out a search to identify relevant patent documents using free online patent databases (although, in my opinion, paid databases add substantial value).

The free online patent databases I suggest are:

- Google Patents: Works best on Chrome and has a good search interface

- Espacenet: Good data coverage

- Freepatentsonline: Good search interface. Patent data coverage is not as good as Espacenet.

Strategies of patent search

The strategies of patent search are discussed below-

Figure: Strategies of patent search

1. Key string search

A key string search is an activity of querying a patent database using key strains that are formed using key words. A step-by-step process of carrying out a key string search is provided below:

- Identify words that define the features of your invention.

- Identify words that are synonymous to the words identified in the previous step.

- Form key strings that can be used as a search query in the database.

2. Patent classification search

Patent classification is a hierarchical system in which technology has been classified. Each patent application will be assigned one or more class based on the technology to which it relates. There are various classification systems, such as, US patent classification, European Classification (ECLA) and International Patent Classification (IPC). There are several ways of identifying the relevant IPC codes, some of which are:

- Browsing through the hierarchical IPC system. Note that the IPC system has ~ 69200 classes. Hence, some might find this approach tedious and ineffective.

- Identifying relevant IPC codes using “catchwords”. A list of catchwords can be accessed using the above link. Select catchwords that relate to your invention. Subsequently browse through the classes listed under the selected catchwords to select relevant IPC codes.

- Using the relevant/related patent references that you found using key word search to identify relevant IPC codes.

3. Citation based search

Citation is reference to prior technology. The references can be cited by a patent applicant or the patent examiner. Further, a patent document may have backward citations (references the patent document is citing) and forward citations (references that are citing the current patent document). One may consider both backward and forward citations (collectively called citations) for their search.

4. Assignee based search

To carry out assignee based search, extract a list of assignees/applicants from the list of relevant documents you found using the previous search strategies. In some cases, an assignee/applicant might have very few patents to their name. If there is less number of patents, then there is need to choose to review all the documents. However, if the assignee/applicant has more number of patent documents to their name, then they might have to add some limitation to the search query to reduce the number of results.

5. Inventor based search

Inventor based search is carried out by extracting a list of inventors’ name from the list of relevant documents you have found using the previous search strategies. The applicant can query the database using inventors’ name. After completing the assignee and inventor based search, if new relevant documents are found, then another round of citation search exercise using the newly found references would make the applicants search more comprehensive.

Key takeaways

A patent (prior art) search is a process of identifying granted patents and published patent applications (collectively referred to as patent documents) that bear similarity to the subject matter which is of interest to party.

Ownership rights of patentee

Grant of a Patent confers to a patentee the right to prevent others from making, using, exercising or selling the invention without his permission. The following ownership rights of patentee as provided under the Patent Act, 1970-

- Rights of patentees (Section 48)

Subject to the other provisions contained in this Act, a patent granted under this Act shall confer upon the patentee—

(a) where the subject matter of the patent is a product, the exclusive right to prevent third parties, who do not have his consent, from the act of making, using, offering for sale, selling or importing for those purposes that product in India;

(b) where the subject matter of the patent is a process, the exclusive right to prevent third parties, who do not have his consent, from the act of using that process, and from the act of using, offering for sale, selling or importing for those purposes the product obtained directly by that process in India.

- Rights of co-owners of patents (Section 50)

(1) Where a patent is granted to two or more persons, each of those persons shall, unless an agreement to the contrary is in force, be entitled to an equal undivided share in the patent.

(2) Subject to the provisions contained in this section and in section 51, where two or more persons are registered as grantee or proprietor of a patent, then, unless an agreement to the contrary is in force, each of those persons shall be entitled, by himself or his agents, to rights conferred by section 48 for his own benefit without accounting to the other person or persons.

(3) Subject to the provisions contained in this section and to any agreement for the time being in force, where two or more persons are registered as grantee or proprietor of a patent, then, a licence under the patent shall not be granted and share in the patent shall not be assigned by one of such persons except with the consent of the other person or persons.

(4) Where a patented article is sold by one of two or more persons registered as grantee or proprietor of a patent, the purchaser and any person claiming through him shall be entitled to deal with the article in the same manner as if the article had been sold by a sole patentee.

(5) Subject to the provisions contained in this section, the rules of law applicable to the ownership and devolution of movable property generally shall apply in relation to patents; and nothing contained in sub-section (1) or subsection (2) shall affect the mutual rights or obligations of trustees or of the legal representatives of a deceased person or their rights or obligations as such.

(6) Nothing in this section shall affect the rights of the assignees of a partial interest in a patent created before the commencement of this Act.

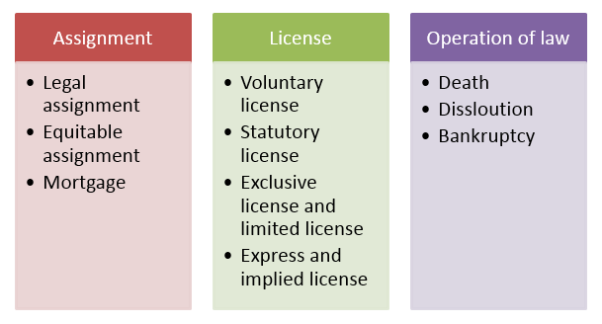

Transfer of ownership rights

The patentee can transfer his rights by using the following approaches/methods-

Figure: Transfer of ownership rights

1. Assignment

The term 'assignment' is not defined in the Indian Patents Act. Assignment is an act by which the patentee assigns whole or part of his patent rights to the assignee who acquires the right to prevent others from making, using, exercising or vending the invention. There are three kinds of assignments-

a) Legal Assignment: An assignment (or an agreement to assign) of an existing patent is a legal assignment, where the assignee may enter his name as the patent owner. A patent which is created by deed can only be assigned by a deed. A legal assignee entitled as the proprietor of the patent acquires all rights thereof.

b) Equitable Assignments: Any agreement including a letter in which the patentee agrees to give a certain defined share of the patent to another person is an equitable assignment of the patent. However an assignee in such a case cannot have his name entered in the register as the proprietor of patent. But the assignee may have notice of his interest in the patent entered in the register.

c) Mortgages: A mortgage is an agreement in which the patent rights are wholly or partly transferred to assignee in return for a sum of money. Once the assignor repays the sum to the assignee, the patent rights are restored to assignor/patentee. The person in whose favour a mortgage is made is not entitled to have his name entered in the register as the proprietor, but he can get his name entered in the register as mortgagee.

2. Licenses:

The Patents Act allows a patentee to grant a License by the way of agreement under section 70 of the Act. A patentee by the way of granting a license may permit a licensee to make, use, or exercise the invention. A license granted is not valid unless it is in writing. The license is contract signed by the licensor and the licensee in writing and the terms agreed upon by them including the payment of royalties at a rate mentioned for all articles made under the patent. Licenses are of the following types,

a) Voluntary licenses:

It is the license given to any other person to make, use and sell the patented article as agreed upon the terms of license in writing. Since it is a voluntary license, the Controller and the Central government do not have any role to play. The terms and conditions of such agreement are mutually agreed upon by the licensor and licensee. In case of any disagreement, the licensor can cancel the licensing agreement.

b) Statutory licenses:

Statutory licenses are granted by central government by empowering a third party to make/use the patented article without the consent of the patent holder in view of public interest. Classic example of such statutory licenses is compulsory licenses. Compulsory licenses are generally defined as "authorizations permitting a third party to make, use, or sell a patented invention without the patent owner's consent.

c) Exclusive Licenses and Limited Licenses:

Depending upon the degree and extent of rights conferred on the licensee, a license may be Exclusive or Limited License. An exclusive license excludes all other persons including the patentee from the right to use the invention. Any one or more rights of the patented invention can be conferred from the bundle of rights owned by the patentee. The rights may be divided and assigned, restrained entirely or in part. In a limited license, the limitation may arise as to persons, time, place, manufacture, use or sale.

d) Express and Implied Licenses:

An express license is one in which the permission to use the patent is given in express terms. Such a license is not valid unless it is in writing in a document embodying the terms and conditions. In case of implied license though the permission is not given in express terms, it is implied from the circumstances. For example: where a person buys a patented article, either within jurisdiction or abroad either directly from the patentee or his licensees, there is an implied license in any way and to resell it.

3. Transmission of Patent by Operation of law

- When a patentee dies, his interest in the patent passes to his legal representative;

- In case of dissolution or winding up of a company

- In case of bankruptcy transmission of patent by operation of law occurs.

Key takeaways

Grant of a Patent confers to a patentee the right to prevent others from making, using, exercising or selling the invention without his permission.

References:

1. Intellectual property right, Deborah, E. Bouchoux, cengage learning.

2. Intellectual property right - Unleashing the knowledge economy, prabuddhaganguli, Tata Mc Graw Hill Publishing Company Ltd.

Disclaimer: The contents/topics of the subject "Intellectual Property Rights" is either copied or collected from respective bare acts and websites. Hence the plagiarism issue should be ignored.