UNIT 4

Business Law

The Government adopted the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices (MRTP) Act in 1969 and accordingly the MRTP Commission was created in 1970. The Commission was found out to research the results of such practices, case by case, on the general public interest and to recommend suitable corrective measures.

The preamble to the MRTP Act described it as “An Act to supply that the operation of the economic system doesn't lead to the concentration of economic power to the common detriment for the control of monopolies, for the prohibition of monopolistic and restrictive trade practices and matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.”

The MRTP Act has made distention between monopolistic and restrictive trade practices. Accordingly, the monopolistic trade practices was described as “dominant firm practices”, i.e., a firm or a oligopolistic group of three firms, after attaining a dominant position has been “able to regulate the market by regulating prices or output or eliminating competition.”

Restrictive trade practices include concerted action undertaken by a group of two or more firms so on avoid competition from the market regardless of their market share. These sorts of practices are “deemed to be prejudicial to public interests.”

In order to form necessary review of the working of MRTP Act and to form necessary recommendation for streamlining its activity, the govt appointed a Sachar Committee in 1977. On the premise of the recommendations made by this committee, the govt made necessary amendments in Act in 1980 and also in 1984. In 1991, a major amendment was made where chapter (III) on Monopolies was dropped.

2. Inter-Connected and Dominant Undertakings of MRTP Act:

The MRTP Act analyses a business house in terms of inter-connected undertakings and dominant undertakings. Moreover, the MRTP Act broadly covered two sorts of undertakings, i.e., national companies or product monopolies. All the national monopolies were covered by section 20 (a) of the Act and that they include “single large undertakings” or “groups of inter-connected undertakings” which had assets to the extent of Rs 100 crore (in the pre-1985 period, the limit was fixed at Rs 20 crore).

Dominant undertakings, also referred to as product monopolies, were covered under section 20 (b) and that they include those undertakings which controlled to the minimum of one-fourth of production or market of a product and had assets to the minimum of Rs 3 crore (previously this limit was Rs 1 crore).

Thus, the massive industrial houses having inter-connections with variety of undertakings normally have countrywide concentration of economic power and industrial activity and thereby have substantial control on country’s resources. But the dominant undertakings are mostly dominant within one industry.

Companies under MRTP Act are normally required to get the approval of the govt in respect of:

(a) Substantial expansion of production capacity,

(b) Diversification of existing activities,

(c) Establishment of inter-connected undertakings,

(d) Amalgamation or merger with the other undertakings; and

(e) Takeover of the whole or a part of other undertakings.

The MRTP Commission normally considers of these kinds of proposals to justify its public interest. Till the top of March 1990, 1,854 undertakings were registered under the MRTP Act. Out of those , 1,787 undertakings were belonging to large industrial houses and therefore the remaining 67 undertakings were dominant undertakings.

Again, the economic Policy, 1991 has now totally scrapped the assets limit for MRTP companies.

The definition of ‘inter-connected companies’ as adopted under the MRTP Act, was having some loopholes, which have helped some industrial houses to flee from the purview of the Act. It's also found difficult to determine inter-connection in certain cases.

Mple, TELCO claimed that it had been not having any interconnection with any of the Tata company and Gwalior Rayon claimed that it had no inter-connection with any of the Birla company.

In this connection, Mr. N.K. Chandra observed that, “Under Indian conditions it's quite possible that two companies aren't ‘legally’ inter-connected, but are actually controlled by one business family. The widespread practice of benami shareholders whereby the de facto owner for a range of reasons has the shares recorded within the name of a relative or a protege, helps to underscore this above lacuna.”

The Dutt Committee had estimated that as per 1966 data there were 48 large industrial houses within the country having assets over Rs 21 crore each; they controlled together 1,500 companies with combined assets of Rs 4,000 crore. But, out of those , only 450 companies, having total assets worth Rs 1,000 crore registered themselves with the MRTP Commission.

Similarly, the Dutt Committee had also listed 280 companies under the Birla family out of which only 29 companies had registered themselves. Again the committee had listed 84 companies under the Tata’s (the top business houses) out of which only 14 concerns got them registered.

In order to review the effectiveness of MRTP Act, it might be better to assess the functioning of the MRTP commission. Whatever applications were received by the govt under Industrial Development and Regulation Act, only 10 per cent of it was named MRTP Commission. Out of those applications referred, only 87 per cent of the applications were approved.

In respect of identifying the massive business houses with inter-connected undertakings, the MRTP Act couldn't make much headway. Out of those inter-connected undertakings, only a couple of registered themselves with the MRTP Commission.

With the adoption of a liberal definition of the ‘Core Sector’ by the govt , even low-priority and highly profitable industries like man-made fibres and synthetic detergents are included within the core sector. During this connection, A.N. Oza stated, “The objectives of curbing the expansion of the large business houses and checking concentration of economic power must necessarily take a lowly place within the scheme of priorities.”

In 1995, a survey conducted by the Ministry of Industry and Civil Supplies revealed that there have been about 203 items during which there prevailed complete single firm monopoly. Moreover, in respect of single firm monopolies, both Monopolies Commission and therefore the powers of the govt under the MRTP Act were found to be ineffective.

In case of non-competing entrepreneurs, the question of intervening by the Commission becomes irrelevant. In respect of restrictive trade practices, the Commission works as a quasi-judicial tribunal which cannot impose any penalties and it's no authority to issue interim injunctions.

H.K. Paranjape, one among the previous members of MRTP Commission, observed that an in depth nexus between the political parties and therefore the ir leadership (especially the ruling party) and the large business houses exists and as a result there arises half-heartedness and soft pedaling of several measures proposed by the MRTP Commission.

Paranjape also argued that Section 27 incorporated to interrupt up large houses has hardly been applied since the inception of the Act. Under this context, the working of the MRTP Act reveals lack of commitment on the a part of the govt towards the Act. Under this tempo of economic liberalisation, the govt puts much emphasis on the rise within the volume of commercial production.

The problem of controlling economic concentration and monopolies got the secondary considerations as this objective is subdued by the objective of achieving higher industrial growth. The govt now felt that this MRTP limit has become deleterious in its effect, on the industrial growth of the country.

Thus, the new Industrial Policy, 1991 states that the pre- entry scrutiny of investment decisions by the so-called MRTP companies will not be required. But the new policy stated that the provisions of the MRTP Act are going to be strengthened so as to enable the MRTP Commission to require appropriate action in respect of monopolistic, restrictive and unfair trade practices.

The MRTP Act has defined the monopolistic, restrictive and unfair trade practices.

As per MRTP Act, a monopolistic trade practice (MTP) may be a quite trade practice which has the effect of:

(a) Maintaining unreasonable level of prices,

(b) Preventing or reducing competition unreasonably,

(c) Limiting technical development detrimental to common interest, or

(d) Allowing quality deterioration, and

(e) As per 1984 amendment unreasonably increasing the cost of production and prices of goods and services.

Again as per MRTP Act, a restrictive trade practice (RTP) indicates a trade practice which has the effect of preventing, distorting or restricting competition during a manner obstructing the flow of capital into production stream and bringing manipulation of prices or conditions of delivery or affecting the flow of supplies within the market, leading to unjustified costs or restrictions on consumers.

The 1984 amendment to the MRTP Act extended it to unfair trade practices, which include:

(a) The publication of an oral or in writing statement by visible demonstration;

(b) Publication of any advertisement matter purchasable at bargain price;

(c) Allowing enticement by gift or contest;

(d) Sale or supply of sub-standard goods and

(e) Hoarding or causing destruction of products and refusing to sell the merchandise .

The Preview of the MRTP Act:

Under the purview of MRTP Act, a large number of various kinds of agreements were identified. Each of such agreements was required to be duly registered with the Registrar of Restrictive Trade Practices alongside the names of the parties involved within the agreement.

All these registered undertakings were subject to following sorts of control on their different industrial activities:

(a) while proposing to expand the activities of the undertakings substantially by issuing fresh capital or by installing new machineries, notice to the Central Government was required to be given for getting approval (Section 21);

(b) while proposing to determine a new undertaking, prior permission of the Central Government was required to be obtained (Section 22); and

(c) while proposing to accumulate , merge or amalgamate with another undertaking, the sanction of the Central Government must be taken before the execution of such proposal (Section 23).

The entire responsibility to seem after the occurrence of concentration of economic power to the common detriment was on the govt . If it so desires, it could refer the interest the MRTP Commission for making an enquiry. But MRTP Commission has been given an advisory role because the ultimate orders, on any proposal need to be gone by the govt of the day.

The MRTP Act was formulated with following objectives:

(a) to have a careful watch that the operation of the economic system doesn't create any concentration of economic power to the detriment of the common people of the country;

(b) to regulate monopolies prevailing within the country; and

(c) to have a check on monopolistic, restrictive and unfair trade practices within the country.

Thus, so as to realize these objectives, the MRTP Act tries to control the activities of the large business houses and dominant undertakings of the country.

The process of Liberalisation in the MRTP Act:

The Government has been liberalizing the MRTP Act during different periods. With the gradual liberalisation of the Act, the large business houses are allowed to enter into variety of industrial fields which were previously closed for such houses, As a first step, the govt has reversed the policy by allowing the large industrial houses to set up industries in 90 “zero industry” districts of the country along side the advantages of transport subsidy and cost compensatory measures.

The Government introduced the primary amendment to the MRTP Act in November 1981 and therefore the subsequent second amendment in August 1982. The first amendment revised the definition of dominant undertakings along with the definition of the term production of an undertaking so on mean goods produced by it for the domestic market.

The 1982 amendment classified the dominant undertakings covered under Industrial Development and Regulation Act into those having licensed capacity et al. Not having licensed capacity.

Another important change within the MRTP Act was related to the power given to the govt. So on grant outright exemption in respect of certain proposals for considerable expansion and also new units from the purview of MRTP Act.

These exemptions are mostly associated with the proposals of

(a) Industry of high national priority,

(b) Raising production exclusively for export and

(c) Industry which is established or proposed to be established during a free trade zone.

The MRTP (Amendment) Act, 1984 has also introduced some changes within the MRTP Act on the premise of the experience gathered by the govt and as per recommendations made by the Sachar Committee. The amendment made an attempt to clarify certain definitions for including certain categories which were earlier left uncovered.

These changes within the definition were mostly related to:

(a) Definition of goods as per sale of goods Act, 1930;

(b) Change within the concept of group to include those enterprises under an equivalent management;

(c) Redefine inter-connected undertakings by reducing the control of voting power from l/3rd control over voting power to 25 per cent;

(d) Exemption of restrictions on capacity expansion to the extent of 25 per cent of licensed capacity;

(e) Giving power to the Central Government for severance of interconnection; and

(f) Including unfair trade practices like misleading advertisements; bargain selling etc. within the purview of MRTP Act.

Moreover, as per the advice of the Sachar Committee, the monopolies within the public sector are included by the govt within the purview of the MRTP Act.

Besides, a number of relaxations are announced by the govt to liberalise the businesses from the purview of MRTP Act.

These relaxations include:

(i) Opening from a good number of industries to large houses as per the 1973 industrial policy statement;

(ii) To introduce section 22-A within the MRTP Act for providing fillip to production in industries of high national priority and also for export;

(iii) Allowing 5 per cent automatic growth once a year in export-oriented industries,

(iv) Permitting use of existing capacities without MRTP clearance for other related items produced by machine tools industry, electrical equipment industry, steel forging and steel ingot industry;

(v) Liberalizing industrial licensing policy in 1985 by the Government; permitting the unrestricted entry of huge industrial houses and FERA Companies into another 21 technology items of manufacture;

(vi) Removing the sick industrial companies from the purview of MRTP Act under the provision of the Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provision) Bill, 1985;

(vii) Extending the scheme of de-licensing in March 1986 to MRTP/FERA Companies in respect of 20 industries of Appendix I (later on extended to 47 industries) for promoting the event of backward areas;

(viii) Automatic re- endorsement of capacity at the highest level of production achieved during 1988 and 1990;

(ix) Freeing dominant undertakings from industrial licensing policy restrictions applicable under the MRTP Act; and

(ix) Raising the limit of assets for the aim of MRTP Act from Rs 20 crore to Rs 100 crore and finally; the New Industrial Policy, 1991 scrapped the asset limit for MRTP Companies altogether.

The Competition Act, 2002 was enacted by way of the Parliament of India and governs Indian competition law. It replaced the archaic The Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act, 1969. Under this legislation, the Competition Commission of India was established to forestall the activities that have an adverse effect on competition in India. This act extends to complete of India except the State of Jammu and Kashmir.

An Act to give, keeping in view of the economic development of the country, for the establishment of a Commission to prevent practices having adverse effect on competition, to promote and sustain opposition in markets, to protect the interests of consumers and to ensure freedom of exchange carried on by other participants in markets, in India, and for matters related therewith or incidental thereto.

It is a tool to implement and enforce competition coverage and to prevent and punish anti-competitive business practices by firms and unnecessary Government interference in the market. Competition laws are equally applicable on written as well as oral agreement, arrangements between the organizations or persons.

The competition Act 2002 was formulated with following objectives:

1. To promote healthy competition in the market.

2. To prevent those practices which are having adverse effect on competition.

3. To defend the interests of concerns in a suitable manner.

4. To ensure freedom of alternate in Indian markets.

5. To prevent abuses of dominant position in the market actively.

6. Regulating the operation and activities of combinations (acquisitions, mergers and amalgamation).

7. Creating awareness and imparting training about the competition Act.

Main Features of Competition Act, 2002:

Following are some important features of the competition Act:

1. Competition Act is a very compact and smaller legislation which includes only 66 sections.

2. Competition commission of India (CCI) is constituted under the Act.

3. This Act restricts agreements having adverse effect on competition in India.

4. This Act suitably regulates acquisitions, mergers and amalgamation of enterprises.

5. Under the purview of this Act, the central Government appointed director General for conducting element investigation of anti-competition agreements for arresting CCI.

6. This Act is flexible enough to change its provisions as per needs.

7. Civil courts do not have any jurisdiction to entertain any swimsuit which is within the purview of this Act.

8. This Act possesses penalty provision.

9. Competition Act has replaced MRTP Act.

10. Under this Act, “Competition Fund” has been created.

The Competition Act, 2002 was amended by the Competition (Amendment) Act, 2007 and again by the Competition (Amendment) Act, 2009.

The Competition Act, 2003 gives for the setting up of a Competition Commission of India (CCI) with a view to:

- Prevent practices having adverse effects on competition,

- Curtail abuse of dominance,

- Promote and sustain opposition in market,

- Ensure quality of products and services,

- Protect the interest of buyers and

- Ensure freedom of trade carried on by other participants in home markets.

A subsequent Competition Amendment Bill (2007) seeks to make the CCI function as a regulator and give impetus to factors like:

i. Quality of products and services,

Ii. Healthy competition,

Iii. Faster mergers and acquisitions of companies,

Iv. Regulation of acquisitions and mergers coming inside the threshold limits,

v. Allowing dominance with prevention of its abuse to give effect to the second technology economic reforms on the pattern of the global standards set by using the more developed countries, etc.

i. Anti-Competitive Agreements:

This covers both the horizontal and vertical agreements. It states that four types of horizontal agreements between organisations involved in the same industry would be applied.

These agreements are those that:

(i) lead to fee fixing;

(ii) Limit or control quantities;

(iii) Share or divide markets; and

(iv) Result in bid-rigging.

It also identifies a quantity of vertical agreements subject to review under rule of reach’ test.

Ii. Abuse of Dominance:

The Act lists five classes of abuse:

(i) Imposing unfair/discriminatory conditions in purchase of sale of goods or services (including predatory pricing);

(ii) Limiting or limiting production, or technical or scientific development;

(iii) Denial of market access;

(iv) Making any contract subject to obligations unrelated to the subject of the contract; and

(v) Using a dominant function in one market to enter or protect another.

Iii. Combinations Regulation (Merger and Amalgamation):

The Act states that any combination that exceeds the threshold limits in terms of value of belongings or turnover can be scrutinised by the scrutinised by the CCI to determine whether it will purpose or is likely to cause an appreciable adverse effect on competition within the relevant market in India.

Iv. Enforcement:

The CCI, the authority entrusted with the power to implement the provisions of the Act, can enquire into possibly anti¬competitive agreements or abuse of dominance either on its own initiative or on receipt of a complaint or information from any person, consumer, consumer’s association, a trade association or on a reference by any statutory authority. It can issue ‘cease and desist’ orders and impose penalties. The CCI can also order the break-up of a dominant firm.

The new competition law in India, despite some concerns expressed in sure quarters, is much more consistent with the current anti-trust questioning than the outgoing MRTP Act. Although the success of the new Indian model will now turn on its implementation, India would appear to have taken a very substantial step toward the adoption of a modem competition policy.

On December 16, 2002, the Lok Sabha passed a Bill to replace the MRTP (Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices) Act, 1969 which was enacted to curb the tendency to create monopoly in commerce, trade and industry. The Act is known as Competition Act, 2002 or Antitrust Law.

SUMMARY

Competition Act, 2002

The Competition Act was passed in 2002 and has been amended by way of the Competition (Amendment) Act, 2007. It follows the philosophy of modern competition laws.

O The Act prohibits anti-competitive agreements, abuse of dominant position by firms and regulates combinations (acquisition, acquiring of control and M&A), which causes or possibly to cause an appreciable adverse effect on competition within India.

O In accordance with the provisions of the Amendment Act, the Competition Commission of India and the Competition Appellate Tribunal have been established.

O Government replaced Competition Appellate Tribunal (COMPAT) with the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) in 2017.

.

According to the concerned legislations, the Commission shall consist of a Chairperson and not less than two and not more than ten other Members who shall be appointed by the Central Government.

O the Competition Commission of India is currently functional with a Chairperson and two members.

The commission is a quasi-judicial body which gives opinions to statutory authorities and also deals7with other cases. The Chairperson and other Members shall be whole-time Members.

Eligibility of members: The Chairperson and every other Member shall be a person of ability, integrity and standing and who, has been, or is qualified to be a judge of a High Court, or, has special knowledge of, and professional experience of not less than fifteen years in worldwide trade, economics, business, commerce, law, finance, accountancy, management, industry, public affairs, administration or in any other matter which, in the opinion of the Central Government, may be useful to the Commission

- To remove practices having adverse effect on competition, promote and sustain competition, protect the pastimes of consumers and ensure freedom of trade in the markets of India.

- To give opinion on competition issues on a reference received from a statutory authority established under any regulation and to undertake competition advocacy, create public awareness and impart training on competition issues.

- The Competition Commission of India takes the following measures to obtain its objectives:

- Consumer welfare: To make the markets work for the benefit and welfare of consumers.

- Ensure fair and healthy competition in monetary activities in the country for faster and inclusive growth and development of the economy.

- Implement competition policies with an aim to effectuate the most efficient utilization of monetary resources.

- Develop and nurture effective relations and interactions with sectoral regulators to ensure smooth alignment of sectoral regulatory laws in tandem with the competition law.

- Effectively carry out competition advocacy and spread the statistics on benefits of competition among all stakeholders to establish and nurture competition culture in Indian economy.

- The Competition Commission is India’s competition regulator, and an antitrust watchdog for smaller organizations that are unable to defend themselves in opposition to large corporations.

- CCI has the authority to notify organizations that sell to India if it feels they may be negatively influencing opposition in India’s domestic market.

- The Competition Act guarantees that no enterprise abuses their 'dominant position' in a market through the management of supply, manipulating purchase prices, or adopting practices that deny market access to other competing firms.

- A foreign corporation seeking entry into India through an acquisition or merger will have to abide by the country’s competition laws.

- Assets and turnover above a sure monetary value will bring the group beneath the purview of the Competition Commission of India (CCI).

Section 3 of the Competition Act, 2002

The Act under Section 3(1) prevents any enterprise or association from entering into any agreement which causes or is likely to cause an appreciable adverse effect on competition (AAEC) within India. The Act surely envisages that an agreement which is contravention of Section 3(1) shall be void.

TO DETERMINE AAEC

The Act provides that any agreement which includes cartels, which-

• Directly or indirectly determines purchase or sale prices;

• Limits production, supply, technical development or provision of services in market;

• Results in bid rigging or collusive bidding

Shall be presumed to have an appreciable adverse effect on competition in India

Proviso to Section 3 of the Act offers that the aforesaid criteria shall not apply to joint ventures entered with the aim to extend efficiency in production, supply, distribution, acquisition and control of goods or service.

Anti-competitive agreements are further categorized into Horizontal agreements and Vertical agreements.

Horizontal Agreements

HORIZONTAL AGREEMENTS- Horizontal agreements are arrangements between enterprises at the same stage of production. Section 3(3) of the Act provides that such agreements consists of cartels, engaged in identical or similar trade of goods or provision of services, which-

- Directly or indirectly determines purchase or sale prices

- Limits or controls production, supply

- Shares the market or source of production

- Directly or indirectly results in bid rigging or collusive bidding

Under the Act horizontal agreements are placed in a special category and are subject to the adverse presumption of being anti-competitive. This is also known as ‘per se’ rule. This implies that if there exists a horizontal agreement under Section 3(3) of the Act, then it will be presumed that such an agreement is anti-competitive and has an appreciable adverse effect on competition1.

Vertical Agreements

VERTICAL AGREEMENTS- Vertical agreements are those agreements which are entered into between two or more firms operating at different levels of production.

For instance between supplier and dealers. Other examples of anti-competitive vertical agreements include:

• Exclusive supply agreement & refusal to deal

• Resale price maintenance

• Tie-in-arrangements

• Exclusive distribution agreement

The ‘per se’ rule as applicable for horizontal agreements does not observe for vertical agreements. Hence, a vertical agreement is not per se anti-competitive or does not have an appreciable damaging effect on competition.

The Act under Section 3 of the Act also prohibits any settlement amongst enterprises which materialize in:

• Tie-in arrangement

According to the Statute it includes any agreement requiring purchaser of goods, as a circumstance of purchase, to purchase some other goods. In the case of Sonam Sharma v. Apple & Ors., the CCI stated that in order to have a tying arrangement, the following ingredients need to be present:

- There must be two products that the seller can tie together. Further, there must be a sale or an agreement to sell one product or service on the condition that the buyer purchases the different product or service. In other words, the requirement is that purchase of a commodity is conditioned upon the purchase of another commodity.

- The seller must have sufficient market power with respect to the tying product to extensively restrain free competition in the market for the tied product. That is, the seller has to have such power in the market for the tying product that it can force the buyer to purchase the tied product; and

- The tying arrangement must affect a “not insubstantial” quantity of commerce. Tying arrangements are generally not perceived as being anti- competitive when enormous portion of market is not affected.

• Exclusive supply agreement- The Act defines such agreements to include any agreement restricting in any manner the purchaser in the course of his trade from acquiring or otherwise dealing in any goods other than those of the seller or any other person.

• Exclusive distribution agreement- This includes any agreement to limit, restrict or withhold the output or grant of any goods or allocate any area or market for the disposal or sale of goods.

• Refusal to deal- The Act states that this criteria includes settlement which restricts by any method the persons or classes of individuals to whom the goods are sold or from whom goods are bought.

Shri Shamsher Kataria v. Honda Siel Cars India Ltd. & Ors- Important case law on Anti-competitive Agreements

In the case of Shri Shamsher Kataria v. Honda Siel Cars India Ltd. & Ors3, the thought of vertical agreements including exclusive supply agreements, exclusive distribution agreements and refusal to deal were deliberated by the Commission.

Facts– The informant within the case had alleged anti-competitive practices on a part of the opposite Parties (OPs) whereby the genuine spare parts of automobiles manufactured by a number of the OPs weren't made freely available within the open market and most of the OEMs (original gear suppliers) and therefore the authorized dealers had clauses in their agreements requiring the authorized dealers to provide spare parts only from the OEMs and their authorized vendors only.

CCI’s decision– The Commission held that such agreements are within the nature of exclusive supply, exclusive distribution agreements and refusal to deal under Section 3(4) of the Act and hence the Commission had to make a decision whether such agreements would have an AAEC in India.

The foreign exchange Management Act (FEMA) was an act passed within the winter session of Parliament in 1999, which replaced foreign exchange Regulation Act. This act seeks to form offences associated with foreign exchange civil offences. It extends to the entire of India.

The foreign exchange Regulation Act (FERA) of 1973 in India was replaced on June 2000 by the foreign exchange Management Act (FERA), which was passed in 1999. The FERA was passed in 1973 at a time when there was acute shortage of foreign exchange within the country.

It had a controversial 27 years stint during which many bosses of the Indian corporate world found themselves at the mercy of the Enforcement Directorate. Moreover, any offence under FERA was a criminal offence susceptible to imprisonment. But FEMA makes offences concerning foreign civil offences.

FEMA had become the necessity of the hour to support the pro- liberalisation policies of the govt of India. The objective of the Act is to consolidate and amend the law relating to foreign exchange with the target of facilitating external trade and payments for promoting the orderly development and maintenance of exchange market in India.

FEMA extends to the entire of India. It applies to all or any branches, offices and agencies outside India owned or controlled by an individual , who may be a resident of India and also to any contravention there under committed outside India by two people whom this Act applies.

The Main Features of the FEMA:

The following are a number of the important features of exchange Management Act:

i. It's consistent with full current account convertibility and contains provisions for progressive liberalisation of capital account transactions.

Ii. It's more transparent in its application because it lays down the areas requiring specific permissions of the Reserve Bank/Government of India on acquisition/holding of foreign exchange.

Iii. It classified the foreign exchange transactions in two categories, viz. Capital account and accounting transactions.

Iv. It provides power to the reserve bank for specifying, in , consultation with the central government, the classes of capital account transactions and limits to which exchange is admissible for such transactions.

v. It gives full freedom to an individual resident in India, who was earlier resident outside India, to hold/own/transfer any foreign security/immovable property situated outside India and purchased when s/he was resident.

Vi. This act may be a civil law and therefore the contraventions of the Act provide for arrest only in exceptional cases.

Vii. FEMA doesn't apply to Indian citizen’s resident outside India.

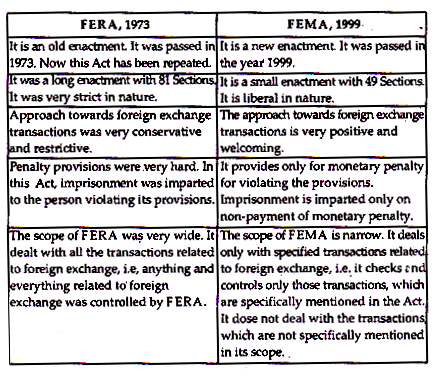

Difference between the FERA and FEMA:

The foreign exchange Management Bill (FEMA) was introduced by the govt of India in Parliament on August 4, 1998. The Bill aims "to consolidate and amend the law concerning foreign exchange with the objective of facilitating external trade and payments and for promoting the orderly development and maintenance of exchange market in India.

Among the varied objectives of the exchange Management Act (FEMA), an important one is to revise and unite all the laws that relate to exchange . Further FEMA targets to market foreign payments and trade the country. Another important motive of the exchange Management Act (FEMA) is to encourage the upkeep and improvement of the foreign exchange market in India.

Features of the FEMA

The following are a number of the important features of foreign exchange Management Act:

a. It's consistent with full current account convertibility and contains provisions for progressive liberalisation of capital account transactions.

b. It's more transparent in its application because it lays down the areas requiring specific permissions of the Reserve Bank/Government of India on acquisition/holding of foreign exchange.

c. It classified the foreign exchange transactions in two categories, viz. Capital account and current account transactions.

d. It provides power to the reserve bank for specifying, in , consultation with the central government, the classes of capital account transactions and limits to which exchange is admissible for such transactions.

e. It gives full freedom to an individual resident in India, who was earlier resident outside India, to hold/own/transfer any foreign security/immovable property situated outside India and purchased when s/he was resident.

f. This act may be a civil law and therefore the contraventions of the Act provide for arrest only in exceptional cases.

g. FEMA doesn't apply to Indian citizen’s resident outside India.

Difference between FERA and FEMA

FEMA: a major Departure from FERA

As is obvious from the name of the Act itself, the emphasis under FEMA is on 'exchange management' whereas under FERA the stress was on 'exchange regulation' or exchange control. Under FERA it had been necessary to get Reserve Bank's permission, either special or general, in respect of most of the regulations there under. FEMA has caused a sea change in this regard and except for Section 3 which relates to dealing in foreign exchange, etc., no other provisions of FEMA stipulate obtaining Reserve Bank's permission.