Unit-6

Economic planning in India

History of India’s Economic Plans:

India gained independence on August 15, 1947, when the country was partitioned. An Industrial Policy Statement was issued in 1948.

It proposed the creation of a National Planning Commission and the formulation of a mixed-economic strategy.

The Constitution went into effect on January 26, 1950. The Planning Commission was formed on March 15, 1950, and the plan period began on April 1, 1951, with the launch of the First Five Year Plan (1951-56).

The concept of economic planning, on the other hand, can be traced back to India's pre-independence days.

“During and after the Great Agricultural Depression, the concept of economic planning gained traction in India (1929-33). The then-Indian government followed a policy of delegating economic matters to individual industrialists and traders.”

(i) 1934:

M. Visvervaraya, an engineer-administrator, is credited with the first blueprints for India's planning. He is credited with being the first to discuss planning in India as a purely economic exercise. In 1934, he suggested a ten-year plan in his book "Planned Economy for India." He proposed a Rs. 1,000 crore capital investment and a six-fold rise in annual industrial production.

(ii) 1938:

The National Planning Committee (NPC) was formed in 1938 by the Indian National Congress, led by Pandit J.L. Nehru, to prepare a plan for economic growth. The NPC was tasked with developing a comprehensive national planning scheme to address issues such as poverty and unemployment, national defence, and economic regeneration in general. The NPC, however, was unable to continue its march after the declaration of World War II in September 1939 and the imprisonment of its leaders.

(iii) 1944:

The Gandhian Plan, the Bombay Plan, and the People's Plan: The Bombay Scheme, devised by Indian capitalists, was one of the most highly debated plans during the 1940s. It was an economic growth initiative involving a significant amount of government action.

It placed a strong focus on the manufacturing sector, with the aim of tripling national output and doubling per capita income in 15 years. The terms "planning" and "industrialization" were used interchangeably in this plan.

M. N. Roy proposed an alternative to the Bombay Plan in 1944. People's Strategy was the name given to his plan. His concept of planning was inspired by Soviet-style planning. Agriculture and small-scale industries were given top priority in this strategy. This proposal favoured a socialist social structure.

S. N. Agarwal wrote ‘The Gandhian Plan' in 1944, based on Gandhian economic concepts, in which he emphasised the expansion of small unit production and agriculture. Decentralization of economic structure of self-contained villages and cottage industries was a key feature.

(iv) 1950 Planning Commission:

The Planning Commission was established by the Government of India in March 1950, shortly after India gained independence. The Commission was given the task of (a) assessing the country's material capital and human resources and formulating a plan for their most effective and balanced utilization; (b) determining priorities, defining the stages for implementing the plan, and proposing resource allocations for the timely completion of each stage; and (c) identifying the factors that tend to stifle economic development.

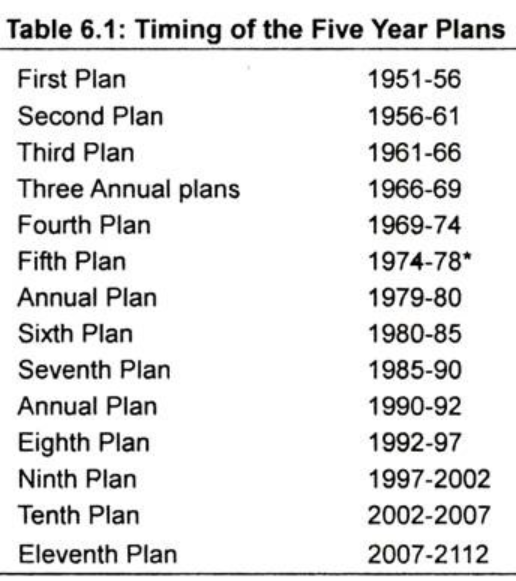

The planning process began in April 1951, with the announcement of the First Five-Year Plan. Ten five-year plans have been completed since then, with the Eleventh Plan in the works.

The Timing of These Eleven Plans are Given here in a Tabular Form:

Characteristics of Indian Plans:

In India, the evolution of economic thought and planning approaches has a long history, and as a result, its characteristics are evolving in tandem with the economy. Every country's structure and goals are never consistent or linear. There is also a significant variation in political perspectives and methods. As a result of these variations, different approaches to planning differ from country to country.

To put it another way, every country has its own economic planning quirks, and India is no exception. Furthermore, Indian planning has a variety of characteristics. It's worth noting that the characteristics refer to the initial situation that shapes planning's future. Again, development goals are not static in the sense that they must be adjusted in response to the country's needs and opportunities.

There are three stages in Indian planning history: pre-independence, 1951-1991, and 1991 and onwards. However, we will focus on the planning of independent India from 1951 to the present. Now we'll go over some of the key features of Indian planning so that you can understand how planning works in both a regulated and planned economy and a market-friendly economy.

1. Five Year Planning:

Despite the fact that India's plans are for a five-year duration, such planning is related to a long-term perspective. The Fourth Five Year Plan was forced to follow a ‘plan holiday' strategy due to the Sino-Indian War (1962), the Indo-Pak War (1965), and the unprecedented drought in the mid-1960s. During the period 1966-1969, instead of a standard Five Year Plan, preparation was replaced by three ad hoc Annual Plans.

With the Janata Government's assumption of power in 1977, a year-to-year rolling programme, or the Sixth Plan, was formulated for the period 1978-83. The Congress (I) government abruptly ended the rolling plan idea in 1980, well ahead of schedule, and the Sixth Plan took effect in 1980 and lasted until 1985. The Eighth Five Year Plan, which was supposed to run from 1990 to 1995, was cancelled due to an unprecedented political crisis in New Delhi and frequent changes of power.

The Eighth Five-Year Plan was postponed by two years, despite the fact that the years 1990-91 and 1991-92 were not scheduled as a "plan holiday." In 1992, the Eighth Five-Year Plan went into effect. There has been no deviation from the five-year planning framework since then.

2. Developmental Planning:

Indian planning is developmental in nature. The country's overall economic growth was given top priority in order to create a self-sufficient economy. Short-term issues such as refugee rehabilitation, food crises, and foreign exchange shortages, on the other hand, received adequate attention from the planners.

3. Comprehensive Planning:

In the sense that it not only implements economic programmes but also emphasises improvements in institutional systems and cultures, Indian planning is systematic. It focuses on agriculture, manufacturing, transportation and communications, as well as physical and social infrastructures such as literacy, health, population control, and the environment. Planning programmes for the advancement of lower castes and backward classes are also underway, with the aim of including these people in the development process.

4. Indicative Planning:

Prior to 1991, Indian planning was primarily directive in nature, with little regard for the position of the market system. When it came to resource allocation in the government sector, the government did not rely on the market but instead issued directives to ensure that resources were used effectively by all states. Private initiative and independence were permitted, but not unrestrictedly. Private industrialists were allowed to invest, but they were also subjected to strict supervision and regulation. Thus, planning in India from 1951 to 1991 was not strictly "planning by course," as in the socialist plan, nor strictly "planning by inducement," as in the capitalist plan.

This old comprehensive method of Indian planning was to be replaced by an integrative approach that combined planning and market mechanisms. With the introduction of the Eighth Five-Year Plan in 1992, Indian planning became indicative in nature. As the plans progress, their speculative existence becomes more apparent.

The government's position becomes passive under it, and the government relinquishes some of its functions at the altar of market principles. It is indicative planning since it merely describes the directions in which the country is supposed to operate and discusses the means by which these goals can be achieved. To increase the economy's performance and competitiveness, dependence on market values is attached, and the planning process then acts as a pathfinder or a leader, rather than placing more focus on the country's long-term objectives.

As a result, one of the most significant characteristics of indicative planning is versatility. Previously, Indian preparation was also indicative of nature. The Eighth Plan, on the other hand, had made it even more so, and had redefined the Planning Commission's role and functions.

5. Democratic Planning:

Planning in India is democratic planning. The Planning Commission is the most important component in establishing the national plan. It is a decision-making body that develops five-year plans and puts them into action in a democratic manner. People's representatives, industrialists, chambers of commerce, educators, and several other bodies, as well as members of the Planning Commission, meet on a regular basis to discuss issues.

The National Development Council is responsible for making planning decisions in collaboration with the federal and state governments. In reality, the NDC is the apex body for coordinating the Central and State Governments' policies and plans.

The proposal paper is presented to Parliament for consideration after receiving the NDC's stamp of approval. Despite the fact that some planning decisions are centralised, Indian planning can be defined as decentralised, if not bottom-up.

6. Decentralised Planning or Planning from Below:

Indian planning is basically a decentralised form of plan since it is democratic. Prior to the Fourth Plan, national planning was simply macro planning. To put it another way, there was little to no allowance for microplanning, or planning from the bottom up. While a "macroplan" offers a broad structure, a "microplan" lays out all of the specifics and establishes goals for various regions based on their unique requirements.

A macroplan would not be able to address the issues of the country's most isolated areas. People are not directly involved in a macroplan. However, for a region's overall development, whether small or large, planning must be decentralised, with local citizens, organisations, and government invited to participate. The term for this is "participatory growth." To deal with local issues, local resources, local goals, and so on, community participation is needed. In this way, the idea of planning from the bottom up rather than the top down has gained traction in India.

7. Present Role of the Planning Commission:

The structure and content of the Eighth Plan (1992-97) differed from previous plans because it was heavily influenced by the government's liberalised economic policies and the evolving global situation. The country gradually shifted away from a very centralised planning structure and toward indicative planning. However, as market forces became more powerful than planning, India's Planning Commission became obsolete. Previously, the Planning Commission operated as a "super-cabinet" in terms of disseminating and executing plan policies and programmes.

As a result of its embrace of business philosophies, the Planning Commission was no longer able to function as a policymaking agency as it once did. In view of recent changes in the Indian situation, the Planning Commission's position must be diluted. To put it another way, the Planning Commission must be wed to the business economy. Most notably, the current UPA government has faced opposition from various sources as a result of coalition politics. And the Planning Commission has been reorganising itself to meet the coalition government's demands.

As a result, Dr. M.S. Ahluwalia stated in relation to the Planning Commission's position that the Planning Commission's two functions are currently more relevant. The first is the position of values, which must be adjusted on a regular basis to meet the needs of the situation. In their policies and values, various ministries will play such a role. Since the respective ministries could not maintain a neutral stance, the Planning Commission would take on a larger position in the realm of perspective or long-term planning. Second, when it comes to long-term planning, the market has very little influence. This is where the Planning Commission comes into play. As a result, the planning methodology must evolve to represent new economic realities and requirements.

As a result, it is clear that the characteristics of Indian planning are not static. The Planning Commission's position has evolved into something new. Above all, the characteristics of Indian plans mentioned above are simply reflections of the country's socio-eco-political ideologies and viewpoints.

Objectives of Indian Plans:

The primary goal of an economic plan in an LDC like India is to bring in new forms of productive capital, which will increase the economy's overall productivity and, as a result, boost people's income by providing them with sufficient job opportunities, thus removing the twin problems of destitution and mass poverty.

1. Economic Growth:

The goal of economic development has earned the highest priority of all the goals in all of the programmes. India's economic planning aims to achieve accelerated economic growth in all fields. Agriculture, electricity, industry, and transportation are the most important sectors.

The country aims to raise national and per capita incomes through economic growth. As a result, poverty will be eradicated and people's living standards will be raised. During the First Plan, national income rose by 18 percent, above the targeted growth rate of 11 percent.

During the Second Plan era, national income increased by 20%, against a goal of 21%. Per capita income, on the other hand, increased at a rate of 2.1 percent per year, against a projected rate of 3.3 percent. The Third Plan aimed to boost national income by 5.6 percent a year. However, according to the Third Plan's progress report, national income rose by just 2.5 percent per year. During this time, per capita income did not increase.

The Fourth Plan aimed for annual growth rates of 5.7 percent and 3 percent for national income and per capita income, respectively. In fact, national income increased by only 3.4 percent, while per capita income increased by only 1.1 percent. The Fifth Plan introduced a 3.5 percent annual growth rate, which was later changed to 4.37 percent.

However, the economy is now doing well, with an annual growth rate of 5.2 percent. The Sixth Plan aimed for a 5.2 percent annual growth rate. This rate of growth was actually accomplished. The annual growth rate of the Seventh Plan (1985-1990) was 6%. The Eighth Plan had a higher average growth rate (6.8%) than the Seventh Plan. In the Ninth Plan, this growth rate fell to 5.4 percent, compared to a target of 6.5 percent. A objective of 8% is a lofty goal. In the tenth five-year plan, the GDP growth rate was reached.

2. Economic Equality and Social Justice:

The twin facets of social justice are the reduction of economic inequality on the one hand, and the reduction of poverty on the other.

It is undesirable to see national income grow as economic power is concentrated in the hands of a few citizens. There are vast disparities in India's socio-political structure. Indian policies seek to reduce inequality such that the benefits of economic growth reach the poorest members of society.

For the first time, the goal of eradicating poverty was stated explicitly in the Fifth Plan. Economic disparities widened and poverty became widespread as a result of the flawed planning strategy. Poverty was becoming more prevalent.

In light of this perplexing growth, the slogan "Garibi Hatao" was raised for the first time in the Fifth Plan. In 1974, it was estimated that about 30% of the total population lived in poverty. In 1983-84, 44.5 percent of the population was living in poverty. By 1993-94, it had dropped to 37.3 percent. According to the most recent survey, 28.3 percent of the population lived below the poverty line in 2004-05.

Despite the fact that the poverty rate decreased over time, the number of poor people remained at more than 260 million in 1999-2000 due to population growth.

3. Full Employment:The elimination of unemployment is another critical goal of India's Five Year Plans. Unfortunately, it was never given the attention it deserved. For the first time, jobs was given pride of place in the Janata Government's Sixth Plan (1978-83). The Seventh Plan, on the other hand, prioritised jobs as a policy priority. As a result, India's job creation programme has been severely hampered, and the issue of unemployment continues to worsen.

4. Economic Self-Reliance:

The term "self-reliance," or "self-sufficiency," refers to the lack of reliance on others. To put it another way, it means no international assistance. India is known for being a reliant economy. She is accustomed to bringing in large quantities of food crops, fertilisers, raw materials, and heavy machinery and equipment. However, prior to the start of the Fourth Plan, this goal could not be coordinated.

The Fifth Plan's main goal was to achieve self-sufficiency. To accomplish this, the Fifth Plan aimed to boost production of food grains, essential consumer products, and raw materials, as well as exports. While the Plan emphasised increased exports, it also stressed the importance of developing import substitution industries as an essential aspect of economic self-reliance.

The goal of self-reliance lost its previous interpretation in the new age, which began in July 1991. In today's globalised world, it no longer applies to self-sufficiency. Even then, it remains an important part of India's growth strategy.

5. Modernisation:

This goal is a little newer than the others. This goal was discussed explicitly for the first time in the Sixth Plan. Modernisation refers to a wide range of systemic and institutional changes in the economy that can turn a feudal or colonial economy into a democratic and liberal one.

The creation of a diversified economy that produces a variety of products is an essential component of modernisation. This necessitates the establishment of a number of industries. It may also refer to a technological development. Certain technological advancements have undoubtedly occurred in agriculture, oil, and other fields. However, in the current situation, this goal is in grave danger.

The nation is now dealing with an alarmingly high rate of unemployment and, as a result, poverty. Modernisation, on the other hand, would undoubtedly halt the development of jobs. As a result, there is a tension between the goals of modernisation and eradicating unemployment and poverty.

Aside from these long-term goals, each Five-Year Plan in India has a set of short-term goals. For example, the First Plan prioritised agricultural production, inflation control, and refugee rehabilitation. The Second Plan was designed to promote rapid industrial development, especially in the basic and heavy industries. The Third Plan emphasised basic industry expansion but shifted its focus to defence production.

Evaluation of Objectives:

The goals of Indian planning are very broad, and its reach is quite wide.

However, it has a number of flaws:

(a) First and foremost, the Indian plans are ambitious. The majority of the plan's priorities are yet to be met. Some of the goals aren't quantifiable, and the expected outcomes never line up with the real outcomes. The real results were hidden behind the goals.

(b) Second, the targets that are set in Indian plans are inconsistent. For example, the goal of capital accumulation is incompatible with the goal of reducing income inequality.

(c) Finally, there are goals that are at odds. The goal of higher economic growth may not be compatible with the goal of creating jobs. Rapid economic growth necessitates the application of capital-intensive technology, which is labor-displacing by definition. As a result, any effort to increase GDP growth rate is likely to sabotage the goal of eliminating unemployment.

Despite these flaws in Indian planning, we must admit that the primary goal of increased economic development is the most important of all. The plan's goals must be spelled out in such a way that they are in line with the country's needs.

Key takeaway:

1) India's first five-year plan, launched in 1951, centred on agriculture and irrigation to increase farm productivity as the country's foreign reserves were being depleted by foodgrain imports. It was based on the Harrod-Domar model, which aimed to improve economic growth by encouraging people to save and spend more.

2) The rate of capital creation in India has increased as agriculture, industry, and defence have grown. The rate of capital accumulation was 11.0 percent in 1950-51, but it jumped to 21.3 percent in 2000-01.

References-