UNIT-5

WAVE OPTICS

5.1.1 DIFFRACTION: INTRODUCTION

When the light falls on the obstacle whose size is comparable with the wavelength of light then the light bends around the obstacle and enters the geometrical shadow. This bending of light is called diffraction.

Diffraction is the light bending of light as it passes around the edge of an object. The amount of bending depends on the relative size of the wavelength of light to the size of the opening. If the opening is much larger than the light’s wavelength, the bending will be almost unnoticeable. However, if the two are closer in size or equal, the amount of bending is considerable, and easily seen with the naked eye.

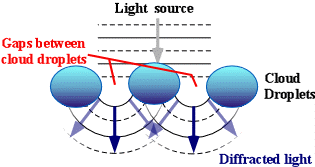

Figure 1: Diffraction of light

In the atmosphere, diffracted light is bent around atmospheric particles – most commonly, the atmospheric particles are tiny water droplets found in clouds. Diffracted light can produce fringes of light, dark or colored bands. An optical effect that results from the diffraction of light is the silver lining sometimes found around the edges of clouds or coronas surrounding the sun or moon. The illustration above shows how light (from either the sun or the moon) is bent around small droplets in the cloud.

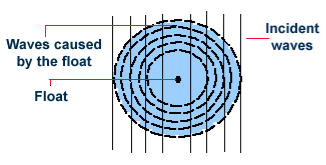

Optical effects resulting from diffraction are produced through the interference of light waves. To visualize this, imagine light waves like water waves. If water waves were incident upon a float residing on the water surface, the float would bounce up and down in response to the incident waves, producing waves of their own. As these waves spread outward in all directions from the float, they interact with other water waves. If the crests of two waves combine, an amplified wave is produced (constructive interference). However, if a crest of one wave and a trough of another wave combine, they cancel each other out to produce no vertical displacement (destructive interference).

Figure 2: Diffraction

This concept also applies to light waves. When sunlight (or moonlight) encounters a cloud droplet, light waves are altered and similarly interact with one another as the water waves described above. If there is constructive interference, (the crests of two light waves combining), the light will appear brighter. If there is destructive interference, (the trough of one light wave meeting the crest of another), the light will either appear darker or disappear entirely.

Types of Diffraction

There are two types of diffractions

- Fresnel Diffraction: Fresnel diffraction is produced when light from a point source meets an obstacle, the waves are spherical and the pattern observed is a fringed image of the object.

- Fraunhofer Diffraction: Fraunhofer diffraction occurs with plane wave-fronts with the object effectively at infinity. The pattern is in a particular direction and is a fringed image of the source.

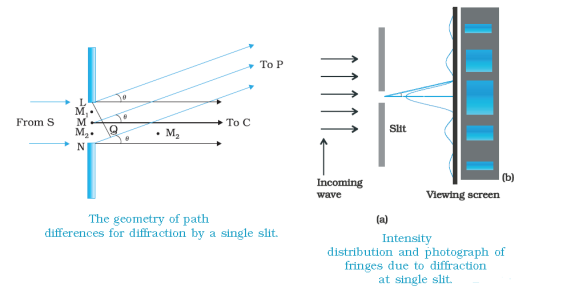

Figure 3: Types of diffractions Fresnel Diffraction & Fraunhofer Diffraction

From the above figure, we observe that the source is located at a finite distance from the slit, and the screen is also at a finite distance from the slit. The source and the screen are not very far from each other. So this is Fresnel diffraction. Here, if suppose the ray of light comes exactly at the edge of the obstacles, the path of the light is changed. So the light bends a little and meets the screen.

A beam of width α travels a distance of α2/λ, called the Fresnel distance before it starts to spread out due to diffraction. But when the source and the screen are far away from each other, and when the source is located at the infinite position, then the ray of light coming from that infinite source are parallel rays of light. So this is Fraunhofer diffraction.

Here we have to make use of the lens. But why do we use the lens? Because in Fraunhofer diffraction, the source is at infinity so the rays of light that pass through the slit are parallel rays of light.

So to make these rays parallel to focus on the screen, we, make use of the converging lens. The zone which we get in front of the slit in the central maxima. On either side of the central maxima, there is a bright zone i.e. 1st maxima.

Comparison

Fresnel Diffraction | Fraunhofer diffraction |

1 If the source of light and screen is at a finite distance from the obstacle, then the diffraction is called Fresnel diffraction. | 1 If the source of light and screen is at an infinite distance from the obstacle then the diffraction is called Fraunhofer diffraction. |

2 The corresponding rays are not parallel. | 2 The corresponding rays are not parallel. |

3 The wavefronts falling on the obstacle are not plane. | 3 The wavefronts falling on the obstacle are planes. |

4 No convex lens is needed to converge spherical wavefronts. | 4 Plane diffracting wavefronts are converged by means of a convex lens to produce a diffraction pattern. |

5 Fresnel diffraction patterns on flat surfaces. | 5 Fraunhofer diffraction patterns on spherical surfaces. |

6 Diffraction patterns Change as we propagate them further ‘downstream’ of the source of scattering. | 6 Diffraction patterns Shape and intensity of a Fraunhofer diffraction pattern stay constant. |

7 To obtain Fresnel diffraction, zone plates are used. | 7 To obtain Fraunhofer diffraction, the single-double plane diffraction grafting is used. |

8 Diffraction pattern moves along the corresponding shift in the object. | 8 Diffraction pattern remains in a fixed position. |

Key Takeaways

- When the light falls on the obstacle whose size is comparable with the wavelength of light then the light bends around the obstacle and enters the geometrical shadow. This bending of light is called diffraction.

- There are two types of diffractions Fresnel Diffraction & Fraunhofer Diffraction

- Fresnel diffraction is produced when light from a point source meets an obstacle, the waves are spherical and the pattern observed is a fringed image of the object.

- Fraunhofer diffraction occurs with plane wave-fronts with the object effectively at infinity. The pattern is in a particular direction and is a fringed image of the source.

- Huygens’ Principle states that every point on a wavefront is a source of wavelets that spread out in the forward direction at the same speed as the wave itself. The new wavefront is a line tangent to all of the wavelets.

5.1.2 RESOLVING POWER, RAYLEIGH CRITERION,

Limit of Resolution:

The minimum distance between two points on the object so that their images (as produced by the optical instrument) are just seen as separate from each other is called limit of resolution of the optical instrument.

Statement: Two sources are resolvable by an optical instrument when the central maximum of one diffraction pattern falls over the first minimum of the other diffraction pattern and vice versa.

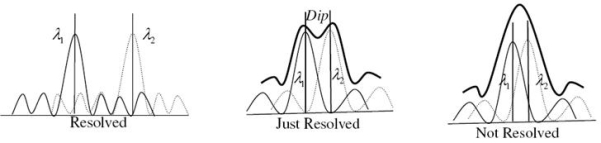

Let us consider the resolution of two wavelengths by a grating. When the difference in wavelengths is smaller and such that the central maximum of the wavelength coincides with the first minimum of the other as shown in figure, then the resultant intensity curve is as shown by the thick curve. The curve shows a distinct dip in the middle of two central maxima. Thus the two wavelengths can be distinguished from one another and according to Rayleigh they are said to be “Just Resolved”.

If the difference in wavelengths is such that their principal maxima are separately visible, then there is a distinct point of zero intensity in between the two wavelengths. Hence according to Rayleigh they are said to be “Resolved”.

When the difference in wavelengths is so small that the central maxima corresponding to two wavelengths come still closer as shown in figure, then the resultant intensity curve is quite smooth without any dip. This curve is as if there is only one wavelength somewhat bigger and stronger.

Hence according to Rayleigh the two wavelengths are “Not Resolved”.

Thus the two spectral lines can be resolved only up to a certain limit expressed by Rayleigh Criterion.

Figure 4: Rayleigh Criterion

5.1.3 THEORY OF DIFFRACTION GRATING

A set of a large number of parallel slits of the same width and separated by opaque spaces is known as a diffraction grating.

Diffraction gratings are much more effective than prisms for dispersing light of different wavelengths so they are used almost exclusively in instruments designed to detect and identify characteristic spectral lines. There is nothing mysterious about these devices.

Fraunhofer used the first grating consisting of a large number of parallel wires placed side by side very closely at regular separation. Now the gratings are constructed by ruling the equidistance parallel lines on a transparent material such as glass with a fine diamond point. The ruled lines are opaque to light while the space between the two lines is transparent to light and acts as a slit.

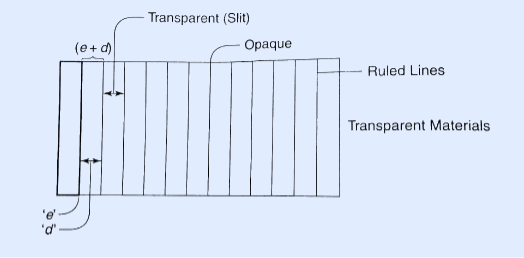

Figure 5: Plane Transmission Grating

Let ‘e’ be the width of the line and ‘d’ be the width of the slit.

Then (e + d) is known as the grating element.

If N is the number of lines per inch on the grating then

(𝑒+𝑑)=1𝑖𝑐ℎ=2.54𝑐𝑚

(𝑒+𝑑)=2.54𝑐𝑚/𝑁

Commercial gratings are produced by taking the cost of actual grating on a transparent film like that of cellulose acetate. The solution of cellulose acetate is poured on a ruled surface and allowed to dry to form a thin film, detachable from the surface. This film of the grating is kept between the two glass plates.

DISPERSIVE POWER OF GRATING

Dispersive power of a grating is defined as the ratio of the difference in the angle of diffraction of any two neighbouring spectral lines to the difference in the wavelength between the two spectral lines.

Or

It can also be defined as the diffraction in the angle of diffraction per unit change in wavelength.

The diffraction of the nth order principal maximum for a wavelength λ is given by the equation,

(a + b) sin θ = nλ (1)

Differentiating this equation with respect to θ and λ

a + b is constant and n is constant in a given order.

(a + b) cos θ dθ = n dλ

(2)

(2)

In equation (2) dθ/dλ is the dispersive power,

n is the order of the spectrum,

N’ is the number of lines per cm of the grating surface and

θ is the angle of diffraction for the nth order principal maximum of wavelength λ.

From equation (2), it is clear, that the dispersive power of the grating is directly proportional to the number of lines per cm and inversely proportional to cos θ.

Thus, the angular spacing of any two spectral lines is double in the second-order spectrum in comparison to the first order. Secondly, the angular dispersion of the lines is more with a grating having a larger number of lines per cm. Thirdly, the angular dispersion is minimum when θ = 0. If the value of θ is not large the value of cosθ can be taken as unity approximately and the influence of the factor cosθ in the equation (2) can be neglected.

Neglecting the influence of cosθ, it is clear that the angular dispersion of any two spectral lines (in a particular order) is directly proportional to the difference in wavelength between the two spectral lines. A spectrum of this type is called a normal spectrum.

If the linear spacing of two spectral lines of wavelength λ and λ + dλ is dx in the focal plane of the telescope objective or the photographic plate, then,

Dx = fdθ

Where ƒ is the focal length of the objective. The linear dispersion

The linear dispersion is useful in studying the photographs of a spectrum.

Key Takeaways

- A set of a large number of parallel slits of the same width and separated by opaque spaces is known as a diffraction grating.

- Dispersive power of a grating is defined as the ratio of the difference in the angle of diffraction of any two neighbouring spectral lines to the difference in the wavelength between the two spectral lines.

- dθ/dλ is the dispersive power is given by

5.1.4 RESOLVING POWER.

Resolving power of diffraction grating

It is defined as the capacity of a grating to form separate diffraction maxima of two wavelengths that are very close to each other

It is measured by λ/dλ where dλ is the smallest difference in two wavelengths which are just resolvable by grating and λ is the wavelength of either of them or mean wavelength.

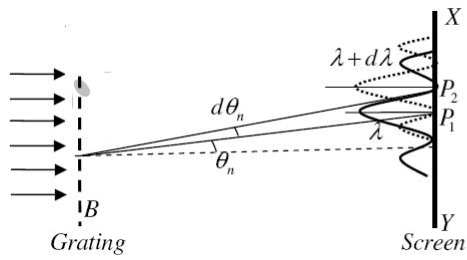

Figure 6: Resolving Power of Diffraction Grating

Let AB represent the surface of a plane transmission grating having grating element (e+d) and N total number of slits.

Let a beam of light having two wavelengths by λ and dλ is normally incident on the grating. Let P1 is an nth primary maximum of a spectral line of wavelength λ at an angle of diffraction  and P2 is the nth primary maximum of wavelength λ+dλ at diffracting angle θ+dθ.

and P2 is the nth primary maximum of wavelength λ+dλ at diffracting angle θ+dθ.

According to the Rayleigh criterion, the two wavelengths will be resolved if the principal maximum λ+dλ of nth order in a direction θ+dθ falls over the first minimum of nth order in the same direction θ+dθ.

Let us consider the first minimum of l of nth order in the direction θ+dθ as below.

The principal maximum of  in the θ direction is given by

in the θ direction is given by

(e+d)sinθ =nλ ………………(1)

The equation of minima is

N(e+d)sinθ = mλ ………………(2)

Where m takes all integers except 0, N, 2N, …, nN, because, for these values of m, the condition for maxima is satisfied.

Thus first minimum adjacent to the nth principal maximum in the direction θ+dθ can be obtained by substituting the value of ‘m’ as (nN+1).

Therefore, the first minimum in the direction of θ+dθ is given by

N(e+d)sin(θ+dθ) = (nN+1)λ

(e+d)sin(θ+dθ) = (n+ )λ ………………(3)

)λ ………………(3)

The principal maximum of λ+dλ in direction θ+dθ is given by

(e+d)sin(θ+dθ) = n(λ+dλ) ………………(4)

Dividing eqn(3) by equation (4), we get

(n+ )λ = n(λ+dλ)

)λ = n(λ+dλ)

nλ + = nλ + ndλ

= nλ + ndλ

= ndλ

= ndλ

= nN

= nN

Resolving Power =  = nN ………………(5)

= nN ………………(5)

Thus the resolving power is directly proportional to

(i) The order of the spectrum ‘n’

(ii) The total number of lines on the grating ‘N

Key Takeaways

- It is defined as the capacity of a grating to form separate diffraction maxima of two wavelengths that are very close to each other

- Resolving Power =

= nN

= nN

POLARIZATION

The phenomena of interference and diffraction confirm the wave nature of light hence neither of these phenomena is able to indentify the nature of waves that light is. These phenomena do not tell whether the oscillation of light waves are longitudinal or transverse in nature. This is accompalished by the study of polarization.

A light wave that is vibrating in more than one plane is referred to as unpolarized light.

Example: Light emitted by the sun, by a lamp in the classroom, or by a candle flame is unpolarized light.

These unpolarized light is created by electric charges that vibrate in a variety of directions, this concept of unpolarized light is difficult to visualize. For simplicity it is helpful to visualize unpolarized light as a wave that has an average of half its vibrations in a horizontal plane and half of its vibrations in a vertical plane. It is possible to transform unpolarized light into polarized light.

Polarized light waves are light waves in which the vibrations occur in a single plane. The process of transforming unpolarized light into polarized light is known as polarization.

Figure 7: Polarization.

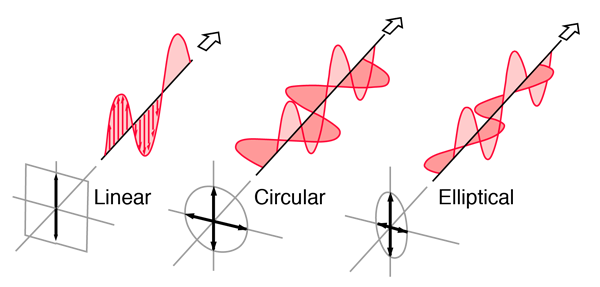

Classification of light

Light in the form of a plane wave in space is said to be linearly polarized. Light is a transverse electromagnetic wave, but natural light is generally unpolarized, all planes of propagation being equally probable. If light is composed of two plane waves of equal amplitude by differing in phase by 90°, then the light is said to be circularly polarized. If two plane waves of differing amplitude are related in phase by 90°, or if the relative phase is other than 90° then the light is said to be elliptically polarized.

Linearly Polarized: Light in the form of a plane wave in space is said to be linearly polarized. The electric field of light is limited to a single plane along the direction of propagation.

Circularly Polarized If light is composed of two plane waves of equal amplitude by differing in phase by 90°, then the light is said to be circularly polarized. If the thumb of your right hand were pointing in the direction of propagation of the light, the electric vector would be rotating in the direction of your fingers.

Elliptically Polarized If two plane waves of differing amplitude are related in phase by 90°, or if the relative phase is other than 90° then the light is said to be elliptically polarized. If the thumb of your right hand were pointing in the direction of propagation of the light, the electric vector would be rotating in the direction of your fingers.

Figure 8: Showimg Linear, Circular and Elliptical Polarization

POLARIZATION BY REFLECTION

Production of Polarized Light by Reflection

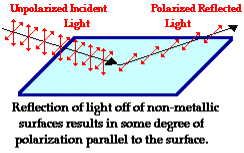

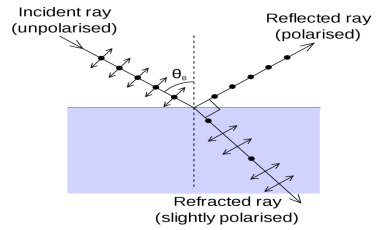

The Brewster’s law can be used to polarise the light by reflection. When unpolarised light is incident on the boundary between two transparent media, the reflected light is polarised with its electric vector perpendicular to the plane of incidence when the refracted and reflected rays make a right angle with each other.

Figure 9: Production of Polarized Light by Reflection

Thus we have seen that when reflected wave is perpendicular to the refracted wave, the reflected wave is a totally polarised wave. The electric field vectors of all unpolarized light may be resolved into two components as follows;

- Tangential component- in the plane of incidence.

- Normal components – in the plane perpendicular to plane of incidence.

The angle of incidence in this case is called Brewster’s angle

Figure 10: Reflection and refraction

If the angle of incidence θi is varied, the reflected coefficient ‘r’ for the em waves corresponding to the tangential component will vary as shown in figure. As θi increases r will decrease.

At θi = Brewster angle (about 57° for glass) r will be zero and no reflection of the tangential component will take place.

The reflected beam will contain light waves having only the normal component for the electric field as shown in figure that is the reflected light will be plane polorized with the oscillations of electric field vector normal to the plane of incidence.

Cause of Polrizaton by Reflection

The em waves are generated because of the oscillation of electric charge. The electric field vectors of the transmitted ray act on the electrons in the dielectric.

Since the intensity of em wave emitted by the oscillating charge is maximum in a direction normal to the plane of oscillation, and zero along the line of oscillations for the plane polarized light having electric field vector in the plane of incidence, there will be no emition of em waves in a direction normal to the reflected ray. In figre the direction along which no emission should accur is called as zero intensity line. Let the angle between the reflected ray and the zero intensity line be 𝛿 the angle between the reflected and tranmitted ray is π/2 + 𝛿 suppose we arrange the angle of incidence such that

n=sinθi / sinθr

n=sinθi / sin(π/2 – θi)

n=sinθi / cosθi

n=tan θi

That is possible when

θi + θr = π/2 according to Brewster’s law

From figure

θi + θr+ π/2 + = π

As θi + θr = π/2

So π/2+ π/2 + = π

= 0

The line of zero intensity and the refected ray will coincide. Thuse there will be no reflection of light when the angle of incidence is equal to Brewster’s angle.

Thus the unpolarized light can be polarized by reflection as the reflected beam will contain light waves having electric field vector oscilating along normal to the plane of the incidence only.

PRODUCTION OF POLARIZED LIGHT BY REFRACTION

Polarization can also occur by the refraction of light. Refraction occurs when a beam of light passes from one material into another material. At the surface of the two materials, the path of the beam changes its direction. The refracted beam acquires some degree of polarization.

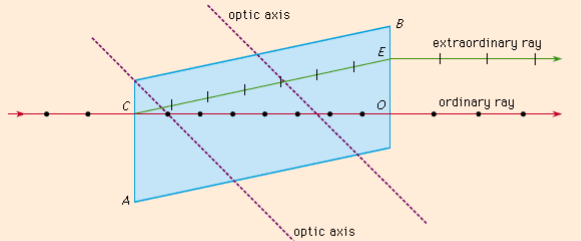

Birefringence, an optical property in which a single ray of unpolarized light entering an anisotropic medium is split into two rays, each traveling in a different direction. One ray (called the extraordinary ray) is bent, or refracted, at an angle as it travels through the medium; the other ray (called the ordinary ray) passes through the medium unchanged.

The ordinary ray and the extraordinary ray are polarized in planes vibrating at right angles to each other. The refractive index of the ordinary ray is constant in all directions; the refractive index of the extraordinary ray varies according to the direction because it has components that are both parallel and perpendicular to the crystal’s optic axis. An extraordinary ray can move either faster or slower than an ordinary ray.

Figure 11: production of polarized light by refraction

The Figure shows the phenomenon of double refraction through a calcite crystal. An incident ray is seen to split into the ordinary ray CO and the extraordinary ray CE upon entering the crystal face at C. If the incident ray enters the crystal along the direction of its optic axis, however, the light ray will not become divided.

The polarization occurs in a plane perpendicular to the surface. The polarization of refracted light is demonstrated by a unique crystal that serves as a double-refracting crystal.

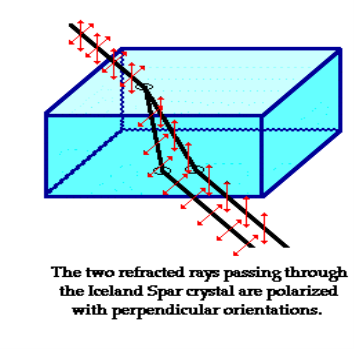

Iceland Spar (calcite mineral), refracts incident light into two different paths. The light is split into two beams upon entering the crystal.

Figure 12: Refracted rays passing through Iceland spar crystal

That mean if we see an object through an Iceland spar crystal, two images will observed. These two images are the result of the double refraction of light. Both refracted light beams are polarized - one in a direction parallel to the surface and the other in a direction perpendicular to the surface

Since these two refracted rays are polarized with a perpendicular orientation, a polarizing filter can be used to completely block one of the images. If the polarization axis of the filter is aligned perpendicular to the plane of polarized light, the light is completely blocked by the filter; meanwhile the second image is as bright as can be. And if the filter is then turned 90-degrees in either direction, the second image reappears and the first image disappears.

Negative and Positive Crystals:

Suppose vo and ve be the velocities of the ordinary and extraordinary rays. The crystals in which vo<ve are termed as negative and in which vo>ve are termed as positive. Calcite is negative crystal and quartz is an example of positive crystal.

Uniaxial and Biaxial crystals:

Uniaxial crystal: A crystal which has only one optic axis is called uniaxial crystal. The refractive index of the ordinary ray is constant for any direction in the crystal. Examples:- Calcite, Quartz, Ice, Tourmaline etc.

Biaxial crystal: A crystal which has only two optic axis is called biaxial crystal. The refractive index of the extraordinary ray is variable and depends on the direction. Examples:- Mica, Topaz, Borax etc.

All transparent crystals except those of the cubic system, which are normally optically isotropic, exhibit the phenomenon of double refraction: in addition to calcite, some well-known examples are ice, mica, quartz, sugar, and tourmaline. Other materials may become birefringent under special circumstances.

For example, solutions containing long-chain molecules exhibit double refraction when they flow; this phenomenon is called streaming birefringence. Some isotropic materials like glass may even exhibit birefringence when placed in a magnetic or electric field or when subjected to external stress.

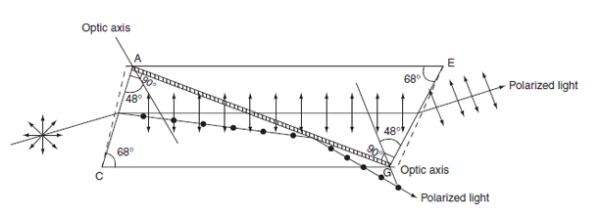

DOUBLE REFRACTION BY NICOL PRISM

This was invented by William Nicol in the year 1828. Nicol prism is made from a double refracting calcite crystal.

A Nicol Prism is a type of polarizer, an optical device used to produce a polarized beam of light.

It is made in such a way that it eliminates one of the rays by total internal reflection, i.e. the ordinary ray is eliminated and only the extraordinary ray is transmitted through the prism.

Construction of Nicol prism:

- Length of calcite crystal is three times its breath.

- The corners A′G′ is blunt and A′C G′E is the principal section with ∠A′CG′ = 71°.

- The end faces A′BCD and EFG′H are grounded so that the angle ACG = 68°.

- The crystal is cut along the plane AKGL. The cut surfaces are polished until they are optically flat and cemented together with Canada balsam.

The refractive index of Canada balsam (1.55) is in between the refractive indices of ordinary (1.658) and extraordinary (1.486) rays in calcite crystal.

Figure 13: Production of plane polarized light using Nicol prism

Figure 13: Production of plane polarized light using Nicol prism

Working

- The diagonal AG represents the Canada balsam layer.

- A beam of unpolarized light is incident parallel to the lower edge on the face ABCD.

- The ray gets doubly refracted on entering into the crystal.

- From the refractive index values, we know that the Canada balsam acts as a rarer medium for the ordinary ray and it acts as a denser medium for extraordinary ray.

- When the angle of incidence for ordinary ray on the Canada balsam is greater than the critical angle then total internal reflection takes place, while the exaordinary ray gets transmitted through the prism.

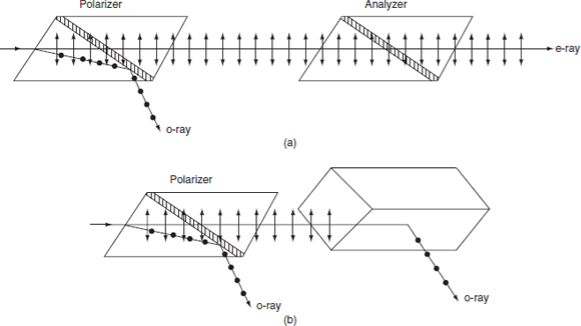

- Nicol prism can be used as an analyser.

Figure 14: (a) Parallel Nicols; (b) Crossed Nicols

- Two nicol prisms are placed adjacently as shown in figure.

- One prism acts as a polarizer and the other act as an analyzer.

- The exaordinary ray passes through both the prisms.

- If the second prism is slowly rotated, then the intensity of the exaordinary ray decreases.

- When they are crossed, no light come out of the second prism because the e-ray that comes out from first prism will enter into the second prism and act as an ordinary ray. So, this light is reflected in the second prism. The first prism is the polarizer and the second one is the analyser.

Difference between Positive Crystal and Negative Crystal

Positive Crystal | Negative Crystal |

|

|

2. The crystals in which vo>ve are termed as positive. In positive crystals E-ray travels slower than o-ray in all directions except along the optic axis. | 2. The crystals in which vo<ve are termed as negative. In negative crystals O-ray travels slower than E- ray in all directions except along the optic axis. |

3. According to Huygen's ellipse corresponding to e-ray is contained within the sphere corresponding to o-ray | 3. According to Huygen's ellipse corresponding to e-ray lies outside the sphere corresponding to O-ray |

4. Birefringence or amount of double refraction of a crystal is defined as ∆μ=μe-.μ for ∆μ is positive quality for positive crystals. | 4. ∆μ Negative for negative crystals. |

5. Example:Quartz | 5. Example :calcite |

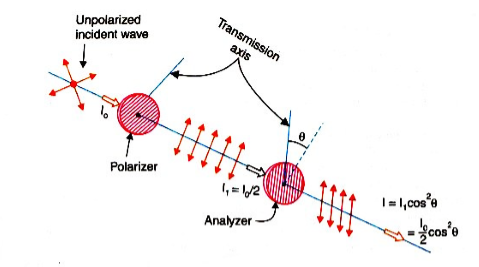

MALUS LAW

Plane polarized light is obtained by passing unpolarized light through a polarizer. When plane polarized light from the polarizer is passed through the analyser, the intensity of polarised light transmitted through the analyser varies as the square of the cosine of the angle between the plane of transmission of the analyser and the plane of the polarizer. This is known as Malus law.

It states that "The intensity of the polarized light transmitted through the analyser is proportional to cosine square of the angle between the plane of transmission of the analyser and plane of transmission of the polarizer."

Figure 15: Malus law

Let I0 is the intensity of unpolarized light. The intensity of polarized light from the polarizer is I0/2.

Take I1=I0/2. This plane polarized light then passes through the analyser. Let E is the aptitude of vibration and θ is the angle between this vibration and transmission axis of an analyser.

E resolves into two components

(i) Ey parallel to the plane of transmission of the plane of analyser and

(ii) Ex perpendicular to the plane of analyser.

Now, Ey component is only transmitted through the analyser.

Ey = Ecosθ

Intensity of light for this component:

I = E2cos2θ = I1 cos2θ = I0/2 cos2θ

If, (i) θ = 0°, then axis are parallel I= I1

(ii) θ = 90°, then axis are perpendicular I= 0

(iii) θ = 180°, then axis are parallel I= I1

(iv) θ= 270°, then axis are perpendicular I= 0

Thus, there are two positions of maximum intensity and two positions of zero intensity when we rotate the axis of the analyser with respect to that of the polarizer.

Key Takeaways

- Polarized light waves are light waves in which the vibrations occur in a single plane. The process of transforming unpolarized light into polarized light is known as polarization.

- Classification of light (i) linearly polarized. (ii)circularly polarized (iii) elliptically polarized.

- The Brewster’s law can be used to polarise the light by reflection.

- Birefringence, an optical property in which a single ray of unpolarized light entering an anisotropic medium is split into two rays, each traveling in a different direction. One ray (called the extraordinary ray) is bent, or refracted, at an angle as it travels through the medium; the other ray (called the ordinary ray) passes through the medium unchanged.

- Nicol prism is made from a double refracting calcite crystal.

- A Nicol Prism is a type of polarizer, an optical device used to produce a polarized beam of light.

- Suppose vo and ve be the velocities of the ordinary and extraordinary rays. The crystals in which vo<ve are termed as negative and in which vo>ve are termed as positive. Calcite is negative crystal and quartz is an example of positive crystal.

- Malus Law states that "The intensity of the polarized light transmitted through the analyser is proportional to cosine square of the angle between the plane of transmission of the analyser and plane of transmission of the polarizer."

5.3.1 OPTICAL ACTIVITY, SPECIFIC ROTATION

Optical Activity

The optical activity was first observed in quartz crystals in 1811 by a French physicist, François Arago. Louis Pasteur was the first to recognize that optical activity arises from the dissymmetric arrangement of atoms in the crystalline structures or in individual molecules of certain compounds.

Optical activity, the ability of a substance to rotate the plane of polarization of a beam of light that is passed through it. (In plane-polarized light, the vibrations of the electric field are confined to a single plane.

The intensity of optical activity is expressed in terms of a quantity, called specific rotation, defined by an equation that relates the angle through which the plane is rotated, the length of the light path through the sample, and the density of the sample (or its concentration if it is present in a solution). Because the specific rotation depends upon the temperature and upon the wavelength of the light, these quantities also must be specified. The rotation is assigned a positive value if it is clockwise with respect to an observer facing the light source, negative if counterclockwise. A substance with a positive specific rotation is described as dextrorotatory and denoted by the prefix d or (+); one with a negative specific rotation is levorotatory, designated by the prefix l or (-).

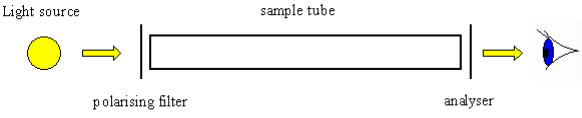

Optical activity is the ability of a chiral molecule to rotate the plane of plane-polarised light, measured using a polarimeter. A simple polarimeter consists of a light source, polarising lens, sample tube, and analyzing lens.

Figure 16: Polarimeter

When light passes through a sample that can rotate plane polarised light, the light appears to dim because it no longer passes straight through the polarising filters. The amount of rotation is quantified as the number of degrees that the analyzing lens must be rotated by so that it appears as if no dimming of the light has occurred.

Measuring Optical Activity

When rotation is quantified using a polarimeter it is known as an observed rotation, because rotation is affected by path length (l, the time the light travels through a sample) and concentration (c, how much of the sample is present that will rotate the light). When these effects are eliminated a standard for comparison of all molecules is obtained, the specific rotation, [a].

[a] = 100a / cl when concentration is expressed as g sample /100ml solution

Enantiomers will rotate the plane of polarisation in exactly equal amounts (same magnitude) but in opposite directions.

As already discussed Dextrorotary designated as d or (+), clockwise rotation (to the right) Levorotary designated as l or (-), anti-clockwise rotation (to the left).

If only one enantiomer is present a sample is considered to be optically pure. When a sample consists of a mixture of enantiomers, the effect of each enantiomer cancels out, molecule for molecule.

For example, a 50:50 mixture of two enantiomers of a racemic mixture will not rotate plane polarised light and is optically inactive. A mixture that contains one enantiomer excess, however, will display a net plane of polarisation in the direction characteristic of the enantiomer that is in excess.

Key Takeaways

- Optical activity is the ability of a chiral molecule to rotate the plane of plane-polarised light, measured using a polarimeter.

- The intensity of optical activity is expressed in terms of a quantity, called specific rotation,

- Specific rotation, [a] is given as [a] = 100a / cl when concentration is expressed as g sample /100ml solution

5.3.2 LAURENT HALF’S HALF SHADE POLARIMETER

Laurent’s half shade Polarimeter

Polarimeter – it is an optical instrument used to measure the angle of rotation of plane-polarized light when it is passed through an optically active substance.

By measuring the angle, the specific rotation of an optically active substance can be determined.

Two types of polarimeters are generally used in the laboratory nowadays Laurent’s Half Shade Polarimeter and Biquartz Polarimeter. We will discuss Laurent’s Half Shade Polarimeter.

Construction

- S is the source of monochromatic light placed at the focus of convex

- Just after the convex lens, there is a Nicol Prism P is placed. This prism acts as a polariser.

- H is a half shade device that divides the field of polarised light emerging out of the Nicol P into two halves generally of unequal brightness.

- T is a glass tube in which an optically active solution is filled.

- The light after passing through T is allowed to fall on the analyzing Nicol A which can be rotated about the axis of the tube. (Don’t get confused here, we already discussed in the previous section that Nicol prism acts as a polariser as well as an analyzer).

- The rotation of the analyzer can be measured with the help of a scale.

Figure 17: Laurent’s half shade polarimeter

Working

To understand the working of this device we have to know the need for a Laurent half shade device. For this, we assume that the half shade device is not present.

In this basic setup (without the half-shade A) you are looking for the maximum and minimum brightness, which then tells you that the analyzer A is precisely aligned with the output rotation.

When the tube is empty placed the analyzer in such a position that the view of the field is completely dark. Note the position of the analyzer with the help of a circular scale.

Now filled the tube with an optically active solution and it is set in its proper position. The optically active solution rotates the plane of polarization of the light emerging out of the polariser P by some angle. So the light is transmitted by analyzer A and the field of view of the telescope becomes bright.

Now the analyzer is rotated by a finite angle so that the field of view of the telescope again becomes dark. This will happen only when the analyzer is rotated by the same angle by which the plane of polarization of light is rotated by the optically active solution.

The position of the analyzer is again noted. The difference between the two readings will give you the angle of rotation of the plane of polarization.

But here the difficulty associated with this procedure that when the analyzer is rotated for the total darkness, then it is attained gradually and hence it is difficult to find the exact position correctly for which complete darkness is obtained.

Figure 18: Laboratory Set-Up of Polarimeter

To overcome the above difficulty half shade device is introduced between polariser P and glass tube T.

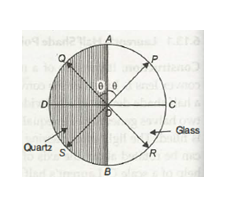

Half Shade Device

- It consists of two semi-circular plates ACB and ADC.

- One-half ACB is made of glass while the other half is made of quartz.

- Both the halves are joined together.

- The quartz is cut parallel to the optic axis.

- The thickness of the quartz is selected in such a way that it introduces a path difference of ‘A/2 between ordinary and extraordinary rays.

- The thickness of the glass is selected in such a way that it absorbs the same amount of light as is absorbed by quartz half.

Figure 19: Half Shade Device

- Let us consider that the vibration of polarisation is along with OP. On passing through the glass half the vibrations remain along with OP. But on passing through quartz half of these vibrations will split into o and e-components.

- The e-components are parallel to the optic axis while the o-component is perpendicular to the optic axis.

- The o-component travels faster in quartz and hence an emergence 0-component will be along with OD instead of along OC.

- Thus components OA and OD will combine to form a resultant vibration along OQ which makes the same angle with the optic axis as OP.

Now if the Principal plane of the analyzing Nicol is parallel to OP then the light will pass through a glass half passable. Hence glass half will be brighter than the quartz half or we can say that the glass half will be bright and the quartz half will be dark. Similarly if the principal plane of analyzing. Nicol is parallel to OQ then quartz half will be bright and glass half will be dark.

When the principal plane of the analyzer is along AOB then both halves will be equally bright. On the other hand, if the principal plane of the analyzer is along with DOC. Then both the halves will be equally dark.

Thus it is clear that if the analysis Nicol is slightly disturbed from DOC then one half becomes brighter than the other. Hence by using a half shade device, one can measure the angle of rotation more accurately.

Mathematically

The specific rotation is given by S=θ/lC where l is the length of the tube and C is concentration.

Key Takeaways

- Polarimeter – it is an optical instrument used to measure the angle of rotation of plane-polarized light when it is passed through an optically active substance.

- Two types of polarimeters are generally used in the laboratory nowadays Laurent’s Half Shade Polarimeter and Biquartz Polarimeter.

The specific rotation is given by S=θ/lC where l is the length of the tube and C is concentration.

1 Example: A parallel beam of monochromatic light of wavelength 500nm is inclined normally on a plane diffraction grating 4000 per centimetre. Calculate the angle of diffraction for first-order principal maximum.

Solution:

Given: number of lines per cm =4000

Grating element e+b = 1/4000 cm = 2.5 x 10-6m

λ=500 nm

Order n =1

(e+b) sinθ =nλ

Sinθ = nλ / (e+b)

Sinθ = 1 x 500 x 10-9 / 2.5 x 10-6

Sinθ =0.2

θ =sin-1 0.2

θ = 11.5o

2. Example: A grating containing 4000 slits per centimetre is illuminated with a monochromatic light and produces the second-order bright line at a 30° angle. What is the wavelength of the light used? (1 Å = 10-10 m)

Solution:

The distance between slits (d) = 1 / (4000 slits / cm) = 0.00025 cm = 2.5 x 10-4 cm = 2.5 x 10-6 meters

Order (n) = 2

Sin 30o = 0.5

1 Å = 10-10 m

Wavelength of the light (λ) =?

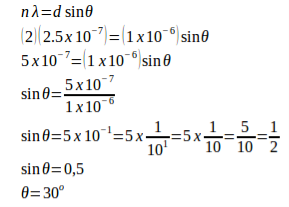

3.Example: A monochromatic light with a wavelength of 2.5x10-7 m strikes a grating containing 10,000 slits/cm. Determine the angular positions of the second-order bright line.

Solution:

Given

The distance between slits (d) = 1 / (10,000 slits / cm) = 0.0001 cm = 1 x 10-4 cm = 1 x 10-6 m

Order (n) = 2

Wavelength (λ) = 2.5 x 10-7 m

Angle (θ)

4.Example: A monochromatic light with a wavelength of 500 nm (1 nm = 10-9 m) strikes a grating and produces the second-order bright line at a 30° angle. Determine the number of slits per centimetre.

Solution:

Wavelength (λ) = 500.10-9 m = 5.10-7 m

θ = 30o

n = 2

Distance between slits:

d sin θ = n λ

d (sin 30o) = (2)(5.10-7)

d (0.5) = 10.10-7

d = (10.10-7) / 0.5

d = 20.10-7

d = 2.10-6 m

Number of slits per centimetre:

x = 1 / d

x = 1 / 2.10-6 m

x = 0.5.106 / 1 m

x = 0.5.106 / 102 cm

x = 0.5.104 cm

x = 5.103 /cm

x = 5000 /cm

5.Example: A monochromatic light with a wavelength of 500 nm (1 nano = 10-9) strikes a grating and produces the fourth-order bright line at a 30° angle. Determine the number of slits per centimetre.

Solution:

Wavelength (λ) = 500.10-9 m = 5.10-7 m

θ = 30o

n = 4

Distance between slits:

d sin θ = n λ

d (sin 30o) = (4)(5.10-7)

d (0.5) = 20.10-7

d = (20.10-7) / 0.5

d = 40.10-7

d = 4.10-6 m

Number of slits per centimetre:

x = 1 / 4.10-6 m

x = 0.25.106 / m

x = 0.25.106 / 102 cm

x = 0.25.104 / cm

x = 25.102 per cm

x = 2500 per cm

6 Example: A grating has 1100 lines ruled on it. What is the difference between the two wavelengths that just appear resolved in the first-order spectrum in the region of wavelength λ = 660 nm?

Solution:

N = 1100 nm

λ = 660 x 10-9 m

n = 1

R = λ /dλ =Nn

dλ = λ /Nn

dλ = 660 x 10-9 / 1100 x 10-9 x 1

dλ = 0.6 x 10-9 m

Reference

- Fundamentals of optics-Jenkins and White. McGraw Hill Publication

- A Text Book of Optics Subrahmanyam, BrijIal, S. Chand Publication

- Optics by Ajay Ghatak

- Engineering physics - Avadhanalu and Kshirsagar, S.Chand Publication