Unit - 2

Linear algebra

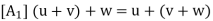

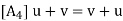

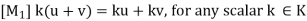

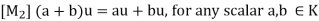

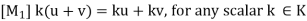

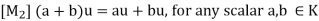

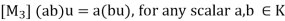

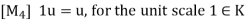

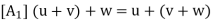

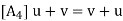

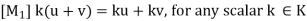

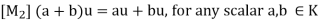

We define a vector space V where K is the field of scalars as follows-

Let V be a nonempty set with two operations-

(i) Vector Addition: This assigns to any u; v  V a sum u + v in V.

V a sum u + v in V.

(ii) Scalar Multiplication: This assigns to any u  V, k

V, k  K a product ku

K a product ku  V.

V.

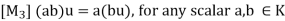

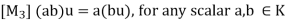

Then V is called a vector space (over the field K) if the following axioms hold for any vectors u; v; w  V:

V:

There is a vector in V, denoted by 0 and called the zero vector, such that, for any u

There is a vector in V, denoted by 0 and called the zero vector, such that, for any u  V;

V;

For each u

For each u  V; there is a vector in V, denoted by -u, and called the negative of u, such that

V; there is a vector in V, denoted by -u, and called the negative of u, such that

u + (-u) (-u) + u = 0

The above axioms naturally split into two sets (as indicated by the labeling of the axioms). The first four are concerned only with the additive structure of V and can be summarized by saying V is a commutative group under addition.

This means

(a) Any sum v1 + v2 +……+vm of vectors requires no parentheses and does not depend on the order of the summands.

(b) The zero vector 0 is unique, and the negative -u of a vector u is unique.

(c) (Cancellation Law) If u + w = v + w, then u = v.

Also, subtraction in V is defined by u - v = u + (-v), where -v is the unique negative of v.

Theorem: Let V be a vector space over a field K.

(i) For any scalar k  K and 0

K and 0  V; k0 = 0.

V; k0 = 0.

(ii) For 0  K and any vector u

K and any vector u  V; 0u = 0.

V; 0u = 0.

(iii) If ku = 0, where k  K and u

K and u  V, then k = 0 or u = 0.

V, then k = 0 or u = 0.

(iv) For any k  K and any u

K and any u  V; (-k)u = k(-u) = -ku.

V; (-k)u = k(-u) = -ku.

Examples of Vector Spaces:

Space  Let K be an arbitrary field. The notation

Let K be an arbitrary field. The notation  is frequently used to denote the set of all n-tuples of elements in K. Here

is frequently used to denote the set of all n-tuples of elements in K. Here  is a vector space over K using the following operations:

is a vector space over K using the following operations:

(i) Vector Addition:

(a1, a2, . . . an) + (b1 , b2, . . ., bn) = (a1 + b1, a2 + b2 , . . . an + bn)

(ii) Scalar Multiplication

k(a1, a2, . . ., an) = (ka1, ka2, . . . Kan)

The zero vector in  is the n-tuple of zeros

is the n-tuple of zeros

0 = (0,0,…,0)

And the negative of a vector is defined by

-(a1, a2, . . . , an) = ( - a1, - a2, . . . , - an)

Polynomial Space P(t):

Let P(t) denote the set of all polynomials of the form

p(t) = a0 + a1t + a2t2 + . . . + asts (s = 1, 2, . . .)

Where the coefficients ai belong to a field K. Then PðtÞ is a vector space over K using the following operations:

(i) Vector Addition: Here p(t)+ q(t) in P(t) is the usual operation of addition of polynomials.

(ii) Scalar Multiplication: Here kp(t) in P(t) is the usual operation of the product of a scalar k and a polynomial p(t). The zero polynomial 0 is the zero vector in P(t)

Function Space F(X):

Let X be a nonempty set and let K be an arbitrary field. Let F(X) denote the set of all functions of X into K. [Note that F(X) is nonempty, because X is nonempty.] Then F(X) is a vector space over K with respect to the following operations:

(i) Vector Addition: The sum of two functions f and g in F(X) is the function f + g in F(X) defined by

(f +g)(x) = f(x) + g(x) ∀ x ∈ X

(ii) Scalar Multiplication: The product of a scalar k belongs to K and a function f in F(X) is the function kf in F(X) defined by

(kf)(x) = kf(x) ∀ x ∈ X

The zero vector in F(X) is the zero function 0, which maps every x belngs to X into the zero element 0 belongs to K;

0(x) = 0 ∀ x ∈ X

Also, for any function f in F(X), negative of f is the function -f in F(X) defined by

(-f)(x) = - f(x) ∀ x ∈ X

Fields and Subfields

Suppose a field E is an extension of a field K; that is, suppose E is a field that contains K as a subfield. Then E may be viewed as a vector space over K using the following operations:

(i) Vector Addition: Here u + v in E is the usual addition in E.

(ii) Scalar Multiplication: Here ku in E, where k  K and u

K and u  E, is the usual product of k and u as elements of E.

E, is the usual product of k and u as elements of E.

Vector-

An ordered n – tuple of numbers is called an n – vector. Thus the ‘n’ numbers x1, x2, …………xn taken in order denote the vector x. i.e. x = (x1, x2, ……., xn).

Where the numbers x1, x2, ………..,xn are called component or co – ordinates of a vector x. A vector may be written as row vector or a column vector.

If A be an mxn matrix then each row will be an n – vector & each column will be an m – vector.

Linear dependence-

A set of n – vectors. x1, x2, …….., xr is said to be linearly dependent if there exist scalars. k1, k2, …….,kr not all zero such that

k1 + x2k2 + …………….. + xrkr = 0 … (1)

Linear independence-

A set of r vectors x1, x2, ………….,xr is said to be linearly independent if there exist scalars k1, k2, …………, kr all zero such that

x1 k1 + x2 k2 + …….. + xrkr = 0

Important notes-

- Equation (1) is known as a vector equation.

- If the vector equation has non – zero solution i.e. k1, k2, ….,kr not all zero. Then the vector x1, x2, ……….xr are said to be linearly dependent.

- If the vector equation has only trivial solution i.e.

k1 = k2 = …….=kr = 0. Then the vector x1, x2, ……,xr are said to linearly independent.

Linear combination-

A vector x can be written in the form.

x = x1 k1 + x2 k2 + ……….+xrkr

Where k1, k2, ………….., kr are scalars, then X is called linear combination of x1, x2, ……, xr.

Results:

- A set of two or more vectors are said to be linearly dependent if at least one vector can be written as a linear combination of the other vectors.

- A set of two or more vector are said to be linearly independent then no vector can be expressed as linear combination of the other vectors.

Linear spans:

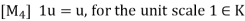

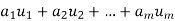

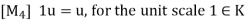

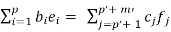

Suppose  are any vectors in a vector space V. Recall that any vector of the form

are any vectors in a vector space V. Recall that any vector of the form  , where the ai are scalars, is called a linear combination of

, where the ai are scalars, is called a linear combination of  .

.

The collection of all such linear combinations, denoted by Span( or span(

or span( Clearly the zero vector 0 belongs to span

Clearly the zero vector 0 belongs to span , because

, because

0 = 0u1 + 0u2 + . . . + 0um

Furthermore, suppose v and v’ belong to span ,, say,

,, say,

v = a1u1 + a2u2 + . . . + amum and v’ =b1u1 + b2u2 + . . . + bmum

Then

v + v’ = (a1 + b1)u1 + (a2 + b2)u2 + . . . + (am + bm)um

And, for any scalar k belongs to K,

Kv = ka1u1 + ka2u2 + . . . + kamum

Thus, v + v’ and kv also belong to span . Accordingly, span

. Accordingly, span is a subspace of V.

is a subspace of V.

Spanning sets:

Let V be a vector space over K. Vectors  in V are said to span V or to form a spanning set of V if every v in V is a linear combination of the vectors

in V are said to span V or to form a spanning set of V if every v in V is a linear combination of the vectors  —that is, if there exist scalars

—that is, if there exist scalars  in K such that

in K such that

v = a1u1 + a2u2 + . . . + amum

Note-

- Suppose

span V. Then, for any vector w, the set w;

span V. Then, for any vector w, the set w;  also spans V.

also spans V. - Suppose

span V and suppose uk is a linear combination of some of the other u’s. Then the u’s without

span V and suppose uk is a linear combination of some of the other u’s. Then the u’s without  also span V.

also span V. - Suppose

span V and suppose one of the u’s is the zero vector. Then the u’s without the zero vector also span V.

span V and suppose one of the u’s is the zero vector. Then the u’s without the zero vector also span V.

Example: Let consider a vector space V =

(a) We claim that the following vectors form a spanning set of

c1 = (1, 0, 0), c2 = (0, 1, 0) c3 = (0, 0, 1)

Specifically, if v = (a b c) is any vector in  , then

, then

v = ae1 + be2 + ce3

For example,

v = (5, -6, 2) = -5e1 – 6e2 + 2e3

(b) We claim that the following vectors also form a spanning set of

w1 = (1, 1, 1), w2 = (1, 1, 0), w3 = (1, 0, 0)

Specifically, if v = (a b c) is any vector in  , then

, then

v = (a, b, c) = cw1 + (b – c)w2 + (a-b)w3

For example,

v = (5, -6, 2) = 2w1 – 8w2 + 11w3

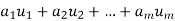

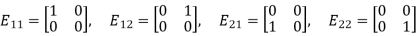

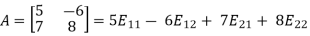

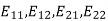

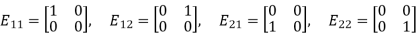

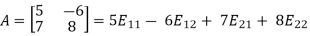

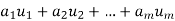

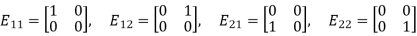

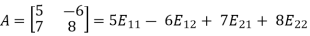

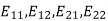

Example: Consider the vector space M =  consisting of all 2 by 2 matrices, and consider the following four matrices in M:

consisting of all 2 by 2 matrices, and consider the following four matrices in M:

Then clearly any matrix A in M can be written as a linear combination of the four matrices. For example,

Accordingly, the four matrices  span M.

span M.

First we will go through some important definitions before studying Eigen values and Eigen vectors.

1. Vector-

An ordered n – touple of numbers is called an n – vector. Thus the ‘n’ numbers x1, x2, …………xn taken in order denote the vector x. i.e. x = (x1, x2, ……., xn).

Where the numbers x1, x2, ………..,xn are called component or co – ordinates of a vector x. A vector may be written as row vector or a column vector.

If A be an mxn matrix then each row will be an n – vector & each column will be an m – vector.

2. Linear dependence-

A set of n – vectors. x1, x2, …….., xr is said to be linearly dependent if there exist scalars. k1, k2, …….,kr not all zero such that

k1 + x2k2 + …………….. + xrkr = 0 … (1)

3. Linear independence-

A set of r vectors x1, x2, ………….,xr is said to be linearly independent if there exist scalars k1, k2, …………, kr all zero such that

x1 k1 + x2 k2 + …….. + xrkr = 0

Important notes-

- Equation (1) is known as a vector equation.

- If the vector equation has non – zero solution i.e. k1, k2, ….,kr not all zero. Then the vector x1, x2, ……….xr are said to be linearly dependent.

- If the vector equation has only trivial solution i.e.

k1 = k2 = …….=kr = 0. Then the vector x1, x2, ……,xr are said to linearly independent.

4. Linear combination-

A vector x can be written in the form.

x = x1 k1 + x2 k2 + ……….+xrkr

Where k1, k2, ………….., kr are scalars, then X is called linear combination of x1, x2, ……, xr.

Results:

- A set of two or more vectors are said to be linearly dependent if at least one vector can be written as a linear combination of the other vectors.

- A set of two or more vector are said to be linearly independent then no vector can be expressed as linear combination of the other vectors.

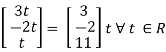

Example 1

Are the vectors x1 = [1, 3, 4, 2], x2 = [1, 3, 4, 2], x3 = [3, -5, 2, 6], linearly dependent. If so, express x1 as a linear combination of the others.

Solution:

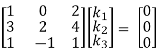

Consider a vector equation,

x1k1 + x2k2 + x3k3 = 0

i.e., [1, -3, 4, 2]k1 + [3, -5, 2,6]k2 + [2, -1, 3, 4]k3 = [0, 0, 0, 0]

∴ k1 +3k2 + 2k3 = 0

+3k1 + 5k2 + k3 = 0

4k1 + 2k2 + 3k3 = 0

2k1 + 6k2 + 4k3 =0

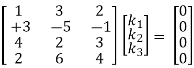

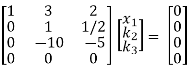

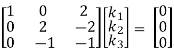

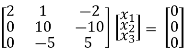

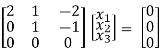

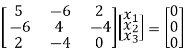

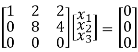

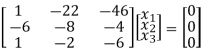

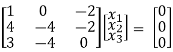

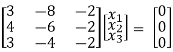

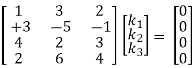

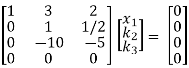

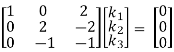

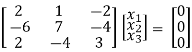

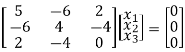

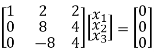

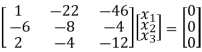

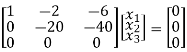

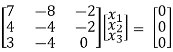

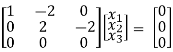

Which can be written in matrix form as,

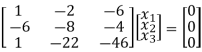

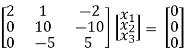

R2 + 3R1, R3 – 4R1, R4 – 2R1

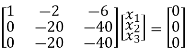

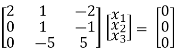

1/14 R2

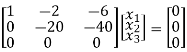

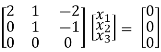

R3 + 10R2

Here ρ(A) = 2 & no. Of unknown 3. Hence the system has infinite solutions. Now rewrite the questions as,

k1 + 3k2 + 2k3 =0

k2 + ½ k3 =0

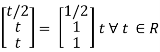

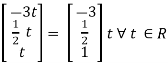

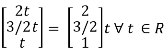

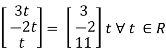

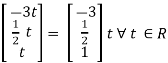

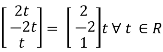

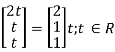

Put k3 =t

k2 = -1/2 t and

k1 = -3k2 – 2k3

= - 3 (- ½ t) -2t

= 3/2 t – 2t

= - t/2

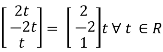

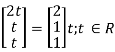

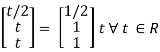

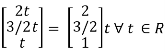

Thus k1 = - t/2, k2 = -1/2 t – k3 = t ∀ t ∈ R

i.e., - t/2 × 1 + ( - t/2) x2 + t × 3 = 0

i.e.,- x1/2 – (-x2/2) + x3 = 0

- x1 – x2 + 2 x3 = 0

x1 = - x2 + 2 x3

Since F11k2, k3 not all zero. Hence x1, x2, x3 are linearly dependent.

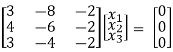

Example 2

Examine whether the following vectors are linearly independent or not.

x1 = [3, 1, 1], x2 = [2, 0, -1] and x3 = [4, 2, 1]

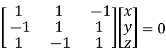

Solution:

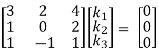

Consider the vector equation,

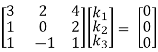

x1k1 + x2k2 + x3k3 = 0

i.e., [3, 1, 1] k1 + [2, 0, -1]k2 + [4, 2, 1]k3 = 0 ...(1)

3k1 + 2k2 + 4k3 = 0

k1 + 2k3 = 0

k1 – k2 + k3 = 0

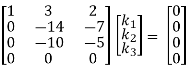

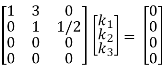

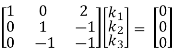

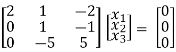

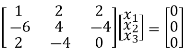

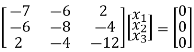

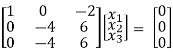

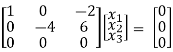

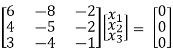

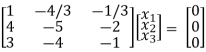

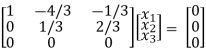

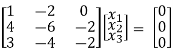

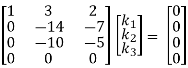

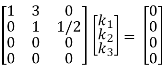

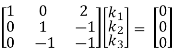

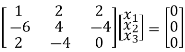

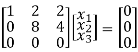

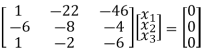

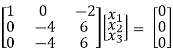

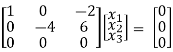

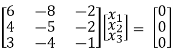

Which can be written in matrix form as,

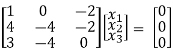

R12

R2 – 3R1, R3 – R1

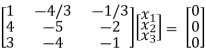

+ ½ R2

R3 + R2

Here Rank of coefficient matrix is equal to the no. Of unknowns. i.e. r = n = 3.

Hence the system has unique trivial solution.

i.e. k1 = k2 = k3 = 0

i.e. vector equation (1) has only trivial solution. Hence the given vectors x1, x2, x3 are linearly independent.

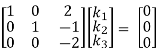

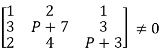

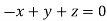

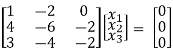

Example 3

At what value of P the following vectors are linearly independent.

[1, 3, 2], [2, P+7, 4], [1, 3, P+3]

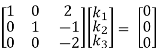

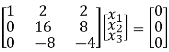

Solution:

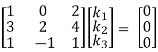

Consider the vector equation.

[1, 3, 2]k1 + [2, P+7, 4]k2 + [1, 3, P+3]k3 = 0

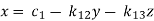

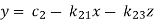

i.e.

k1 + 2k2 + k3 = 0

3k1 + (p + 7)k2 + 3k3 = 0

2k1 + 4k2 + (P +3)k3 = 0

This is a homogeneous system of three equations in 3 unknowns and has a unique trivial solution.

If and only if Determinant of coefficient matrix is non zero.

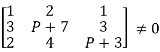

consider

consider  .

.

i.e.,

1[(P + λ)(P+3) – 12] – 2[3(P+3) – 6] + 1[12 – (2P + 14)]  0

0

P2 + 10P + 21 – 12 -6P – 6 – 2P – 2

P2 + 2P + 1

(P + 1)2

(P + 1)

P

Thus for  the system has only trivial solution and Hence the vectors are linearly independent.

the system has only trivial solution and Hence the vectors are linearly independent.

Note:-

If the rank of the coefficient matrix is r, it contains r linearly independent variables & the remaining vectors (if any) can be expressed as linear combination of these vectors.

Characteristic equation:

Let A he a square matrix, λ be any scalar then |A – λI| = 0 is called characteristic equation of a matrix A.

Note:

Let a be a square matrix and ‘λ’ be any scalar then,

1) [A – λI] is called characteristic matrix

2) | A – λI| is called characteristic polynomial.

The roots of a characteristic equations are known as characteristic root or latent roots, Eigen values or proper values of a matrix A.

Eigen vector:

Suppose λ1 be an Eigen value of a matrix A. Then ∃ a non – zero vector x1 such that.

[A – λI] x1 = 0 ...(1)

Such a vector ‘x1’ is called as Eigen vector corresponding to the Eigen value λ1

Properties of Eigen values:

- Then sum of the Eigen values of a matrix A is equal to sum of the diagonal elements of a matrix A.

- The product of all Eigen values of a matrix A is equal to the value of the determinant.

- If λ1, λ2, λ3, ..., λn are n Eigen values of square matrix A then 1/λ1, 1/λ2, 1/λ3, ..., 1/λn are m Eigen values of a matrix A-1.

- The Eigen values of a symmetric matrix are all real.

- If all Eigen values are non –zero then A-1 exist and conversely.

- The Eigen values of A and A’ are same.

Properties of Eigen vector:

- Eigen vector corresponding to distinct Eigen values are linearly independent.

- If two are more Eigen values are identical then the corresponding Eigen vectors may or may not be linearly independent.

- The Eigen vectors corresponding to distinct Eigen values of a real symmetric matrix are orthogonal.

Example1: Find the sum and the product of the Eigen values of  ?

?

Sol. The sum of Eigen values = the sum of the diagonal elements

=1+(-1)=0

=1+(-1)=0

The product of the Eigen values is the determinant of the matrix

On solving above equations we get

Example2: Find out the Eigen values and Eigen vectors of  ?

?

Sol. The Characteristics equation is given by

Or

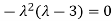

Hence the Eigen values are 0,0 and 3.

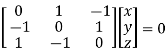

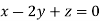

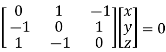

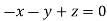

The Eigen vector corresponding to Eigen value  is

is

Where X is the column matrix of order 3 i.e.

This implies that

Here number of unknowns are 3 and number of equation is 1.

Hence we have (3-1) = 2 linearly independent solutions.

Let

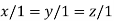

Thus the Eigen vectors corresponding to the Eigen value  are (-1,1,0) and (-2,1,1).

are (-1,1,0) and (-2,1,1).

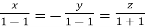

The Eigen vector corresponding to Eigen value  is

is

Where X is the column matrix of order 3 i.e.

This implies that

Taking last two equations we get

Or

Thus the Eigen vectors corresponding to the Eigen value  are (3,3,3).

are (3,3,3).

Hence the three Eigen vectors obtained are (-1,1,0), (-2,1,1) and (3,3,3).

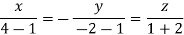

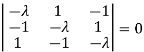

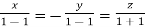

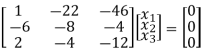

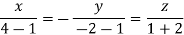

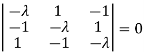

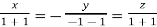

Example3: Find out the Eigen values and Eigen vectors of

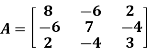

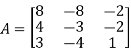

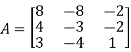

Sol. Let A =

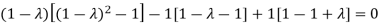

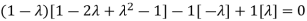

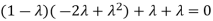

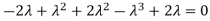

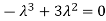

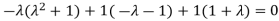

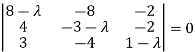

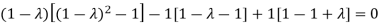

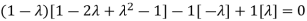

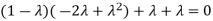

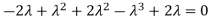

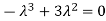

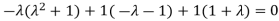

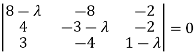

The characteristics equation of A is  .

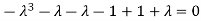

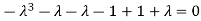

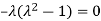

.

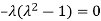

Or

Or

Or

Or

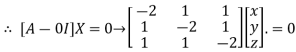

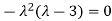

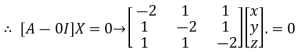

The Eigen vector corresponding to Eigen value  is

is

Where X is the column matrix of order 3 i.e.

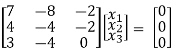

Or

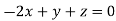

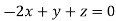

On solving we get

Thus the Eigen vectors corresponding to the Eigen value  is (1,1,1).

is (1,1,1).

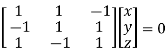

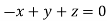

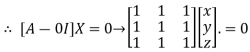

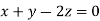

The Eigen vector corresponding to Eigen value  is

is

Where X is the column matrix of order 3 i.e.

Or

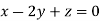

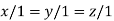

On solving  or

or  .

.

Thus the Eigen vectors corresponding to the Eigen value  is (0,0,2).

is (0,0,2).

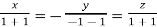

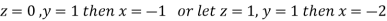

The Eigen vector corresponding to Eigen value  is

is

Where X is the column matrix of order 3 i.e.

Or

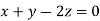

On solving we get  or

or  .

.

Thus the Eigen vectors corresponding to the Eigen value  is (2,2,2).

is (2,2,2).

Hence three Eigen vectors are (1,1,1), (0,0,2) and (2,2,2).

Example-4:

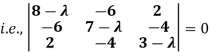

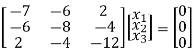

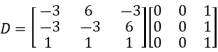

Determine the Eigen values of Eigen vector of the matrix.

Solution:

Consider the characteristic equation as, |A – λI| = 0

i.e., (8 – λ) (21 - 10 λ + λ2 – 16) + 6(-18 + 6 λ + 8) + 2(24 – 14 + 2 λ) =0

(8- λ)( λ2 -10 λ + 5) + 6(6 λ – 10) + 2(2 λ + 10) = 0

8 λ2 - 80 λ + 40 – λ3 + 10 λ2 - 5 λ + 36 λ – 60

- λ3 + 18 λ - 45 λ = 0

i.e., λ3 – 18 λ + 45 λ = 0

Which is the required characteristic equation.

λ(λ2 - 18 λ + 45) = 0

λ(λ – 15)( λ – 3) = 0

λ = 0, 15, 3 are the required Eigen values.

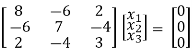

Now consider the equation

[A – λI] x = 0 ...................(1)

Case I:

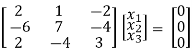

If λ = 0 Equation (1) becomes

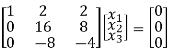

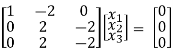

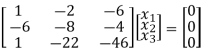

R1 + R2

R2 + 3R1, R3 – R1

-1/1 R2

R3 + 5R2

Thus ρ[A – λI] = 2 & n = 3

3 – 2 = 1 independent variable.

Now rewrite equation as,

2x1 + x2 – 2x3 = 0

x2 – x3 = 0

Put x3 = t

x2 = t &

2x1 = - x2 + 2x3

2x1 = -t + 2t

x1 = t/2

Thus x1 =

Is the eigen vector corresponding to λ = t.

Case II:

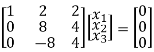

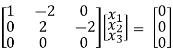

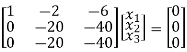

If λ = 3 equation (1) becomes,

R1 – 2R3

R2 + 6R1 , R3 – 2R1

½ R2

R3+R2

Here ρ[A – λI] = 2, n = 3

3-2 = 1 Independent variables

Now rewrite the equations as,

x1 + 2x2 + 2x3 = 0

8x2 + 4x3 = 0

Put x3 = t

x2 = ½ t &

x1 = -2x2 – 2x3

= - 2 ( ½ ) t – 2 (t)

= - 3t

x2 =

Is the eigen vector corresponding to λ = 3.

Case III:

If λ = 15 equation (1) becomes,

R1 + 4R3

½ R3

R13

R2 + 6R1 , R3 – R1

R3 – R2

Here rank of [ A – λ I] = 2 & n = 3

3 – 2 = 1 independent variable

Now rewrite the equations as,

x1 – 2x2 – 6x3 = 0

-20x2 – 40x3 =0

Put x3 = t

x2 = - 2t & x1 = 2t

Thus x3 =

Is the eigen vector for λ = 13.

Example-5:

Find the Eigen values of Eigen vector for the matrix.

Solution:

Consider the characteristic equation as |A – λ I| = 0

i.e.,

(8 –  (-3 + 3λ – λ + λ2 – 8) + 8(4 - 4 λ + 6) – 2(-16 + 9 + 3 λ) = 0

(-3 + 3λ – λ + λ2 – 8) + 8(4 - 4 λ + 6) – 2(-16 + 9 + 3 λ) = 0

(8 – λ)( λ2 + 2 λ – 1) + 8(0 - 4 λ) – 2(3 λ – 7) = 0

8 λ2 + 16 λ – 88 – λ3 - 2 λ2 + 11 λ + 80 - 32 λ - 6 λ + 14 = 0

i.e., - λ3 + 6 λ2 - 11 λ + 6 = 0

λ3 - 6 λ2 + 11 λ + 6 = 0

(λ – 1)( λ – 2)( λ – 3) = 0

λ = 1, 2, 3 are the required eigen values

Now consider the equation

[A – λI] x = 0 ..............(1)

Case I:

λ = 1 Equation (1) becomes,

R1 – 2R3

R2 – 4R1, R3 – 3R1

R3 – R2

Thus ρ[A – λI] = 2 and n = 3

3 – 2 = 1 independent variables

Now rewrite the equations as,

x1 – 2x3 = 0

-4x2 + 6x3 = 0

Put x3= t

x2 = 3/2 t , x1 = 2b

x1 =

I.e.

The Eigen vector for

Case II:

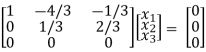

If λ = 2 equation (1) becomes,

1/6 R1

R2 – 4R1, R3 – 3 R1

Thus ρ(A – λI) = 2 & n = 3

3 – 2 = 1

Independent variables.

Now rewrite the equations as,

x1 – 4/3 x2 – 1/3 x3 = 0

1/3 x2 + 2/3 x3 = 0

Put x3 = t

1/3 x2 = - 2/3 t

x2 = -2t

x1 = - 4/3 x2 + 1/3 x3

= (-4)/3 (-2t) + 1/3 t

= 3t

X2 =

Is the Eigen vector for λ = 2

Now

Case III:

If λ = 3 equation (1) gives,

R1 – R2

R2 – 4R1, R3 – 3R1

R3 – R2

Thus ρ[A – λI] = 2 & n = 3

3 – 2 = 1

Independent variables

Now x1 – 2x2 = 0

2x2 – 2x3 = 0

Put x3 = t, x2 = t, x1 = 25

Thus

x3 =

Is the Eigen vector for λ = 3

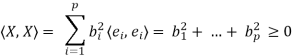

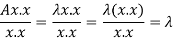

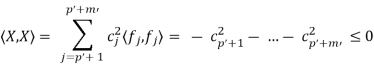

Rayleigh's power method-

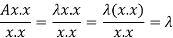

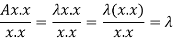

Suppose x be an eigen vector of A. Then the eigen value  corresponding to this eigen vector is given as-

corresponding to this eigen vector is given as-

This quotient is called Rayleigh’s quotient.

Proof:

Here x is an eigen vector of A,

As we know that  ,

,

We can write-

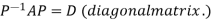

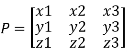

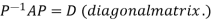

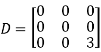

Diagonalization of a square matrix of order two

Two square matrix  and A of same order n are said to be similar if and only if

and A of same order n are said to be similar if and only if

for some non singular matrix P.

for some non singular matrix P.

Such transformation of the matrix A into  with the help of non singular matrix P is known as similarity transformation.

with the help of non singular matrix P is known as similarity transformation.

Similar matrices have the same Eigen values.

If X is an Eigen vector of matrix A then  is Eigen vector of the matrix

is Eigen vector of the matrix

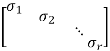

Reduction to Diagonal Form:

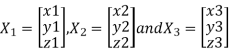

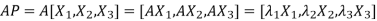

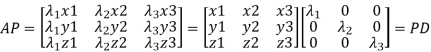

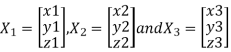

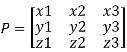

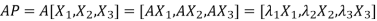

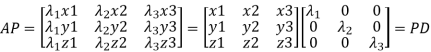

Let A be a square matrix of order n has n linearly independent Eigen vectors Which form the matrix P such that

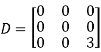

Where P is called the modal matrix and D is known as spectral matrix.

Procedure: let A be a square matrix of order 3.

Let three Eigen vectors of A are  Corresponding to Eigen values

Corresponding to Eigen values

Let

{by characteristics equation of A}

{by characteristics equation of A}

Or

Or

Note: The method of diagonalization is helpful in calculating power of a matrix.

.Then for an integer n we have

.Then for an integer n we have

We are using the example of 1.6*

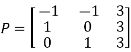

Example1: Diagonalise the matrix

Let A=

The three Eigen vectors obtained are (-1,1,0), (-1,0,1) and (3,3,3) corresponding to Eigen values  .

.

Then  and

and

Also we know that

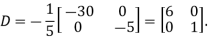

Example2: Diagonalise the matrix

Let A =

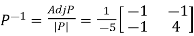

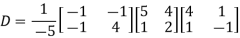

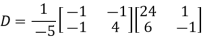

The Eigen vectors are (4,1),(1,-1) corresponding to Eigen values  .

.

Then  and also

and also

Also we know that

Singular value decomposition:

The singular value decomposition of a matrix is usually referred to as the SVD. This is the final and best factorization of a matrix

Where U is orthogonal, Σ is diagonal, and V is orthogonal.

In the decomoposition

A can be any matrix. We know that if A is symmetric positive definite its eigenvectors are orthogonal and we can write A = QΛ . This is a special case of a SVD, with U = V = Q. For more general A, the SVD requires two different matrices U and V. We’ve also learned how to write A = SΛ

. This is a special case of a SVD, with U = V = Q. For more general A, the SVD requires two different matrices U and V. We’ve also learned how to write A = SΛ , where S is the matrix of n distinct eigenvectors of A. However, S may not be orthogonal; the matrices U and V in the SVD will be

, where S is the matrix of n distinct eigenvectors of A. However, S may not be orthogonal; the matrices U and V in the SVD will be

Working of SVD:

We can think of A as a linear transformation taking a vector v1 in its row space to a vector u1 = Av1 in its column space. The SVD arises from finding an orthogonal basis for the row space that gets transformed into an orthogonal basis for the column space: Avi = σiui. It’s not hard to find an orthogonal basis for the row space – the Gram Schmidt process gives us one right away. But in general, there’s no reason to expect A to transform that basis to another orthogonal basis. You may be wondering about the vectors in the null spaces of A and  . These are no problem – zeros on the diagonal of Σ will take care of them.

. These are no problem – zeros on the diagonal of Σ will take care of them.

Matrix form:

The heart of the problem is to find an orthonormal basis v1, v2, ...vr for the row space of A for which

A[ v1 v2 ... vr] = [ σ1u1 σ2u2 . . . σrur] = [ u1 u2 . . . ur]

With u1, u2, ...ur an orthonormal basis for the column space of A. Once we add in the null spaces, this equation will become AV = UΣ. (We can complete the orthonormal bases v1, ...vr and u1, ...ur to orthonormal bases for the entire space any way we want. Since  , ...

, ... will be in the null space of A, the diagonal entries

will be in the null space of A, the diagonal entries  , ...

, ... will be 0.) The columns of U and V are bases for the row and column spaces, respectively. Usually U is not equal to V, but if A is positive definite we can use the same basis for its row and column space.

will be 0.) The columns of U and V are bases for the row and column spaces, respectively. Usually U is not equal to V, but if A is positive definite we can use the same basis for its row and column space.

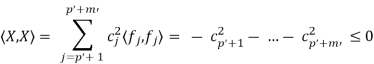

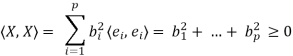

Sylvester theorem: Let A be the matrix of a symmetric bilinear form, of a finite dimenasional vector space, with respect to an orthogonal basis. Then the number of 1’s and -1’s and 0’s is independent of the choice of orthogonal basis.

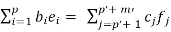

Proof:

Let {e1, . . . , en} be an orthogonal basis of V such that the diagonal matrix A representing the form has only 1, -1 and 0 on the diagonal. By permuting the basis we can furthermore assume that the first p basis vectors are such that hei , eii = 1, the m next vectors give -1, and the final s = n − (p + m) vectors produce the zeros. It follows that s = n − (p + m) is the dimension of the null-space AX = 0. Therefore the number s = n − (p + m) of zeros on the diagonal is unique. Assume that we have found another orthogonal basis of V such that the diagonal matrix representing the form has first p 0 diagonal elements equal to 1, next m0 diagonal elements equal to -1, and the remaining s = n−(p 0 +m0 ) diagonal elements are zero. Let {f1, . . . , fn} be such a basis. We then claim that the p + m0 vectors e1, . . . , ep, fp 0+1, . . . , fp 0+m0 are linearly independent. Assume the converse, that there is a linear relation between these vectors.

Such a relation we can split as

..........................(1)

..........................(1)

The vector occurring on the left hand side we call X. We have that

The vector X also occurs on the right hand side of (1), and gives that

These two expressions for the number hX, Xi implies that b1 = · · · = bp = 0 and that cp 0+1 = · · · = cp 0+m0 = 0. In other words we have proven tha

The p+ m0 vectors e1, . . . , ep, fp 0+1, . . . , fp 0+m0 are linearly independent. Their total number can not exceed s which gives p+m0 ≤ s. Thus p ≤ p 0 . However, the argument presented is symmetric, and we can interchange the role of p 0 and p, from where it follows that p = p 0 . Thus the number of 1’s is unique. It then follows that also the number of -1’s is unique.

The pair (p, m) where p is the number of 1’s and m is the number of -1’s is called the signature of the form. To a given signature (p, m) we have the diagonal (n × n)-matrix Ip,m whose first p diagonal elements are 1, next m diagonal elements are -1, and the remaining diagonal (n − p − m) elements are 0.

Examples:

- Let V be the vector space of real (2 × 2)-matrices. (a) Show that the form hA, Bi = det(A + B) − det(A) − det(B) is symmetric and bilinear. (b) Compute the matrix A representing the above form with respect to the standard basis {E11, E12, E21, E22}, and determine the signature of the form. (c) Let W be the sub-vector space of V consisting of trace zero matrices. Compute the signature of the form discribed above, restricted to W.

- 2. Determine the signature of the form hA, Bi = Trace(AtrB) on the space of real (n × n)-matrices.

Rayleigh's power method-

Suppose x be an eigen vector of A. Then the eigen value  corresponding to this eigen vector is given as-

corresponding to this eigen vector is given as-

This quotient is called Rayleigh’s quotient.

Proof:

Here x is an eigen vector of A,

As we know that  ,

,

We can write-

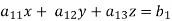

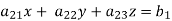

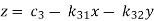

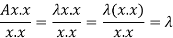

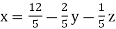

Gauss-Seidel iteration method-

Step by step method to solve the system of linear equation by using Gauss Seidal Iteration method-

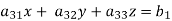

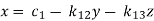

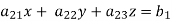

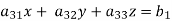

Suppose,

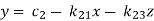

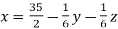

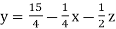

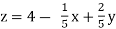

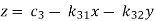

This system can be written as after dividing it by suitable constants,

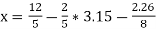

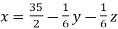

Step-1 Here put y = 0 and z = 0 and x =  in first equation

in first equation

Then in second equation we put this value of x that we get the value of y.

In the third eq. We get z by using the values of x and y

Step-2: we repeat the same procedure

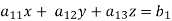

Example: solve the following system of linear equations by using Guass seidel method-

6x + y + z = 105

4x + 8y + 3z = 155

5x + 4y - 10z = 65

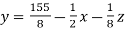

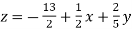

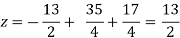

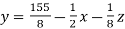

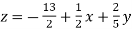

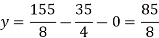

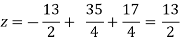

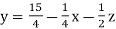

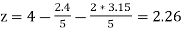

Sol. The above equations can be written as,

………………(1)

………………(1)

………………………(2)

………………………(2)

………………………..(3)

………………………..(3)

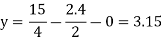

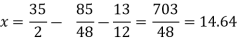

Now put z = y = 0 in first eq.

We get

x = 35/2

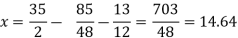

Put x = 35/2 and z = 0 in eq. (2)

We have,

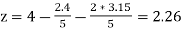

Put the values of x and y in eq. 3

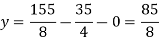

Again start from eq.(1)

By putting the values of y and z

y = 85/8 and z = 13/2

We get

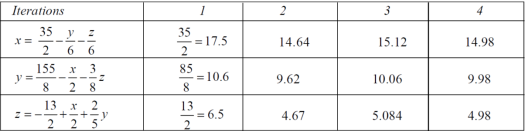

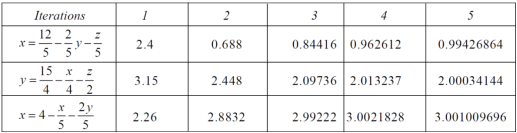

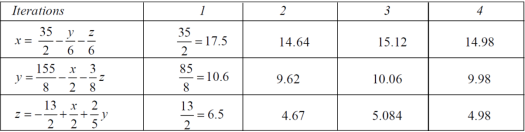

The process can be showed in the table format as below

At the fourth iteration, we get the values of x = 14.98, y = 9.98 , z = 4.98

Which are approximately equal to the actual values,

As x = 15, y = 10 and y = 5 ( which are the actual values)

Example: Solve the following system of linear equations by using Gauss-seidel method-

5x + 2y + z = 12

x + 4y + 2z = 15

x + 2y + 5z = 20

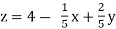

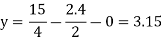

Sol. These equations can be written as,

………………(1)

………………(1)

………………………(2)

………………………(2)

………………………..(3)

………………………..(3)

Put y and z equals to 0 in eq. 1

We get,

x = 2.4

Put x = 2.4, and z = 0 in eq. 2 , we get

Put x = 2.4 and y = 3.15 in eq.(3) , we get

Again start from eq.(1), put the values of y and z , we get

= 0.688

= 0.688

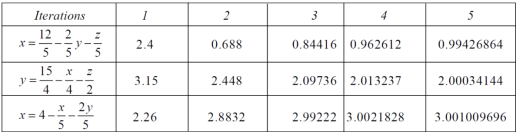

We repeat the process again and again,

The following table can be obtained –

Here we see that the values are approx. Equal to exact values.

Exact values are, x = 1, y = 2, z = 3.

References:

- E. Kreyszig, “Advanced Engineering Mathematics”, John Wiley & Sons, 2006.

- P. G. Hoel, S. C. Port And C. J. Stone, “Introduction To Probability Theory”, Universal Book Stall, 2003.

- S. Ross, “A First Course in Probability”, Pearson Education India, 2002.

- W. Feller, “An Introduction To Probability Theory and Its Applications”, Vol. 1, Wiley, 1968.

- N.P. Bali and M. Goyal, “A Text Book of Engineering Mathematics”, Laxmi Publications, 2010.

- B.S. Grewal, “Higher Engineering Mathematics”, Khanna Publishers, 2000.

Unit - 2

Linear algebra

We define a vector space V where K is the field of scalars as follows-

Let V be a nonempty set with two operations-

(i) Vector Addition: This assigns to any u; v  V a sum u + v in V.

V a sum u + v in V.

(ii) Scalar Multiplication: This assigns to any u  V, k

V, k  K a product ku

K a product ku  V.

V.

Then V is called a vector space (over the field K) if the following axioms hold for any vectors u; v; w  V:

V:

There is a vector in V, denoted by 0 and called the zero vector, such that, for any u

There is a vector in V, denoted by 0 and called the zero vector, such that, for any u  V;

V;

For each u

For each u  V; there is a vector in V, denoted by -u, and called the negative of u, such that

V; there is a vector in V, denoted by -u, and called the negative of u, such that

u + (-u) (-u) + u = 0

The above axioms naturally split into two sets (as indicated by the labeling of the axioms). The first four are concerned only with the additive structure of V and can be summarized by saying V is a commutative group under addition.

This means

(a) Any sum v1 + v2 +……+vm of vectors requires no parentheses and does not depend on the order of the summands.

(b) The zero vector 0 is unique, and the negative -u of a vector u is unique.

(c) (Cancellation Law) If u + w = v + w, then u = v.

Also, subtraction in V is defined by u - v = u + (-v), where -v is the unique negative of v.

Theorem: Let V be a vector space over a field K.

(i) For any scalar k  K and 0

K and 0  V; k0 = 0.

V; k0 = 0.

(ii) For 0  K and any vector u

K and any vector u  V; 0u = 0.

V; 0u = 0.

(iii) If ku = 0, where k  K and u

K and u  V, then k = 0 or u = 0.

V, then k = 0 or u = 0.

(iv) For any k  K and any u

K and any u  V; (-k)u = k(-u) = -ku.

V; (-k)u = k(-u) = -ku.

Examples of Vector Spaces:

Space  Let K be an arbitrary field. The notation

Let K be an arbitrary field. The notation  is frequently used to denote the set of all n-tuples of elements in K. Here

is frequently used to denote the set of all n-tuples of elements in K. Here  is a vector space over K using the following operations:

is a vector space over K using the following operations:

(i) Vector Addition:

(a1, a2, . . . an) + (b1 , b2, . . ., bn) = (a1 + b1, a2 + b2 , . . . an + bn)

(ii) Scalar Multiplication

k(a1, a2, . . ., an) = (ka1, ka2, . . . Kan)

The zero vector in  is the n-tuple of zeros

is the n-tuple of zeros

0 = (0,0,…,0)

And the negative of a vector is defined by

-(a1, a2, . . . , an) = ( - a1, - a2, . . . , - an)

Polynomial Space P(t):

Let P(t) denote the set of all polynomials of the form

p(t) = a0 + a1t + a2t2 + . . . + asts (s = 1, 2, . . .)

Where the coefficients ai belong to a field K. Then PðtÞ is a vector space over K using the following operations:

(i) Vector Addition: Here p(t)+ q(t) in P(t) is the usual operation of addition of polynomials.

(ii) Scalar Multiplication: Here kp(t) in P(t) is the usual operation of the product of a scalar k and a polynomial p(t). The zero polynomial 0 is the zero vector in P(t)

Function Space F(X):

Let X be a nonempty set and let K be an arbitrary field. Let F(X) denote the set of all functions of X into K. [Note that F(X) is nonempty, because X is nonempty.] Then F(X) is a vector space over K with respect to the following operations:

(i) Vector Addition: The sum of two functions f and g in F(X) is the function f + g in F(X) defined by

(f +g)(x) = f(x) + g(x) ∀ x ∈ X

(ii) Scalar Multiplication: The product of a scalar k belongs to K and a function f in F(X) is the function kf in F(X) defined by

(kf)(x) = kf(x) ∀ x ∈ X

The zero vector in F(X) is the zero function 0, which maps every x belngs to X into the zero element 0 belongs to K;

0(x) = 0 ∀ x ∈ X

Also, for any function f in F(X), negative of f is the function -f in F(X) defined by

(-f)(x) = - f(x) ∀ x ∈ X

Fields and Subfields

Suppose a field E is an extension of a field K; that is, suppose E is a field that contains K as a subfield. Then E may be viewed as a vector space over K using the following operations:

(i) Vector Addition: Here u + v in E is the usual addition in E.

(ii) Scalar Multiplication: Here ku in E, where k  K and u

K and u  E, is the usual product of k and u as elements of E.

E, is the usual product of k and u as elements of E.

Vector-

An ordered n – tuple of numbers is called an n – vector. Thus the ‘n’ numbers x1, x2, …………xn taken in order denote the vector x. i.e. x = (x1, x2, ……., xn).

Where the numbers x1, x2, ………..,xn are called component or co – ordinates of a vector x. A vector may be written as row vector or a column vector.

If A be an mxn matrix then each row will be an n – vector & each column will be an m – vector.

Linear dependence-

A set of n – vectors. x1, x2, …….., xr is said to be linearly dependent if there exist scalars. k1, k2, …….,kr not all zero such that

k1 + x2k2 + …………….. + xrkr = 0 … (1)

Linear independence-

A set of r vectors x1, x2, ………….,xr is said to be linearly independent if there exist scalars k1, k2, …………, kr all zero such that

x1 k1 + x2 k2 + …….. + xrkr = 0

Important notes-

- Equation (1) is known as a vector equation.

- If the vector equation has non – zero solution i.e. k1, k2, ….,kr not all zero. Then the vector x1, x2, ……….xr are said to be linearly dependent.

- If the vector equation has only trivial solution i.e.

k1 = k2 = …….=kr = 0. Then the vector x1, x2, ……,xr are said to linearly independent.

Linear combination-

A vector x can be written in the form.

x = x1 k1 + x2 k2 + ……….+xrkr

Where k1, k2, ………….., kr are scalars, then X is called linear combination of x1, x2, ……, xr.

Results:

- A set of two or more vectors are said to be linearly dependent if at least one vector can be written as a linear combination of the other vectors.

- A set of two or more vector are said to be linearly independent then no vector can be expressed as linear combination of the other vectors.

Linear spans:

Suppose  are any vectors in a vector space V. Recall that any vector of the form

are any vectors in a vector space V. Recall that any vector of the form  , where the ai are scalars, is called a linear combination of

, where the ai are scalars, is called a linear combination of  .

.

The collection of all such linear combinations, denoted by Span( or span(

or span( Clearly the zero vector 0 belongs to span

Clearly the zero vector 0 belongs to span , because

, because

0 = 0u1 + 0u2 + . . . + 0um

Furthermore, suppose v and v’ belong to span ,, say,

,, say,

v = a1u1 + a2u2 + . . . + amum and v’ =b1u1 + b2u2 + . . . + bmum

Then

v + v’ = (a1 + b1)u1 + (a2 + b2)u2 + . . . + (am + bm)um

And, for any scalar k belongs to K,

Kv = ka1u1 + ka2u2 + . . . + kamum

Thus, v + v’ and kv also belong to span . Accordingly, span

. Accordingly, span is a subspace of V.

is a subspace of V.

Spanning sets:

Let V be a vector space over K. Vectors  in V are said to span V or to form a spanning set of V if every v in V is a linear combination of the vectors

in V are said to span V or to form a spanning set of V if every v in V is a linear combination of the vectors  —that is, if there exist scalars

—that is, if there exist scalars  in K such that

in K such that

v = a1u1 + a2u2 + . . . + amum

Note-

- Suppose

span V. Then, for any vector w, the set w;

span V. Then, for any vector w, the set w;  also spans V.

also spans V. - Suppose

span V and suppose uk is a linear combination of some of the other u’s. Then the u’s without

span V and suppose uk is a linear combination of some of the other u’s. Then the u’s without  also span V.

also span V. - Suppose

span V and suppose one of the u’s is the zero vector. Then the u’s without the zero vector also span V.

span V and suppose one of the u’s is the zero vector. Then the u’s without the zero vector also span V.

Example: Let consider a vector space V =

(a) We claim that the following vectors form a spanning set of

c1 = (1, 0, 0), c2 = (0, 1, 0) c3 = (0, 0, 1)

Specifically, if v = (a b c) is any vector in  , then

, then

v = ae1 + be2 + ce3

For example,

v = (5, -6, 2) = -5e1 – 6e2 + 2e3

(b) We claim that the following vectors also form a spanning set of

w1 = (1, 1, 1), w2 = (1, 1, 0), w3 = (1, 0, 0)

Specifically, if v = (a b c) is any vector in  , then

, then

v = (a, b, c) = cw1 + (b – c)w2 + (a-b)w3

For example,

v = (5, -6, 2) = 2w1 – 8w2 + 11w3

Example: Consider the vector space M =  consisting of all 2 by 2 matrices, and consider the following four matrices in M:

consisting of all 2 by 2 matrices, and consider the following four matrices in M:

Then clearly any matrix A in M can be written as a linear combination of the four matrices. For example,

Accordingly, the four matrices  span M.

span M.

Unit - 2

Linear algebra

Unit - 2

Linear algebra

We define a vector space V where K is the field of scalars as follows-

Let V be a nonempty set with two operations-

(i) Vector Addition: This assigns to any u; v  V a sum u + v in V.

V a sum u + v in V.

(ii) Scalar Multiplication: This assigns to any u  V, k

V, k  K a product ku

K a product ku  V.

V.

Then V is called a vector space (over the field K) if the following axioms hold for any vectors u; v; w  V:

V:

There is a vector in V, denoted by 0 and called the zero vector, such that, for any u

There is a vector in V, denoted by 0 and called the zero vector, such that, for any u  V;

V;

For each u

For each u  V; there is a vector in V, denoted by -u, and called the negative of u, such that

V; there is a vector in V, denoted by -u, and called the negative of u, such that

u + (-u) (-u) + u = 0

The above axioms naturally split into two sets (as indicated by the labeling of the axioms). The first four are concerned only with the additive structure of V and can be summarized by saying V is a commutative group under addition.

This means

(a) Any sum v1 + v2 +……+vm of vectors requires no parentheses and does not depend on the order of the summands.

(b) The zero vector 0 is unique, and the negative -u of a vector u is unique.

(c) (Cancellation Law) If u + w = v + w, then u = v.

Also, subtraction in V is defined by u - v = u + (-v), where -v is the unique negative of v.

Theorem: Let V be a vector space over a field K.

(i) For any scalar k  K and 0

K and 0  V; k0 = 0.

V; k0 = 0.

(ii) For 0  K and any vector u

K and any vector u  V; 0u = 0.

V; 0u = 0.

(iii) If ku = 0, where k  K and u

K and u  V, then k = 0 or u = 0.

V, then k = 0 or u = 0.

(iv) For any k  K and any u

K and any u  V; (-k)u = k(-u) = -ku.

V; (-k)u = k(-u) = -ku.

Examples of Vector Spaces:

Space  Let K be an arbitrary field. The notation

Let K be an arbitrary field. The notation  is frequently used to denote the set of all n-tuples of elements in K. Here

is frequently used to denote the set of all n-tuples of elements in K. Here  is a vector space over K using the following operations:

is a vector space over K using the following operations:

(i) Vector Addition:

(a1, a2, . . . an) + (b1 , b2, . . ., bn) = (a1 + b1, a2 + b2 , . . . an + bn)

(ii) Scalar Multiplication

k(a1, a2, . . ., an) = (ka1, ka2, . . . Kan)

The zero vector in  is the n-tuple of zeros

is the n-tuple of zeros

0 = (0,0,…,0)

And the negative of a vector is defined by

-(a1, a2, . . . , an) = ( - a1, - a2, . . . , - an)

Polynomial Space P(t):

Let P(t) denote the set of all polynomials of the form

p(t) = a0 + a1t + a2t2 + . . . + asts (s = 1, 2, . . .)

Where the coefficients ai belong to a field K. Then PðtÞ is a vector space over K using the following operations:

(i) Vector Addition: Here p(t)+ q(t) in P(t) is the usual operation of addition of polynomials.

(ii) Scalar Multiplication: Here kp(t) in P(t) is the usual operation of the product of a scalar k and a polynomial p(t). The zero polynomial 0 is the zero vector in P(t)

Function Space F(X):

Let X be a nonempty set and let K be an arbitrary field. Let F(X) denote the set of all functions of X into K. [Note that F(X) is nonempty, because X is nonempty.] Then F(X) is a vector space over K with respect to the following operations:

(i) Vector Addition: The sum of two functions f and g in F(X) is the function f + g in F(X) defined by

(f +g)(x) = f(x) + g(x) ∀ x ∈ X

(ii) Scalar Multiplication: The product of a scalar k belongs to K and a function f in F(X) is the function kf in F(X) defined by

(kf)(x) = kf(x) ∀ x ∈ X

The zero vector in F(X) is the zero function 0, which maps every x belngs to X into the zero element 0 belongs to K;

0(x) = 0 ∀ x ∈ X

Also, for any function f in F(X), negative of f is the function -f in F(X) defined by

(-f)(x) = - f(x) ∀ x ∈ X

Fields and Subfields

Suppose a field E is an extension of a field K; that is, suppose E is a field that contains K as a subfield. Then E may be viewed as a vector space over K using the following operations:

(i) Vector Addition: Here u + v in E is the usual addition in E.

(ii) Scalar Multiplication: Here ku in E, where k  K and u

K and u  E, is the usual product of k and u as elements of E.

E, is the usual product of k and u as elements of E.

Vector-

An ordered n – tuple of numbers is called an n – vector. Thus the ‘n’ numbers x1, x2, …………xn taken in order denote the vector x. i.e. x = (x1, x2, ……., xn).

Where the numbers x1, x2, ………..,xn are called component or co – ordinates of a vector x. A vector may be written as row vector or a column vector.

If A be an mxn matrix then each row will be an n – vector & each column will be an m – vector.

Linear dependence-

A set of n – vectors. x1, x2, …….., xr is said to be linearly dependent if there exist scalars. k1, k2, …….,kr not all zero such that

k1 + x2k2 + …………….. + xrkr = 0 … (1)

Linear independence-

A set of r vectors x1, x2, ………….,xr is said to be linearly independent if there exist scalars k1, k2, …………, kr all zero such that

x1 k1 + x2 k2 + …….. + xrkr = 0

Important notes-

- Equation (1) is known as a vector equation.

- If the vector equation has non – zero solution i.e. k1, k2, ….,kr not all zero. Then the vector x1, x2, ……….xr are said to be linearly dependent.

- If the vector equation has only trivial solution i.e.

k1 = k2 = …….=kr = 0. Then the vector x1, x2, ……,xr are said to linearly independent.

Linear combination-

A vector x can be written in the form.

x = x1 k1 + x2 k2 + ……….+xrkr

Where k1, k2, ………….., kr are scalars, then X is called linear combination of x1, x2, ……, xr.

Results:

- A set of two or more vectors are said to be linearly dependent if at least one vector can be written as a linear combination of the other vectors.

- A set of two or more vector are said to be linearly independent then no vector can be expressed as linear combination of the other vectors.

Linear spans:

Suppose  are any vectors in a vector space V. Recall that any vector of the form

are any vectors in a vector space V. Recall that any vector of the form  , where the ai are scalars, is called a linear combination of

, where the ai are scalars, is called a linear combination of  .

.

The collection of all such linear combinations, denoted by Span( or span(

or span( Clearly the zero vector 0 belongs to span

Clearly the zero vector 0 belongs to span , because

, because

0 = 0u1 + 0u2 + . . . + 0um

Furthermore, suppose v and v’ belong to span ,, say,

,, say,

v = a1u1 + a2u2 + . . . + amum and v’ =b1u1 + b2u2 + . . . + bmum

Then

v + v’ = (a1 + b1)u1 + (a2 + b2)u2 + . . . + (am + bm)um

And, for any scalar k belongs to K,

Kv = ka1u1 + ka2u2 + . . . + kamum

Thus, v + v’ and kv also belong to span . Accordingly, span

. Accordingly, span is a subspace of V.

is a subspace of V.

Spanning sets:

Let V be a vector space over K. Vectors  in V are said to span V or to form a spanning set of V if every v in V is a linear combination of the vectors

in V are said to span V or to form a spanning set of V if every v in V is a linear combination of the vectors  —that is, if there exist scalars

—that is, if there exist scalars  in K such that

in K such that

v = a1u1 + a2u2 + . . . + amum

Note-

- Suppose

span V. Then, for any vector w, the set w;

span V. Then, for any vector w, the set w;  also spans V.

also spans V. - Suppose

span V and suppose uk is a linear combination of some of the other u’s. Then the u’s without

span V and suppose uk is a linear combination of some of the other u’s. Then the u’s without  also span V.

also span V. - Suppose

span V and suppose one of the u’s is the zero vector. Then the u’s without the zero vector also span V.

span V and suppose one of the u’s is the zero vector. Then the u’s without the zero vector also span V.

Example: Let consider a vector space V =

(a) We claim that the following vectors form a spanning set of

c1 = (1, 0, 0), c2 = (0, 1, 0) c3 = (0, 0, 1)

Specifically, if v = (a b c) is any vector in  , then

, then

v = ae1 + be2 + ce3

For example,

v = (5, -6, 2) = -5e1 – 6e2 + 2e3

(b) We claim that the following vectors also form a spanning set of

w1 = (1, 1, 1), w2 = (1, 1, 0), w3 = (1, 0, 0)

Specifically, if v = (a b c) is any vector in  , then

, then

v = (a, b, c) = cw1 + (b – c)w2 + (a-b)w3

For example,

v = (5, -6, 2) = 2w1 – 8w2 + 11w3

Example: Consider the vector space M =  consisting of all 2 by 2 matrices, and consider the following four matrices in M:

consisting of all 2 by 2 matrices, and consider the following four matrices in M:

Then clearly any matrix A in M can be written as a linear combination of the four matrices. For example,

Accordingly, the four matrices  span M.

span M.

First we will go through some important definitions before studying Eigen values and Eigen vectors.

1. Vector-

An ordered n – touple of numbers is called an n – vector. Thus the ‘n’ numbers x1, x2, …………xn taken in order denote the vector x. i.e. x = (x1, x2, ……., xn).

Where the numbers x1, x2, ………..,xn are called component or co – ordinates of a vector x. A vector may be written as row vector or a column vector.

If A be an mxn matrix then each row will be an n – vector & each column will be an m – vector.

2. Linear dependence-

A set of n – vectors. x1, x2, …….., xr is said to be linearly dependent if there exist scalars. k1, k2, …….,kr not all zero such that

k1 + x2k2 + …………….. + xrkr = 0 … (1)

3. Linear independence-

A set of r vectors x1, x2, ………….,xr is said to be linearly independent if there exist scalars k1, k2, …………, kr all zero such that

x1 k1 + x2 k2 + …….. + xrkr = 0

Important notes-

- Equation (1) is known as a vector equation.

- If the vector equation has non – zero solution i.e. k1, k2, ….,kr not all zero. Then the vector x1, x2, ……….xr are said to be linearly dependent.

- If the vector equation has only trivial solution i.e.

k1 = k2 = …….=kr = 0. Then the vector x1, x2, ……,xr are said to linearly independent.

4. Linear combination-

A vector x can be written in the form.

x = x1 k1 + x2 k2 + ……….+xrkr

Where k1, k2, ………….., kr are scalars, then X is called linear combination of x1, x2, ……, xr.

Results:

- A set of two or more vectors are said to be linearly dependent if at least one vector can be written as a linear combination of the other vectors.

- A set of two or more vector are said to be linearly independent then no vector can be expressed as linear combination of the other vectors.

Example 1

Are the vectors x1 = [1, 3, 4, 2], x2 = [1, 3, 4, 2], x3 = [3, -5, 2, 6], linearly dependent. If so, express x1 as a linear combination of the others.

Solution:

Consider a vector equation,

x1k1 + x2k2 + x3k3 = 0

i.e., [1, -3, 4, 2]k1 + [3, -5, 2,6]k2 + [2, -1, 3, 4]k3 = [0, 0, 0, 0]

∴ k1 +3k2 + 2k3 = 0

+3k1 + 5k2 + k3 = 0

4k1 + 2k2 + 3k3 = 0

2k1 + 6k2 + 4k3 =0

Which can be written in matrix form as,

R2 + 3R1, R3 – 4R1, R4 – 2R1

1/14 R2

R3 + 10R2

Here ρ(A) = 2 & no. Of unknown 3. Hence the system has infinite solutions. Now rewrite the questions as,

k1 + 3k2 + 2k3 =0

k2 + ½ k3 =0

Put k3 =t

k2 = -1/2 t and

k1 = -3k2 – 2k3

= - 3 (- ½ t) -2t

= 3/2 t – 2t

= - t/2

Thus k1 = - t/2, k2 = -1/2 t – k3 = t ∀ t ∈ R

i.e., - t/2 × 1 + ( - t/2) x2 + t × 3 = 0

i.e.,- x1/2 – (-x2/2) + x3 = 0

- x1 – x2 + 2 x3 = 0

x1 = - x2 + 2 x3

Since F11k2, k3 not all zero. Hence x1, x2, x3 are linearly dependent.

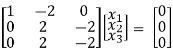

Example 2

Examine whether the following vectors are linearly independent or not.

x1 = [3, 1, 1], x2 = [2, 0, -1] and x3 = [4, 2, 1]

Solution:

Consider the vector equation,

x1k1 + x2k2 + x3k3 = 0

i.e., [3, 1, 1] k1 + [2, 0, -1]k2 + [4, 2, 1]k3 = 0 ...(1)

3k1 + 2k2 + 4k3 = 0

k1 + 2k3 = 0

k1 – k2 + k3 = 0

Which can be written in matrix form as,

R12

R2 – 3R1, R3 – R1

+ ½ R2

R3 + R2

Here Rank of coefficient matrix is equal to the no. Of unknowns. i.e. r = n = 3.

Hence the system has unique trivial solution.

i.e. k1 = k2 = k3 = 0

i.e. vector equation (1) has only trivial solution. Hence the given vectors x1, x2, x3 are linearly independent.

Example 3

At what value of P the following vectors are linearly independent.

[1, 3, 2], [2, P+7, 4], [1, 3, P+3]

Solution:

Consider the vector equation.

[1, 3, 2]k1 + [2, P+7, 4]k2 + [1, 3, P+3]k3 = 0

i.e.

k1 + 2k2 + k3 = 0

3k1 + (p + 7)k2 + 3k3 = 0

2k1 + 4k2 + (P +3)k3 = 0

This is a homogeneous system of three equations in 3 unknowns and has a unique trivial solution.

If and only if Determinant of coefficient matrix is non zero.

consider

consider  .

.

i.e.,

1[(P + λ)(P+3) – 12] – 2[3(P+3) – 6] + 1[12 – (2P + 14)]  0

0

P2 + 10P + 21 – 12 -6P – 6 – 2P – 2

P2 + 2P + 1

(P + 1)2

(P + 1)

P

Thus for  the system has only trivial solution and Hence the vectors are linearly independent.

the system has only trivial solution and Hence the vectors are linearly independent.

Note:-

If the rank of the coefficient matrix is r, it contains r linearly independent variables & the remaining vectors (if any) can be expressed as linear combination of these vectors.

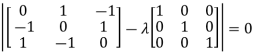

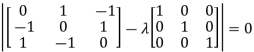

Characteristic equation:

Let A he a square matrix, λ be any scalar then |A – λI| = 0 is called characteristic equation of a matrix A.

Note:

Let a be a square matrix and ‘λ’ be any scalar then,

1) [A – λI] is called characteristic matrix

2) | A – λI| is called characteristic polynomial.

The roots of a characteristic equations are known as characteristic root or latent roots, Eigen values or proper values of a matrix A.

Eigen vector:

Suppose λ1 be an Eigen value of a matrix A. Then ∃ a non – zero vector x1 such that.

[A – λI] x1 = 0 ...(1)

Such a vector ‘x1’ is called as Eigen vector corresponding to the Eigen value λ1

Properties of Eigen values:

- Then sum of the Eigen values of a matrix A is equal to sum of the diagonal elements of a matrix A.

- The product of all Eigen values of a matrix A is equal to the value of the determinant.

- If λ1, λ2, λ3, ..., λn are n Eigen values of square matrix A then 1/λ1, 1/λ2, 1/λ3, ..., 1/λn are m Eigen values of a matrix A-1.

- The Eigen values of a symmetric matrix are all real.

- If all Eigen values are non –zero then A-1 exist and conversely.

- The Eigen values of A and A’ are same.

Properties of Eigen vector:

- Eigen vector corresponding to distinct Eigen values are linearly independent.

- If two are more Eigen values are identical then the corresponding Eigen vectors may or may not be linearly independent.

- The Eigen vectors corresponding to distinct Eigen values of a real symmetric matrix are orthogonal.

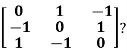

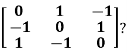

Example1: Find the sum and the product of the Eigen values of  ?

?

Sol. The sum of Eigen values = the sum of the diagonal elements

=1+(-1)=0

=1+(-1)=0

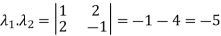

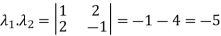

The product of the Eigen values is the determinant of the matrix

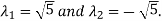

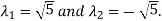

On solving above equations we get

Example2: Find out the Eigen values and Eigen vectors of  ?

?

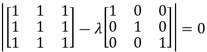

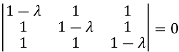

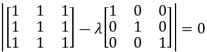

Sol. The Characteristics equation is given by

Or

Hence the Eigen values are 0,0 and 3.

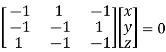

The Eigen vector corresponding to Eigen value  is

is

Where X is the column matrix of order 3 i.e.

This implies that

Here number of unknowns are 3 and number of equation is 1.

Hence we have (3-1) = 2 linearly independent solutions.

Let

Thus the Eigen vectors corresponding to the Eigen value  are (-1,1,0) and (-2,1,1).

are (-1,1,0) and (-2,1,1).

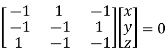

The Eigen vector corresponding to Eigen value  is

is

Where X is the column matrix of order 3 i.e.

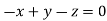

This implies that

Taking last two equations we get

Or

Thus the Eigen vectors corresponding to the Eigen value  are (3,3,3).

are (3,3,3).

Hence the three Eigen vectors obtained are (-1,1,0), (-2,1,1) and (3,3,3).

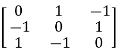

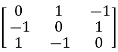

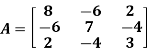

Example3: Find out the Eigen values and Eigen vectors of

Sol. Let A =

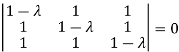

The characteristics equation of A is  .

.

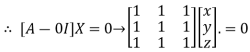

Or

Or

Or

Or

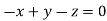

The Eigen vector corresponding to Eigen value  is

is

Where X is the column matrix of order 3 i.e.

Or

On solving we get

Thus the Eigen vectors corresponding to the Eigen value  is (1,1,1).

is (1,1,1).

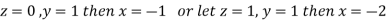

The Eigen vector corresponding to Eigen value  is

is

Where X is the column matrix of order 3 i.e.

Or

On solving  or

or  .

.

Thus the Eigen vectors corresponding to the Eigen value  is (0,0,2).

is (0,0,2).

The Eigen vector corresponding to Eigen value  is

is

Where X is the column matrix of order 3 i.e.

Or

On solving we get  or

or  .

.

Thus the Eigen vectors corresponding to the Eigen value  is (2,2,2).

is (2,2,2).

Hence three Eigen vectors are (1,1,1), (0,0,2) and (2,2,2).

Example-4:

Determine the Eigen values of Eigen vector of the matrix.

Solution:

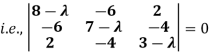

Consider the characteristic equation as, |A – λI| = 0

i.e., (8 – λ) (21 - 10 λ + λ2 – 16) + 6(-18 + 6 λ + 8) + 2(24 – 14 + 2 λ) =0

(8- λ)( λ2 -10 λ + 5) + 6(6 λ – 10) + 2(2 λ + 10) = 0

8 λ2 - 80 λ + 40 – λ3 + 10 λ2 - 5 λ + 36 λ – 60

- λ3 + 18 λ - 45 λ = 0

i.e., λ3 – 18 λ + 45 λ = 0

Which is the required characteristic equation.

λ(λ2 - 18 λ + 45) = 0

λ(λ – 15)( λ – 3) = 0

λ = 0, 15, 3 are the required Eigen values.

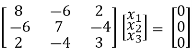

Now consider the equation

[A – λI] x = 0 ...................(1)

Case I:

If λ = 0 Equation (1) becomes

R1 + R2

R2 + 3R1, R3 – R1

-1/1 R2

R3 + 5R2

Thus ρ[A – λI] = 2 & n = 3

3 – 2 = 1 independent variable.

Now rewrite equation as,

2x1 + x2 – 2x3 = 0

x2 – x3 = 0

Put x3 = t

x2 = t &

2x1 = - x2 + 2x3

2x1 = -t + 2t

x1 = t/2

Thus x1 =

Is the eigen vector corresponding to λ = t.

Case II:

If λ = 3 equation (1) becomes,

R1 – 2R3

R2 + 6R1 , R3 – 2R1

½ R2

R3+R2

Here ρ[A – λI] = 2, n = 3

3-2 = 1 Independent variables

Now rewrite the equations as,

x1 + 2x2 + 2x3 = 0

8x2 + 4x3 = 0

Put x3 = t

x2 = ½ t &

x1 = -2x2 – 2x3

= - 2 ( ½ ) t – 2 (t)

= - 3t

x2 =

Is the eigen vector corresponding to λ = 3.

Case III:

If λ = 15 equation (1) becomes,

R1 + 4R3

½ R3

R13

R2 + 6R1 , R3 – R1

R3 – R2

Here rank of [ A – λ I] = 2 & n = 3

3 – 2 = 1 independent variable

Now rewrite the equations as,

x1 – 2x2 – 6x3 = 0

-20x2 – 40x3 =0

Put x3 = t

x2 = - 2t & x1 = 2t

Thus x3 =

Is the eigen vector for λ = 13.

Example-5:

Find the Eigen values of Eigen vector for the matrix.

Solution:

Consider the characteristic equation as |A – λ I| = 0

i.e.,

(8 –  (-3 + 3λ – λ + λ2 – 8) + 8(4 - 4 λ + 6) – 2(-16 + 9 + 3 λ) = 0

(-3 + 3λ – λ + λ2 – 8) + 8(4 - 4 λ + 6) – 2(-16 + 9 + 3 λ) = 0

(8 – λ)( λ2 + 2 λ – 1) + 8(0 - 4 λ) – 2(3 λ – 7) = 0

8 λ2 + 16 λ – 88 – λ3 - 2 λ2 + 11 λ + 80 - 32 λ - 6 λ + 14 = 0

i.e., - λ3 + 6 λ2 - 11 λ + 6 = 0

λ3 - 6 λ2 + 11 λ + 6 = 0

(λ – 1)( λ – 2)( λ – 3) = 0

λ = 1, 2, 3 are the required eigen values

Now consider the equation

[A – λI] x = 0 ..............(1)

Case I:

λ = 1 Equation (1) becomes,

R1 – 2R3

R2 – 4R1, R3 – 3R1

R3 – R2

Thus ρ[A – λI] = 2 and n = 3

3 – 2 = 1 independent variables

Now rewrite the equations as,

x1 – 2x3 = 0

-4x2 + 6x3 = 0

Put x3= t

x2 = 3/2 t , x1 = 2b

x1 =

I.e.

The Eigen vector for

Case II:

If λ = 2 equation (1) becomes,

1/6 R1

R2 – 4R1, R3 – 3 R1

Thus ρ(A – λI) = 2 & n = 3

3 – 2 = 1

Independent variables.

Now rewrite the equations as,

x1 – 4/3 x2 – 1/3 x3 = 0

1/3 x2 + 2/3 x3 = 0

Put x3 = t

1/3 x2 = - 2/3 t

x2 = -2t

x1 = - 4/3 x2 + 1/3 x3

= (-4)/3 (-2t) + 1/3 t

= 3t

X2 =

Is the Eigen vector for λ = 2

Now

Case III:

If λ = 3 equation (1) gives,

R1 – R2

R2 – 4R1, R3 – 3R1

R3 – R2

Thus ρ[A – λI] = 2 & n = 3

3 – 2 = 1

Independent variables

Now x1 – 2x2 = 0

2x2 – 2x3 = 0

Put x3 = t, x2 = t, x1 = 25

Thus

x3 =

Is the Eigen vector for λ = 3

Rayleigh's power method-

Suppose x be an eigen vector of A. Then the eigen value  corresponding to this eigen vector is given as-

corresponding to this eigen vector is given as-

This quotient is called Rayleigh’s quotient.

Proof:

Here x is an eigen vector of A,

As we know that  ,

,

We can write-

Diagonalization of a square matrix of order two

Two square matrix  and A of same order n are said to be similar if and only if

and A of same order n are said to be similar if and only if

for some non singular matrix P.

for some non singular matrix P.

Such transformation of the matrix A into  with the help of non singular matrix P is known as similarity transformation.

with the help of non singular matrix P is known as similarity transformation.

Similar matrices have the same Eigen values.

If X is an Eigen vector of matrix A then  is Eigen vector of the matrix

is Eigen vector of the matrix

Reduction to Diagonal Form:

Let A be a square matrix of order n has n linearly independent Eigen vectors Which form the matrix P such that

Where P is called the modal matrix and D is known as spectral matrix.

Procedure: let A be a square matrix of order 3.

Let three Eigen vectors of A are  Corresponding to Eigen values

Corresponding to Eigen values

Let

{by characteristics equation of A}

{by characteristics equation of A}

Or

Or

Note: The method of diagonalization is helpful in calculating power of a matrix.

.Then for an integer n we have

.Then for an integer n we have

We are using the example of 1.6*

Example1: Diagonalise the matrix

Let A=

The three Eigen vectors obtained are (-1,1,0), (-1,0,1) and (3,3,3) corresponding to Eigen values  .

.

Then  and

and

Also we know that

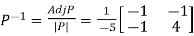

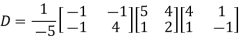

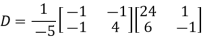

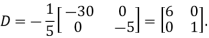

Example2: Diagonalise the matrix

Let A =

The Eigen vectors are (4,1),(1,-1) corresponding to Eigen values  .

.

Then  and also

and also

Also we know that

Singular value decomposition:

The singular value decomposition of a matrix is usually referred to as the SVD. This is the final and best factorization of a matrix

Where U is orthogonal, Σ is diagonal, and V is orthogonal.

In the decomoposition

A can be any matrix. We know that if A is symmetric positive definite its eigenvectors are orthogonal and we can write A = QΛ . This is a special case of a SVD, with U = V = Q. For more general A, the SVD requires two different matrices U and V. We’ve also learned how to write A = SΛ

. This is a special case of a SVD, with U = V = Q. For more general A, the SVD requires two different matrices U and V. We’ve also learned how to write A = SΛ , where S is the matrix of n distinct eigenvectors of A. However, S may not be orthogonal; the matrices U and V in the SVD will be

, where S is the matrix of n distinct eigenvectors of A. However, S may not be orthogonal; the matrices U and V in the SVD will be

Working of SVD:

We can think of A as a linear transformation taking a vector v1 in its row space to a vector u1 = Av1 in its column space. The SVD arises from finding an orthogonal basis for the row space that gets transformed into an orthogonal basis for the column space: Avi = σiui. It’s not hard to find an orthogonal basis for the row space – the Gram Schmidt process gives us one right away. But in general, there’s no reason to expect A to transform that basis to another orthogonal basis. You may be wondering about the vectors in the null spaces of A and  . These are no problem – zeros on the diagonal of Σ will take care of them.

. These are no problem – zeros on the diagonal of Σ will take care of them.

Matrix form:

The heart of the problem is to find an orthonormal basis v1, v2, ...vr for the row space of A for which

A[ v1 v2 ... vr] = [ σ1u1 σ2u2 . . . σrur] = [ u1 u2 . . . ur]

With u1, u2, ...ur an orthonormal basis for the column space of A. Once we add in the null spaces, this equation will become AV = UΣ. (We can complete the orthonormal bases v1, ...vr and u1, ...ur to orthonormal bases for the entire space any way we want. Since  , ...

, ... will be in the null space of A, the diagonal entries

will be in the null space of A, the diagonal entries  , ...

, ... will be 0.) The columns of U and V are bases for the row and column spaces, respectively. Usually U is not equal to V, but if A is positive definite we can use the same basis for its row and column space.

will be 0.) The columns of U and V are bases for the row and column spaces, respectively. Usually U is not equal to V, but if A is positive definite we can use the same basis for its row and column space.

Sylvester theorem: Let A be the matrix of a symmetric bilinear form, of a finite dimenasional vector space, with respect to an orthogonal basis. Then the number of 1’s and -1’s and 0’s is independent of the choice of orthogonal basis.

Proof:

Let {e1, . . . , en} be an orthogonal basis of V such that the diagonal matrix A representing the form has only 1, -1 and 0 on the diagonal. By permuting the basis we can furthermore assume that the first p basis vectors are such that hei , eii = 1, the m next vectors give -1, and the final s = n − (p + m) vectors produce the zeros. It follows that s = n − (p + m) is the dimension of the null-space AX = 0. Therefore the number s = n − (p + m) of zeros on the diagonal is unique. Assume that we have found another orthogonal basis of V such that the diagonal matrix representing the form has first p 0 diagonal elements equal to 1, next m0 diagonal elements equal to -1, and the remaining s = n−(p 0 +m0 ) diagonal elements are zero. Let {f1, . . . , fn} be such a basis. We then claim that the p + m0 vectors e1, . . . , ep, fp 0+1, . . . , fp 0+m0 are linearly independent. Assume the converse, that there is a linear relation between these vectors.

Such a relation we can split as

..........................(1)

..........................(1)

The vector occurring on the left hand side we call X. We have that

The vector X also occurs on the right hand side of (1), and gives that

These two expressions for the number hX, Xi implies that b1 = · · · = bp = 0 and that cp 0+1 = · · · = cp 0+m0 = 0. In other words we have proven tha

The p+ m0 vectors e1, . . . , ep, fp 0+1, . . . , fp 0+m0 are linearly independent. Their total number can not exceed s which gives p+m0 ≤ s. Thus p ≤ p 0 . However, the argument presented is symmetric, and we can interchange the role of p 0 and p, from where it follows that p = p 0 . Thus the number of 1’s is unique. It then follows that also the number of -1’s is unique.

The pair (p, m) where p is the number of 1’s and m is the number of -1’s is called the signature of the form. To a given signature (p, m) we have the diagonal (n × n)-matrix Ip,m whose first p diagonal elements are 1, next m diagonal elements are -1, and the remaining diagonal (n − p − m) elements are 0.

Examples:

- Let V be the vector space of real (2 × 2)-matrices. (a) Show that the form hA, Bi = det(A + B) − det(A) − det(B) is symmetric and bilinear. (b) Compute the matrix A representing the above form with respect to the standard basis {E11, E12, E21, E22}, and determine the signature of the form. (c) Let W be the sub-vector space of V consisting of trace zero matrices. Compute the signature of the form discribed above, restricted to W.

- 2. Determine the signature of the form hA, Bi = Trace(AtrB) on the space of real (n × n)-matrices.

Rayleigh's power method-

Suppose x be an eigen vector of A. Then the eigen value  corresponding to this eigen vector is given as-

corresponding to this eigen vector is given as-

This quotient is called Rayleigh’s quotient.

Proof:

Here x is an eigen vector of A,

As we know that  ,

,

We can write-

Gauss-Seidel iteration method-

Step by step method to solve the system of linear equation by using Gauss Seidal Iteration method-

Suppose,

This system can be written as after dividing it by suitable constants,

Step-1 Here put y = 0 and z = 0 and x =  in first equation

in first equation

Then in second equation we put this value of x that we get the value of y.

In the third eq. We get z by using the values of x and y

Step-2: we repeat the same procedure

Example: solve the following system of linear equations by using Guass seidel method-

6x + y + z = 105

4x + 8y + 3z = 155

5x + 4y - 10z = 65

Sol. The above equations can be written as,

………………(1)

………………(1)

………………………(2)

………………………(2)

………………………..(3)

………………………..(3)

Now put z = y = 0 in first eq.

We get

x = 35/2

Put x = 35/2 and z = 0 in eq. (2)

We have,

Put the values of x and y in eq. 3

Again start from eq.(1)

By putting the values of y and z

y = 85/8 and z = 13/2

We get

The process can be showed in the table format as below

At the fourth iteration, we get the values of x = 14.98, y = 9.98 , z = 4.98

Which are approximately equal to the actual values,

As x = 15, y = 10 and y = 5 ( which are the actual values)

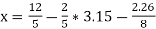

Example: Solve the following system of linear equations by using Gauss-seidel method-

5x + 2y + z = 12

x + 4y + 2z = 15

x + 2y + 5z = 20

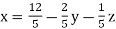

Sol. These equations can be written as,

………………(1)

………………(1)

………………………(2)

………………………(2)

………………………..(3)

………………………..(3)

Put y and z equals to 0 in eq. 1

We get,

x = 2.4

Put x = 2.4, and z = 0 in eq. 2 , we get

Put x = 2.4 and y = 3.15 in eq.(3) , we get

Again start from eq.(1), put the values of y and z , we get

= 0.688

= 0.688

We repeat the process again and again,

The following table can be obtained –

Here we see that the values are approx. Equal to exact values.

Exact values are, x = 1, y = 2, z = 3.

References:

- E. Kreyszig, “Advanced Engineering Mathematics”, John Wiley & Sons, 2006.

- P. G. Hoel, S. C. Port And C. J. Stone, “Introduction To Probability Theory”, Universal Book Stall, 2003.

- S. Ross, “A First Course in Probability”, Pearson Education India, 2002.

- W. Feller, “An Introduction To Probability Theory and Its Applications”, Vol. 1, Wiley, 1968.

- N.P. Bali and M. Goyal, “A Text Book of Engineering Mathematics”, Laxmi Publications, 2010.

- B.S. Grewal, “Higher Engineering Mathematics”, Khanna Publishers, 2000.