Unit - 5

Stochastic process and sampling techniques

A stochastic process is a collection of random variables that take values in a set S, the state space.

The collection is indexed by another set T, the index set. The two most common index sets are the natural numbers T = {0, 1, 2, ...}, and the nonnegative real numbers

T = [0,∞), which usually represent discrete time and continuous time, respectively.

The first index set thus gives a sequence of random variables {X0,X1,X2, ...} andthe second, a collection of random variables {X(t), t ≥ 0}, one random variable for each time t. In general, the index set does not have to describe time but is also commonly used to describe spatial location. The state space can be finite, countably infinite, or uncountable, depending on the application.

In order to be able to analyze a stochastic process, we need to make assumptions on the dependence between the random variables. In this chapter, we will focus on the most common dependence structure, the so called Markov property, and in the next section we give a definition and several examples.

Stochastic process-

Stochastic process is a family of random variables {X(t )|t ∈T } defined on a common sample space S and indexed by the parameter t , which varies on an index set T .

The values assumed by the random variables X(t)are called states, and the set of all possible values from the state space of the process is denoted by I .

If the state space is discrete, the stochastic process is known as a chain.

A stochastic process consists of a sequence of experiments in which each experiment has a finite number of outcomes with given probabilities.

Probability vector-

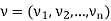

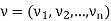

Probability vector is a vector-

If  for every ‘i’ and

for every ‘i’ and

Stochastic matrices-

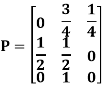

All the entries of square matrix P are non-negative and the sum of the entries of any row is one.

A vector v is said to be a fixed vector or a fixed point of a matrix A if vA= v and v = 0.

If v is a fixed vector of A, so is kv since

(kv)A = k(vA) = k(v) = kv.

Note-

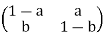

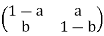

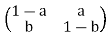

- If v = (v1v2v3) is a probability vector of a stochastic matrix- P =

then vP is also a probability vector.

then vP is also a probability vector. - If P and Q are stochastic matrices then their product P Q is also stochastic matrix. Thus

is stochastic matrix for all positive integer values of n.

is stochastic matrix for all positive integer values of n. - The transition matrix P of a Markov chain is a stochastic matrix.

Example: Which vectors are probability vectors?

- (5/2, 0, 8/3, 1/6, 1/6)

- (3, 0, 2, 5, 3)

Sol.

- It is not a probability vector because the sum of the components do not add up to 1

- Dividing by 3 + 0 + 2 + 5 + 3 = 13, we get the probability vector

(3/13, 0, 2/13, 5/13, 3/13)

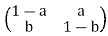

Example: show that  = (b a) is a fixed point of the stochastic matrix-

= (b a) is a fixed point of the stochastic matrix-

P =

Sol.

v P = (b a)

(b – ab + ab ba + a – ab) = (b a) = v

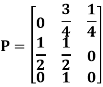

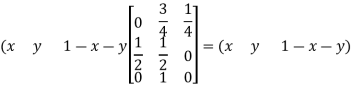

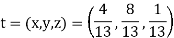

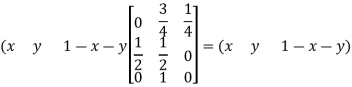

Example: Find the unique fixed probability vector t of

Sol.

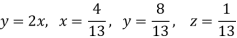

Suppose t = (x, y, z) be the fixed probability vector.

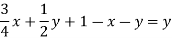

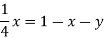

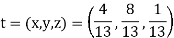

By definition x + y + z = 1. Sot = (x, y,

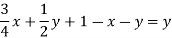

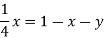

1 −x −y), t is said to be fixed vector, if t P = t

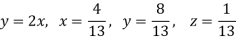

On solving, we get-

Required fixed probability vector is-

Markov chain-

Let X0,X1,X2, ... Be a sequence of discrete random variables,t aking values in some set S and that are such that

P(Xn+1 = j | X0 = i0, . . . , Xn-1 = in-1, Xn = i) = P(Xn+1 = j|Xn = i)

For all i, j, i0, ..., in−1 in S and all n. The sequence {Xn} is then called a Markov chain

We often think of the index n as discrete time and say that Xni s the state of the chain at time n, where the state space S may be finite or countably infinite. The defining property is called the Markov property, which can be stated in words as “conditioned on the present, the future is independent of the past”. In general, the probability P(Xn+1 = j|Xn= i) depends on i, j, and n. It is, however, often the case (as in our roulette example) that there is no dependence on

n. We call such chains time-homogeneous and restrict our attention to these chains. Since the conditional probability in the definition thus depends only on I and j, we use the notation\

pij = P(Xn+1 = j | Xn = j), i, j ∈ S

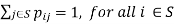

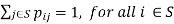

And call these the transition probabilities of the Markov chain. Thus, if the chain is in state i, the probabilities pij describe how the chain chooses which state to jump to next. Obviously the transition probabilities have to satisfy the following two criteria:

(a) pij ≥ 0, for all I, j ∈ S, (b)

Classification of States:

The graphic representation of a Markov chain illustrates in which ways states can be reached from each other. In the roulette example, state 1 can, for example, reach state 2 in one step and state 3, in two steps. It can also reach state 3 in four steps, through the sequence 2, 1, 2, 3, and so on. One important property of state 1 is that it can reach any other state. Compare this to state 0 which cannot reach any other state. Whether or not states can reach each other in this way is of fundamental importance in the study of Markov chains, and we state the following definition.

Def: If pij(n) > 0 for some n, we say that state j is accessible from state i, written i→ j. If i→ j and j → i, we say that I and j communicate and write this i↔ j.

If j is accessible from i, this means that it is possible to reach j from I but not that this necessarily happens. In the roulette example, 1 → 2 since p12 >0, but if the chain starts in 1, it may jump directly to 0, and thus it will never be able to visit state 2. In this example, all nonzero states communicate with each other and 0 communicates only with itself.

In general, if we fix a state I in the state space of a Markov chain, we can find all states that communicate with I and form the communicating class containing i. It is easy to realize that not only does I communicate with all states in this class but they all communicate with each other. By convention, every state communicates with itself

(it can “reach itself in 0 steps”) so every state belongs to a class. If you wish to be more mathematical, the relation “↔” is an equivalence relation and thus divides the state space into equivalence classes that are precisely the communicating classes. In the roulette example, there are two classes

C0 = {0}, C1 = {1, 2, ...}

And in the genetics example, each state forms its own class and we thus have

C1 = {AA}, C2 = {Aa}, C3 = {aa}

In the ON/OFF system, there is only one class, the entire state space S. In this chain, all states communicate with each other, and it turns out that this is a desirable property.

Definition If all states in S communicate with each other, the Markov chain is said to be irreducible

Another important property of Markov chains has to do with returns to a state. For example, in the roulette example, if the chain starts in state 1, it may happen that it never returns. Compare this with the ON/OFF system where the chain eventually returns to where it started (assuming that p >0 and q >0). We next classify states according to whether return is certain. We introduce the notation Pi for the probability distribution of the chain when the initial state X0 is i.

Def: Consider a state i∈ S and let τ i be the number of steps it takes for the chain to first visit i. Thus

Ti = min { n ≥ 1 : Xn = i}

Where τi= ∞ if I is never visited. If Pi(τi<∞) = 1, state I is said to be recurrent and if Pi(τ i<∞) <1, it is said to be transient A recurrent state thus has the property that if the chain starts in it, the time until it returns is finite. For a transient state, there is a positive probability that the time until return is infinite, meaning that the state is never revisited. This means that a recurrent state is visited over and over but a transient state is eventually never revisited. Now consider a transient state I and another state j such that i↔ j. We will argue that j must also be transient. By the Markov property, every visit to j starts afresh Markov chain and since i↔ j, there is a positive probability to visit I before coming back to j. We may think of this as repeated trials to reach I every time the chain is in j, and since the success probability is positive, eventually there will be a success. If j were recurrent, the chain would return to j infinitely many times and the trial would also succeed infinitely many times. But this means that there would be infinitely many visits to i, which is impossible since i is transient. Hence j must also be transient.

We have argued that transience (and hence also recurrence) is a class property, a property that is shared by all states in a communicating class. In particular, the following holds.

Note- In an irreducible Markov chain, either all states are transient or all states are recurrent.

The Simple Random Walk:

Many of the examples we looked at in the previous section are similar in nature.

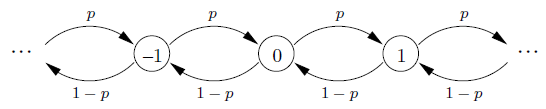

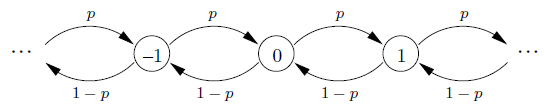

For example, the roulette example and the various versions of gambler’s ruin have in common that the states are integers and the only possible transitions are one step up or one step down. We now take a more systematic look at such Markov chains, called simple random walks. A simple random walk can be described as a Markov chain {Sn} that is such that

Where the Xk are i.i.d. Such that P(Xk= 1) = p, P(Xk= −1) = 1 − p.

The term “simple” refers to the fact that only unit steps are possible; more generally we could let the Xk have any distribution on the integers. The initial state S0 is usually fixed but could also be chosen according to some probability distribution.

Unless otherwise mentioned, we will always have S0 ≡ 0. If p = 1/2, the walk is said to be symmetric. It is clear from the construction that the random walk is a Markov chain with state space S = {...,−2,−1, 0, 1, 2, ...} and transition graph

Note how the transition probabilities pi,i+1 and pi,i−1 do not depend on i, a property called spatial homogeneity. We can also illustrate the random walk as a function of time, as was done in Example. Note that this illustrates one particular outcome of the sequence S0, S1, S2, ..., called a sample path, or a realization, of the random walk.

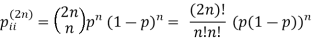

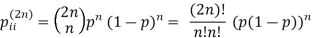

It is clear that the random walk is irreducible, so it has to be either transient, null recurrent, or positive recurrent, and which one it is may depend on p. The random walk is a Markov chain where we can compute the n-step transition probabilities explicitly

pij(2n – 1) = 0 , n = 1, 2, . . .

Since we cannot make it back to a state in an odd number of steps. To make it back in 2n steps, we must take n steps up and n steps down, which has probability

And since convergence of the sum of the  is not affected by the values of any finite number of terms in the beginning, we can use an asymptotic approximation of n!, Stirling’s formula, which says that

is not affected by the values of any finite number of terms in the beginning, we can use an asymptotic approximation of n!, Stirling’s formula, which says that

n! ~ nn √ne-n √2π

Where “∼” means that the ratio of the two sides goes to 1 as n → ∞. The practical use is that we can substitute one for the other for large n in the sum in Pii(2n) ~ (4p(1 – p))n/ √πn and if p = 1/2 , this equals 1/√πn and the sum over n is infinite.

Population-

The population is the collection or group of observations under study.

The total number of observations in a population is known as population size and it is denoted by N.

Types of population-

- Finite population – the population contains finite numbers of observations is known as finite population

- Infinite population- it contains infinite number of observations.

- Real population- the population which comprises the items which are all present physically is known as real population.

- Hypothetical population- if the population consists the items which are not physically present but their existence can be imagined, is known as hypothetical population.

Sample –

To get the information from all the elements of a large population may be time consuming and difficult. And also if the elements of population are destroyed under investigation then getting the information from all the units is not make a sense. For example, to test the blood, doctors take very small amount of blood. Or to test the quality of certain sweet we take a small piece of sweet. In such situations, a small part of population is selected from the population which is called a sample

Complete survey-

When each and every element of the population is investigated or studied for the characteristics under study then we call it complete survey or census.

Sample Survey-

When only a part or a small number of elements of population are investigated or studied for the characteristics under study then we call it sample survey or sample enumeration Simple Random Sampling or Random Sampling

The simplest and most common method of sampling is simple random sampling. In simple random sampling, the sample is drawn in such a way that each element or unit of the population has an equal and independent chance of being included in the sample. If a sample is drawn by this method then it is known as a simple random sample or random sample

Simple Random Sampling without Replacement (SRSWOR)

In simple random sampling, if the elements or units are selected or drawn one by one in such a way that an element or unit drawn at a time is not replaced back to the population before the subsequent draws is called SRSWOR.

Suppose we draw a sample from a population, the size of sample is n and the size of population is N, then total number of possible sample is NCn

Simple Random Sampling with Replacement (SRSWR)

In simple random sampling, if the elements or units are selected or drawn one by one in such a way that a unit drawn at a time is replaced back to the population before the subsequent draw is called SRSWR.

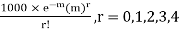

Suppose we draw a sample from a population, the size of sample is n and the size of population is N, then total number of possible sample is  .

.

Parameter-

A parameter is a function of population values which is used to represent the certain characteristic of the population. For example, population mean, population variance, population coefficient of variation, population correlation coefficient, etc. are all parameters. Population parameter mean usually denoted by μ and population variance denoted by

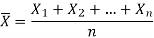

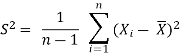

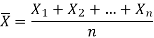

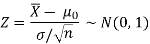

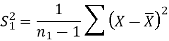

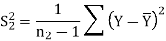

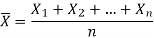

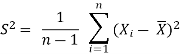

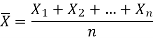

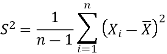

Sample mean and sample variance-

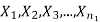

Let  be a random sample of size n taken from a population whose pmf or pdf function f(x,

be a random sample of size n taken from a population whose pmf or pdf function f(x,

Then the sample mean is defined by-

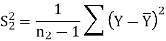

And sample variance-

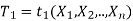

Statistic-

Any quantity which does not contain any unknown parameter and calculated from sample values is known as statistic.

Suppose  is a random sample of size n taken from a population with mean μ and variance

is a random sample of size n taken from a population with mean μ and variance  then the sample mean-

then the sample mean-

Is a statistic.

Estimator and estimate-

If a statistic is used to estimate an unknown population parameter then it is known as estimator and the value of the estimator based on observed value of the sample is known as estimate of parameter.

Standard error-

The standard deviation of the sampling distribution is known as standard error.

When we increase the sample size then standard increases.

It plays an important role in large sample theory.

Note- The reciprocal of the standard error is called ‘precision’.

If the size of the sample is less than 30, it is considered as small sample otherwise it is called large sample.

The sampling distribution of large samples is assumed to be normal.

Key takeaways-

- Population-

The population is the collection or group of observations under study.

2. Simple Random Sampling without Replacement (SRSWOR)

If the elements or units are selected or drawn one by one in such a way that an element or unit drawn at a time is not replaced back to the population before the subsequent draws is called SRSWOR.

Simple Random Sampling with Replacement (SRSWR)

If the elements or units are selected or drawn one by one in such a way that a unit drawn at a time is replaced back to the population before the subsequent draw is called SRSWR.

Statistic-

Any quantity which does not contain any unknown parameter and calculated from sample values is known as statistic.

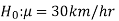

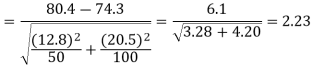

Hypothesis-

A hypothesis is a statement or a claim or an assumption about thev alue of a population parameter.

Similarly, in case of two or more populations a hypothesis is comparative statement or a claim or an assumption about the values of population parameters.

For example-

If a customer of a car wants to test whether the claim of car of a certain brand gives the average of 30km/hr is true or false.

Simple and composite hypotheses-

If a hypothesis specifies only one value or exact value of the population parameter then it is known as simple hypothesis. And if a hypothesis specifies not just one value but a range of values that the population parameter may assume is called a composite hypothesis.

Null and alternative hypothesis

The hypothesis which is to be tested as called the null hypothesis.

The hypothesis which complements to the null hypothesis is called alternative hypothesis.

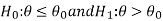

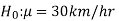

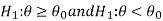

In the example of car, the claim is  and its complement is

and its complement is  .

.

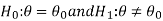

The null and alternative hypothesis can be formulated as-

And

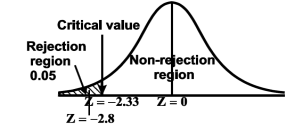

Critical region-

Let  be a random sample drawn from a population having unknown population parameter

be a random sample drawn from a population having unknown population parameter  .

.

The collection of all possible values of  is called sample space and a particular value represent a point in that space.

is called sample space and a particular value represent a point in that space.

In order to test a hypothesis, the entire sample space is partitioned into two disjoint sub-spaces, say,  and S –

and S –  . If calculated value of the teststatistic lies in, then we reject the null hypothesis and if it lies in

. If calculated value of the teststatistic lies in, then we reject the null hypothesis and if it lies in  then wedo not reject the null hypothesis. The region is called a “rejection region or critical region” and the region

then wedo not reject the null hypothesis. The region is called a “rejection region or critical region” and the region  is called a “non-rejection region”.

is called a “non-rejection region”.

Therefore, we can say that

“A region in the sample space in which if the calculated value of the test statistic lies, we reject the null hypothesis then it is called critical region or rejection region.”

The region of rejection is called critical region.

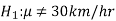

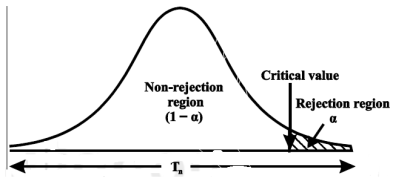

The critical region lies in one or two tails on the probability curve of sampling distribution of the test statistic it depends on the alternative hypothesis.

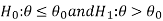

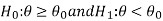

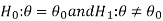

Therefore there are three cases-

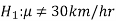

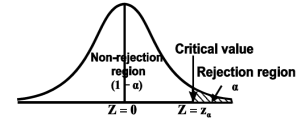

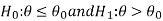

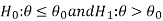

CASE-1: if the alternative hypothesis is right sided such as  then the entire critical region of size

then the entire critical region of size  lies on right tail of the probability curve.

lies on right tail of the probability curve.

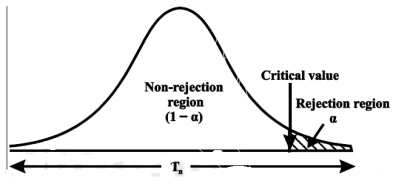

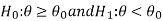

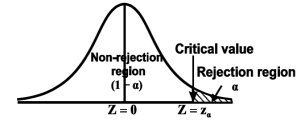

CASE-2: if the alternative hypothesis is left sided such as  then the entire critical region of size

then the entire critical region of size  lies on left tail of the probability curve.

lies on left tail of the probability curve.

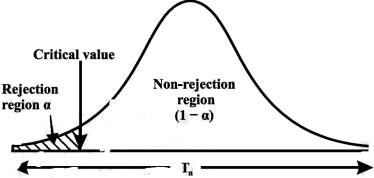

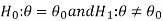

CASE-3: if the alternative hypothesis is two sided such as  then the entire critical region of size

then the entire critical region of size  lies on both tail of the probability curve

lies on both tail of the probability curve

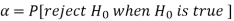

Type-1 and Type-2 error-

Type-1 error-

The decision relating to rejection of null hypo. When it is true is called type-1 error.

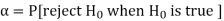

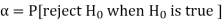

The probability of type-1 error is called size of the test, it is denoted by  and defined as-

and defined as-

Note-

is the probability of correct decision.

is the probability of correct decision.

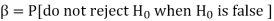

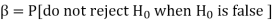

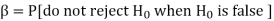

Type-2 error-

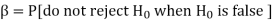

The decision relating to non-rejection of null hypo. When it is false is called type-1 error.

It is denoted by  and defined as-

and defined as-

Decision |  |  |

Reject  | Type-1 error | Correct decision |

Do not reject  | Correct decision | Type-2 error |

One tailed and two tailed tests-

A test of testing the null hypothesis is said to be two-tailed test if the alternative hypothesis is two-tailed whereas if the alternative hypothesis is one-tailed then a test of testing the null hypothesis is said to be one-tailed test.

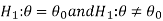

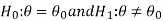

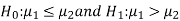

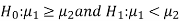

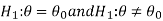

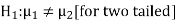

For example, if our null and alternative hypothesis are-

Then the test for testing the null hypothesis is two-tailed test because the

Alternative hypothesis is two-tailed.

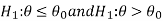

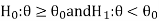

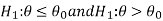

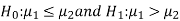

If the null and alternative hypotheses are-

Then the test for testing the null hypothesis is right-tailed test because the alternative hypothesis is right-tailed.

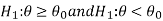

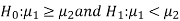

Similarly, if the null and alternative hypotheses are-

Then the test for testing the null hypothesis is left-tailed test because the alternative hypothesis is left-tailed

Procedure for testing a hypothesis-

Step-1: first we set up null hypothes is and alternative hypothesis

and alternative hypothesis  .

.

Step-2: after setting the null and alternative hypothesis, we establish a criteria for rejection or non-rejection of null hypothesis, that is, decide the level of significance ( ), at which we want to test our hypothesis. Generally, it is taken as 5% or 1% (α = 0.05 or 0.01).

), at which we want to test our hypothesis. Generally, it is taken as 5% or 1% (α = 0.05 or 0.01).

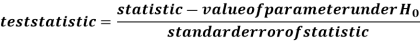

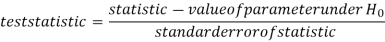

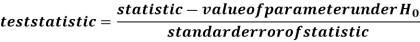

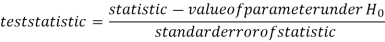

Step-3: The third step is to choose an appropriate test statistic under H0 for testing the null hypothesis as given below

Now after doing this, specify the sampling distribution of the test statistic preferably in the standard form like Z (standard normal),  , t, F orany other well-known in literature

, t, F orany other well-known in literature

Step-4: Calculate the value of the test statistic described in Step III on the basis of observed sample observations.

Step-5: Obtain the critical (or cut-off) value(s) in the sampling distribution of the test statistic and construct rejection (critical) region of size  .

.

Generally, critical values for various levels of significance are putted in the form of a table for various standard sampling distributions of test statistic such as Z-table,  -table, t-table, etc

-table, t-table, etc

Step-6: After that, compare the calculated value of test statistic obtained from Step IV, with the critical value(s) obtained in Step V andl ocates the position of the calculated test statistic, that is, it lies in rejection region or non-rejection region.

Step-7: in testing the hypothesis we have to reach at a conclusion, it is performed as below-

First- If calculated value of test statistic lies in rejection region at  level of significance then we reject null hypothesis. It meansthat the sample data provide us sufficient evidence against thenull hypothesis and there is a significant difference betweenhypothesized value and observed value of the parameter

level of significance then we reject null hypothesis. It meansthat the sample data provide us sufficient evidence against thenull hypothesis and there is a significant difference betweenhypothesized value and observed value of the parameter

Second- If calculated value of test statistic lies in non-rejection region at  level of significance then we do not reject null hypothesis. Its means that the sample data fails to provide us sufficient evidence against the null hypothesis and the difference between hypothesized value and observed value of the parameter due to fluctuation of sample

level of significance then we do not reject null hypothesis. Its means that the sample data fails to provide us sufficient evidence against the null hypothesis and the difference between hypothesized value and observed value of the parameter due to fluctuation of sample

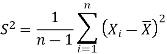

Procedure of testing of hypothesis for large samples-

The sample size more than 30 is considered as large sample size. So that for large samples, we follow the following procedure to test the hypothesis.

Step-1: first we set up the null and alternative hypothesis.

Step-2: After setting the null and alternative hypotheses, we have to choose level of significance. Generally, it is taken as 5% or 1% (α = 0.05 or0.01). And accordingly rejection and non-rejection regions will be decided.

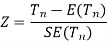

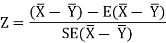

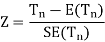

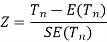

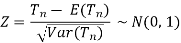

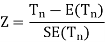

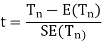

Step-3: Third step is to determine an appropriate test statistic, say, Z in case of large samples. Suppose Tn is the sample statistic such as sample mean, sample proportion, sample variance, etc. for the parameter  then for testing the null hypothesis, test statistic is given by

then for testing the null hypothesis, test statistic is given by

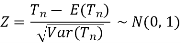

Step-4: the test statistic Z will assumed to be approximately normally distributed with mean 0 and variance 1 as

By putting the values in above formula, we calculate test statistic Z.

Suppose z be the calculated value of Z statistic

Step-5: After that, we obtain the critical (cut-off or tabulated) value(s) in the sampling distribution of the test statistic Z corresponding to  assumed in Step II.we construct rejection (critical) region of size α in the probability curve of the sampling distribution of test statistic Z.

assumed in Step II.we construct rejection (critical) region of size α in the probability curve of the sampling distribution of test statistic Z.

Step-6: Take the decision about the null hypothesis based on the calculated and critical values of test statistic obtained in Step IV and Step V.

Since critical value depends upon the nature of the test that it is one tailed test or two-tailed test so following cases arise-

Case-1 one-tailed test- when

(right-tailed test)

(right-tailed test)

In this case, the rejection (critical) region falls under the right tail of the probability curve of the sampling distribution of test statistic Z.

Suppose  is the critical value at

is the critical value at  level of significance so entireregion greater than or equal to

level of significance so entireregion greater than or equal to  is the rejection region and less than

is the rejection region and less than  is the non-rejection region

is the non-rejection region

If z (calculated value)≥  (tabulated value), that means the calculated value of test statistic Z lies in the rejection region, then we reject the null hypothesis H0 at

(tabulated value), that means the calculated value of test statistic Z lies in the rejection region, then we reject the null hypothesis H0 at  level of significance. Therefore, weconclude that sample data provides us sufficient evidence against thenull hypothesis and there is a significant difference between hypothesized or specified value and observed value of the parameter.

level of significance. Therefore, weconclude that sample data provides us sufficient evidence against thenull hypothesis and there is a significant difference between hypothesized or specified value and observed value of the parameter.

If z < that means the calculated value of test statistic Z lies in nonrejectionregion, then we do not reject the null hypothesis H0 at

that means the calculated value of test statistic Z lies in nonrejectionregion, then we do not reject the null hypothesis H0 at  level of significance. Therefore, we conclude that the sample data fails to provide us sufficient evidence against the null hypothesis and the difference between hypothesized value and observed value of the parameter due to fluctuation of sample.

level of significance. Therefore, we conclude that the sample data fails to provide us sufficient evidence against the null hypothesis and the difference between hypothesized value and observed value of the parameter due to fluctuation of sample.

So the population parameter

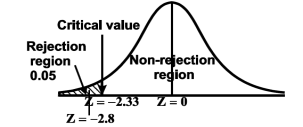

Case-2: when

(left-tailed test)

(left-tailed test)

The rejection (critical) region falls under the left tail of the probability curve of the sampling distribution of test statistic Z.

Suppose - is the critical value at

is the critical value at  level of significance then entireregion less than or equal to -

level of significance then entireregion less than or equal to - is the rejection region and greaterthan -

is the rejection region and greaterthan - is the non-rejection region

is the non-rejection region

If z ≤- , that means the calculated value of test statistic Z lies in therejection region, then we reject the null hypothesis H0 at

, that means the calculated value of test statistic Z lies in therejection region, then we reject the null hypothesis H0 at  level ofsignificance.

level ofsignificance.

If z >- , that means the calculated value of test statistic Z lies in thenon-rejection region, then we do not reject the null hypothesis H0 at

, that means the calculated value of test statistic Z lies in thenon-rejection region, then we do not reject the null hypothesis H0 at  level of significance.

level of significance.

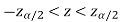

In case of two tailed test-

In this case, the rejection region falls under both tails of the probability curve of sampling distribution of the test statistic Z. Half the area (α) i.e.α/2 will lies under left tail and other half under the right tail. Suppose  and

and  are the two critical values at theleft-tailed and right-tailed respectively. Therefore, entire region lessthan or equal to

are the two critical values at theleft-tailed and right-tailed respectively. Therefore, entire region lessthan or equal to  and greater than or equal to

and greater than or equal to  are the rejection regions and between -

are the rejection regions and between - is the non-rejectionregion.

is the non-rejectionregion.

If Z that means the calculated value of teststatistic Z lies in the rejection region, then we reject the nullhypothesis H0 at

that means the calculated value of teststatistic Z lies in the rejection region, then we reject the nullhypothesis H0 at  level of significance.

level of significance.

If  that means the calculated value of test statistic Zlies in the non-rejection region, then we do not reject the nullhypothesis H0 at

that means the calculated value of test statistic Zlies in the non-rejection region, then we do not reject the nullhypothesis H0 at  level of significance.

level of significance.

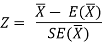

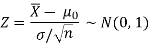

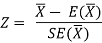

Testing of hypothesis for population mean using Z-Test

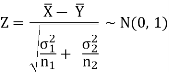

For testing the null hypothesis, the test statistic Z is given as-

The sampling distribution of the test statistics depends upon variance

So that there are two cases-

Case-1: when  is known -

is known -

The test statistic follows the normal distribution with mean 0 and variance unity when the sample size is the large as the population under study is normal or non-normal. If the sample size is small then test statistic Z follows the normal distribution only when population under study is normal. Thus,

Case-1: when  is unknown –

is unknown –

We estimate the value of  by using the value of sample variance

by using the value of sample variance

Then the test statistic becomes-

After that, we calculate the value of test statistic as may be the case ( isknown or unknown) and compare it with the critical valueat prefixed level of significance α.

isknown or unknown) and compare it with the critical valueat prefixed level of significance α.

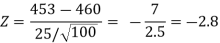

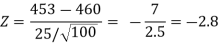

Example: A company of pens claims that a certain pen manufactured by him has a mean writing-life at least 460 A-4 size pages. A purchasing agent selects a sample of 100 pens and put them on the test. The mean writing-life of the sample found 453 A-4 size pages with standard deviation 25 A-4 size pages. Should the purchasing agent reject the manufacturer’s claim at 1% level of significance?

Sol.

It is given that-

Specified value of population mean =  = 460,

= 460,

Sample size = 100

Sample mean = 453

Sample standard deviation = S = 25

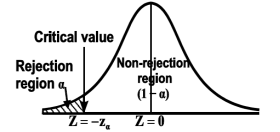

The null and alternative hypothesis will be-

H0 : μ ≥ μ0 = 460 and H1 : μ < 460

Also the alternative hypothesis left-tailed so that the test is left tailed test.

Here, we want to test the hypothesis regarding population mean when population SD is unknown. So we should used t-test for if writing-life of pen follows normal distribution. But it is not the case. Since sample size is n = 100(n > 30) large so we go for Z-test. The test statistic of Z-test is given by

We get the critical value of left tailed Z test at 1% level of significance is

Since calculated value of test statistic Z (= ‒2.8) is less than the critical value

(= −2.33), that means calculated value of test statistic Z lies in rejection region so we reject the null hypothesis. Since the null hypothesis is the claim so we reject the manufacturer’s claim at 1% level of significance.

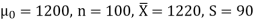

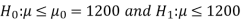

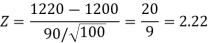

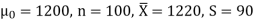

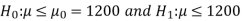

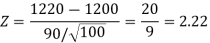

Example: A big company uses thousands of CFL lights every year. The brand that the company has been using in the past has average life of 1200 hours. A new brand is offered to the company at a price lower than they are paying for the old brand. Consequently, a sample of 100 CFL light of new brand is tested which yields an average life of 1220 hours with standard deviation 90 hours. Should the company accept the new brand at 5% level of significance?

Sol.

Here we have-

The company may accept the new CFL light when average life of

CFL light is greater than 1200 hours. So the company wants to test that the new brand CFL light has an average life greater than 1200 hours. So our claim is  > 1200 and its complement is

> 1200 and its complement is  ≤ 1200. Since complement contains the equality sign so we can take the complement as the null hypothesis and the claim as the alternative hypothesis. Thus,

≤ 1200. Since complement contains the equality sign so we can take the complement as the null hypothesis and the claim as the alternative hypothesis. Thus,

Since the alternative hypothesis is right-tailed so the test is right-tailed test.

Here, we want to test the hypothesis regarding population mean when population SD is unknown, so we should use t-test if the distribution of life of bulbs known to be normal. But it is not the case. Since the sample size is large (n > 30) so we can go for Z-test instead of t-test.

Therefore, test statistic is given by

The critical values for right-tailed test at 5% level of significance is

1.645

1.645

Since calculated value of test statistic Z (= 2.22) is greater than critical value (= 1.645), that means it lies in rejection region so we reject the null hypothesis and support the alternative hypothesis i.e. we support our claim at 5% level of significance

Thus, we conclude that sample does not provide us sufficient evidence against the claim so we may assume that the company accepts the new brand of bulbs

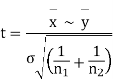

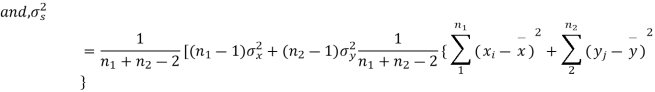

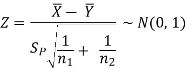

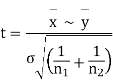

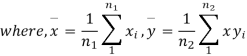

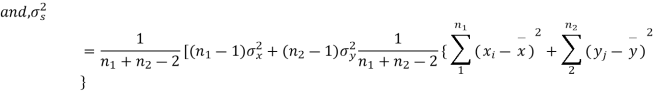

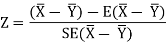

Significance test of difference between sample means

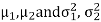

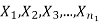

Given two independent examples  and

and  with means

with means  standard derivations

standard derivations  from a normal population with the same variance, we have to test the hypothesis that the population means

from a normal population with the same variance, we have to test the hypothesis that the population means  are same For this, we calculate

are same For this, we calculate

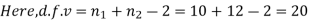

It can be shown that the variate t defined by (1) follows the t distribution with  degrees of freedom.

degrees of freedom.

If the calculated value  the difference between the sample means is said to be significant at 5% level of significance.

the difference between the sample means is said to be significant at 5% level of significance.

If  , the difference is said to be significant at 1% level of significance.

, the difference is said to be significant at 1% level of significance.

If  the data is said to be consistent with the hypothesis that

the data is said to be consistent with the hypothesis that  .

.

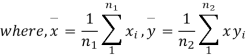

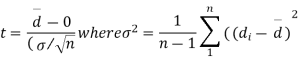

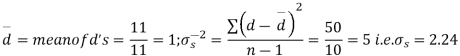

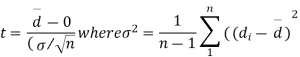

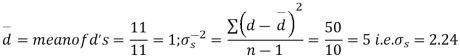

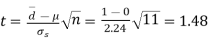

Cor. If the two samples are of same size and the data are paired, then t is defined by

=difference of the ith member of the sample

=difference of the ith member of the sample

d=mean of the differences = and the member of d.f.=n-1.

and the member of d.f.=n-1.

Example

Eleven students were given a test in statistics. They were given a month’s further tuition and the second test of equal difficulty was held at the end of this. Do the marks give evidence that the students have benefitted by extra coaching?

Boys | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

Marks I test | 23 | 20 | 19 | 21 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 23 | 16 | 19 |

Marks II test | 24 | 19 | 22 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 20 | 23 | 20 | 17 |

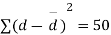

Sol. We compute the mean and the S.D. Of the difference between the marks of the two tests as under:

Assuming that the students have not been benefitted by extra coaching, it implies that the mean of the difference between the marks of the two tests is zero i.e.

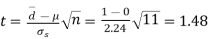

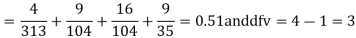

Then,  nearly and df v=11-1=10

nearly and df v=11-1=10

Students |  |  |  |  |  |

1 | 23 | 24 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

2 | 20 | 19 | -1 | -2 | 4 |

3 | 19 | 22 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

4 | 21 | 18 | -3 | -4 | 16 |

5 | 18 | 20 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

6 | 20 | 22 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

7 | 18 | 20 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

8 | 17 | 20 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

9 | 23 | 23 | - | -1 | 1 |

10 | 16 | 20 | 4 | 3 | 9 |

11 | 19 | 17 | -2 | -3 | 9 |

|

|

|  |

|  |

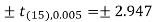

We find that  (for v=10) =2.228. As the calculated value of

(for v=10) =2.228. As the calculated value of  , the value of t is not significant at 5% level of significance i.e. the test provides no evidence that the students have benefitted by extra coaching.

, the value of t is not significant at 5% level of significance i.e. the test provides no evidence that the students have benefitted by extra coaching.

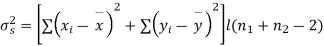

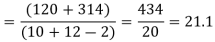

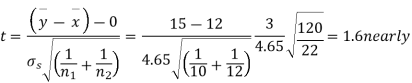

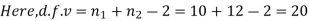

Example:

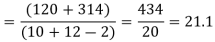

From a random sample of 10 pigs fed on diet A, the increase in weight in certain period were 10,6,16,17,13,12,8,14,15,9 lbs. For another random sample of 12 pigs fed on diet B, the increase in the same period were 7,13,22,15,12,14,18,8,21,23,10,17 lbs. Test whether diets A and B differ significantly as regards their effect on increases in weight?

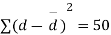

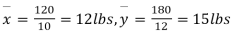

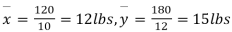

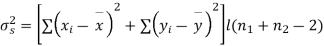

Sol. We calculate the means and standard derivations of the samples as follows

| Diet A |

|

| Diet B |

|

|  |  |  |  |  |

10 | -2 | 4 | 7 | -8 | 64 |

6 | -6 | 36 | 13 | -2 | 4 |

16 | 4 | 16 | 22 | 7 | 49 |

17 | 5 | 25 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

13 | 1 | 1 | 12 | -3 | 9 |

12 | 0 | 0 | 14 | -1 | 1 |

8 | -4 | 16 | 18 | 3 | 9 |

14 | 2 | 4 | 8 | -7 | 49 |

15 | 3 | 9 | 21 | 6 | 36 |

9 | -3 | 9 | 23 | 8 | 64 |

|

|

| 10 | -5 | 25 |

|

|

| 17 | 2 | 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

120 |

|

| 180 | 0 | 314 |

Assuming that the samples do not differ in weight so far as the two diets are concerned i.e.

For v=20, we find  =2.09

=2.09

The calculated value of

Hence the difference between the samples means is not significant i.e. thew two diets do not differ significantly as regards their effects on increase in weight.

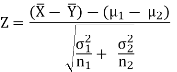

Testing of hypothesis for difference of two population means using Z-Test-

Let there be two populations, say, population-I and population-II under study.

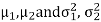

Also let  denote the means and variances of population-I andpopulation-II respectively where both

denote the means and variances of population-I andpopulation-II respectively where both  are unknown but

are unknown but  maybe known or unknown. We will consider all possible cases here. For testing thehypothesis about the difference of two population means, we draw a random sample of large size n1 from population-I and a random sample of large size n2from population-II. Let

maybe known or unknown. We will consider all possible cases here. For testing thehypothesis about the difference of two population means, we draw a random sample of large size n1 from population-I and a random sample of large size n2from population-II. Let  be the means of the samples selected frompopulation-I and II respectively.

be the means of the samples selected frompopulation-I and II respectively.

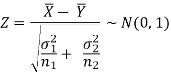

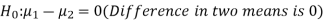

These two populations may or may not be normal but according to the central limit theorem, the sampling distribution of difference of two large sample means asymptotically normally distributed with mean  and variance

and variance

E  = E

= E  - E (

- E ( =

=

And

Var  = Var

= Var  + Var (

+ Var ( =

=

We know that the standard error =

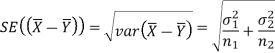

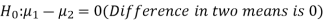

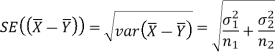

Here, we want to test the hypothesis about the difference of two population means so we can take the null hypothesis as

H0 :  (no difference in means)

(no difference in means)

Or

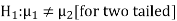

And the alternative hypothesis is-

Or

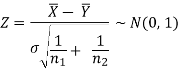

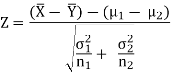

The test statistic Z is given by-

Or

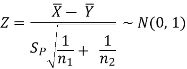

Since under null hypothesis we assume that  , therefore, we get-

, therefore, we get-

Now, the sampling distribution of the test statistic depends upon  that both are known or unknown. Therefore, four cases arise-

that both are known or unknown. Therefore, four cases arise-

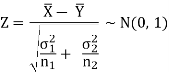

Case-1: When  are known and

are known and

In this case, the test statistic follows normal distribution with mean

0 and variance unity when the sample sizes are large as both the populations under study are normal or non-normal. But when sample sizes are small then test statistic Z follows normal distribution only when populations under study are normal, that is,

Case-2: When  are known and

are known and

In this case, the test statistic also follows the normal distribution as described in case I, that is,

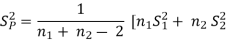

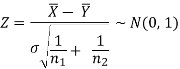

Case-3: When  are unknown and

are unknown and

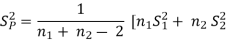

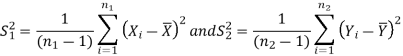

In this case, σ2 is estimated by value of pooled sample variance

Where,

And test statistic follows t-distribution with (n1 + n2 −2) degrees of freedom as the sample sizes are large or small provided populations under study follow normal distribution.

But when the populations are under study are not normal and sample sizes n1 and n2are large (> 30) then by central limit theorem, test statistic approximately normally distributed with mean

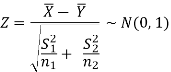

0 and variance unity, that is,

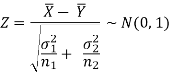

Case-4: When  are unknown and

are unknown and

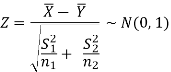

In this case,  are estimated by the values of the samplevariances

are estimated by the values of the samplevariances  respectively and the exact distribution of teststatistic is difficult to derive. But when sample sizes n1 and n2 arelarge (> 30) then central limit theorem, the test statisticapproximately normally distributed with mean 0 and variance unity,

respectively and the exact distribution of teststatistic is difficult to derive. But when sample sizes n1 and n2 arelarge (> 30) then central limit theorem, the test statisticapproximately normally distributed with mean 0 and variance unity,

That is,

After that, we calculate the value of test statistic and compare it with the critical value at prefixed level of significance α.

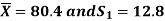

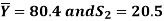

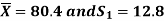

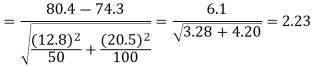

Example: A college conducts both face to face and distance mode classes for a particular course indented both to be identical. A sample of 50 students of face to face mode yields examination results mean and SD respectively as-

And other sample of 100 distance-mode students yields mean and SD of their examination results in the same course respectively as:

Are both educational methods statistically equal at 5% level?

Sol. Here we have-

n1 = 50  = 80.4 S1 = 12.8

= 80.4 S1 = 12.8

n2 = 100  = 74.3 S2 = 20.5

= 74.3 S2 = 20.5

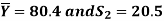

Here we wish to test that both educational methods are statistically equal. If  denote the average marks of face to face and distance mode students respectively then our claim is

denote the average marks of face to face and distance mode students respectively then our claim is  and its complement is

and its complement is  ≠

≠  . Since theclaim contains the equality sign so we can take the claim as the null hypothesisand complement as the alternative hypothesis. Thus,

. Since theclaim contains the equality sign so we can take the claim as the null hypothesisand complement as the alternative hypothesis. Thus,

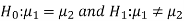

Since the alternative hypothesis is two-tailed so the test is two-tailed test.

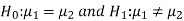

We want to test the null hypothesis regarding two population means when standard deviations of both populations are unknown. So we should go for t-test if population of difference is known to be normal. But it is not the case.

Since sample sizes are large (n1, and n2 > 30) so we go for Z-test.

For testing the null hypothesis, the test statistic Z is given by

The critical (tabulated) values for two-tailed test at 5% level of significance are-

± Zα/2 = ± Z0.025 = ± 1.96

Since calculated value of Z ( = 2.23) is greater than the critical values

(= ±1.96), that means it lies in rejection region so we

Reject the null hypothesis i.e. we reject the claim at 5% level of significance

Level of significance-

The probability of type-1 error is called level of significance of a test. It is also called the size of the test or size of the critical region. Denoted by  .

.

Basically it is prefixed as 5% or 1% level of significance.

If the calculated value of the test statistics lies in the critical region then we reject the null hypothesis.

The level of significance relates to the trueness of the conclusion. If null hypothesis do not reject at level 5% then a person will be sure “concluding about the null hypothesis” is true with 95% assurance but even it may false with 5% chance.

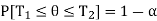

Confidence limits-

Let  be a random sample of size n drawn from a population having pdf (pmf)

be a random sample of size n drawn from a population having pdf (pmf)  .

.

Let  and

and  (here

(here  be two statistic such that the probability that the random interval [

be two statistic such that the probability that the random interval [ ] including the true value of population parameter

] including the true value of population parameter  , that is-

, that is-

Here  does not depends on

does not depends on  .

.

Then the random interval [ ] is called as (1 –

] is called as (1 –  100 % confidence interval for unknown population parameter

100 % confidence interval for unknown population parameter  and (1 –

and (1 –  is known as confidence coefficient.

is known as confidence coefficient.

The length of interval can be defined as-

Length = Upper confidence – Lower confidence limit

Key takeaways-

- Type-1 error-

The decision relating to rejection of null hypo. When it is true is called type-1 error.

The probability of type-1 error is called size of the test, it is denoted by  and defined as-

and defined as-

Note-

is the probability of correct decision.

is the probability of correct decision.

2. Type-2 error-

The decision relating to non-rejection of null hypo. When it is false is called type-1 error.

It is denoted by  and defined as-

and defined as-

3.

4.

5. For testing the null hypothesis, the test statistic Z is given as-

t distribution

General procedure of t-test for testing hypothesis-

Let X1, X2,…, Xn be a random sample of small size n (< 30)selected from a normal population, having parameter of interest, say,

Which is actually unknown but its hypothetical value-then

Step-1: First of all, we setup null and alternative hypotheses

Step-2: After setting the null and alternative hypotheses our next step is to decide a criteria for rejection or non-rejection of null hypothesis i.e. decide the level of significance  at which we want to test our nullhypothesis. We generally take

at which we want to test our nullhypothesis. We generally take = 5 % or 1%.

= 5 % or 1%.

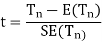

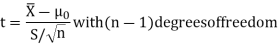

Step-3: The third step is to determine an appropriate test statistic, say, t for testing the null hypothesis. Suppose Tn is the sample statistic (may be sample mean, sample correlation coefficient, etc. depending upon  )for the parameter

)for the parameter  then test-statistic t is given by

then test-statistic t is given by

Step-4: As we know, t-test is based on t-distribution and t-distribution is described with the help of its degrees of freedom, therefore, test statistic t follows t-distribution with specified degrees of freedom as the case may be.

By putting the values of Tn, E(Tn) and SE(Tn) in above formula, we calculate the value of test statistic t. Let t-cal be the calculated value of test statistic t after putting these values.

Step-5: After that, we obtain the critical (cut-off or tabulated) value(s) in the sampling distribution of the test statistic t corresponding to assumedin Step II. The critical values for t-test are corresponding todifferent level of significance (α). After that, we construct rejection(critical) region of size

assumedin Step II. The critical values for t-test are corresponding todifferent level of significance (α). After that, we construct rejection(critical) region of size  in the probability curve of the samplingdistribution of test statistic t.

in the probability curve of the samplingdistribution of test statistic t.

Step-6: Take the decision about the null hypothesis based on calculated and critical value(s) of test statistic obtained in Step IV and Step V respectively.

Critical values depend upon the nature of test.

The following cases arises-

In case of one tailed test-

Case-1:  [Right-tailed test]

[Right-tailed test]

In this case, the rejection (critical) region falls under the right tail of the probability curve of the sampling distribution of test statistic t.

Suppose  is the critical value at

is the critical value at  level of significance then entireregion greater than or equal to

level of significance then entireregion greater than or equal to  is the rejection region and lessthan

is the rejection region and lessthan  is the non-rejection region.

is the non-rejection region.

If  ≥

≥ that means calculated value of test statistic t lies in therejection (critical) region, then we reject the null hypothesis

that means calculated value of test statistic t lies in therejection (critical) region, then we reject the null hypothesis  at

at  level of significance.

level of significance.

If  <

< that means calculated value of test statistic t lies in nonrejectionregion, then we do not reject the null hypothesis

that means calculated value of test statistic t lies in nonrejectionregion, then we do not reject the null hypothesis  at

at  level of significance.

level of significance.

Case-2:  [Left-tailed test]

[Left-tailed test]

In this case, the rejection (critical) region falls under the left tail of the probability curve of the sampling distribution of test statistic t.

Suppose - is the critical value at

is the critical value at  level of significance thenentire region less than or equal to -

level of significance thenentire region less than or equal to - is the rejection region andgreater than -

is the rejection region andgreater than - is the non-rejection region.

is the non-rejection region.

If ≤ −

≤ − that means calculated value of test statistic t lies in the rejection (critical) region, then we reject the null hypothesis

that means calculated value of test statistic t lies in the rejection (critical) region, then we reject the null hypothesis  at

at  level of significance.

level of significance.

If  >−

>− , that means calculated value of test statistic t lies in thenon-rejection region, then we do not reject the null hypothesis

, that means calculated value of test statistic t lies in thenon-rejection region, then we do not reject the null hypothesis  at

at  level of significance.

level of significance.

In case of two tailed test-

In this case, the rejection region falls under both tails of the probability curve of sampling distribution of the test statistic t. Half the area (α) i.e.α/2 will lies under left tail and other half under the right tail. Suppose - , and

, and  are the two critical values atthe left- tailed and right-tailed respectively. Therefore, entire region less than or equal to -

are the two critical values atthe left- tailed and right-tailed respectively. Therefore, entire region less than or equal to - and greater than or equal to

and greater than or equal to  arethe rejection regions and between -

arethe rejection regions and between - and

and  is the nonrejectionregion.

is the nonrejectionregion.

If  ≥

≥  or

or  ≤ -

≤ - , that means calculated value of teststatistic t lies in the rejection(critical) region, then we reject the nullhypothesis

, that means calculated value of teststatistic t lies in the rejection(critical) region, then we reject the nullhypothesis  at

at level of significance.

level of significance.

And if - <

< <

< , that means calculated value of teststatistic t lies in the non-rejection region, then we do not reject thenull hypothesis

, that means calculated value of teststatistic t lies in the non-rejection region, then we do not reject thenull hypothesis  at

at  level of significance.

level of significance.

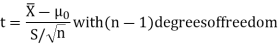

Testing of hypothesis for population mean using t-Test

There are the following assumptions of the t-test-

- Sample observations are random and independent.

- Population variance

is unknown

is unknown - The characteristic under study follows normal distribution.

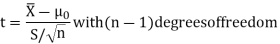

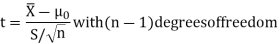

For testing the null hypothesis, the test statistic t is given by-

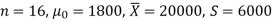

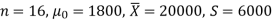

Example: A tube manufacturer claims that the average life of a particular category

Of his tube is 18000 km when used under normal driving conditions. A random sample of 16 tube was tested. The mean and SD of life of the tube in the sample were 20000 km and 6000 km respectively.

Assuming that the life of the tube is normally distributed, test the claim of the manufacturer at 1% level of significance using appropriate test.

Sol.

Here we have-

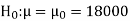

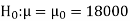

We want to test that manufacturer’s claim is true that the average life ( ) of tube is 18000 km. So claim is μ = 18000 and its complement is μ ≠ 18000. Since the claim contains the equality sign so we can take the claim as the null hypothesis and complement as the alternative hypothesis. Thus,

) of tube is 18000 km. So claim is μ = 18000 and its complement is μ ≠ 18000. Since the claim contains the equality sign so we can take the claim as the null hypothesis and complement as the alternative hypothesis. Thus,

Here, population SD is unknown and population under study is given to be normal.

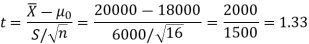

So here can use t-test-

For testing the null hypothesis, the test statistic t is given by-

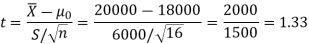

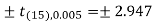

The critical value of test statistic t for two-tailed test corresponding(n-1) = 15 df at 1% level of significance are

Since calculated value of test statistic t (= 1.33) is less than the critical(tabulated) value (= 2.947) and greater that critical value (= − 2.947), that means calculated value of test statistic lies in non-rejection region, so we do not reject the null hypothesis. We conclude that sample fails to provide sufficient evidence against the claim so we may assume that manufacturer’s claim is true.

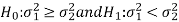

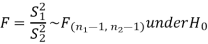

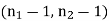

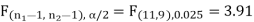

F-test-

Assumption of F-test-

The assumptions for F-test for testing the variances of two populations are:

- The samples must be normally distributed.

- The samples must be independent.

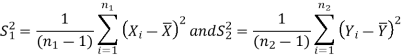

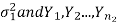

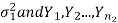

Let  be random sample of size

be random sample of size  taken froma normal population with

taken froma normal population with  and variance

and variance  be a random sample of size

be a random sample of size  from another normal population with mean

from another normal population with mean  and

and  .

.

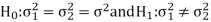

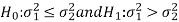

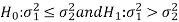

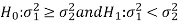

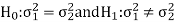

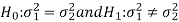

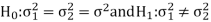

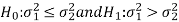

Here, we want to test the hypothesis about the two population variances so we can take our alternative null and hypotheses as-

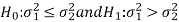

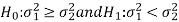

For two tailed test-

For one tailed test-

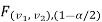

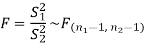

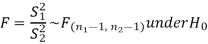

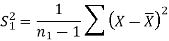

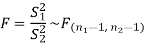

We use test statistic F for testing the null hypothesis-

And

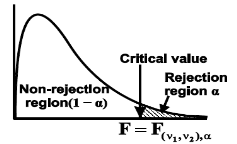

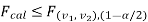

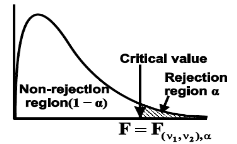

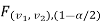

In case of one-tailed test-

Case-1:  (right-tailed test)

(right-tailed test)

In this case, the rejection (critical) region falls at the right side of the probability curve of the sampling distribution of test statistic F. Suppose  is the critical value of test statistic F with(

is the critical value of test statistic F with( =

=  – 1,

– 1,  =

=  – 1) df at

– 1) df at  level of significance so entire region greater than or equal

level of significance so entire region greater than or equal  tois the rejection (critical) region andless than

tois the rejection (critical) region andless than  is the non-rejection region.

is the non-rejection region.

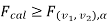

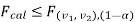

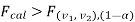

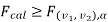

If  that means calculated value of test statistic lies inrejection (critical) region, then we reject the null hypothesis H0 at

that means calculated value of test statistic lies inrejection (critical) region, then we reject the null hypothesis H0 at level of significance. Therefore, we conclude that samples data provide us sufficient evidence against the null hypothesis and there isa significant difference between population variances

level of significance. Therefore, we conclude that samples data provide us sufficient evidence against the null hypothesis and there isa significant difference between population variances

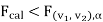

If  , that means calculated value of test statistic lies innon-rejection region, then we do not reject the null hypothesis H0 at

, that means calculated value of test statistic lies innon-rejection region, then we do not reject the null hypothesis H0 at  level of significance. Therefore, we conclude that the samples data fail to provide us sufficient evidence against the null hypothesis and the difference between population variances due to fluctuation of sample.

level of significance. Therefore, we conclude that the samples data fail to provide us sufficient evidence against the null hypothesis and the difference between population variances due to fluctuation of sample.

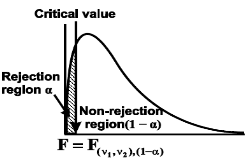

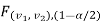

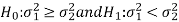

Case-2:  (left-tailed test)

(left-tailed test)

In this case, the rejection (critical) region falls at the left side of the probability curve of the sampling distribution of test statistic F. Suppose  is the critical value at

is the critical value at level of significance thenentire region less than or equal to

level of significance thenentire region less than or equal to  is the rejection(critical)region and greater than

is the rejection(critical)region and greater than  is the non-rejection region.

is the non-rejection region.

If  that means calculated value of test statistic lies inrejection (critical) region, then we reject the null hypothesis H0 at

that means calculated value of test statistic lies inrejection (critical) region, then we reject the null hypothesis H0 at  level of significance.

level of significance.

If  that means calculated value of test statistic lies innon-rejection region, then we do not reject the null hypothesis H0 at

that means calculated value of test statistic lies innon-rejection region, then we do not reject the null hypothesis H0 at  level of significance.

level of significance.

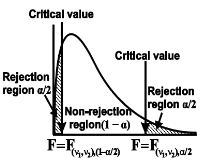

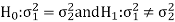

In case of two-tailed test-

When

In this case, the rejection (critical) region falls at both sides of the probability curve of the sampling distribution of test statistic F and half the area(α) i.e.α/2 of rejection (critical) region lies at left tail and other half on the right tail.

Suppose  and

and  are the two critical values at theleft-tailed and right-tailed respectively on pre-fixed

are the two critical values at theleft-tailed and right-tailed respectively on pre-fixed level ofsignificance. Therefore, entire region less than or equal to

level ofsignificance. Therefore, entire region less than or equal to  and greater than or equal to

and greater than or equal to  are the rejection (critical)regions and between

are the rejection (critical)regions and between  and

and  is the non-rejectionregion

is the non-rejectionregion

If  or

or  that means calculated value oftest statistic lies in rejection(critical) region, then we reject the nullhypothesis H0 at α level of significance.

that means calculated value oftest statistic lies in rejection(critical) region, then we reject the nullhypothesis H0 at α level of significance.

If  that means calculated value of teststatistic F lies in non-rejection region, then we do not reject the null hypothesis H0 at αlevel of significance.

that means calculated value of teststatistic F lies in non-rejection region, then we do not reject the null hypothesis H0 at αlevel of significance.

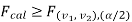

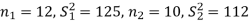

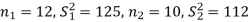

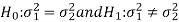

Example: Two sources of raw materials are under consideration by a bulb manufacturing company. Both sources seem to have similar characteristics but the company is not sure about their respective uniformity. A sample of 12 lots from source A yields a variance of 125 and a sample of 10 lots from source B yields a variance of 112. Is it likely that the variance of source A significantly differs to the variance of source B at significance level α = 0.01?

Sol.

The null and alternative hypothesis will be-

Since the alternative hypothesis is two-tailed so the test is two-tailed test.

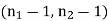

Here, we want to test the hypothesis about two population variances and sample sizes  = 12(< 30) and

= 12(< 30) and  = 10 (< 30) are small. Alsopopulations under study are normal and both samples are independent. So we can go for F-test for two population variances.

= 10 (< 30) are small. Alsopopulations under study are normal and both samples are independent. So we can go for F-test for two population variances.

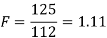

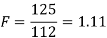

Test statistic is-

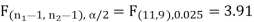

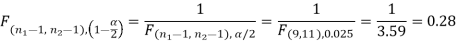

The critical (tabulated) value of test statistic F for two-tailed test corresponding  = (11, 9) df at 5% level of significance are

= (11, 9) df at 5% level of significance are  and

and

Since calculated value of test statistic (= 1.11) is less than the critical value (= 3.91) and greater than the critical value (= 0.28), that means calculated value of test statistic lies in non-rejection region, so we do not reject the null hypothesis and reject the alternative hypothesis. We conclude that samples provide us sufficient evidence against the claim so we may assume that the variances of source A and B is differ.

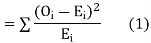

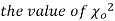

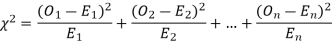

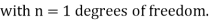

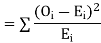

Chi-square distribution as a test of goodness of fit.

When a fair coin is tossed 80 times we expect from the theoretical considerations that heads will appear 40 times and tail 40 times. But this never happens in practice that is the results obtained in an experiment do not agree exactly with the theoretical results. The magnitude of discrepancy between observations and theory is given by the quantity  (pronounced as chi squares). If

(pronounced as chi squares). If  the observed and theoretical frequencies completely agree. As the value of

the observed and theoretical frequencies completely agree. As the value of  increases, the discrepancy between the observed and theoretical frequencies increases.

increases, the discrepancy between the observed and theoretical frequencies increases.

Definition.

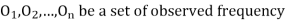

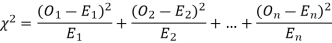

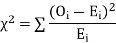

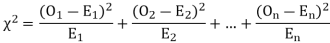

If  and

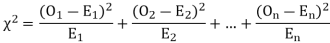

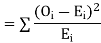

and  be the corresponding set of expected (theoretical) frequencies, then

be the corresponding set of expected (theoretical) frequencies, then  is defined by the relation

is defined by the relation

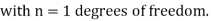

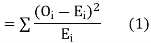

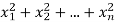

Chi – square distribution

If  be n independent normal variates with mean zero and s.d. Unity, then it can be shown that

be n independent normal variates with mean zero and s.d. Unity, then it can be shown that  is a random variate having

is a random variate having  distribution with ndf.

distribution with ndf.

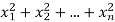

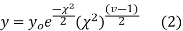

The equation of the  curve is

curve is

Properties of  distribution

distribution

- If v = 1, the

curve (2) reduces to

curve (2) reduces to  which is the exponential distribution.

which is the exponential distribution. - If

this curve is tangential to x – axis at the origin and is positively skewed as the mean is at v and mode at v-2.

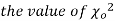

this curve is tangential to x – axis at the origin and is positively skewed as the mean is at v and mode at v-2. - The probability P that the value of

from a random sample will exceed

from a random sample will exceed  is given by

is given by

have been tabulated for various values of P and for values of v from 1 to 30. (Table V Appendix 2)

have been tabulated for various values of P and for values of v from 1 to 30. (Table V Appendix 2)

,the

,the curve approximates to the normal curve and we should refer to normal distribution tables for significant values of

curve approximates to the normal curve and we should refer to normal distribution tables for significant values of  .

.

IV. Since the equation of  curve does not involve any parameters of the population, this distribution does not dependent on the form of the population.

curve does not involve any parameters of the population, this distribution does not dependent on the form of the population.

V. Mean =  and variance =

and variance =

Goodness of fit

The values of  is used to test whether the deviations of the observed frequencies from the expected frequencies are significant or not. It is also used to test how will a set of observations fit given distribution

is used to test whether the deviations of the observed frequencies from the expected frequencies are significant or not. It is also used to test how will a set of observations fit given distribution  therefore provides a test of goodness of fit and may be used to examine the validity of some hypothesis about an observed frequency distribution. As a test of goodness of fit, it can be used to study the correspondence between the theory and fact.

therefore provides a test of goodness of fit and may be used to examine the validity of some hypothesis about an observed frequency distribution. As a test of goodness of fit, it can be used to study the correspondence between the theory and fact.

This is a nonparametric distribution free test since in this we make no assumptions about the distribution of the parent population.

Procedure to test significance and goodness of fit

(i) Set up a null hypothesis and calculate

(ii) Find the df and read the corresponding values of  at a prescribed significance level from table V.

at a prescribed significance level from table V.

(iii) From  table, we can also find the probability P corresponding to the calculated values of

table, we can also find the probability P corresponding to the calculated values of  for the given d.f.

for the given d.f.

(iv) If P<0.05, the observed value of  is significant at 5% level of significance

is significant at 5% level of significance

If P<0.01 the value is significant at 1% level.

If P>0.05, it is a good faith and the value is not significant.

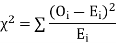

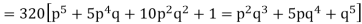

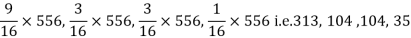

Example. A set of five similar coins is tossed 320 times and the result is

Number of heads | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Frequency | 6 | 27 | 72 | 112 | 71 | 32 |

Solution. For v = 5, we have

P, probability of getting a head=1/2;q, probability of getting a tail=1/2.

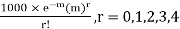

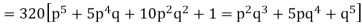

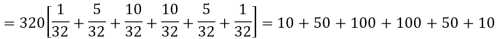

Hence the theoretical frequencies of getting 0,1,2,3,4,5 heads are the successive terms of the binomial expansion

Thus the theoretical frequencies are 10, 50, 100, 100, 50, 10.

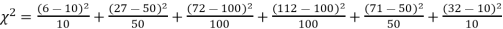

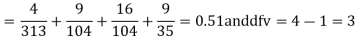

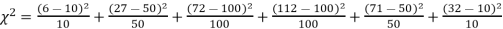

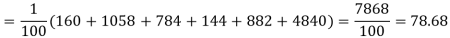

Hence,

Since the calculated value of  is much greater than

is much greater than  the hypothesis that the data follow the binomial law is rejected.

the hypothesis that the data follow the binomial law is rejected.

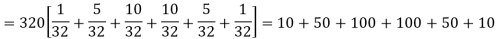

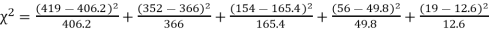

Example. Fit a Poisson distribution to the following data and test for its goodness of fit at level of significance 0.05.

x | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

f | 419 | 352 | 154 | 56 | 19 |

Solution. Mean m =

Hence, the theoretical frequency are

X | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total |

F | 404.9 (406.2) | 366 | 165.4 | 49.8 | 11..3 (12.6) | 997.4 |

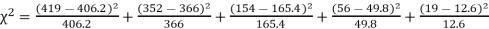

Hence,

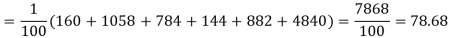

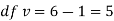

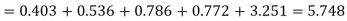

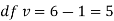

Since the mean of the theoretical distribution has been estimated from the given data and the totals have been made to agree, there are two constraints so that the number of degrees of freedom v = 5- 2=3

For v = 3, we have

Since the calculated value of  the agreement between the fact and theory is good and hence the Poisson distribution can be fitted to the data.

the agreement between the fact and theory is good and hence the Poisson distribution can be fitted to the data.

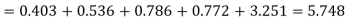

Example. In experiments of pea breeding, the following frequencies of seeds were obtained

Round and yellow | Wrinkled and yellow | Round and green | Wrinkled and green | Total |

316 | 101 | 108 | 32 | 556 |

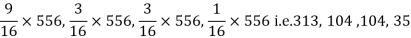

Theory predicts that the frequencies should be in proportions 9:3:3:1. Examine the correspondence between theory and experiment.

Solution. The corresponding frequencies are

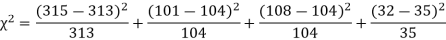

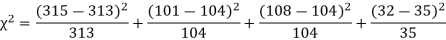

Hence,

For v = 3, we have

Since the calculated value of  is much less than

is much less than  there is a very high degree of agreement between theory and experiment.

there is a very high degree of agreement between theory and experiment.

Key takeaways-

- For testing the null hypothesis, the test statistic t is given by-

2.

References:

- E. Kreyszig, “Advanced Engineering Mathematics”, John Wiley & Sons, 2006.

- P. G. Hoel, S. C. Port And C. J. Stone, “Introduction To Probability Theory”, Universal Book Stall, 2003.

- S. Ross, “A First Course in Probability”, Pearson Education India, 2002.

- W. Feller, “An Introduction To Probability Theory and Its Applications”, Vol. 1, Wiley, 1968.

- N.P. Bali and M. Goyal, “A Text Book of Engineering Mathematics”, Laxmi Publications, 2010.

- B.S. Grewal, “Higher Engineering Mathematics”, Khanna Publishers, 2000.

Unit - 5

Stochastic process and sampling techniques

A stochastic process is a collection of random variables that take values in a set S, the state space.

The collection is indexed by another set T, the index set. The two most common index sets are the natural numbers T = {0, 1, 2, ...}, and the nonnegative real numbers

T = [0,∞), which usually represent discrete time and continuous time, respectively.

The first index set thus gives a sequence of random variables {X0,X1,X2, ...} andthe second, a collection of random variables {X(t), t ≥ 0}, one random variable for each time t. In general, the index set does not have to describe time but is also commonly used to describe spatial location. The state space can be finite, countably infinite, or uncountable, depending on the application.

In order to be able to analyze a stochastic process, we need to make assumptions on the dependence between the random variables. In this chapter, we will focus on the most common dependence structure, the so called Markov property, and in the next section we give a definition and several examples.

Stochastic process-

Stochastic process is a family of random variables {X(t )|t ∈T } defined on a common sample space S and indexed by the parameter t , which varies on an index set T .

The values assumed by the random variables X(t)are called states, and the set of all possible values from the state space of the process is denoted by I .

If the state space is discrete, the stochastic process is known as a chain.

A stochastic process consists of a sequence of experiments in which each experiment has a finite number of outcomes with given probabilities.

Probability vector-

Probability vector is a vector-

If  for every ‘i’ and

for every ‘i’ and

Stochastic matrices-

All the entries of square matrix P are non-negative and the sum of the entries of any row is one.

A vector v is said to be a fixed vector or a fixed point of a matrix A if vA= v and v = 0.

If v is a fixed vector of A, so is kv since

(kv)A = k(vA) = k(v) = kv.

Note-

- If v = (v1v2v3) is a probability vector of a stochastic matrix- P =

then vP is also a probability vector.

then vP is also a probability vector. - If P and Q are stochastic matrices then their product P Q is also stochastic matrix. Thus

is stochastic matrix for all positive integer values of n.

is stochastic matrix for all positive integer values of n. - The transition matrix P of a Markov chain is a stochastic matrix.

Example: Which vectors are probability vectors?

- (5/2, 0, 8/3, 1/6, 1/6)

- (3, 0, 2, 5, 3)

Sol.

- It is not a probability vector because the sum of the components do not add up to 1

- Dividing by 3 + 0 + 2 + 5 + 3 = 13, we get the probability vector

(3/13, 0, 2/13, 5/13, 3/13)

Example: show that  = (b a) is a fixed point of the stochastic matrix-

= (b a) is a fixed point of the stochastic matrix-

P =

Sol.

v P = (b a)

(b – ab + ab ba + a – ab) = (b a) = v

Example: Find the unique fixed probability vector t of

Sol.

Suppose t = (x, y, z) be the fixed probability vector.

By definition x + y + z = 1. Sot = (x, y,

1 −x −y), t is said to be fixed vector, if t P = t

On solving, we get-

Required fixed probability vector is-

Markov chain-

Let X0,X1,X2, ... Be a sequence of discrete random variables,t aking values in some set S and that are such that

P(Xn+1 = j | X0 = i0, . . . , Xn-1 = in-1, Xn = i) = P(Xn+1 = j|Xn = i)

For all i, j, i0, ..., in−1 in S and all n. The sequence {Xn} is then called a Markov chain

We often think of the index n as discrete time and say that Xni s the state of the chain at time n, where the state space S may be finite or countably infinite. The defining property is called the Markov property, which can be stated in words as “conditioned on the present, the future is independent of the past”. In general, the probability P(Xn+1 = j|Xn= i) depends on i, j, and n. It is, however, often the case (as in our roulette example) that there is no dependence on

n. We call such chains time-homogeneous and restrict our attention to these chains. Since the conditional probability in the definition thus depends only on I and j, we use the notation\

pij = P(Xn+1 = j | Xn = j), i, j ∈ S

And call these the transition probabilities of the Markov chain. Thus, if the chain is in state i, the probabilities pij describe how the chain chooses which state to jump to next. Obviously the transition probabilities have to satisfy the following two criteria:

(a) pij ≥ 0, for all I, j ∈ S, (b)

Classification of States:

The graphic representation of a Markov chain illustrates in which ways states can be reached from each other. In the roulette example, state 1 can, for example, reach state 2 in one step and state 3, in two steps. It can also reach state 3 in four steps, through the sequence 2, 1, 2, 3, and so on. One important property of state 1 is that it can reach any other state. Compare this to state 0 which cannot reach any other state. Whether or not states can reach each other in this way is of fundamental importance in the study of Markov chains, and we state the following definition.

Def: If pij(n) > 0 for some n, we say that state j is accessible from state i, written i→ j. If i→ j and j → i, we say that I and j communicate and write this i↔ j.

If j is accessible from i, this means that it is possible to reach j from I but not that this necessarily happens. In the roulette example, 1 → 2 since p12 >0, but if the chain starts in 1, it may jump directly to 0, and thus it will never be able to visit state 2. In this example, all nonzero states communicate with each other and 0 communicates only with itself.

In general, if we fix a state I in the state space of a Markov chain, we can find all states that communicate with I and form the communicating class containing i. It is easy to realize that not only does I communicate with all states in this class but they all communicate with each other. By convention, every state communicates with itself

(it can “reach itself in 0 steps”) so every state belongs to a class. If you wish to be more mathematical, the relation “↔” is an equivalence relation and thus divides the state space into equivalence classes that are precisely the communicating classes. In the roulette example, there are two classes

C0 = {0}, C1 = {1, 2, ...}

And in the genetics example, each state forms its own class and we thus have

C1 = {AA}, C2 = {Aa}, C3 = {aa}

In the ON/OFF system, there is only one class, the entire state space S. In this chain, all states communicate with each other, and it turns out that this is a desirable property.

Definition If all states in S communicate with each other, the Markov chain is said to be irreducible