Unit – 2

Theories of International Trade

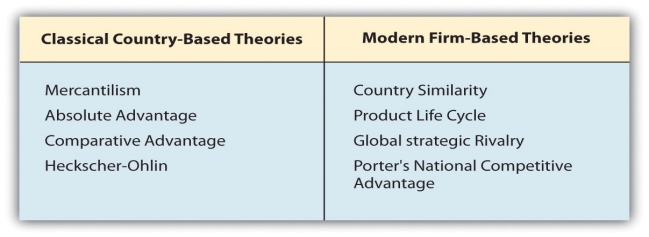

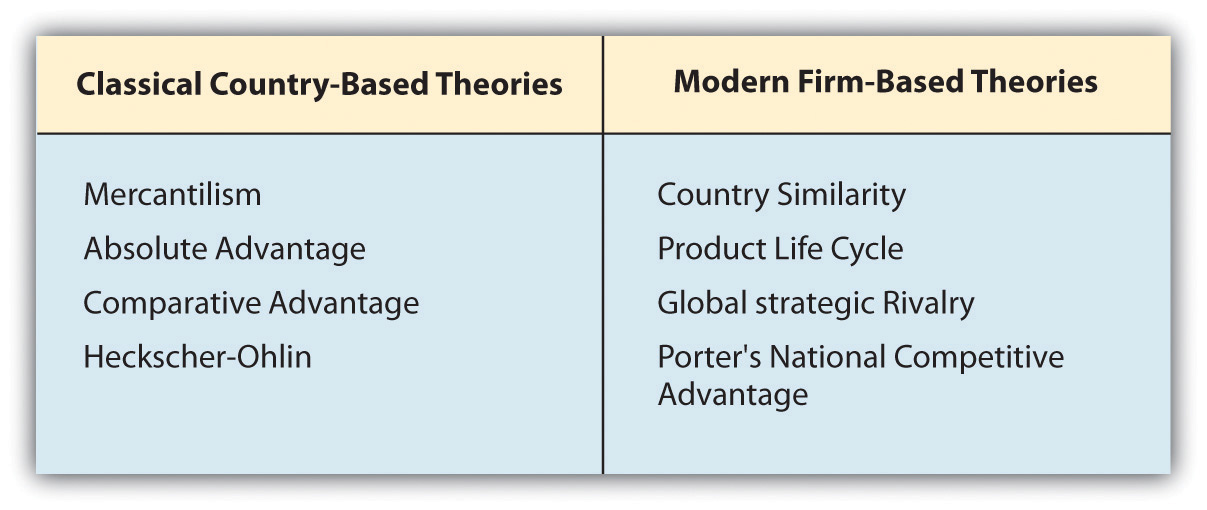

International trade theories are simply different theories to elucidate international trade. Trade is the concept of exchanging goods and services between two people or entities. International trade is then the concept of this exchange between people or entities in two different countries.

People or entities trade because they believe that they have the benefit of the exchange. they'll need or want the products or services. While at the surface, this many sound very simple, there's a good deal of theory, policy, and business strategy that constitutes international trade.

In this section, you’ll study the various trade theories that have evolved over the past century and which are most relevant today. Additionally, you’ll explore the factors that impact international trade and the way businesses and governments use these factors to their respective benefits to promote their interests.

Adam Smith is usually ignored as a trade theorist in text books of international economics due to the common belief that he only confirmed the rule of absolute advantages to explain the structure of foreign trade.

However, his vent-for-surplus approach is also interpreted as a pioneering study which stresses the importance of economies of scale in explaining the structure of trade.

Economists recognize the undeniable influence of Smith’s concepts like “extent of the market”, “division of labour”, “improved dexterity in every particular workman”, and “simple inventions coming from workman” on trade theory.

Adam Smith propounded the theory of absolute cost advantage because the basis of foreign trade; under such circumstances an exchange of goods will happen only if each of the 2 countries can produce one commodity at an absolutely lower production cost than the opposite country.

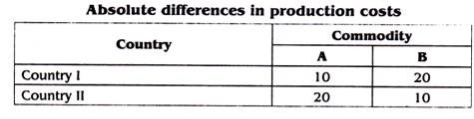

Suppose, there are two countries I & II and two commodities A and B. for instance , country can produce a unit of commodity (A) with 10 and a unit of commodity (B) with 20 labour units, which in country II, the production of a unit of (A) costs 20 and a unit of (15) 10 labour units. Now country I has absolute cost advantage in tin- production of (A) and it'll confine itself to the production of (A) and country II within the production of (B). precisely the same would happen if I and II were two regions of 1 country. We speak of an absolute- differences in costs because each country can produce one commodity at an absolutely lower cost them the opposite. Thus, in such a situation, a division of labor between them must result in an increase in total output.

Comparative cost advantage

David Ricardo agreed that absolute difference in cost gives a clear reason for trade to take place. He, however, went further to argue that even when a country has absolute advantage in the production of both commodities it is beneficial for that country to specialise in the production of that commodity in which it has a greater comparative advantage. The other country can be left to specialise in the production of that commodity in which it has less comparative advantage. According to Ricardo the essence for international trade is not the absolute difference in cost but comparative difference in cost. Ricardian theory is based on the following assumptions.

Assumptions-

On the basis of the above assumptions, David Ricardo explained his comparative cost difference theory, taking England and Portugal as two countries and wine and cloth as two countries.

country | 1 unit of wine | 1 unit of cloth |

England | 120L | 100L |

Portugal | 80L | 90L |

Portugal requires is less hours of labour for both wine and cloth. One unit of wine in Portugal is produced with the help of 80 labour hours as against 120 labour hours required in England. From this it could be argued that there is no need for trade as Portugal produces both commodities at a lower cost. Ricardo however, tried to prove that Portugal stands to gain by specializing in the commodities in which it has a greater comparative advantage. Comparative cost advantage of Portugal can be expressed in terms of cost ratio.

Cost ratios of producing wine and cloth can be expressed as:

Portugal | England | ||

wine | cloth | wine | cloth |

< | > | ||

0.66 < 0.9 | 1.5 > 1.11 | ||

Portugal has advantage of lower cost of production both in wine and cloth. However the difference in cost, that is the comparative advantage is greater in the production of wine (1.5-0.66=0.84) than in cloth (1.11-0.9-0.21).

Even in terms of absolute number of days of labour Portugal has a larger comparative advantage in wine, that is, 40 labourers less than England as compared to cloth where the difference is only 10, (40>10). Accordingly Portugal specializes in the production of cloth where its comparative disadvantage is lesser than in wine.

Comparative Cost Benefits Both: Let us explain Ricardian contention that comparative cost benefits both the participants, though one of them had clear cost advantage in both commodities. To prove its, let us work out the internal exchange ratio.

country | wine | cloth | domestic exchange rate | international exchange rate |

| W : C | W : C | ||

England Portugal | 120 80 | 100 90 | 1 : 1.2 1 : 0.89 | 1 : 1 1 : 1 |

Let us assume these two countries enter into trade at an international exchange rate (Terms of Trade) 1:1.

At this rate, England specializing in cloth and exporting one unit of cloth gets in turn one unit of wine. At home it is required to give 1.2 units of cloth for unit of wine. England thus gains 0.2 of cloth i.e. wine is cheaper from Portugal by 0.2 unit of cloth.

Similarly Portugal gets one unit of cloth from England for its one unit of wine as against 0.89 of cloth at home thus gaining extra cloth of 0.11. Here both England and Portugal gain from the trade i.e. England gives 0.2 less of cloth to get one unit of wine and Portugal gets 0.11 more of cloth for one unit of wine.

In this example, Portugal specializes in wine where it has greater comparative advantage leaving cloth at home for England in which it has less comparative disadvantage. The example also validates Ricardian Argument that the base for international trade is the comparative difference in cost and not the absolute difference in cost.

Introduction:

The drawbacks of the classical theory of international trade induced the Swedish economist Prof. Heckscher (1919) to develop an alternate explanation of comparative advantage theory. His theory was further improved by his pupil BertilOhlin(1933). Hence it is known as Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O)theory.

Hecksher-Ohlin (H-O) theory argues that there is no need for a separate theory to explain international trade. According to it, international trade is but a special case of interregional trade. Factor immobility which was the base for a separate explanation of international trade by classical economists does not hold true as factors are mobile or immobile even between two regions of the same country and also between the two countries. It is difference in degree rather than in nature.

The Modern or Hecksher-Ohlin (H-O) Theory explains the new approach to comparative advantage on the basis of general value theory. From all the forces that work together in general equilibrium, H-O theory isolates the differences in physical availability or supply of factors of production among the nations to explain the difference in relative commodity prices and trade between the countries. According to this theory “a nation will export the commodity whose production requires the intensive use of the nation’s relatively abundant and cheap factor and import the commodity whose production requires the intensive use of the nation’s relatively scarce and expensive factor”.

H-O theory explains the modern approach to international theory on the basis of the following assumptions:

There are two countries, each having two factors ( Labour and capital ) and producing two commodities.

There is perfect competitions in both commodity and factor markets.

All production functions are homogeneous of the first degree i.e. production is subject to constant returns to scale.

Factors are mobile within the country and immobile between countries. In international trade commodities move between the countries instead of factors.

The two countries differ in factor supply.

Each commodity differs in factor intensity.

Factor intensity differ between the commodities but are same in both countries for each commodity i.e. if goods X is labour intensive, it will be so in both countries. However goods X and Y differ in factor intensity in the same country.

Full employment of factor exists in both economies.

Trade is free i.e. there are no trade restrictions in the form of tariffs or non-tariff barriers.

No transport cost.

On the basis of the above assumptions it can be stated that (i) each commodity differ in factor intensity (ii) each country differs in factor endowments leading to differences in factor prices. It is therefore necessary to understand the above terms factors intensity and factor abundance in order to explain H-O theory.

(A) Factor Intensity

In our two country commodity model, commodity Y is capital intensive if the capital-labour ratio (K/L) in the production of Y is greater than K/L used in the proportion of X. To explain with an example, if commodity Y requires 2 units of capital (2K) and 2 units of labour (2L), the capital-labour ratio (K/L) for producing commodity Y is 2/2 = 1. For commodity X, if the required inputs are 1K and 4L, the capital-labour (K/L) ratio ¼.

The ratios can be stated as :

For commodity Y, the K/L = 2K /2L = 1

For commodity X, the K/L = 1K/4L =1/4

Here commodity Y is capital intensive and X is labour intensive

Commodity | Capital | Labour | K/L Ratio |

Y X | 2 3 | 2 12 | 1 1/4 |

Capital or labour intensity is not measured in absolute terms but by the ratio i.e. units of capital per labour or units of labour per capital. In our example, K/L ratio for Y is 1 and for X is ¼.

Instead, if units of capital and labour used in the production of Y are 2K and 2L where as for X, 3K and 12L, commodity Y still remains capital intensive through X requires more capital in absolute terms i.e. 3K. Capital used per labour in the production of X is 3K/2L i.e. 3/12 = ¼. Where as for Y it is 2K/2L = 1 as shown in table

Commodity | Capital | Labour | K/L Ratio |

Y X | 2 3 | 2 12 | 1 1/4 |

Factor intensity, therefore is measured by the factor ratios and not by absolute units.

In our example of two commodities, two factors and two countries, we say commodity Y is capital intensive if capital-labour ratio (K/L) of Y is greater than the K/L ratio of X. to illustrate the point let us say that production of one unit of Y requires two units of capital (2K) and 2 unit labour (2L).the capital-labour ratio (K/L) of Y is2/2 =1. Similarly, if the production of X requires 3K and 12L, the capital-labour ratio of X is ¼. Here we say Y is capital intensive and X is labour intensive.

It is to be noted that goods are not categorized based on absolute quantity or units of capital and labour used in the production of a unit of good Y or X but the ratio of capital-labour of each c6K and 24L, here good X requires more capital in absolute number than Y. Yet in terms of ratio, it is Y which is capital intensive (5/5 =1) whereas X is labour intensive (6/24 = ¼).

(B) Factor Abundance

Factor Abundance in Physical Terms

Nations differ in factor endowments. Some have more natural resources, some have more of labour and others more of capital. A given county’s factor abundance can be defined either in physical terms or in terms of relative factor prices. In our two country model, country I is capital abundant, if in physical terms the ratio of total amount of capital (TK) to the total amount of labour (TL) that is (TK/TL) in nation 1 is greater than nation 2 i.e. > . It should be noted that it is not the absolute amount of capital and labour but the ratio of the total amount of capital to the total amount of labour. Country 1 may have a lesser quantity of capital than country 2, yet country 1 will be capital abundant if TK to TL in country 1 is greater than in country 2.

Factor abundance in physical terms can also be explained with the help of production possibility curve OR production frontier, as shown in fig.

In the diagram below, country I is capital abundant, therefore, its production possibility curve is skewed towards Y-axis. Country II is labour abundant, accordingly its production possibility curve is skewed towards X-axis.

Commodity Y is capital intensive.

Commodity X is labour intensive.

Country I can produce OA of Y i.e. CA quantity more than country II. Similarly country II can produce OD of X, i.e. BD quantity more than country I. country II can produce more of X which is labour intensive because it is capital intensive due to its abundant capital.

The domestic price lines are PP1 and PP2 in countries I and II. The points E and Q are the respective equilibrium points of production and consumption. The price lines P1 and P2 indicate that commodity Y is cheaper in country I and X in country II, providing the basis for trade.

Factor Abundance in Terms of Factor Price

The cause of international trade is the difference in commodity prices. Price of commodity differs because of cost of production which in turn depends on factor prices. It is therefore necessary to explain factor abundance theory in terms of factor prices.

A nation is capital abundant if the ratio of the capital price to the labour price (PK/PL) is lower in it than in the other.

It can be stated as: The two definitions give us the same meaning. The physical abundance explains the supply side. The price ratios are based on the price of factors determined by the demand for and supply of factors. The demand for factors derived demand i.e. derived from the demand for commodities produced with the help of factors. In our two nations model, demand is assumed to be the same in both the nations. In a country where the supply of physical units of capital (K) is more, its price has to be lower in comparison to the other factor(L). If in nation 1, the price of capital i.e. interest (r) is less than the price of labour i.e. wage (w) and in nation 2, r is more than w, then we have . Here nation 1 is a capital abundant country.

From our above analysis we can derive the following conclusions:

Each country differs in factors endowments, some have abundant labour, some possess plenty of land and others have huge amount of capital and so on.

Each country specializes in the production of that commodity which requires more of its abundant factor.

Abundance of a factor makes it cheaper in terms of its price.

Low factor prices result in low cost of production and in turn low commodity prices.

Low commodity price is the basis of international trade.

1. Introduction to the Leontief Paradox.

2. Loentief Paradox and Evidence associated with Other Countries.

3. Reconciliation.

4. Criticisms.

Introduction to the Leontief Paradox:

The Heckscher-Ohlin theorem gave a generalisation that the capital-abundant counties tend to export capital-intensive goods while labour- abundant countries tend to export the labour- intensive goods. W.W. Leontief put this generalisation to empirical test in 1953 and located the results that were contrary – to the generalisation provided by the H-O theory.

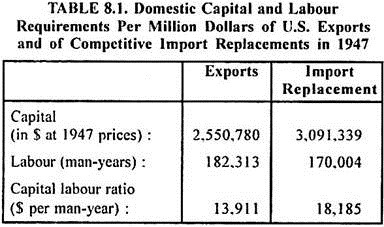

Leontief made use of 1947 input-output tables associated with the U.S. economy. 200 groups of industries were consolidated into 50 sectors, of which 38 traded their products directly on the international market. He took only two factors of production— labour and capital. His main empirical results are stated in Table. 8.1.

Table 8.1, shows that import replacement industries in the U.S. had been employing 30 percent more of capital than the export industries. The capital-labour ratio was higher in the import- replacement industries than the export industries. It suggested that the exports of U.S, generally recognised because the capital-abundant country, were labour-intensive.

Leontief therefore, concluded, “American participation in the international division of labour is predicated on its specialisation in labour intensive instead of capital-intensive lines of production. In other words, this country resorts to foreign trade order to economize its capital and eliminate its surplus labour instead of vice-versa.”

In brief, capital-abundant countries export labour- intensive goods and labour-abundant countries export capital-intensive goods. This reflects what's called as ‘Leontief Paradox’ as this conclusion goes against H-O theory. Although the us may be a capital-abundant country, yet its specialisation is found in the labour-intensive commodities.

The conclusion derived by Leontief not only surprised himself but startled the academicians throughout the planet. The economists undertook intense research for re-examining both the H-O theory and Leontief paradox. The attempts were also made on empirical grounds to reconcile the Leontief analysis with the H-O theory. Several economists investigated the causes of bias in Leontief’s work and exposed the methodological and statistical weaknesses and inaccuracies in his analysis.

Loentief Paradox and Evidence associated with Other Countries:

The Loentief paradox brought into focus the crucial issue of the validity or otherwise of H-O theory. Many economists conducted Loentief type studies associated with other countries. The evidence is, however, not conclusive a method or the opposite. While a number of the empirical studies put an issue mark on the validity of H-O theory, the others have gone in favour of it.

A study attempted by Tatemato and Ichimura concerning Japan has confirmed the Leontief paradox. Japan albeit a labour-abundant country, imported labour-intensive goods like raw materials and exported capital-intensive goods like automobiles, computers, T.V. sets, watches etc.

According to these writers, this pattern of trade isn't according to the H-O theory. They attributed such a trade pattern to the fact that nearly 75 percent of Japan’s exports were directed to the Third World countries which were more capital- scarce that Japan. From their viewpoint, Japanese exports to them were capital-intensive. In contrast to the US, Japan was labour-abundant and capital-scarce. Consequently her exports to the advanced countries just like the United States had a lower capital-labour ratio. in this way, their findings confirmed the validity of H-O theory.

The H-O theory found support from a study made by W. Stopler and K. Roskamp concerning the erstwhile East Germany in 1956. Almost 75 percent of her trade was with the countries of the communist bloc. East Germany was relatively more capital-abundant than the latter. At the same time, her exports to those countries were relatively capital- intensive and imports labour-intensive.

D.F. Wahl conducted a study associated with the trade pattern of Canada in 1961. This study showed that Canadian exports to the U.S.A, the main trading partner of Canada, were relatively more capital- intensive than her imports. It lent support to the Leontief paradox and contradicted the H-O theory.

Another study that provided support to the Leontief paradox was made by R. Bhardwaj in 1961 concerning India’s trade pattern. He showed that Indian exports, generally, were more labour- intensive, while imports were capital-intensive. However, in her trade with the US, the exports were capital-intensive and imports were labour-intensive.

Thus, even this study ran counter to the H-O theory. There can be certain reasons for greater capital-intensity of exports by India and a few other LDC’s to the us . Firstly, these countries depend greatly on the technology imported from the advanced countries, as they do not themselves have an indigenous technology suited to their own factor endowments. The imported technology is very capital-intensive.

As a result, the exported goods have a relatively high capital- labour ratio. Secondly, India relied heavily on the imports of food grains and many other consumer products from the united states until 1970’s. That accounted for high labour-intensity of her imports from the us . Thirdly, there's a considerable direct foreign investment by MNC’s owned by the us and the European countries in India and other LDC’s.

They generally operate in the export sector and produce goods through highly capital-intensive techniques. Which will be one among the reasons for high capital-intensity of their exports, even though they're capital-scarce Fourthly, there's factor price distortion in the LDC’s, i.e., the factor prices existing in these countries don't necessarily reflect their factor proportions.

There is the likelihood that labour is over-priced and capital is underpriced in the LDC’s on account of such factors as strong trade union pressures, minimum wage laws, capital consumption allowances and other subsidies on capital and duty free imports of technology and capital goods from abroad. because the over-pricing of labour and underpricing of capital cause factor-price distortion, there's likelihood that the labour-surplus and capital-scarce countries like India export capital-intensive goods and import labour-intensive goods.

The Leontief paradox was supported by the study made by M. Diab in 1956 concerning the us trade with Canada, Britain, Netherlands, France and Norway. This study, counting on Colin Clark’s data, demonstrated that the us was having a coffee capital-labour ratio in her exports than the above-mentioned countries.

L.Tarshis approached the whole problem indirectly by comparing the internal commodity prices in several countries. The study revealed that the worth ratio of capital-intensive relative to labour- intensive goods was lower within the united states and higher in other countries. Since the united states is a relatively capital-abundant country, the result's fully according to Heckscher-Ohlin theory.

In the empirical studies made by E.E. Leamer in 1980 and 1984, it's suggested that the comparison of K-L ratio within the multi-factor world should be in production versus consumption rather than in exports versus imports. Applying this approach to 1947 Leontief’s data, Learner concluded that K-L ratio was indeed greater in the United States production than the united states consumption. That strengthened the H-O theory and refuted Leontief paradox. The study made by Stern and Maskus in 1981 for the year 1972 confirmed the H- O theory even when natural resources industries were excluded.

In a 1987 study Bowen, Learner and Sveikauskas, employed more complete 1967 cross- sectional data on trade, factor input requirements and factor endowments of 27 countries, 12 factors (resources) and several commodities. They concluded that H-O trade theory was valid in about fifty percent cases.

It is now sufficiently clear that the empirical studies concerning the Leontief paradox or H-O theory, have provided conflicting conclusions. Until convincing or more conclusive evidence becomes available in support of Leontief paradox, the H-O theory must be deemed as valid.

Reconciliation between Leontief Paradox and Heckscher-Ohlin Theory:

Although the conclusion given by Leontief was in contradiction to the generalisation given by H-O theory, yet Leontief never attempted to supplant the factor proportions theory. He rather tried to explain the reasons thanks to which he received a result different from that provided by the H-O theory. Many other economists too attempted to reconcile the Leontief paradox with the H-O theory of international trade.

The more prominent explanations during this context are as follows:

(i) Labour Productivity:

Leontief himself tried to cause reconciliation between his paradox and H-O theory through the argument that the us , though a labour-scarce country in strictly quantitative or conventional terms, is really a labour-abundant country. The productivity of labour in the United States is about 3 times that of labour in the foreign countries. The higher productivity of the American labour was attributed by him to raised organization and entrepreneurship in the united states than in other countries.

In view of this, it's not surprising that the labour- abundant us exports those products, which have relatively greater labour-intensity. There’s no doubt that the productivity of labour is higher in the united states than in other countries. But the multiple of three, as assumed by Leontief was clearly arbitrary. During a study conducted by Kreinin in 1965, it had been revealed that the productivity of American labour was over that of the foreign labour only by 20 to 25 percent and not by 300 percent.

Given such a situation, the us can't be regarded as a labour-abundant country. Salvatore pointed out that the higher labour productivity in the us than in other countries implies a better productivity of capital also therein country relative to the opposite countries. So both U.S. labour and capital should be multiplied by an equivalent multiple 3. But which will leave the relative capital-abundance of the us as unaffected. Leontief himself afterward withdrew this explanation.

(ii) Human Capital:

Leontief had found greater capital-intensity in the U.S. import- substitution industries than in export industries because he didn't include the investment in human capital. He had emphasized only upon the physical capital like machinery, equipment, buildings etc. The investment in human capital means spending on education, skill creation and health.

Such an investment brings about substantial increase in the productivity of labour. There’s little doubt that the United States is most well-endowed with human capital. If the human capital component is added to the physical capital, the U.S. exports become much more capital-intensive relative to her import- substitutes. It’s confirmed by the empirical studies conducted by Kravis (1956), Kenen (1965) and Keesing (1966).

(iii) Natural Resources:

In Leontief s analysis, the part played by natural resources in determining the composition of trade of a country had been over-looked. A prominent study made by J. Vanek showed that the United States was relatively scarce of several natural resources. There’s complementarity between capital and natural resources in the field of production. The efficient utilization of capital requires large amounts of natural resources also. The us imports, in fact, are the natural resources intensive products like minerals and forest products.

These products have high capital- labour ratio in the United States process of production. By importing such products, the us actually conserves her scarce natural resources. At a similar time, she exports the farm products that have low capital-labour ratio. the precise assessment of the validity of H-O theory or Leontief paradox are often possible only after the quantification of the contribution of natural resources during a precise manner, gets materialised.

(iv) Factor-Intensity Reversal:

The H-O theorem doesn't recognize the reversal of factor intensity. It assumes that a commodity cloth is labour-intensive both in the U.S.A. and India and another commodity steel is capital-intensive in both these countries. The factor-intensity reversal can occur if the united states produces and exports textiles through capital-intensive techniques but India produces and exports a similar commodity though labour-intensive techniques.

In such a situation, the H-O theory can't be sustained and Leontief paradox may become applicable in one among the 2 countries. But the factor-intensity reversal must be widespread or substantial to repudiate the H-O theory. A widely discussed study by Minhas recognised the validity of factor-intensity reversal but the studies made by Leontief himself in 1964 and Moroney found it to be quantitatively insignificant. It’s found insufficient to reject strong factor intensity hypothesis of the H-O theory or justify Leontief’s paradox.

(v) Consumption Pattern:

Another explanation to reconcile the H-O theory and Leontief paradox is in terms of the consumption pattern in the U.S. economy. it's sometimes argued that the American consumption pattern was so strongly biased in favour of capital-intensive goods that the prices of such commodities were relatively higher in the united states and, therefore, she would export relatively labour-intensive goods.

This argument tends to support Leontief paradox. A 1957 study concluded by Houthakker about the consumption patterns in many counties showed that the income elasticity of demand for food, clothing, housing and several other goods was strikingly similar across nation. Consequently, the reason of Leontief paradox in terms of taste differences can't be accepted.

(vi) International Demand Pressures:

The high labour-intensity in the united states exports and capital-intensity just in case of import-replacement products are often attributed to the demand pressures in the united states and her trading partners. Romney Robinson explained Leontief paradox without repudiating the Heckscher-Ohlin theory on the idea of relative patterns of demand existing in the united states and other countries.

According to him, the pattern of demand in the us is such it's compelled to import all such commodities that have a comparatively higher capital-intensity. Similarly, the pressure of demand in foreign countries is such the United States is required to export the labour-intensive commodities.

(vii) Research and Development:

Leontief received a conclusion which is in contradiction to the H-O theory also because he over-looked the effect of research and development expenditure on the trade pattern. the worth of output derived from a given stock of materials and human resources increases on account of research and development activity. Even casual observation demonstrates that the U.S. exports are research and development sensitive.

The study attempted by W. Gruber, D. Mehta and R. Vernon found that the U.S. export performance is closely associated with the investment in research and development. it's true that this test is indirect, because technology differences haven't thus far been recognised because the basis for trade, but still the relative comparative advantages of various countries could also be influenced by the research and development expenditure.

(viii) Tariff Structure:

Leontief paradox is often reconciled with H-O theory, if it's recognised that the tariff structure existing between the trading countries can influence the pattern of trade. A tariff is a tax on imports and it tends to restrict imports. A 1954 study made by Kravis showed that the labour-intensive industries were most heavily protected in the United States. That perhaps reduced the labour-intensity of U.S. import substitutes. Similarly the LDC’s could also be compelled to allow duty-free import of agricultural products or other labour-intensive products from the US so as to tide over their domestic shortages.

Criticisms of Leontief Paradox:

The main objections against it are as follows:

(i) Inherent Bias:

(ii) Inclusion of Industries with Low Capital-Intensity:

(iii) Incompatibility of Input-Output Model:

(iv) Problem of Aggregation:

(v) Irrelevant Factor-Intensity Comparison:

(vi) Neglect of the Role of Natural Resources:

(vii) Neglect of Differences in Durability of Capital:

(viii) Neglect of Human Capital:

(ix) Effect of Demand Conditions:

(x) Unbalanced Trade:

(xi) Analysis Concerned with Single Country:

(xii) Productivity of Labour:

(xiii) Neglect of Tariffs:

Intra-industry trade refers to the exchange of similar products belonging to the same industry. The term is typically applied to international trade, where the same sorts of goods or services are both imported and exported.

Why do countries at the same time import and export the products of the same industry, or import and export the same types of goods?

According to Nigel Grimwade, "An explanation can't be found within the framework of classical or neo-classical trade theory. The latter predicts only inter-industry specialisation and trade". However, this is often far from the case.

The traditional model of trade wasbegun by the model of Ricardo and the Heckscher–Ohlin model, which tried to elucidate the occurrence of international trade. Both models used the idea of comparative advantage and an evidence of why countries trade. However, many economists have made the point of claiming that these models provide no explanation towards intra-industry trade as under their assumptions countries with identical factor endowments wouldn't trade and produce goods domestically. Hence, as intra-industry trade has developed many economists have looked at other explanations.

One plan to explain IIT was made by Finger (1975), who thought that occurrence of intra-industry trade was “unremarkable” as existing classifications place goods of heterogeneous factor endowments during a single industry. However, evidence shows that even when industries are disaggregated to extremely fine levels IIT still occurs, so this argument are often ignored.

Another potential explanation is provided by Flavey & Kierzkowski (1987). They produced a model that attempted to urge obviate the thought that each one products are produced under identical technical conditions. Their model showed that on the demand side goods are distinguished by the perceived quality of that good and top quality goods are produced under conditions of high capital intensity. However, this explanation has also been dismissed.it's questioned whether the model applies to IIT in the least , because it doesn't address directly trade between goods of comparable factor endowments.

The most comprehensive and widely accepted explanation, a minimum of within theory, is that of Paul Krugman's New Trade Theory. Krugman argues that economies specialise to require advantage of accelerating returns, not following differences in regional endowments (as contended by neoclassical theory). Especially, trade allows countries to concentrate on a limited sort of production and thus reap the benefits of accelerating returns (i.e., economies of scale), but without reducing the variability of products available for consumption.

Yet, Donald Davis believed that both the Heckscher–Ohlin and Ricardian models were still relevant in explaining intra-industry trade.[4] He developed the Heckscher-Ohlin-Ricardo model, which showed that even with constant returns to scale that intra-industry trade could still occur under the normal setting. The Heckscher-Ohlin-Ricardo model explained that countries of identical factor endowments would still trade thanks to differences in technology, as this is able to encourage specialisation and thus trade, in just an equivalent matter that was began within the Ricardian model.

Types-

There are three sorts of intra-industry trade

Although the idea and measurement of intra-industry trade initially focused on trade in goods, especially industrial products, it's also been observed that there's substantial intra-industry trade the international trade of services.[

Intra-industry trade means trade within industries

A measure of the intra-industry trade that takes place between countries is that the Grubel-Lloyd (GL) index.

E.g. If a rustic only exports or imports good X (e.g. sugar) then the GL index for that sector is adequate to 0. On the opposite hand, if a rustic imports exactly the maximum amount of excellent X because it exports, then its GL score for sector would be 1.

Intra-industry trade and stages of development-

Developed economies and rapidly industrialising developing economies (e.g. Hong Kong, China; Singapore; Malaysia and Thailand) tend to interact in additional intra-industry trade

Resource-rich developing economies and fewer Developed Countries tend to possess relatively little intra-industry trade

Economies like Malaysia and Thailand have more intra-industry trade with other developing countries within the same region

Japan has more intra-industry trade with developing economies – it's net importer of commodities and it's also geographically on the brink of several emerging "industrialized" countries like South Korea. There’s increasingly intense competition between Japanese and South Korean manufacturing conglomerate businesses

A major development theme in recent years has been for countries to create a deeper level of complexity into their economy.

Intra-industry trade for developing countries-

We observe that poor countries, albeit similar in terms of income, trade much less with one another compared with rich countries

Countries where overall labour and capital productivity is low have lower wages and produce less differentiated goods and services

Many of those countries are heavily reliant on a little number of products – this provides rise to primary product dependency