UNIT 5

Governance of The Internet of Things

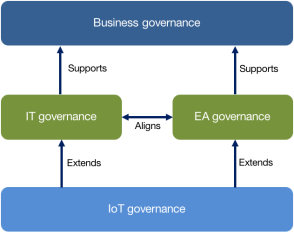

IoT solution governance can be viewed as the application of business governance, IT governance, and enterprise architecture (EA) governance to Internet of Things. In effect, IoT governance is an extension to IT governance, where IoT governance is specifically focused on the lifecycle of IoT devices, data managed by the IoT solution, and IoT applications in an organization’s IT landscape. IoT governance defines the changes to IT governance to ensure the concepts and principles for its distributed architecture are managed appropriately and are able to deliver on the stated business goals.

|

Figure 1

Governance, security and privacy are probably the most challenging issues in the Internet of Things and they have been extensively discussed in many papers. In this section we will try to summarize the capital points of these three aspects of the IoT according to the main contributions proposed in literature. The concepts of IoT Governance, Security and Privacy are also not fully defined and various definitions have been proposed by different government industry and research organizations. Within the EU, ‘Governance’ refers to the rules, processes and behaviour that affect the way in which powers are exercised, particularly as regards openness, participation, accountability, effectiveness and coherence. These five "principles of good governance" reinforce those of subsidiarity and proportionality. The concept of Governance have been already applied to the Internet for specific aspects and there are already organizations like IETF, ICANN, RIRs, ISOC, IEEE, IGF, W3C, which are each responsible and dealing with a specific area.

Notion of governance

The forthcoming advent of the Internet of Things (IoT) raises questions about “governance”. For about 10 years, governance topics have been discussed and debated in relation to many market segments and different organizations/enterprises. It is therefore not surprising that the “governance wave” is also reaching scholarly discourses on the IoT.

“Governance” can be traced back to the Greek term “kybernetes”, usually translated into English as “steersman”, and the Latin word “gubernator” leading to the English notion of “governor”. Consequently, governance addresses aspects of steering or governing behavior.

Different disciplines have addressed governance issues which, in a nutshell, can be summarized as the discussion on the appropriate allocation of duties and responsibilities. It includes the proper structuring of the “organs” concerned, thereby balancing performance-based strategic management and financial/economic control or, in other words:

“Governance, at whatever level of social organization it may take place, refers to conducting the public’s business — to the constellation of authoritative rules, institutions and practices by means of which any collectivity manages its affairs.”

5.1.1 subject to governing principles, private organizations, International regulation and supervisor

An International Framework for Purpose, Structure and Governance of the Internet of Things has been proposed through the CASAGRAS2 project (see Annex 1 - International Framework for Purpose, Structure and Governance of the Internet of Things – Initial Considerations). Primarily, the framework provides the basis for establishing an international foundation for Governance and associated legal underpinning.

The following staged developments are proposed as being necessary for implementing an international framework for Structure and Governance:

- Preparation of IoT Statements of Purpose and Structure within an initial reference document for defining and setting-up an international body for IoT Governance.

- Identification of an international IoT Governance Stakeholder Group.

- Identification and appointment of an International (or Global) Legislator and Regional Legislators and the Governing Body.

- Legislator/Stakeholder agreement on Regulatory approach – prospectively Self-regulation with subsidiarity (central authority or trans-governmental network having subsidiary function in handling tasks or issues that cannot be handled by the self-regulatory authority) rather than international agreement.

- Legislator/Stakeholder review and agreement on IoT Statement of Structure and Purpose.

- Legislator/Stakeholder agreement on international legal framework.

- Legislator/Stakeholder Identification and positioning of trans-governmental networks for IoT Governance.

- Legislator/Stakeholder development and agreement on governance content requirements.

- Legislator/Stakeholder agreement on foundational substantive principles for governance and governance procedures.

- Legislator/Stakeholder agreement on infrastructural requirements and policy for ongoing consideration of infrastructural requirements and attention to robustness, availability, reliability, interoperability, transparency and accountability.

- Legislator/Stakeholder agreement on access to governance procedures and liaison with Internet governance developers.

- Legislator/Stakeholder agreement and pursuance of governance and legal agenda on governance requirements. An essential precursor to pursuing the staged development of an IoT Structure and Governance Framework is an attendant knowledge of the Internet governance. This is required to facilitate a contribution to Internet development per se and to structure an appropriate strategy for collaboration with Internet governance bodies. It is also important as basis for considering parallel and additional issues of governance for the IoT. It is therefore important to review the aspects of governance for the Internet and the critical resources that underpin the success and continued success of the Internet.

5.1.2 substantive principles for IoT governance, Legitimacy and inclusion of stakeholders

Legitimacy and inclusion of stakeholders

Recently developed, the term “legal interoperability” addresses the process of making legal rules cooperate across jurisdictions. This objective can be realized in a matter of degrees, as many options exist between a full harmonization of normative rules and a complete fragmentation of legal systems. Given that these two extremes are not reflected in either the law in the books nor in the law in action, the ideal is usually between the two poles, depending on the given circumstances. As is so often the case, striking the correct balance is of importance: while an excessively high level of interoperability would cause difficulties in the management of the harmonized rules and disregard social and cultural differences, a too-low level could present challenges for smooth (social or economic) interaction.

Based on the common understanding of interoperability being a tool to interconnect networks, legal interoperability can facilitate global communication, reduce costs in cross-border business and drive innovation, thereby creating a level playing field for the next generation of technologies and cultural exchange. From a structural perspective, legal interoperability can be implemented by applying a top-down or a bottom-up approach.

Problems of the Top-Down Approach

A top-down approach necessarily requires the establishment of a global agency, for example the United Nations (UN) or any of the UN special organizations, and usually generates the implementation of large bureaucracies. With regard to the thematically connected Internet governance, the ITU appears to be the most prominent top-down actor.

However, experience over the last 20 years has shown that the ITU was not able to play an influential role in the governing of the Internet. In addition, as the outcome of the World Conference on International Telecommunications in Dubai showed in December 2012 the attempt to agree by consensus on new rules, not even explicitly related to Internet governance, failed. Furthermore, common visions of global norm-setting did not evolve. Accordingly, with regard to the Internet of Things the successful implementation of a top-down approach appears to be unlikely.

Merits of the Bottom-Up Approach

In contrast, a bottom-up process to achieve legal interoperability is based on a step-by-step model encompassing the major entities and persons concerned of the substantive topic in question. Exemplary for a successful bottom-up process, the NETmundial, held in Sao Paulo in April 2014, and the IGF of 2015 hosting the Dynamic Coalition on the IoT need to be mentioned, being considered to be the most important events of the recent past. While in the context of the NET mundial conference the various stakeholders had been granted “equal” rights in the negotiation processes of the final non-binding declaration, the IGF’s activities are gaining influence in the regulatory environment.

Generally speaking, a bottom-up process requires a large amount of coordination, but no harmonization or management by central bodies. Hence, coordination processes can be time-consuming and extremely cumbersome. In the past, the bottom-up approach gained increased acceptance and experiences in different forms lead to improved deliberation and decision-making processes. Nevertheless, the normative environment of this approach still needs further elaboration.

5.1.3 IoT infrastructure governance, robustness, availability, reliability, Transparency, accountability.

The confidential user data IoT devices collect and share fall under the same strict laws and regulations governing data security that all IT systems do, be they laptops, on-premises databases and cloud computing platforms. Adopting a "Secure by Design" approach to device manufacturing, and prioritizing users' privacy are key components in fostering transparency, responsibility and accountability in this Age of IoT.

The IoT trend is transforming virtually every aspect of our lives for the better but connecting the ever-growing number of devices creates additional risks to enterprises and consumers. James Clapper, the U.S. Director of National Intelligence, warned of the risks of the IoT to data privacy, data integrity, or continuity of service in a report presented to the Senate Armed Services Committee that stated, "devices, designed and fielded with minimal security requirements and testing, and an ever-increasing complexity of networks could lead to widespread vulnerabilities in civilian infrastructures and US government systems."

Consumers are right to be concerned about guarding their privacy. When an organization like a hospital connects a new MRI machine to its network, it creates a new cyberattack vector that hackers can use to access or steal data, and even gain control of the hardware itself.

According to Ted Wagner, CISO at SAP NS2, the topics that should be included in any IoT governance program are “software and hardware vulnerabilities, and compliance with security requirements — whether they be regulatory or policy based.”

He refers to a typical use case of when a software flaw is discovered within an IoT device. In this instance, it is important to determine the severity of the flaw. Could it lead to a security incident? How quickly does it need to be addressed? If there is no way to patch the software, is there another way to protect the device or mitigate the risk?

“A good way to deal with IoT governance is to have a board as a governance structure. Proposals are presented to the board, which is normally made up of 6-12 individuals who discuss the merits of any new proposal or change. They may monitor ongoing risks like software vulnerabilities by receiving periodic vulnerability reports that include trends or metrics on vulnerabilities. Some boards have a lot of authority, while others may act as an advisory function to an executive or a decision maker,” Wagner advises.

The objective of this section is to identify the main challenges for the Governance, Security and Privacy in IoT identified by the AC05 cluster projects and during discussions in IERC. Ethical aspects are also considered. A more extensive discussion on ethical aspects in IoT is presented in section Ethics and Internet of Things and some challenges are derived from the analysis in that section. Context based security and privacy This section describes the challenge of designing a security and privacy framework, which is able to address changes in the context (e.g., emergency crisis) or context which do not support the collection and processing of data from sensors. For example, in a surveillance scenario, bad quality images may induce false results of the “smart” functions implemented in IoT framework and hamper the overall decision process in the algorithms used to ensure the security and trust of the system (e.g., level of reputation). The security and privacy framework has to provide features to dynamically adapt access rules and information granularity to the context (e.g., embedding Conditions in access rules or access capability tokens evaluated at access time, see). IoT envisages an enhanced relevance of the context awareness higher needs to support the orchestration and integration of different services, as, for example, envisaged by the DiY (Do it Yourself) sociocultural practice and scalability, manageability and usability. An additional problem is that the automatics of security and privacy technologies defined for a specific context may behave in an incorrect way in a different (or unplanned) context with the consequence of generating vulnerabilities.

Practical Implication

In recent years, the development and deployment of systems and technologies that present a tight coupling between computing devices and the physical environment has grown considerably. Some examples are sensors for monitoring the health of the persons or to increase safety or ergonomics in workplaces, smart grids for energy distribution and intelligent transport systems, which have been also addressed in the iCore project in the use cases described in this deliverable. In many cases, these systems provide services that impact the safety of the citizens. In many cases, these systems or services are not reliable4 (e.g., susceptible to a security attack) the safety of the persons can be put at risk. One example in the Smart Transportation scenario is related to Intelligent Transport Systems where a security attack on the automatic car system for driving can produce car accidents and consequent casualties or harm to citizens. In another scenario an automatic system to provide medicine to a patient can become compromised and deliver the wrong medicine to a patient. In all these systems, the physical environment provides information necessary for achieving many of the important functionalities of the ICT systems through sensors. In turn, systems that use the information from the physical environment can affect the physical environment and the persons living in this environment through actuators. These systems are also called cyber–physical systems (CPSs).

Key Takeaways

- According to Ted Wagner, CISO at SAP NS2, the topics that should be included in any IoT governance program are “software and hardware vulnerabilities, and compliance with security requirements — whether they be regulatory or policy based.”

- Recently developed, the term “legal interoperability” addresses the process of making legal rules cooperate across jurisdictions.

- “A good way to deal with IoT governance is to have a board as a governance structure

- Adopting a "Secure by Design" approach to device manufacturing, and prioritizing users' privacy are key components in fostering transparency, responsibility and accountability in this Age of IoT.

References

- Bernd Scholz-Reiter, Florian Michahelles, “Architecting the Internet of Things”, ISBN 978- 3842-19156-5, Springer.

- Olivier Hersent, David Boswarthick, Omar Elloumi, “The Internet of Things” Key Applications and Protocols, ISBN 978-1-119-99435-0, Wiley Publications.