Unit – 4

Money and National Income

National Income: Meaning and definition

What is saved each year is consumed as regularly as it is I spent every year and almost at the same time. But that is consumed by another person. That part of him the income that rich people spend each year is almost always consumed by an idle guest that part he consumes every year immediately for savings, profits employed as capital and consumed at the same manners but by other people ", Adam Smith

Fisher ' s definition:

Fisher adopted "consumption" as the standard for national income, while Marshall and Pigot considered it production. "

It's a flaw:

Modern definition:

From a modern point of view, Simon Kuznets defines national income as"the net output of goods and services that flow from the national production system into the hands of the end consumer in a year."”

On the other hand, in a United Nations report, national income is determined on the basis of a system of estimates of national income, as a net national product, as a supplement to the share of different factors, and as a country & apos; s net national expenditure over a period of one year. In fact, while estimating national income, any of these three definitions could be used, because if different items were correctly included in the estimate, the same national income could be derived.

Measuring National Income

Components of GNP

Indirect taxes have been eliminated and solid subsidies. In addition, NNP generates national income at base prices. After this, the national income ,Retained earnings, corporate tax, social security ,Contribution and household income.Government we will also send money to your household. In addition, we earn personal income. In the case of income tax when deducted, you get an individual's disposable income.

Is GDP a good measure of welfare?

Injections and Withdrawals

Y≡ C + I + G + NX

S + T + M ≡ I + G + X

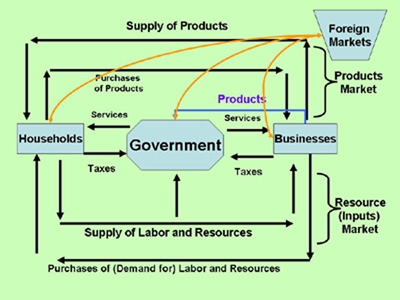

Circular flow of Income

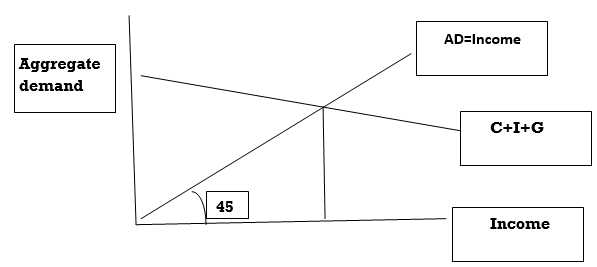

Aggregate Expenditure

Important assumptions

• Prices and wages are fixed in the short term

• Changes in resources and total spending during unemployment

• It is reflected in changes in output and income.

• But in the long run, wages and prices are flexible.

• Therefore, the change in total spending

• It leads to price level changes, but not output.

• We will only look at short-term fluctuations, not long-term fluctuations growth.

Income generation

• Consumption depends on income.

• Suppose 40% of each pound of income is spent on Consumer Goods: C = 0.4Y

• Companies spend £ 20 on investment goods: I = 20

• National income is 100.

• This is in equilibrium. Withdrawal = Savings = 20 = Injection = Investment = 20

• Planned total demand = total revenue Unbalance

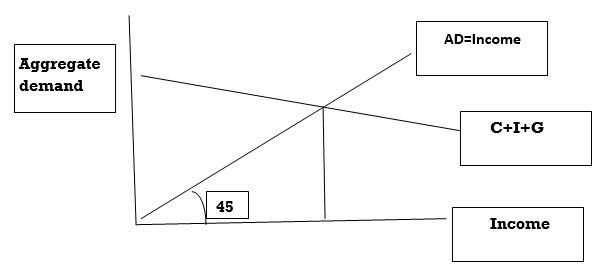

Solving for equilibrium

• Planned spending = income level of income

• Planned spending = C + I = 0.4Y + I

• Setting this equal to income Y gives:

Y = 0.4Y + I, so

Y = I / (1-0.4) = 5I

• The multiplier is 10 = 1 / 0.1 = 1 / marginal propensity to save.

Adjustment Process

• How much income increases when autonomous Increased spending is determined by the multiplier (Richard Kahn, 1931).

• Companies that produce investment goods as I increase Run out of their stock.

• This will increase production over the next period (Equal demand in the previous period).

• Earn extra income and use it for consumers Being a commodity, retailers' inventory is reduced, which triggers them To order more from the manufacturer

Complete the photo

• Two other withdrawals: taxation and imports.

• Initially, government spending and exports were treated as given.

• Taxation and imports depend on the level of income.The government receives 30% of its income as tax, Imports make up 10% of spending.

• Income = Expenditure

• Y = 0.8 * 0.7 * Y + I + G + X-0.1 * Y

• Y = (I + G + X) / (1-0.56 + 0.1)

• Y = (I + G + X) /0.54

Grumpy hive

Still, a huge number of them made them prosperous.Millions of people are trying to supply Mutual desires and vanities. "With greatness. Those who will be resurrectedbGolden age, must be free,nI'm honest about acorns. " Bernard Mandeville (1705)

Paradox of thrift

• At any level if the consumer decides to save more what will happen to my income and income?

• As people save more at the first income level as consumption decreases, so does demand manufacture.

• Therefore, increased savings have reduced production!

• This may only be true in the short term and interest rates are fixed.

• Therefore, savings may be good in the long run, it causes a recession in the short term.

Overview

• GDP can be defined in three different ways: production, spending, or income.

• GDP measurements are incomplete, costly and time consuming. Many economic activity such as housework and housework is not measured underground economy. Therefore, GDP is an incomplete indicator standard of living.

• However, the year-to-year changes in GDP the state of the business cycle.

• In equilibrium, planned spending must be equal to actual spending economy.

• Increased personal frugality can lead to decreased, all other things being equal with total output, and therefore with total savings.

Three views of national income and their relationships. The concept is as follows:

The concept of national income

This is the sum of all final goods and services produced in the economy in a year. In W.C.'s words, Peterson, "Gross National Product may be defined as the current market value of all goods and services produced by the economy during the period of income." There are two ways to avoid double counting when estimating GNP.

GNP calculated in this way excludes the value of the import because the cost is automatically deducted from the production value of the industry using the value of the import. To get Gross National Product, you need to deduct depreciation from the total "value added". The "added value" method and the "final product" method give the same result. The former considers the flow of production through each process while the "final product" method counts the quantity of goods delivered at the end of a particular period and appropriates the goods still in transit at the beginning and end. Adjust to. Of the period the "added value" method follows normal corporate accounting procedures because all companies record the value of their products and the value of the materials used. The "final product" method suffers from many difficulties in that it requires the actual prod Gross National Product (GDP), Gross National Product (GNP), Net Gross National Product (NNI), Adjusted Gross National Product, etc., in economics to estimate gross national product and production in a country or region. A variety of high indicators are used. (NNIs are tuned for natural resource depletion – also known as NNIs for factor cost). Both are of particular interest in counting the total amount of goods and services produced within the economy and in various sectors. Boundaries are usually defined by geography or citizenship, also as the country's total income, and limit the goods and services that are counted. For example, some measures count only the goods and services that are exchanged for money, excluding the bartered goods, while others try to include them by imposing monetary value on the bartered goods. There is also National accounts

A large amount of data collection and calculation is required to reach the total production figures of goods and services in a large area such as a country. Although several attempts were made to estimate national accounts by the 17th century, [2] systematic maintenance of national accounts, including these figures, began in the United States and some European countries in the 1930s. It was. The driving force behind its key statistical efforts is the rise of Clutch plague and Keynesian economics, which defines the government's greater role in economic management and provides accurate information to the government to advance its intervention in the economy. I needed to. Provide as much information as possible.

In order to count goods and services, we need to assign value to them. The value that national income and output measurements assign to a good or service is its market value, the price you get when you buy or sell. The actual utility of the product (its value in use) is not measured – assume that the value in use differs from its market value.

Three strategies are used to obtain the market value of all products and services produced: product (or production) method, expenditure method, and income method. The Product Law examines the economy by industry. The total output of the economy is the sum of the output of all industries. However, because the output of one industry may be used by another industry and become part of the output of that second industry, the value of each industry's output should not be counted twice. Use added value instead. In other words, the difference in value between what it produces and what it incorporates. The total value produced by the economy is the sum of the values added by all industries.

Spending methods are based on the idea that all products are purchased by someone or some organization. Therefore, we sum the total amount that people and organizations spend to buy things. This amount should be equal to all the values generated. Individual spending, corporate spending, and government spending are usually calculated separately and summed up to total spending. In addition, it is necessary to introduce an amendment period in consideration of imports and exports outside the boundary.Their total revenue must be the total value of the product, as they are only paid for the market value of their product. Wages, owners' income, and corporate profits are the main subdivisions of income.

How to measure national income

Output

The output approach focuses on finding the total output of a country by directly finding the total value of all goods and services produced by the country.

Due to the complexity of multiple stages in the production of a good or service, only the ultimate value of the good or service is included in the total production. This avoids a problem called "double counting" where the total value of goods is included several times in a country's production by repeatedly counting at several stages of production. In the meat production example, the value of goods from a farm could be $ 10, then $ 30 from a butcher, and $ 60 from a supermarket. The value that should be included in the final national production should be $ 60, not the sum of all these numbers, $ 100. The added values at each stage of production compared to the previous stage are $ 10, $ 20, and $ 30, respectively. The sum of them provides another way to calculate the value of the final output.

The main formulas are:

Spending

The spending approach is basically an output accounting method. It focuses on finding the country's total production by finding the total amount spent. This is acceptable to economists, as the sum of all commodities, as well as income, is equal to the total amount spent on the commodities. The basic formula for domestic output is to take all the various fields in which money is spent in the region and combine them to obtain the total output.

{\ displaystyle \ mathrm {GDP} = C + G + I + \ left (\ mathrm {X} -M \ right)} {\ mathrm {GDP}} = C + G + I + \ left ({\ mathrm { X}} -M \ right)

Where:

C = consumption household expenditure / consumption expenditure personal

I = total private sector investment

G = Government consumption and total investment expenditure

X = total export of goods and services

M = Total import of goods and services

Note: (X-M) is often described as XN or NX, both representing "net exports".

The name of the measure consists of either the word "Gross" or "Net", the word "National" or "Domestic", or the word "Product", "Income", or "Expenditure". Will be done. ". All of these terms can be explained individually."Gloss" means the entire product, regardless of its subsequent use. That is, the depletion or obsolescence of a country's fixed capital assets. The "net" indicates the amount of product that is actually available for consumption or new investment.

"Domestic" means that the boundaries are geographical. That is, it counts all goods and services produced within the border, regardless of who they are.

"Nationality" means that boundaries are defined by citizenship (nationality). We count all goods and services produced by the people of the country (or the companies they own), regardless of where their production physically takes place.

The production of French-owned cotton factories in Senegal is counted as part of Senegal's national figures, but as part of France's national figures.

"Product," "Income," and "Expenditure" refer to the three counting methods described earlier: the product, income, and expenditure approach. However, these terms are used loosely.

"Product" is a general term and is often used when one of the three approaches is actually used. The word "product" may be used, followed by additional symbols or phrases to indicate the methodology. So, for example, you get structures such as "Gross Domestic Product", "GDP (Income)", and "GDP (I)".

"Income" here is the income approach was used.

"Expenditure" specifically means that the spending approach was used.

Note that in theory, all three counting methods give the same final number. However, in reality, there are subtle differences from the three methods for several reasons, such as inventory level changes and statistical errors. For example, one problem is that an in-stock item has been produced (and therefore included in the product) but not yet sold (and therefore not yet included in the expenditure). Similar timing issues are due to the value (product) of the product produced and the factors that produced it, especially when the input is purchased with credit and wages are often collected after a period of time of production that can cause slight discrepancies between (income)

Gross domestic product (GDP) and gross national product(GNP)

GDP

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the sum of the monetary or market value of all finished products and services produced within a border over a particular period of time. It serves as a comprehensive scorecard for the economic health of a particular country as a broad measure of overall domestic production.

For example, in the United States, the government publishes annual GDP estimates for each accounting quarter and calendar year. The individual datasets included in this report are effectively provided, so the data is adjusted for price fluctuations, minus inflation. In the United States, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) of the US Department of Commerce uses data identified through surveys of retailers, manufacturers, and builders to look at trade flows and calculate GDP.

Important points

Despite the limitations of GDP, GDP is an important tool for policy makers, investors and businesses to make strategic decisions.

GNP

Gross National Product (GNP) is an estimate of the sum of all final products and services produced in a particular period by means of production owned by a resident of the country. GNP is usually calculated from the sum of consumer spending, private domestic investment, government spending, net exports, and income earned by residents from foreign investment minus income earned by foreign residents in the domestic economy. I will. Net exports represent the difference between what a country exports minus imports of goods and services. 1

GNP is associated with another important economic indicator called Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This takes into account all production produced within the border, regardless of the owner of the means of production. GNP starts with GDP, adds the investment income of the resident from the overseas investment, and deducts the investment income of the foreign resident obtained in Japan. (For related materials, see "About GDP and GNP") 1

Important points

As an example, the table below shows some of the US GDP and GNP, and NNI data.

NDP: Net domestic product, like NNP, is defined as "gross domestic product (GDP) minus capital depreciation"

GDP per capita: Gross domestic product per capita is the average value of per capita production and is also the average income.

National income and welfare

GDP per capita (per capita) is often used as a measure of human welfare. Countries with high GDP are more likely to score high on other welfare indicators such as life expectancy.

GDP measurements usually exclude unpaid economic activity, most importantly domestic work such as childcare. This leads to distortion. For example, the income of a paid nanny contributes to GDP, but the time unpaid parents spend caring for their children does not, even if they both have the same economic activity.

GDP does not consider the inputs used to generate the output. For example, if everyone worked twice as long, GDP could double, but this does not necessarily mean that workers are better because they have less leisure time. Similarly, the environmental impact of economic activity is not measured in GDP calculations.

Green GNP

Green GNP - Is an economic and environmental accounting framework that measures national wealth by taking into account depletion of natural resources and environmental degradation and investment in environmental aid.

What is Green GDP?

Green Gross Domestic Product, or Green GDP for short, is an indicator of economic growth that takes environmental factors into account along with national standard GDP. Green GDP takes into account the loss and cost of biodiversity due to climate change. Physical indicators such as "annual carbon dioxide" and "waste per capita" may be aggregated into indicators such as "sustainable development indicator

What is the Rationale behind Green GDP?

Standard GDP measurements are limited because they are indicators of economic growth and a desirable standard of living. Standard GDP measures only total economic output and there is no way to identify the wealthy or wealthy people that are generated due to economic output. Normal GDP also has no way of knowing if the income levels generated in a country are sustainable. Green GDP is required to overcome this limitation. The capital is not considered relevant and is not well explained in GDP. Policy makers and economic planners do not fully value the potential future benefits of protected environment projects in relation to costs. The positive benefits that can arise from forests and farmlands are not taken into account due to operational difficulties in measuring and valuing such assets. Also, the impact of depletion of natural resources needed to run the economy as described in standard GDP measurements.

How is Green GDP Calculated?

Green GDP is calculated by subtracting net natural capital consumption from the standard GDP. This includes resource depletion, environmental degradation and protective environmental initiatives. These calculations can alternatively be applied to the net domestic product (NDP), which subtracts the depreciation of capital from GDP. In every case, it is required to convert any resource extraction activity into a monetary value since they are expressed in this manner through national accounts.

GDP vs green GDP

Critics of the calculations that take into account environmental factors point out that it is difficult to quantify some of the indicated outputs. This is a particular difficulty in cases where the environmental asset does not exist in a traditional market and is therefore not negotiable. Ecosystem services are an example of this type of resource. In the event that the valuation is made indirectly, there is a possibility that the calculations may rely on speculation or hypothetical assumptions.

Those who support these corrected aggregates can answer this objection in two ways. First, as our technological capabilities have grown, more accurate valuation methods have been and will continue to develop. Second, while measurements may not be perfect in cases of natural non-market activities, the adjustments they entail are still a preferable alternative to traditional GDP.

Net National Product

Net National Product (NNP) is obtained by adjusting depreciation at GNP. As mentioned above, GNP is the sum of the amount of production and the income received by a domestic resident of a country in a year. Over the past year, the available plants and machinery (capital) have been worn and criticized. Such a decrease in capital assets due to wear is measured as "capital depreciation". NNP is obtained by subtracting the value of such depreciation from GNP.

That is GNP - Depreciation = NNP

Per Capita Income

Per capita income (or) output per person is an indicator to show the living standards of people in a country. If real PCI increases, it is considered to be an improvement in the overall living standard of people. PCI is arrived at by dividing the GDP by the size of population. It is also arrived by making some adjustment with GDP.

GDP=PCI / Total number of people in a country

Key Takeaways:

Meaning: -

Money may be anything chosen as the medium of exchange. According to some economist money is anything that performs the function of money. It is something which is widely accepted in payment for goods and services and in settlement of debts. In a modern society for commodities are expressed and valued in terms of money. In a wider sense, the term money includes all medium of exchange – Gold, Silver, Copper, Paper, Cheques, Commercial Bills of exchange, etc.

Functions of Money: -

Money performs various functions. Mainly the functions of money can be classified into three groups’ namely

(i) Primary functions (ii) Secondary function (iii) Contingent functions

1) Primary function: Primary functions are basic or fundamental function of money. In fact, they are the original functions of money which ensure smooth working of the economy. Following are the primary functions:

a) Medium of exchange: Money acts as an effective medium of exchange. It facilitates exchange of goods and services. Everything is bought and sold with help of money. By performing as the medium of exchange, money removes the difficulties of barter system.

b) Measure of value: Money serves as a common measure of value. The value of all goods and services are measured in terms of money. In other words, pieces of all goods and services are expressed in terms money.

Key Points: - Exchange and Measure

2) Secondary function: Secondary functions are those functions which are derived from primary function.

a) Standard of deferred payment: Money acts as an effective standard of deferred payments. Deferred payments refer to payment to be made in future. Deferred payments have become the day-to-day activity in modern society. Money facilitates all kinds of credit transactions. Both, borrowings as well as lending are done in terms of money. All kinds of Hire purchase transactions are carried out in terms of money. As money enjoys the attributes of stability, Durability and General acceptability, it acts as a better standard of deferred payments.

b) Store of value: Money serves as a store of value. Savings were discouraged under the barter system due to lack of store of value. With inventions of money, it is possible to save. At present all savings are done in terms of money. Bank deposits represent the savings of the people. Moreover, money can be easily converted into any other Marketable assets like Land, Machinery, Plant, etc. Thus, it facilitates capital accumulation. Money being the most liquid assets, it acts as a better store of value than any other assets.

c) Transfer of value: Money acts as a means of transferring purchasing power. Money facilitates transfer of value from one person to another person & one place to another place. As money enjoys general acceptability, a person can dispose of his property in Delhi and purchase new property at Mumbai. Instrument like cheques and bank drafts enable such transfer easy and quick.

Key Points: - Payment, Store of value, Transfer

3) Contingent function: In additions to the above functions, money has to performs certain special function known as contingent functions –

DEMANDS FOR MONEY – CLASSICAL AND KEYNESIAN APPROACH

The demand for money arises from two important functions of money. the primary is that money acts as a medium of exchange and therefore the second is that it's a store of value. Thus, individuals and businesses wish to carry money partly in cash and partly within the sort of assets.

What explains changes within the demand for money? There are two views on this issue. the primary is that the “scale” view which is said to the impact of the income or wealth level upon the demand for money. The demand for money is directly associated with the income level. the higher the income level, the greater are going to be the demand for money.

The second is that the “substitution” view which is said to relative attractiveness of assets which will be substituted for money. consistent with this view, when alternative assets like bonds become unattractive thanks to fall in interest rates, people like better to keep their assets in cash, and therefore the demand for money increases, and the other way around.

The scale and substitution view combined together are accustomed explain the nature of the demand for money which has been split into the transactions demand, the precautionary demand and therefore the speculative demand. There are three approaches to the demand for money: the classical, the Keynesian, and therefore the post-Keynesian. We discuss these approaches below.

The Classical Approach:

The classical economists didn't explicitly formulate demand for money theory but their views are inherent within the quantity theory of money. They emphasized the transactions demand for money in terms of the rate of circulation of cash. this is often because money acts as a medium of exchange and facilitates the exchange of products and services. In Fisher’s “Equation of Exchange”.

MV=PT

Where M is that the total quantity of cash, V is its velocity of circulation, P is that the price level, and T is that the total amount of goods and services exchanged for money.

The right-hand side of this equation PT represents the demand for money which, in fact, “depends upon the worth of the transactions to be undertaken within the economy, and is adequate to a constant fraction of these transactions.” MV represents the supply of money which is given and in equilibrium equals the demand for money. Thus, the equation becomes

Md = PT

This transactions demand for money, in turn, is decided by the extent of full employment income. this is often because the classicists believed in Say’s Law whereby supply created its own demand, assuming the full employment level of income. Thus, the demand for money in Fisher’s approach may be a constant proportion of the extent of transactions, which successively, bears a continuing relationship to the extent of value. Further, the demand for money is linked to the volume of trade happening in an economy at any time.

Thus, its underlying assumption is that individuals hold money to buy goods.

But people also hold money for other reasons, like to earn interest and to supply against unforeseen events. it's therefore, impracticable to say that V will remain constant when M is modified. the foremost important thing about money in Fisher’s theory is that it's transferable. But it doesn't explain fully why people hold money. It doesn't clarify whether to incorporate as money such items as time deposits or savings deposits that aren't immediately available to pay debts without first being converted into currency.

It was the Cambridge cash balance approach which raised an extra question: Why do people actually want to carry their assets within the form of money? With larger incomes, people want to form larger volumes of transactions which larger cash balances will, therefore, be demanded.

This equation tells us that “other things being equal, the demand for money in normal terms would be proportional to the nominal level of income for every individual The Cambridge demand equation for money is

Md=kPY

where Md is that the demand for money which must equal the supply to money (Md=Ms) in equilibrium within the economy, k is that the fraction of the important money income (PY) which individuals wish to carry in cash and demand deposits or the ratio of money stock to income, P is that the price level, and Y is that the aggregate real income., and hence for the mixture economy also.”

Its Critical Evaluation:

This approach includes time and saving deposits and other convertible funds within the demand for money. It also stresses the importance of factors that make money more or less useful, like the costs of holding it, uncertainty about the future then on. But it says little about the character of the relationship that one expects to prevail between its variables, and it doesn't say too much about which ones could be important.

One of its major criticisms arises from the neglect of store useful function of cash. The classicists emphasized only the medium of exchange function of money which simply acted as a go-between to facilitate buying and selling. For them, money performed a neutral role within the economy. it had been barren and wouldn't multiply, if stored within the form of wealth.

This was an erroneous view because money performed the “asset” function when it's transformed into other sorts of assets like bills, equities, debentures, real assets (houses, cars, TVs, then on), etc. Thus, the neglect of the asset function of cash was the main weakness of classical approach to the demand for money which Keynes remedied.

The Keynesian Approach: Liquidity Preference:

Keynes in his General Theory used a replacement term “liquidity preference” for the demand for money. Keynes suggested three motives which led to the demand for money in an economy: (1) the transactions demand, (2) the precautionary demand, and (3) the speculative demand.

The Transactions Demand for Money:

The transactions demand for money arises from the medium of exchange function of money in making regular payments for goods and services. consistent with Keynes, it relates to “the need of money for the present transactions of private and business exchange” it's further divided into income and business motives. The income motive is supposed “to bridge the interval between the receipt of income and its disbursement.”

Similarly, the business motive is supposed “to bridge the interval between the time of incurring business costs which of the receipt of the sale proceeds.” If the time between the incurring of expenditure and receipt of income is little, less cash is going to be held by the people for current transactions, and the other way around. there’ll, however, be changes within the transactions demand for money depending upon the expectations of income recipients and businessmen. They depend on the level of income, the rate of interest, the business turnover, the traditional period between the receipt and disbursement of income, etc.

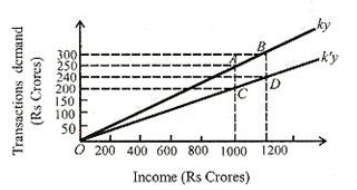

Given these factors, the transactions demand for money may be a direct proportional and positive function of the extent of income, and is expressed as

L1 = kY

Where L1 is that the transactions demand for money, k is that the proportion of income which is kept for transactions purposes, and Y is that the income.

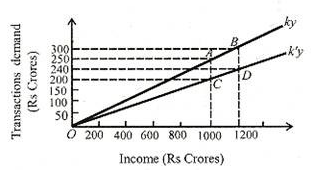

This equation is illustrated in Figure 70.1 where the line kY represents a linear and proportional relation between transactions demand and therefore the level of income. Assuming k= 1/4 and income Rs 1000 crores, the demand for transactions balances would be Rs 250 crores, at point A. With the rise in income to Rs 1200 crores, the transactions demand would be Rs 300 crores at point В on the curve kY.

If the transactions demand falls because of a change in the institutional and structural conditions of the economy, the value of к is reduced to mention, 1/5, and therefore the new transactions demand curve is kY. It shows that for income of Rs 1000 and 1200 crores, transactions balances would Rs 200 and 240 crores at points С and D respectively within the figure. “Thus, we conclude that the chief determinant of changes within the actual amount of the transactions balances held is changes in income. Changes within the transactions balances are the results of movements along a line like kY instead of changes within the slope of the line. within the equation, changes in transactions balances are the results of changes in Y instead of changes in k.”

Interest Rate and Transactions Demand:

Regarding the rate of interest because the determinant of the transactions demand for money Keynes made the LT function interest inelastic. But the acknowledged that the “demand for money within the active circulation is additionally some extent a function of the rate of interest, since a higher rate of interest may cause a more economical use of active balances.” “However, he didn't stress the role of the rate of interest during this a part of his analysis, and lots of some his popularizes ignored it altogether.” In recent years, two post-Keynesian economists William J. Baumol and James Tobin have shown that the rate of interest is a crucial determinant of transactions demand for money.

They have also pointed out the relationship, between transactions demand for money and income isn't linear and proportional. Rather, changes in income result in proportionately smaller changes in transactions demand.

Transactions balances are held because income received once a month isn't spent on the same day. In fact, a private spread his expenditure evenly over the month. Thus, some of cash meant for transactions purposes are often spent on short-term interest-yielding securities. it's possible to “put funds to figure for a matter of days, weeks, or months in interest-bearing securities like U.S. Treasury bills or commercial paper and other short-term money market instruments.

The problem here is that there's a cost involved in buying and selling. One must weigh the financial cost and inconvenience of frequent entry to and exit from the market for securities against the apparent advantage of holding interest-bearing securities in situ of idle transactions balances.

Among other things, the value per purchase and sale, the speed of interest, and therefore the frequency of purchases and sales determine the profitability of switching from ideal transactions balances to earning assets. Nonetheless, with the value per purchase and sale given, there's clearly some rate of interest at which it becomes profitable to modify what otherwise would be transactions balances into interest-bearing securities, albeit the amount that these funds could also be spared from transactions needs is measured only in weeks. the higher the rate of interest, the larger will be the fraction of any given amount of transactions balances which will be profitably diverted into securities.”

The structure of cash and short-term bond holdings is shown in Figure 70.2 (A), (B) and (C). Suppose a private receives Rs 1200 as income on the first of every month and spends it evenly over the month. The month has four weeks. His saving is zero.

Accordingly, his transactions demand for money in each week is Rs 300. So, he has Rs 900 idle money within the first week, Rs 600 within the second week, and Rs 300 within the third week. He will, therefore, convert this idle money into interest bearing bonds, as illustrated in Panel (B) and (C) of Figure 70.2. He keeps and spends Rs 300 during the first week (shown in Panel B), and invests Rs 900 in interest-bearing bonds (shown in Panel C). On the primary day of the second week, he sells bonds worth Rs. 300 to cover cash transactions of the second week and his bond holdings are reduced to Rs 600.

Similarly, he will sell bonds worth Rs 300 within the beginning of the third and keep the remaining bonds amounting to Rs 300 which he will sell on the first day of the fourth week to satisfy his expenses for the last week of the month. the amount of cash held for transactions purposes by the individual during each week is shown in saw-tooth pattern in Panel (B), and therefore the bond holdings in each week are shown in blocks in Panel (C) of Figure 70.2.

The modern view is that the transactions demand for money is a function of both income and interest rates which may be expressed as

L1 = f (Y, r).

This relationship between income and rate of interest and therefore the transactions demand for money for the economy as an entire is illustrated in Figure 3. We saw above that LT = kY. If y=Rs 1200 crores and k= 1/4, then LT = Rs 300 crores.

This is shown as Y1 curve in Figure 70.3. If the income level rises to Rs 1600 crores, the transactions demand also increases to Rs 400 crores, given k = 1/4. Consequently, the transactions demand curve shifts to Y2. The transactions demand curves Y1, and Y2 are interest- inelastic so long because the rate of interest doesn't rise above r8 per cent.

As the rate of interest starts rising above r8, the transactions demand for money becomes interest elastic. It indicates that “given the cost of switching into and out of securities, at rate of interest above 8 per cent is sufficiently high to draw in some amount of transaction balances into securities.” The backward slope of the K, curve shows that at still higher rates, the transaction demand for money declines.

Thus, when the rate of interest rises to r12, the transactions demand declines to Rs 250 crores with an income level of Rs 1200 crores. Similarly, when the value is Rs 1600 crores the transactions demand would decline to Rs 350 crores at r12 rate of interest. Thus, the transactions demand for money varies directly with the level of income and inversely with the speed of interest.

The Precautionary Demand for Money:

The Precautionary motive relates to “the desire to produce for contingencies requiring sudden expenditures and for unforeseen opportunities of advantageous purchases.” Both individuals and businessmen keep take advantage reserve to satisfy unexpected needs. Individuals hold some cash to supply for illness, accidents, unemployment and other unforeseen contingencies.

Similarly, businessmen keep cash in reserve to tide over unfavourable conditions or to gain from unexpected deals. Therefore, “money held under the precautionary motive is very like water kept in reserve during a water tank.” The precautionary demand for money depends upon the level of income, and business activity, opportunities for unexpected profitable deals, availability of cash, the cost of holding liquid assets in bank reserves, etc.

Keynes held that the precautionary demand for money, like transactions demand, was a function of the extent of income. But the post-Keynesian economists believe that like transactions demand, it's inversely associated with high interest rates. The transactions and precautionary demand for money are going to be unstable, particularly if the economy isn't at full employment level and transactions are, therefore, but the maximum, and are liable to fluctuate up or down.

Since precautionary demand, like transactions demand may be a function of income and interest rates, the demand for money for these two purposes is expressed within the single equation LT=f (Y, r)9. Thus, the precautionary demand for money also can be explained diagrammatically in terms of Figures 2 and 3.

The Speculative Demand for Money:

The speculative (or asset or liquidity preference) demand for money is for securing profit from knowing better than the market what the longer term will bring forth”. Individuals and businessmen having funds, after keeping enough for transactions and precautionary purposes, wish to make a speculative gain by investing fettered. Money held for speculative purposes may be a liquid store of value which may be invested at an opportune moment in interest-bearing bonds or securities.

Bond prices and therefore the rate of interest is inversely associated with one another. Low bond prices are indicative of high interest rates, and high bond prices reflect low interest rates. A bond carries a fixed rate of interest. as an example, if a bond of the worth of Rs 100 carries 4 per cent interest and therefore the market rate of interest rises to eight per cent, the worth of this bond falls to Rs 50 within the market. If the market rate of interest falls to 2 per cent, the value of the bond will rise to Rs 200 within the market.

This can be figured out with the assistance of the equation

V = R/r

Where V is that the current market value of a bond, R is that the annual return on the bond, and r is that the rate of return currently earned or the market rate of interest. So, a bond worth Rs 100 (V) and carrying a 4 per cent rate of interest (r), gets an annual return (R) of Rs 4, that is,

V=Rs 4/0.04=Rs 100. When the market rate of interest rises to 8 per cent, then V=Rs 4/0.08=Rs50; when it falls to 2 per cent, then V=Rs 4/0.02=Rs 200.

Thus, individuals and businessmen can gain by buying bonds worth Rs 100 each at the market value of Rs 50 each when the rate of interest is high (8 per cent), and sell them again once they are dearer (Rs 200 each when the speed of interest falls (to 2 per cent).

According to Keynes, it's expectations about changes in bond prices or within the current market rate of interest that determine the speculative demand for money. In explaining the speculative demand for money, Keynes had a normal or critical rate of interest (rc) in mind. If the present rate of interest (r) is above the “critical” rate of interest, businessmen expect it to fall and bond price to rise. They will, therefore, buy bonds to sell them in future when their prices rise so as to realize thereby. At such times, the speculative demand for money would fall. Conversely, if the present rate of interest happens to be below the critical rate, businessmen expect it to rise and bond prices to fall. They will, therefore, sell bonds within the present if they have any, and therefore the speculative demand for money would increase.

Thus, when r > r0, an investor holds all his liquid assets in bonds, and when r < r0 his entire holdings enter money. But when r = r0, he becomes indifferent to carry bonds or money.

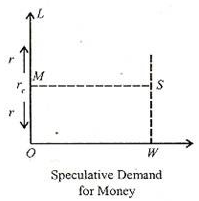

Thus, relationship between an individual’s demand for money and therefore the rate of interest is shown in Figure 70.4 where the horizontal axis shows the individual’s demand for money for speculative purposes and therefore the current and important interest rates on the vertical axis. The figure shows that when r is larger than r0, the asset holder puts all his cash balances in bonds and his demand for money is zero.

This is illustrated by the LM portion of the vertical axis. When r falls below r0, the individual expects more capital losses on bonds as against the interest yield. He, therefore, converts his entire holdings into money, as shown by OW within the figure. This relationship between an individual asset holder’s demand for money and therefore the current rate of interest gives the discontinuous step demand for money curve LMSW.

For the economy as an entire the individual demand curve is often aggregated on this presumption that individual asset-holders differ in their critical rates r0. it's smooth curve which slopes downward from left to right, as shown in Figure 70.5.

Thus, the speculative demand for money is a decreasing function of the rate of interest. the higher the rate of interest, the lower the speculative demand for money and therefore the lower the rate of interest, the higher the speculative demand for money. It is often expressed algebraically as Ls = f (r), where Ls is that the speculative demand for money and r is that the rate of interest.

Geometrically, it's shows in Figure 70.5. The figure shows that at a very high rate of interest rJ2, the speculative demand for money is zero and businessmen invest their cash holdings fettered because they believe that the rate of interest cannot rise further. because the rate of interest falls to say, r8 the speculative demand for money is OS. With a further fall within the rate of interest to r6, it rises to OS’. Thus, the form of the Ls curve shows that because the rate of interest rises, the speculative demand for money declines; and with the fall in the rate of interest, it increases. Thus, the Keynesian speculative demand for money function is very volatile, depending upon the behaviour of interest rates.

Liquidity Trap:

Keynes visualised conditions during which the speculative demand for money would be highly or maybe totally elastic so that changes within the quantity of money would be fully absorbed into speculative balances. this is often the famous Keynesian liquidity trap. during this case, changes within the quantity of money have no effects in the least on prices or income. according to Keynes, this is often likely to happen when the market rate of interest is very low in order that yields on bond, equities and other securities also will be low.

At a really low rate of interest, like r2, the Ls curve becomes perfectly elastic and therefore the speculative demand for money is infinitely elastic. This portion of the Ls curve is known as the liquidity trap. At such a low rate, people prefer to keep money in cash instead of invest fettered because purchasing bonds will mean a definite loss. People won't buy bonds so long as the rate of interest remain at the low level and that they will be expecting the speed of interest to return to the “normal” level and bond prices to fall.

According to Keynes, because the rate of interest approaches zero, the risk of loss in holding bonds becomes greater. “When the price of bonds has been bid up so high that the rate of interest is, say, only 2 per cent or less, a really small decline within the price of bonds will wipe out the yield entirely and a rather further decline would result in loss of a part of the principal.” Thus, the lower the rate of interest, the smaller the earnings from bonds. Therefore, the greater the demand for cash holdings. Consequently, the Ls curve will become perfectly elastic.

Further, consistent with Keynes, “a long-term rate of interest of two per cent leaves more to fear than to hope, and offers, at an equivalent time, a running yield which is only sufficient to offset a really small measure of fear.” This makes the Ls curve “virtually absolute within the sense that almost everybody prefers cash to holding a debt which yields so low a rate of interest.”

Prof. Modigliani believes that an infinitely elastic Ls curve is possible in a period of great uncertainty when price reductions are anticipated and therefore the tendency to invest in bonds decreases, or if there prevails “a real scarcity of investment outlets that are profitable at rates of interest above the institutional minimum.”

The phenomenon of liquidity trap possesses certain important implications.

First, the monetary authority cannot influence the rate of interest even by following a cheap money policy. a rise within the quantity of cash cannot lead to a further decline within the rate of interest during a liquidity-trap situation. Second, the rate of interest cannot fall to zero.

Third, the policy of a general wage cut can't be efficacious within the face of a perfectly elastic liquidity preference curve, like Ls in Figure 70.5. No doubt, a policy of general wage cut would lower wages and prices, and thus release money from transactions to speculative purpose, the rate of interest would remain unaffected because people would hold money due to the prevalent uncertainty within the money market. Last, if new money is made, it instantly goes into speculative balances and is put into bank vaults or cash boxes rather than being invested. Thus, there's no effect on income. Income can change with none change in the quantity of money. Thus, monetary changes have a weak effect on economic activity under conditions of absolute liquidity preference.

The Total Demand for Money:

According to Keynes, money held for transactions and precautionary purposes is primarily a function of the extent of income, LT=f (F), and therefore the speculative demand for money may be a function of the rate of interest, Ls = f (r). Thus, the total demand for money may be a function of both income and therefore the interest rate:

LT + LS = f (Y) + f (r)

or L = f (Y) + f (r)

or L=f (Y, r)

Where L represents the entire demand for money.

Thus, the entire demand for money can be derived by the lateral summation of the demand function for transactions and precautionary purposes and therefore the demand function for speculative purposes, as illustrated in Figure 70.6 (A), (B) and (C). Panel (A) of the Figure shows ОТ, the transactions and precautionary demand for money at Y level of income and different rates of interest. Panel (B) shows the speculative demand for money at various rates of interest. it's an inverse function of the rate of interest.

For instance, at r6 rate of interest it's OS and as the rate of interest falls to r the Ls curve becomes perfectly elastic. Panel (C) shows the entire demand curve for money L which may be a lateral summation of LT and Ls curves: L=LT+LS. for example, at rb rate of interest, the entire demand for money is OD which is that the sum of transactions and precautionary demand ОТ plus the speculative demand TD, OD=OT+TD. At r2 rate of interest, the total demand for money curve also becomes perfectly elastic, showing the position of liquidity trap.

SUPPLY OF MONEY

Definition of money Supply

The supply of money is a stock at a specific point of time, though it conveys the idea of a flow over time. The term ‘the supply of money’ is synonymous with such terms as ‘money stock’, ‘stock of money’, ‘money supply’ and ‘quantity of money’. the supply of money at any moment is that the total amount of money within the economy.

There are three alternative views regarding the definition or measures of money supply. the foremost common view is related to the traditional and Keynesian thinking which stresses the medium of exchange function of cash. consistent with this view, money supply is defined as currency with the general public and demand deposits with commercial banks.

Demand deposits are savings and current accounts of depositors in a commercial bank. they're the liquid kind of money because depositors can draw cheques for any amount lying in their accounts and therefore the bank has got to make cash on demand. Demand deposits with commercial banks plus currency with the general public are together denoted as M1, the money supply. this is often considered a narrower definition of the cash supply.

The second definition is broader and is related to the modem quantity theorists headed by Friedman. Professor Friedman defines the cash supply at any moment of time as “literally the number of dollars people are carrying around in their pockets, the number of dollars they need to their credit at banks or dollars they need to their credit at banks in the form of demand deposits, and also commercial bank time deposits.” Time deposits are fixed deposits of customers in a commercial bank. Such deposits earn a fixed rate of interest varying with the period of time that the amount is deposited. Money can be withdrawn before the expiry of that period by paying a penal rate of interest to the bank.

So, time deposits possess liquidity and are included within the money supply by Friedman. Thus, this definition includes M1 plus time deposits of economic banks within the supply of cash. This wider definition is characterised as M2 in America and M3 in Britain and India. It stresses the store useful function of money or what Friedman says, ‘a temporary abode of purchasing power’.

The third definition is that the broadest and is related to Gurley and Shaw. They include within the supply of money, M2 plus deposits of savings banks, building societies, loan associations, and deposits of other credit and financial institutions.

The choice between these alternative definitions of the money supply depends on two considerations. One a particular choice of definition may facilitate or blur the analysis of the varied motives for holding cash; and two from the point of view of monetary policy, an appropriate definition should include the world over which the monetary authorities can have direct influence. If these two criteria are applied, none of the three definitions is wholly satisfactory.

The first definition of money supply could also be analytically better because M1 may be a sure medium of exchange. But M1 is an inferior store useful because it earns no rate of interest, as is earned by time deposits. Further, the central bank can have control over a narrower area if only demand deposits are included in the funds.

The second definition that has time deposits (M,) within the supply of money is less satisfactory analytically because “in a highly developed financial structure, it's important to consider separately the motives for holding means of payment and time deposits.” Unlike demand deposits, time deposits aren't a prefect liquid sort of money.

This is because the amount lying in them are often withdrawn immediately by cheques. Normally, it can't be withdrawn before the due date of expiry of deposit. just in case a depositor wants his money earlier, he has to provides a notice to the bank which allows the withdrawal after charging a penal rate of interest from the depositor.

Thus, time deposits lack perfect liquidity and can't be included within the money supply. But this definition is more appropriate from the purpose of view of monetary policy because the central bank can exercise control over a wider area that has both demand and time deposits held by commercial banks.

Monetary and Fiscal Policies in India

Economic stabilization: Monetary Policy, fiscal policy and Direct Controls!

Economic stabilisation is one among the most remedies to effectively control or eliminate the periodic trade cycles which plague capitalist economy. Economic stabilisation, it should be noted, isn't merely confined to one individual sector of an economy but embraces all its facts. so as to ensure economic stability, variety of economic measures need to be devised and implemented.

In modem times, a programme of economic stabilisation is typically directed towards the attainment of three objectives: (i) controlling or moderating cyclical fluctuations; (ii) encouraging and sustaining economic growth at full employment level; and (iii) maintaining the value of money through price stabilisation. Thus, the goal of economic stability is often easily resolved into the dual objectives of sustained full employment and therefore the achievement of a degree of price stability.

The following instruments are wont to attain the objectives of economic stabilisation, particularly control of trade cycles, relative price stability and attainment of economic growth:

(1) Monetary policy

(2) Fiscal policy; and

(3) Direct controls

1. Monetary Policy:

The most commonly advocated policy of solving the matter of fluctuations is monetary policy. Monetary policy pertains to banking and credit, availability of loans to firms and households, interest rates, public debt and its management, and monetary management.

However, the basic problem of monetary policy in reference to trade cycles is to regulate and regulate the quantity of credit in such a way as to attain economic stability. During a depression, credit must be expanded and through an inflationary boom, its flow must be checked.

Monetary management is that the function of the commercial banking system, and thru it, its effects are primarily exerted the economy as an entire. Monetary management directly affects the volume of cash reserves of banks, regulates the availability of money and credit within the economy, thereby influencing the structure of interest rates and availability of credit.

Both these factors affect the components of aggregate demand (consumption plus investment) and therefore the flow of expenditures within the economy. it's obvious that an expansion in bank credit causes an increasing flow of expenditure (in terms of money) and contraction in bank credit reduces it.

In the armoury of the central bank, there are quantitative also as qualitative weapons to control the credit- creating activity of the banking system. they're bank rate, open market operations and reserve ratios. These are interrelated to tools which operate the reserves of member banks which influence the ability and willingness of the banks to expand credit. Selective credit controls are applied to control the extension of credit for particular purposes.

We shall now briefly discuss the implications of those weapons.

Bank Rate Policy:

Due to various reasons, the bank rate policy is comparatively an ineffective weapon of credit control. However, from the point of view of contra cyclical monetary policy, bank rate policy is typically interpreted as an evidence of monetary authority’s judgement regarding the contribution of the current flow of money and bank credit to general economic stability.

That is to mention, an increase in the bank rate indicates that the central bank considers that liquidity within the banking system possesses an inflationary potential. It implies that the flow of money and credit is very much in excess of the actual productive capacity of the economy and thus, a restraint on the expansion of money supply through dear money policy is desirable.

On the opposite hand, a reduction in the bank rate is usually interpreted as an evidence of a shift within the direction of monetary policy towards an inexpensive and expansive money policy. a reduction in bank rate then is more significant as an emblem of an easy money policy than anything. However, the bank rate is most effective as an instrument of restraint.

Effectiveness of bank rate Policy in Expansion:

According to Estey, the subsequent difficulties usually arise in the way of an efficient discount policy in expansion:

1. During high prosperity, the demand for credit by businessmen could also be interest-inelastic.

2. The rising of bank rate and a consequent rise within the market rates of interest may attract loan able funds from the financial intermediaries within the money market and assist in counteracting undesired effects.

3. Though the quantity of money is also controlled by the banking system, the velocity of its circulation isn't directly under the influence of banks. Banking policy may determine how much credit there should be but it's the trade which decides how much and the way fast it'll be used. Thus, if the velocity of the movement is contrary to the volume of credit, banking policy is rendered ineffective.

4. There's also the difficulty of proper timing within the application of banking policy. Brakes must be applied at the proper time and within the right quarter. If they're applied timely, they must bring expansion to an end with factors of production not fully employed. And when applied too late, there could be a runaway monetary expansion and inflation, completely out of control.

Open Market Operations:

The technique of open market operations refers to the purchase and sale of securities by the central bank. A selling operation reduces commercial banks’ reserves and their lending power.

However, because of the need to maintain the government securities market, the central bank is totally free to sell government securities when and in what amounts it wishes so as to influence commercial banks’ reserve position. Thus, when an outsized public debt is outstanding, by expanding the securities market, monetary policy and management of the public debt become inseparably intertwined.

Reserve Ratios:

The monetary authorities have at their disposal another best way of influencing reserves and activities of commercial banks which weapon may be a change in cash reserve ratios. Changes within the reserve ratios become effective at a pre-announced date.

Their immediate effect is to change the liquidity position in the banking system. When the cash reserve ratio is raised commercial banks find their existing level of cash reserves inadequate to hide deposits and need to raise funds by disposing liquid assets in the monetary market. The reverse is the case when the reserve ratio is lowered. Thus, changes within the reserve ratios can influence directly the cash volume and therefore the lending capacity of the banks.

It appears that the bank rate policy, open market operations and changes in reserve ratios exert their influence on the cost, volume and availability of bank reserves through reserves, on the money supply.

Selective Controls:

Selective controls or qualitative credit control is used to divert the flow of credit into and out of particular segments of the credit market. Selective controls aim at influencing the aim of borrowing. They regulate the extension of credit for particular purposes. The rationale for the use of selective controls is that credit may be deemed excessive in some sectors at a time when a general credit control would be contrary to the maintenance of economic stability.

It goes without saying that these various means of credit controls are to be co-ordinated to attain the goal of economic stability.

Effectiveness of Monetary Control:

Monetary policy is far more effective in curbing a boom than in helping to bring the economy out of a depression ary state. It’s long been recognised that monetary management can always contract the money supply sufficiently to finish any boom, but it's little capacity to finish a contraction.

This is because the actions of monetary management don't directly enter the income-expenditure stream because the best contra-cyclical weapon, for his or her first impact is on the asset structure of monetary institutions, and during this process of altering the assets’ structure, rate of interest, volume of credit and therefore the income-expenditure flow could also be altered.

All these operate more significantly in restraining the income stream during expansion than in inducing a rise during contraction. However, the best advantage of monetary policy is its flexibility. Monetary management makes decisions about the rate of change within the money supplies that are consistent with economic stability and growth on a judgement of given quantitative and qualitative evidences.

But, whether now of monetary policy will prove its effectiveness or not depends on its exact timing. Manipulation of bank rate and open market dealings by the central bank should be reasonably effective if applied quickly and continuously in preventing booms from developing and consequently, into a depression.

To sum up, monetary policy may be a necessary a part of the stabilisation programme but it alone isn't sufficient to attain the specified goal. Monetary policy, if used as a tool of economic stabilisation, in some ways, is a complement of fiscal policy.

It is strong, whereas fiscal policy is weak. it's flexible and capable of quick alternations to suit the measure of pressures of the time and wishes. However, it's to be co-ordinated with economic policy. A wrong monetary policy may seriously endanger and even destroy the effectiveness of fiscal policy. Thus, monetary policy and fiscal policy, each reinforcing and supplementing the opposite, are the essential elements in devising an economic stabilisation programme.

2. Fiscal Policy:

Today, foremost among the techniques of stabilisation is fiscal policy. fiscal policy as a tool of economic stability, however, has received its due importance under the influence of Keynesian economies only since Depression years of the 1930s.

The term ‘‘fiscal policy” embraces the tax and expenditure policies of the govt. Thus, fiscal policy operates through the control of state expenditures and tax receipts. It encompasses two separate but related decisions: public expenditures and level and structure of taxes. the quantity of public outlay, the inducement and effects of taxation and therefore the relation between expenditure and revenue exert a major impact upon the free enterprise economy.

Broadly speaking, the taxation policy of the govt relates to the programme of curbing private spending. The expenditure policy, on the opposite hand, deals with the channels by which government spending on new goods and services directly raise aggregate demand and indirectly income through the secondary spending which takes place on account of the multiplier effect.

Taxation, on the opposite hand, operates to scale back the level of personal spending (on both consumption and investment) by reducing the income and therefore the resulting savings within the community. Hence, under the budgetary phenomenon, public expenditure and revenue are often combined in various ways to realize the specified stimulating or deflationary effect on aggregate demand.

Thus, fiscal policy has quantitative also as qualitative aspect changes in tax rates, the structure of taxation and its incidence influence the volume and direction or private spending in economy. Similarly, changes in government’s expenditures and its structure of allocations also will have quantitative and redistributive effects on time, consumption and aggregate demand of the community.

As a matter of fact, all government spending is an inducement to extend the aggregate demand (both volume and components) and has an inflationary bias within the sense that it releases funds for the private economy which are then available to be used in trade and business.

Similarly, a discount in government spending features a deflationary bias and it reduces the aggregate demand (its volume and relative components during which the expenditure is curtailed). Thus, the composition of public expenditures and public revenue not only help to mould the economic structure of the country but also exert certain effects on the economy.

For maximum effectiveness, fiscal policy should be planned on both long-run and short-run basis. Long- run fiscal policy obviously cares with the long- run trends in government income and spending. Within the framework of such a long-range plan of fiscal operations, the budget is often made to vary cyclically so as to moderate the short-run economic fluctuations.

Basically, two sets of techniques are often employed for planning the specified flexibility within the relation between tax income and expenditure: (1) built-in flexibility or automatic stabilisers, and (2) discretionary action.

Built in Flexibility: The operation of a fiscal policy is usually confronted with the matter of timing and forecast. A fiscal policy administrator has always to face the question: When to do what? But it's a really difficult and complicated question to answer. Thus, so as to minimise the difficulties that arise from uncertainties of forecasting and timing of fiscal operations, an automatic stabiliser programme is usually advocated.

Automatic stabiliser programme implies that during a given framework of expenditure and revenue relation during a budgetary policy, there exist factors which give automatically corrective influences on movements in national income, employment, etc. this is often what's called built-in flexibility. It refers to a passive budgetary policy.

The essence of built-in flexibility is that (i) with a given set of tax rates tax yields will vary directly with national income, and (ii) there are certain lines of government expenditures which tend to vary inversely with movements in national income.

Thus, when the national income rises, the present structure of taxes and expenditures tend to automatically increase public revenue relative to expenditure, and to increase expenditures relative to revenue when the value falls. These changes tend to mitigate or offset inflation or depression a minimum of partially. Thus, a progressive tax structure seems to be the simplest automatic stabiliser.

Likewise, certain sorts of government expenditure schemes like unemployment compensation programmes, government subsidies or price-support programmes also offset changes in income by varying inversely with movements in national income.

However, automatic stabilisers aren't a panacea for economic fluctuations, since they operate only as a partial offset to changes in national income, but provide a force to reverse the direction of the change within the income.

They slow down the rate of decline in aggregate income but contain no provision for restoring income to its former level. Thus, they ought to be recognised as a really useful device of fiscal operations but not the sole device. Simultaneously, there should be scope for discretionary policies because the circumstances will involve.

Discretionary Action:

Quite often, it becomes absolutely necessary to possess fiscal operations with a tool kit of discretionary policies consisting of measures for putting into effect with a minimum delay, the changes in government expenditures. This calls for a skeleton of structure projects providing for administrative discretion to use them and therefore the funds to place them into effect.

It calls for a budgetary manipulation an active budget policy constituting flexible tax rates and expenditures. There are often 3 ways of discretionary changes in tax rates and expenditures: changing expenditure with constant tax rates; changing tax rates and constant expenditure; and a mixture of changing tax rates and changing expenditures.

In general, the primary method is perhaps superior to the second during a depression. that's to mention, to increase expenditures with the level of taxes remaining unchanged is beneficial in pushing up the aggregate spending and effective demand within the economy. However, the second method will convince be superior to the primary during inflation.

That is to mention, inflation might be checked effectively by increasing the tax rates with a given expenditure programme. But it's easy to ascertain that the third method is far simpler during inflation also as deflation than the opposite two.

Inflation would, of course, be more effectively curbed when taxes are enhanced and public expenditure is additionally simultaneously reduced. Similarly, during a depression, the spending rate of personal economy are going to be quickly lifted up if taxes are reduced simultaneously with the increasing public expenditure.

However, the most difficulty with most discretionary policies is their proper timing. Delay in discretion and implementation will aggravate the problem and therefore the programme might not prove to be effective in solving the issues.

Thus, many economists fear that discretionary government actions are likely to do more harm than good, due to the uncertainty of government actions and therefore the political pressures to favour vested interests. that's why reliance on built-in stabilisers, as far as possible, has been advocated.

Public finance

Meaning, nature and scope of Public Finance

Subject matter of public finance:

The economics of public finance is fundamentally concerned with the technique of rising and dispersion of dollars for the functioning of the government. Thus, the find out about of public revenue and public expenditure constitutes the principal division in the find out about of public finance.

But with these two symmetrical branches of public finance, the hassle of business enterprise of elevating and disbursing of assets additionally arises.

It has also to resolve the query of what is to be performed in case public expenditure exceeds the revenues of the state. In solving the first problem, “financial administration” Comes into the picture. In the latter problem, obviously, the technique of public borrowings or the mechanism of public debt is to be studied.

Since both public debt as well as financial administration offers upward jab to a variety of distinctive problems, these are conventionally handled as a separate branch of the subject.

As such, we have four major divisions (traditionally set) in the find out about of public finance:

2. Public expenditure, which offers with the ideas and problems bearing on to the allocation of public spending. Here we find out about the vital concepts governing the glide of public dollars into exclusive channels; classification and justification of public expenditure; expenditure insurance policies of the authorities and the measures adopted for accepted welfare.

3. Public debt, which offers with the study of the motives and strategies of public loans as nicely as public debt management.

4. Financial administration, under this the trouble of how the financial equipment is organised and administered is dealt with.

The scope of public finance

The scope of public finance is not just to find out about the composition of public income and public expenditure. It covers a full discussion of the have an impact on of government fiscal operations on the stage of typical activity, employment, costs and increase system of the financial device as a whole.

According to Musgrave, the scope of public finance embraces the following three functions of the government’s budgetary coverage limited to the fiscal department:

(i) the allocation branch,

(ii) the distribution branch, and

(iii) the stabilisation branch.

These refer to three goals of finances policy, i.e., the use of fiscal instruments:

(i) to impenetrable adjustments in the allocation of resources,

(ii) to impenetrable changes in the distribution of income and wealth, and

(iii) to achieve financial stabilisation.

Thus, the function of the allocation department of the fiscal branch is to decide what changes in allocation are needed, who shall endure the cost, what income and expenditure policies to be formulated to fulfil the desired objectives.

The characteristic of the distribution department is to decide what steps are needed to carry about the favoured or equitable nation of distribution in the economy and the stabilisation branch shall confine itself to the choices as to what ought to be carried out to tightly closed charge steadiness and to keep full employment level.

Further, modern public finance has two aspects:

(i) positive aspect and

(ii) normative aspect.

In its advantageous aspect, the study of public finance is concerned with what are sources of public revenue, gadgets of public expenditure, constituents of budget, and formal as nicely as tremendous incidence of the fiscal operations.

In its normative aspect, norms or standards of the government’s monetary operations are laid down, investigated, and appraised. The simple norm of modern finance is normal economic welfare. On normative consideration, public finance turns into a skilful art, whereas in its nice aspect, it remains a fiscal science.

Key Takeaways:

(i) Primary functions (ii) Secondary function (iii) Contingent functions.

3. The demand for money arises from two important functions of money.

4. The primary is that money acts as a medium of exchange and therefore the second is that it's a store of value.

5. Keynes in his General Theory used a replacement term “liquidity preference” for the demand for money:

6. The transactions demand for money arises from the medium of exchange function of money in making regular payments for goods and services.

7. The Precautionary motive relates to “the desire to produce for contingencies requiring sudden expenditures and for unforeseen opportunities of advantageous purchases.”

8. The speculative (or asset or liquidity preference) demand for money is for securing profit from knowing better than the market what the longer term will bring forth”.

9. The supply of money is a stock at a specific point of time, though it conveys the idea of a flow over time

10. The term ‘‘fiscal policy” embraces the tax and expenditure policies of the govt. Thus, fiscal policy operates through the control of state expenditures and tax receipts.

What is welfare economics?

Welfare economics is a study of how the allocation of resources and goods affects social welfare. This is directly related to the study of economic efficiency and income distribution, and how these two factors affect the overall well-being of people in the economy. In fact, welfare economists seek to provide tools to guide public policy to achieve social and economic outcomes that are beneficial to society as a whole. However, welfare economics is a subjective study that relies heavily on selected assumptions regarding how the welfare of individuals and society as a whole can be defined, measured and compared.

Understanding welfare economics

Welfare economics begins with the application of utility theory in microeconomics. Utility refers to the perceived value associated with a particular product or service. In mainstream microeconomic theory, individuals seek to maximize utility through behavioral and consumption choices, and the interaction of buyers and sellers with the laws of supply and demand in competitive markets creates consumer and producer surplus.

A microeconomic comparison of consumer and producer surplus in markets under different market structures and conditions constitutes a basic version of welfare economics. The simplest version of welfare economics is "Which market structure and allocation of economic resources across individuals and production processes maximizes the total utility received by all individuals, or consumers and production across all markets. Do you want to maximize the total surplus of the person? " ?? Welfare economics seeks economic conditions that produce the highest levels of social satisfaction among its members.