Unit - 6

International Trade

Introduction:

The drawbacks of the classical theory of international trade induced the Swedish economist Prof. Heckscher (1919) to develop an alternate explanation of comparative advantage theory. His theory was further improved by his pupil Bertil Ohlin (1933). Hence it is known as Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) theory.

Hecksher-Ohlin (H-O) theory argues that there is no need for a separate theory to explain international trade. According to it, international trade is but a special case of interregional trade. Factor immobility which was the base for a separate explanation of international trade by classical economists, does not hold true as factors are mobile or immobile even between two regions of the same country and also between the two countries. It is difference in degree rather than in nature.

The Modern or Hecksher-Ohlin (H-O) Theory explains the new approach to comparative advantage on the basis of general value theory. From all the forces that work together in general equilibrium, H-O theory isolates the differences in physical availability or supply of factors of production among the nations to explain the difference in relative commodity prices and trade between the countries. According to this theory “a nation will export the commodity whose production requires the intensive use of the nation’s relatively abundant and cheap factor and import the commodity whose production requires the intensive use of the nation’s relatively scarce and expensive factor”.

H-O theory explains the modern approach to international theory on the basis of the following assumptions:

On the basis of the above assumptions, it can be stated that (i) each commodity differs in factor intensity (ii) each country differs in factor endowments leading to differences in factor prices. It is therefore necessary to understand the above terms factors intensity and factor abundance in order to explain H-O theory.

(A) Factor Intensity

In our two-country commodity model, commodity Y is capital intensive if the capital-labour ratio (K/L) in the production of Y is greater than K/L used in the proportion of X. To explain with an example, if commodity Y requires 2 units of capital (2K) and 2 units of labour (2L), the capital-labour ratio (K/L) for producing commodity Y is 2/2 = 1. For commodity X, if the required inputs are 1K and 4L, the capital-labour (K/L) ratio ¼.

The ratios can be stated as:

For commodity Y, the K/L = 2K /2L = 1

For commodity X, the K/L = 1K/4L =1/4

Here commodity Y is capital intensive and X is labour intensive

Commodity | Capital | Labour | K/L Ratio |

Y X | 2 3 | 2 12 | 1 1/4 |

Capital or labour intensity is not measured in absolute terms but by the ratio i.e., units of capital per labour or units of labour per capital. In our example, K/L ratio for Y is 1 and for X is ¼.

Instead, if units of capital and labour used in the production of Y are 2K and 2L whereas for X, 3K and 12L, commodity Y still remains capital intensive through X requires more capital in absolute terms i.e., 3K. capital used per labour in the production of X is 3K/2L i.e., 3/12 = ¼. Whereas for Y it is 2K/2L = 1 as shown in table.

Commodity | Capital | Labour | K/L Ratio |

Y X | 2 3 | 2 12 | 1 1/4 |

Factor intensity, therefore is measured by the factor ratios and not by absolute units.

In our example of two commodities, two factors and two countries, we say commodity Y is capital intensive if capital-labour ratio (K/L) of Y is greater than the K/L ratio of X. to illustrate the point let us say that production of one unit of Y requires two units of capital (2K) and 2-unit labour (2L). the capital-labour ratio (K/L) of Y is2/2 =1. Similarly, if the production of X requires 3K and 12L, the capital-labour ratio of X is ¼. Here we say Y is capital intensive and X is labour intensive.

It is to be noted that goods are not be noted categorized based on absolute quantity or units of capital and labour used in the production of a unit of good Y or X but the ratio of capital-labour of each c6K and 24L, here good X requires more capital in absolute number than Y. Yet in terms of ratio, it is Y which is capital intensive (5/5 =1) whereas X is labour intensive (6/24 = ¼).

(B) Factor Abundance

Factor Abundance in Physical Terms

Nations differ in factor endowments. Some have more natural resources, some have more of labour and others more of capital. A given county’s factor abundance can be defined either in physical terms or in terms of relative factor prices. In our two-country model, country I is capital abundant, if in physical terms the ratio of total amount of capital (TK) to the total amount of labour (TL) that is (TK/TL) in nation 1 is greater than nation 2 i.e.,  >

> . It should be noted that it is not the absolute amount of capital and labour but the ratio of the total amount of capital to the total amount of labour. Country 1 may have a lesser quantity of capital than country 2, yet country 1 will be capital abundant if TK to TL in country 1 is greater than in country 2.

. It should be noted that it is not the absolute amount of capital and labour but the ratio of the total amount of capital to the total amount of labour. Country 1 may have a lesser quantity of capital than country 2, yet country 1 will be capital abundant if TK to TL in country 1 is greater than in country 2.

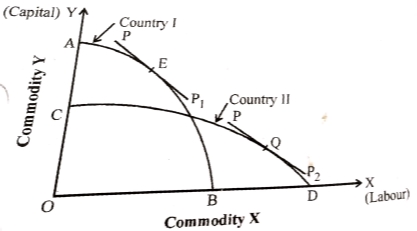

Factor abundance in physical terms can also be explained with the help of production possibility curve OR production frontier, as shown in fig.

In the diagram below, country I is capital abundant, therefore, its production possibility curve is skewed towards Y-axis. Country II is labour abundant, accordingly its production possibility curve is skewed towards X-axis.

Country I can produce OA of Y i.e., CA quantity more than country II. Similarly, country II can produce OD of X, i.e., BD quantity more than country I. country II can produce more of X which is labour intensive because it is capital intensive due to its abundant capital.

The domestic price lines are PP1 and PP2 in countries I and II. The points E and Q are the respective equilibrium points of production and consumption. The price lines P1 and P2 indicate that commodity Y is cheaper in country I and X in country II, providing the basis for trade.

Factor Abundance in Terms of Factor Price

The cause of international trade is the difference in commodity prices. Price of commodity differs because of cost of production which in turn depends on factor prices. It is therefore necessary to explain factor abundance theory in terms of factor prices.

A nation is capital abundant if the ratio of the capital price to the labour price (PK/PL) is lower in it than in the other.

It can be stated as:

<

<

The two definitions give us the same meaning. The physical abundance explains the supply side. The price ratios are based on the price of factors determined by the demand for and supply of factors. The demand for factors derived demand i.e., derived from the demand for commodities produced with the help of factors. In our two nations model, demand is assumed to be the same in both the nations. In a country where the supply of physical units of capital (K) is more, its price has to be lower in comparison to the other factor(L). If in nation 1, the price of capital i.e., interest (r) is less than the price of labour i.e., wage (w) and in nation 2, r is more than w, then we have  . Here nation 1 is a capital abundant country.

. Here nation 1 is a capital abundant country.

From our above analysis we can derive the following conclusions:

Key Takeaways

In the early 1950s, Russian-born American economist Wassily W. Leontief closely studied the American economy and noted that the United States was abundant in capital and, therefore, should export goods intensive. However, his research using real data showed the opposite: the United States imported more capital-intensive goods. In 1953, Wassily Leontief published the results of experiential surveys mainly renowned in economics, attempt to test the reliability of the HO model with U.S. commercial models. According to the theory of factor proportions, the United States should have imported labor-intensive goods, but instead, it was effectively exporting them, and its analysis became known as the Leontief paradox because that this was the reverse of what was expected by factor proportion theory. This econometric research is the result of Wassily W. Leontief's attempt to empirically test the Heckscher-Ohlin theory ("HO theory"). measured that a country will be required to export the products which intensively use its many factors of manufacture and to import those which intensively use its inadequate issue.

Leontief's objectives were: to prove that the H-O model was correct; and to show that US exports were capital intensive. Leontief developed an input-output table for the United States in 1947 to establish the capital-labor ratios used in the production of American exports and imports. In one of the most widely discussed tests of factor proportion theory, Leontief attempted to expose the structure of the relative factor proportions of the United States' contribution to international trade. He found that U.S. exports used a capital-labor ratio of $ 13,991 per man-year, while import substitutes used a ratio of $ 18,184 per man-year. In the following years, economists historically noted at this time that labor in the United States was available in constant and more productive quantities than in many other countries; it therefore made sense to export labor-intensive goods. Over the decades, many economists have used theories and data to explain and downplay the impact of the paradox. The general consensus is that the United States is the only country that is most abundantly capable of capital. Therefore, one would expect the United States to export complete assets and import labor-intensive goods.

Assumption

The argument of the Leontief paradox has barely been competent to ascertain firm conclusions. It has provided a good deal of imminent into the international trade situation of the U.S., but it has almost not helped to ascertain or disprove the H.O. theory of global trade.

Some economists pointed out that Leontief ignored worker’s proficiency and this could be seen as a key justification if we regard that human capital is the US’s comparatively profuse issue.

The Leontief Paradox evoked a prevalent reaction from academicians. Several attempts were made by them to either protect the paradox or determine its rational flaws and verify it wrong.

Leontief recognized that allowing for only labor and capital as inputs of a nation is impractical and therefore, he highlighted a country’s endowment of natural resources as a critical component in production.

Re-estimation of factor-intensity of the US exports and imports by incorporating one or more of the additional factors has been found to yield varying results, from underneath Leontief Paradox to contradicting it or weakening it.

Key Takeaways:

What is trade?

Trade is the fundamental state of business activity it includes sale and purchase of the goods or services.it involves the exchange or transfer of goods or services. The producers build the goods, then it transfers to the whole seller, then to a retailer and finally reached to the consumer.

Types of trade:

The most widely used concept of the terms of trade is what has been caned the net barker terms of trade which refers to the relation between prices of exports and prices of imports. In symbolic terms:

Tc = Px/Pm

Where,

Tc stands for net barter terms of trade.

Px stands for price of exports (x),

Pm stands for price of imports (m).

When we want to understand the changes in net barter tends of trade over a period of time, we prepare the price index numbers of exports and imports by choosing a particular appropriate base year and acquire the subsequent ratio:

Px1/ Pm1: Px0/ Pm0

Px„ Pm„

where Px0 and Pm0 represent price index numbers of exports and imports within the base year respectively, and Px1 and Pm1 denote price level numbers of exports and imports respectively within the current year.

Since the costs of both exports and imports within the base year are taken as 100, the terms of trade in the base year would be adequate to one

Px0/ Pm0 = 100/100 = 1

Suppose within the current period the price index number of exports has gone up to 165, and therefore the price index number of imports has risen to 110, then terms of trade in the current period would be:

165/110: 100/100 = 1.5:1

Thus, within the current period, terms of trade have improved by 50 pa’ cent as compared to the base period. Further, it implies that if the prices of exports of a country rise relatively greater than those of its imports, terms of trade for it might improve or become favourable.

On the opposite hand, if the prices of imports rise relatively greater than those of its exports, terms of trade for it might deteriorate or become unfavourable. Thus, net barter terms of trade are a crucial concept which may be applied to measure changes within the capacity of exports of a country to buy the imported products. Obviously, if internet barter terms of trade of a country improve over a period of your time, it can purchase more quantity of imported products for a given volume of its exports.

But the concept of net barter terms of trade suffers from some important limitations therein it shows nothing about the changes within the volume of trade. If the prices of exports rise relatively to those of its imports but because of this rise in prices, the quantity of exports falls substantially, then the gain from rise in export prices could also be offset or maybe more than offset by the decline in exports.

This has been well described by saying, “We make an enormous profit on every sale but we don’t sell much”. so as to overcome this drawback, the net barter terms of trade are weighted by the quantity of exports. This has led to the development of another concept of terms of trade referred to as the income terms of trade which shall be explained later. Even so, internet barter terms of trade are most generally used concept to measure the power of the exports of a country to buy imports.

This concept of the gross terms of trade was introduced by F.W. Taussig and in his view this is often an improvement over the concept of net barter terms of trade because it directly takes into account the volume of trade. Accordingly, the gross barter terms of trade ask the relation of the volume of imports to the volume of exports. Thus,

Tg = Qm/Qx

Where

Tg = gross barter terms of trade,

Qm = quantity of imports

Qx = quantity of exports

To compare the change within the trade situation over a period of your time, the subsequent ratio is employed

Qm1/Qx1: Qm0/Qx0

Where the subscript 0 denotes the base year and therefore the subscript I denotes the current year.

It is obvious that the gross barter terms of trade for a country will rise (i.e., will improve) if more imports may be obtained for a given volume of exports. it's important to notice that when the balance of trade is in equilibrium (that is, when value of exports is adequate to the value of imports), the gross barter terms of trade amount to an equivalent thing as net barter terms of trade.

This can be shown as under:

Value of imports = price of imports x quantity of imports = Pm. Qm

Value of exports = Price of exports x quantity of exports = Px. Qx

Therefore, THE balance of trade is in equilibrium.

Px. Qx = Pm. Qm

Px. Qm = Pm Qx

However, when balance of trade is not its equilibrium, the gross barter terms of trade would differ from net barter terms of trade.

Gross barter terms of trade include all the items in the balance of payments thus making its wider and comprehensive than net terms of trade. The gross barter terms of trade differ from the net barter terms of trade as the former include unilateral transfers.

LIMITATIONS

Taussig's concept of gross barter terms of trade has been criticised on the grounds

(a) It expresses the terms of trade in terms of quantity instead of prices. For analytical as well as practical purposes terms of trade expressed in value or price are more relevant.

(b) It includes payments such as unilateral payments which do not depend on trade but on factors mostly unrelated to the trade.

(c) Gross barter terms of trade explain the changes in balance of trade/payments rather than the changes in export-import prices.

(d) A favourable GBTT need not necessarily indicate higher welfare as welfare depends on many factors other than more imports that is favourable GBTT.

In order to enhance upon the net barter terms of trade G.S. Dorrance developed the concept of income terms of trade which is obtained by weighting net barter terms of trade by the volume of exports. Income terms of trade therefore ask the index of the value of exports divided by the price of imports. Symbolically, income terms of trade are often written as

Ty = Px. Qx/Pm

Where

Ty = Income terms of trade

Px = Price of exports

Qx = Volume of exports

Pm= Price of imports

Income terms of trade yields a higher index of the capacity to import of a country and is, indeed, sometimes called ‘capacity to import. this is often because in the long run balance of payments must be in equilibrium the value of exports would be adequate to the value of imports.

Thus, in the long run:

Pm, Qm = Px, Qx

Qm = Px. Qx/Pm

It follows from above that the volume of imports (Qm) which a country can purchase (that is, capacity to import) depends upon the income terms of trade i.e., Px. Qx/Pm. Since income terms of trade may be a better indicator of the capacity to import and since the developing countries are unable to vary Px and Pm. Kindleberger’ thinks it to be superior to the net barter terms of trade for these countries, However, it may be mentioned once more that it's the concept of net barter terms of trade that's usually employed.

The changes in income terms of trade depend on price and volume of exports. An improvement in income terms of trade tells us the increased capacity to import, hence some economist considers it as a better explanation of gains of trade. Other things being equal the capacity to import increases when (i) export prices increase

LIMITATIONS

i) The income terms of trade, however, do not measure precisely the gain or loss from the trade. More imports may be at the cost of higher exports which involve larger amount of domestic resources which could have been used for domestic consumption.

ii) Increase in exports may be due to a decline in prices. With import prices remaining the same, the capacity of the country to import increases. It is, however, possible that additional income is due to increase in exports at a lower price. This situation, however makes commodity terms of trade deteriorate.

iii) Income terms of trade takes into account the import capacity of a country based on export receipts only but neglects foreign exchange receipts from other sources. It is argued that a country s capacity to import does not depend only on export receipts but on total foreign exchange receipts.

(iv) The concept of income terms of trade fails to consider the welfare aspects of trade. More exports involve more resources to produce those goods. These resources could have been used to produce goods for domestic consumption which have increased the economic welfare of the people.

To overcome the limitations of commodity terms of trade, Prof. Viner developed the concept of single factoral terms of trade. This concept admits changes in productivity of factors involved in producing exports. The single factoral terms of trade can be expressed as

Ts = (Px/Pm) Zx

where, Ts = Single factoral terms of trade

Px/Pm= Commodity terms of trade (Tc)

Zx= Productivity index of the export sector

Thus, the single factoral terms of trade (Ts) measures the amount of imports the nation gets per unit of domestic factors of production embodied in its exports.

For example, if Tc= 95/110 and the productivity in our export sector rose from 100 in 2015 to 125 in 2019, then our single factoral terms of trade will be

Ts = (95/110) 125 = (0.8636) 125 =107.95

Here the exporting country received 7.95 percent more imports per unit of domestic factors embodied in its exports than what it received in 2015.

LIMITATIONS

i) It is difficult to obtain data to construct a productivity index.

ii) It does not consider the production cost of imports in the import goods producing country.

iii) Comparison between periods becomes impractical as composition of exports and imports may change.

iv) A favourable single factoral terms of trade may lead to a decline in export prices turning Tc of the country unfavourable.

To eliminate the drawbacks associated with single factoral terms of trade, Jacob Viner worked out double factoral terms of trade. It can be expressed as:

TD= (Px/Pm) (Zx/Zm) x 100

where, TD= Double factoral terms of trade

Px/ Pm=Tc = Commodity terms of trade

Zx = Export productivity index

Zm=Import productivity index

TD explains the number of units of domestic factors embodied in our exports which are exchanged for a unit of foreign factors embodied in our imports. In other words, it takes into account Improvement in productivity of factors embodied both in export and import goods.

For example,

TD = (95/ 110) (130 / 105) x 100

= (0.8636) (1.2381) x 100=106.92

In this case, the double factoral terms of trade are in favour of their exporting country as its productive efficiency of the factors involved in exports has increased relatively to that of the factors embodied in the imports. In other words, we receive more units of factors of production for a given unit embodied in our exports.

LIMITATION:

i) It is highly difficult to construct the productivity index.

ii) It involves comparison of changes in efficiency in productivity in export and import countries, which is impractical as socio economic and political conditions differ.

iii) Changes in productivity is less important for trading countries than the price and quantity involved in trade.

(iv) Prof. Kindleberger criticised this concept by stating that the exporting country is interested in its gain rather than the improvement in productivity in importing country.

Of all types of terms of trade, only net barter terms of trade, income terms of trade and single factoral terms of trade are made use of for practical purposes. Even from these, it is the net barter terms of trade which are used for all official purposes while measuring terms of trade and changes therein.

Terms of trade of a country are favourable or not, depend on a number of factors. The important of them are:

1. Changes in Factor Endowments: Availability of factors of production in a country may increase or decrease over a period of time. An increase may enable a country to export more and a decrease may lead to increase in imports resulting in changes in terms of trade.

2. Reciprocal Demand: The intensity of demand for other country's goods changes the terms of trade. If India's demand for goods from China is strong and increasing compared to China's demand for Indian goods, then the terms of trade will be adverse to India.

3. Improvement in Technology: It may lead to reduction in cost of production, requirement of raw materials and other associated changes which may improve the terms of trade. i Developing countries which export raw materials may experience a deterioration in terms of trade due to decline in demand as a result of such changes.

4. Changes in Tastes: Demand for goods may increase or decrease whenever tastes change. Change in taste may include changes in fashion and habits. For example, a change in taste for tea and coffee may affect the terms of trade of those countries which export these items. Declining habit of smoking throughout world may affect the terms of trade of tobacco exporting countries.

5. Tariffs: A country imposes tariffs on its imports to influence its terms of trade in its favour as imports may decline or prices of imports may be reduced by the countries who export these goods.

6. Economic Development: In the process of development an economy experiences dynamic changes leading to the changes in composition and direction of its trade. Besides, changes in quality of inputs, technology and work culture may lead to changes in terms of trade. Some of the developing countries specially emerging market economies are experiencing these changes resulting in positive changes in their terms of trade.

7. Nature of Commodities: The nature and type of goods traded differ from country to country. Developed countries exports mainly comprise capital goods and manufactures. They have a strong demand from the developing countries. Higher cost of production combined with less elastic demand result in high prices for these goods. The developing and poor countries, specially whose exports are mainly primary goods (with some exceptions like crude oil) command less price. The main reasons may be low cost and elastic demand for primary goods. Therefore, it is argued that the developing countries suffer from adverse terms of trade.

A trade barrier is any obstacle that limits the movement of trade flows between countries. Generally, the purpose of this measure is to protect the domestic economy.

No country however rich or large can make everything it needs or has all the resources it requires for its manufacturing industries. Yet, some countries are against free trade. They believe that free trade is bad for their economies and hurts growth and employment. So, what are the arguments used to impose trade barriers?

There are four types of trade barriers that can be implemented by countries. They are Voluntary Export Restraints, Regulatory Barriers, Anti-Dumping Duties, and Subsidies.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is the only global international organization dealing with the rules of trade between nations. At its heart are the WTO agreements, negotiated and signed by the bulk of the world’s trading nations and ratified in their parliaments. The goal is to ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably and freely as possible.

Objectives of WTO

Key Takeaway:

as possible.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) can be defined as: When an investor buys a company at the border of the landlord's country, far away from his home country. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), if a foreign investor owns more than 10% of a local company, this means that the foreign investor controls the local company.

One other explanation basically suggests that a company in one country is investing heavily to build a factory in another country.

Foreign direct investment plays an important role in global entrepreneurs and businesses. FDI makes it easy for businesses to provide new business environments and markets, cheaper production equipment, access to the latest technology, and cheaper financing and skills.

There are three main benefits of inward FDI for a host country: the resource-transfer effect, the employment effect, and the balance of payments effect.

2. Employment Effects: The beneficial employment effect claimed for FDI is that it brings jobs to the host countries that would otherwise not be created there. Direct effects arise when a foreign MNE directly employs host country’s citizen.

3. Balance of Payment: The effect FDI has on a country’s balance of payment accounts is an important policy issue for most host countries. A country’s balance of payment accounts keeps track of both its payment to and its receipt from other countries. Governments normally are concerned when their country is running a deficit on the current account of their balance of payments. The current account tracks the export and imports of goods and services. A current account deficit, or trade deficit as it is often called, arises when a country is importing more goods and services than it is exporting. Governments typically prefer to see a current account surplus than a deficit. The only way in which a current account deficit can be supported in the long run is by selling assets to foreigners. For instance, the persistent US current account deficit of the 1980s and 1990s was financed by a steady sale of US assets (stocks, bonds, real estate, and the whole corporations) to foreigners. Because national governments dislike seeing the assets of their country fall into foreign hands, they prefer a current account surplus. FDI can help a country achieve this goal in two ways.

4. FDI is a substitute for imports of goods and services, it improves the current account of the host’s countries/balance of payments. Much of the FDI by Japanese automobile companies in the US and UK, for instance, substitutes for imports from Japan. Thus, the current account of the US balance of payments has improved somewhat because many Japanese companies are now supplying the US market from production facilities in the US, as opposed deficit in Japan. For insomuch as this has reduced the need to finance a current account deficit by asset sales to foreigners, the US has benefited.

5. Potential benefit arises when the MNE uses a foreign subsidiary to export goods and services to other countries.

Key Takeaway:

References:

1. “Modern Micro Economics”, Koutsoyiannis.

2. “Fundamentals of Engineering Economics”, Park, Prentice Hall.

3. “Economics”, Samuelson.

4. “Growth Economics”, Sen A.K, Penguin Books, England.