Unit-4

Analysis of Annuity

4.1.1 What Is an Annuity

An annuity is a financial product that provides a fixed stream of payments to a person, and it is mainly used by retirees as a source of income. Annuities are contracts that financial institutions grant and distribute (or sell) to invest funds from individuals. They assist people in dealing with the possibility of outliving their savings. The holding institution would release a stream of payments at a later date after annuitization.

The accumulation process refers to the period between when an annuity is purchased and when payouts begin. The contract enters the annuitization process once payments begin.

4.1.2 Understanding Annuity

Annuities were created to provide a stable source of consistent cash flow for people in their retirement years, as well as to ease concerns about outliving one's assets.

Annuities may also be used to convert a large lump sum payment into a regular stream of income, such as for lottery winners or those who have won a large cash payout in a case.

Lifetime fixed annuities, such as defined benefit benefits and Social Security, provide retirees with a stable cash flow before they pass away.

4.1.3 Annuity Types

Annuities may be formulated based on a variety of facts and considerations, such as the length of time over which annuity payments are guaranteed to continue. Annuities may be designed such that payments continue after annuitization for as long as the annuitant or their spouse (if a survivorship benefit is selected) is alive. Annuities may also be set up to pay out money for a set period of time, such as 20 years, regardless of how long the annuitant lives.

Annuities can start right away if a lump sum is deposited, or they can be arranged as deferred benefits. The immediate payment annuity is an example of this form of annuity, in which payments begin immediately.

Deferred income annuities are the opposite of an immediate annuity because they don't begin paying out after the initial investment. Instead, the client specifies an age at which they would like to begin receiving payments from the insurance company.

4.1.4 Fixed and Variable Annuities

Set or variable annuities are the most common types of annuities. Fixed annuities pay the annuitant in monthly instalments. Variable annuities allow the owner to earn higher future cash flows if the annuity fund's investments perform well, and lower payments if the fund's investments perform poorly. This offers less consistent cash flow than a fixed annuity, but it allows the annuitant to benefit from the fund's investment returns.

Although variable annuities are subject to market risk and the risk of losing money, riders and features may be applied to annuity contracts (usually at a cost) to make them work as hybrid fixed-variable annuities. Contract owners will profit from the portfolio's upside potential while still being protected by a lifetime minimum withdrawal benefit if the portfolio's value falls. Other riders may be added to the arrangement to provide a death benefit or accelerate payouts if the annuity holder is diagnosed with a terminal illness. Another common rider is the cost of living rider, which adjusts annual base cash flows for inflation based on adjustments in the CPI.

4.1.5 Illiquid Nature of Annuities

Annuities have been criticised for being illiquid. Annuity deposits are usually locked up for a period of time known as the surrender period, during which the annuitant may be penalised if any or part of the money is touched.

Depending on the commodity, these surrender periods will last anywhere from two to more than ten years. Surrender penalties may be as high as 10% or more at first, but the penalty usually decreases year after year as the surrender period progresses.

4.1.6 Annuities vs. Life Insurance

The two main categories of financial institutions that sell annuity plans are life insurance firms and investment companies. Annuities are a natural hedge for life insurance firms' insurance policies. Life insurance is purchased to protect against mortality risk, or the possibility of dying prematurely. Policyholders pay an annual fee to the insurance provider, which then pays out a lump sum when the policyholder dies.

The insurer will pay out the death insurance at a net loss if the policyholder dies early. These insurance firms use actuarial science and claims expertise to price their plans so that on average, policyholders can survive long enough for the insurer to make a profit.

Longevity risk, or the risk of outliving one's properties, is addressed by annuities. The issuer of the annuity faces the possibility that annuity holders will outlive their initial investment. Annuity issuers can mitigate mortality risk by selling annuities to consumers who are more likely to die young.

4.1.7 Cash Value in Annuities

In many cases, the cash value of permanent life insurance policies can be exchanged for an annuity product via a 1035 exchange with no tax consequences.

Agents and brokers offering annuities must have a state-issued life insurance licence and, in the case of variable annuities, a securities licence. The fee paid to these agents or brokers is usually based on the notional value of the annuity contract.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) oversee annuity products (FINRA).

4.1.8 Who Buys Annuities?

Annuities are good investment products for people who want a steady, assured retirement income. Because the lump sum invested in the annuity is illiquid and subject to withdrawal penalties, this financial product is not recommended for younger people or those who require liquidity.

Longevity risk is mitigated by the fact that annuity holders cannot outlive their income stream. The commodity is sufficient as long as the buyer knows that they are exchanging a liquid lump sum for a guaranteed sequence of cash flows. Some buyers wish to cash out an annuity at a profit in the future, but this is not the product's intended use.

People of any age who have earned a large lump sum of money and would like to exchange it for future cash flows also buy immediate annuities. The lottery winner's curse is that many lottery winners who receive a lump sum windfall frequently lose it all in a short period of time.

4.1.9 Surrender Period:

The surrender period is the time during which an investor is unable to withdraw funds from an annuity without incurring a surrender charge or fee. If the invested sum is removed before the end of this term, it will be subject to a substantial penalty. Investors should think about their financial needs for the length of that time span. For example, if a big event, such as a wedding, necessitates large sums of money, it might be prudent to consider whether the investor can afford to make the required annuity payments.

4.1.10 Income Rider:

After the annuity kicks in, the income rider guarantees that you can earn a fixed income. When considering income riders, investors should ask themselves two questions. First, when do they need the income? Payment terms and interest rates can differ depending on the length of the annuity. Second, how much is the income rider going to cost you? Although some organisations have the income rider for free, the majority of them charge a fee for this service.

4.1.11 Example of an Annuity:

A life insurance policy is an example of a fixed annuity, in which a person pays a set amount per month for a set period of time (typically 59.5 years) and earns a set income stream during their retirement years.

An immediate annuity is one in which a person pays a single premium to an insurance provider, say $200,000, and then collects monthly payments, say $5,000, for a set period of time. The size of an immediate annuity payment is determined by market conditions and interest rates.

4.1.12 The Bottom Line:

Annuities may be a good part of a retirement package, but they're still complicated financial instruments. Most companies do not offer them as part of an employee's retirement portfolio due to their sophistication.

However, President Donald Trump signed the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act into law in late December 2019, loosening the rules on how employers can choose annuity providers and provide annuity options in 401(k) and 403(b) investment plans. The relaxation of these rules may result in more annuity options being available to eligible workers in the near future.

Loans have become an important part of everyone's lives today, as they assist us in achieving some of our most important life goals. Loans play an important role in our lives, whether it's for purchasing a car, a home, or funding our children's education abroad.

However, when it comes to loans, the most critical term to remember is EMI. EMI stands for equated monthly instalment and refers to the monthly payments we make on a loan we chose. “EMI payments include both principal and interest payments on the loan amount. In the beginning, the interest part accounts for the majority of the EMI charge. The portion of interest repayment decreases as the loan term progresses, while contributions to principal repayment increase,” says Nitin Vyakaranam, founder and CEO of arthayantra.com, a leading online financial planning company.

4.2.1 Loan Amortization Schedule:

The loan amortisation plan is a table that shows the loan balance as well as the EMI bill. It depicts the relationship between the interest and principal components of an EMI payment. This schedule assists the lender in determining how the debt is being paid and how much is still owed. It includes details such as the payment date, EMI, interest, principal payment, and the unpaid loan. This schedule is extremely useful in the event that the loan bearer wishes to foreclose or refinance his loan.

4.2.2 What are the factors affecting an EMI:

The EMI of a loan depends on three factors:

The cumulative amount lent by the individual is referred to as the loan amount. The rate at which interest is paid on the sum lent is referred to as the interest rate. The agreed-upon loan repayment timeframe between the borrower and the lender is referred to as the loan tenure.

4.2.3 How is EMI calculated:

The mathematical formula to calculate EMI is: EMI = P × r × (1 + r)n/((1 + r)n - 1) where P= Loan amount, r= interest rate, n=tenure in number of months.

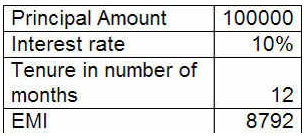

For instance, the EMI for a principal amount for Rs 1 lakh, 10% interest rate and 12 months tenure is shown in the following table:

The EMI payments are directly proportional to the loan volume and interest rates, and inversely proportional to the loan tenure, when the three governing variables are taken into account. The EMI payments increase in proportion to the loan volume or interest rate, and vice versa. While the total amount of interest to be charged increases as the loan tenure lengthens, the EMI payments decrease as the loan term lengthens.

4.2.4 Corporate bond:

A corporate bond is a financial instrument that allows a business to borrow money from an investor while paying interest and returning the principal at a later date. Corporate bond funds are debt funds that are required by regulation to invest at least 80% of their assets in companies with the highest credit rating — AAA. Companies with a high rating are usually financially sound and have a good chance of repaying their creditors on time. A corporate bond fund can invest in a variety of different instruments.

Commercial paper, shares, or debentures are examples. Each component's risk profile and maturity differs depending on the instrument.

● How are corporate bond funds taxed:

The funds are taxed in the same way as debt funds are. If an investor retains funds for less than three years, they must pay short-term capital gains tax based on their income bracket, according to the Income Tax Act. They are taxed at 20% with indexation if they carry for more than three years.

● Who should invest in a corporate bond fund:

If you have a three- to five-year time horizon and don't want to take a high risk on your debt portfolio, financial advisors recommend corporate bond funds. While such a fund carries interest rate risk, it also carries low credit risk because the portfolio contains AAA-rated paper from companies with good financials. Companies with such high ratings are more dependable.

corporates with a lower credit rating. However, a higher rating does not guarantee that the company's rating will remain stable in the future.

4.3.1What is a Principal Payment:

A principal payment is a payment made against the outstanding balance of a loan. In other words, a principal payment is a payment made on a loan that goes toward reducing the outstanding loan balance due rather than paying interest on the loan. A principal payment is any payment that reduces the amount owed on a loan in accounting and finance.

The Fixed Income Fundamentals Course at CFI delves deeper into bond principals.

4.3.2 The Basics of a Loan:

It is critical to comprehend the components of a loan. The principal and interest are two components of a loan. The interest is the fee charged to borrow the money, while the principal is the amount borrowed. Consider an individual who put aside $400,000 to buy a $1,000,000 home. To complete the transaction, they will need to borrow $600,000 from the bank. The $600,000 represents the principal – the sum lent. A bank which charge a 5% annual interest rate on the principal amount borrowed, which is the fee charged to borrow the money. The person in the scenario above would have to pay a total annual payment that included both principal and interest.

There are generally two types of loan repayment schedules:

● Even principal payments

● Even total payments

4.3.3 Even Principal Payments:

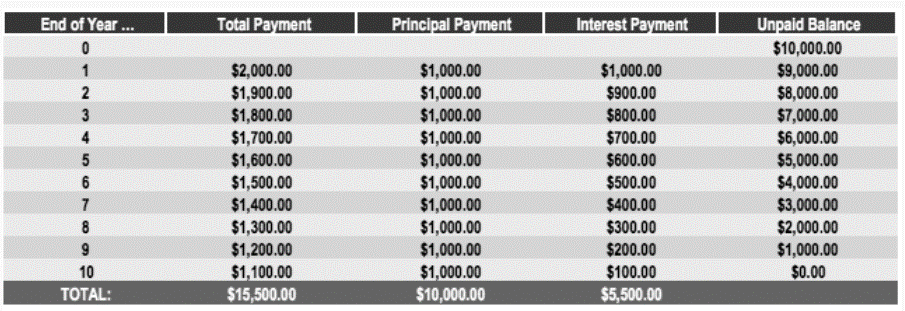

In an even principal payment loan, the principal payment amount is the same every period. Consider John, who takes a $10,000 loan with a 10% annual interest over 10 annual payments. The loan repayment schedule would look as follows:

In the loan repayment schedule above, the loan amortizes over 10 years with even principal payments of $1,000. In 10 years, the unpaid balance is $0.

The principal payment each year goes to reducing the unpaid balance. Since this amount each year is $1,000, the unpaid balance is reduced by $1,000 yearly. The interest payment is calculated on the unpaid balance. For example, the end of year one interest payment would be $10,000 x 10% = $1,000. Note that while the payment of principal remains the same, the total payment due each year, including interest, changes.

4.3.4 Even Total Payments:

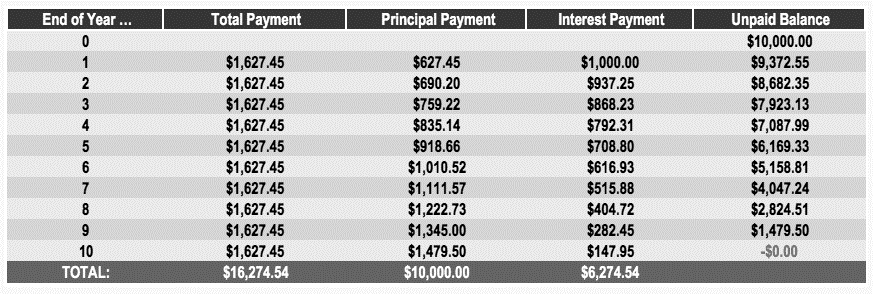

In an even total payment loan, the total payment amount is the same every period. Consider John, who takes a $10,000 loan with a 10% annual interest over 10 annual payments. The loan repayment schedule would look as follows:

In the loan repayment schedule above, the loan amortizes over 10 years with even total payments of $1,627.45. In 10 years, the unpaid balance is $0.

As opposed to an even principal payment schedule, the amount paid to principal here increases yearly. This is due to much of the initial total payment going toward paying interest rather than principal. In the first year, the amount of interest would be $10,000 x 10% = $1,000. With a total payment of $1627.45, the unpaid principal balance is only reduced by $1627.45 – $1,000 = $627.45. In such a schedule, interest payments decrease and payments on the principal increase over time.

4.3.5 Even Principal Payments vs. Even Total Payments:

The number of payments in an even principal payment plan is $15,500 over the loan's amortisation, while the total payment in an even total payment schedule is $16,274.54. This means that repaying a higher principal sum per year saves money over the course of the loan's amortisation.

A higher principal payment on a loan lowers the amount of interest due, lowering the average amount accrued over the loan's life. As a result, principal payments play a major role in the total sum owed over the course of a loan's existence.

4.3.6 Components of EMI:

The interest and principal components of an EMI can be separated. Interest payments are primarily made during the first years of a loan's tenure, with principal repayments being much fewer. The principal variable receives the majority of the repayment at the end of the repayment period.

Getting to EMI EMI is determined using a formula that takes into account the loan number, interest rate, and loan time.

4.3.7 Factors that impact EMI:

If the bank charges a high EMI, the borrower will have trouble repaying his debt. As a result, banks only lend a certain amount to ensure that home loan repayments do not exceed 40% of a borrower's monthly income. The principal sum, rate of interest, and loan tenure all affect a borrower's EMI outflow.

When the loan amount is high, the EMI repayments are also large. On the opposite, borrowing less means less EMI obligations. If interest rates do not change, EMIs will remain constant for the entire loan repayment period. EMIs on floating rate loans, on the other hand, rise as the interest rate rises and fall when the interest rate falls. Short-term home loans are normally from 5-8 years in duration. The higher the EMI due each month, the shorter the loan term. If the loan is for a limited period of time, the borrower would be debt-free earlier. Loan terms will range from 25 to 30 years. In the case of a longer term, a borrower's monthly EMI outflow decreases dramatically.

4.3.8 When EMI fluctuates:

Only in the case of 'pure' fixed rate loans does the EMI remain constant. Otherwise, it fluctuates in lockstep with market forces, inflation, and the economy. Interest rate fluctuations are a risk of floating rate loans. In the case of step-up loans, the bank lends the borrower a far larger loan today based on the borrower's expected future income levels.

In this case, the lender's EMI is lower at first and rises over time. In the case of a step-down loan, the EMI burden is high in the beginning and gradually decreases over time. Step-down loans are intended for borrowers who are nearing retirement age. Accelerated repayment is permitted by some lenders.

Borrowers can pay off their loans more quickly by rising their EMI payments. The borrower can make partial prepayments and lower his EMI contribution significantly if he receives a wage raise, a bonus, an increase in discretionary income, or lump sum funds.

There may be some unpaid expenses liabilities at the end of the year that must be accounted for in order to arrive at the correct earnings. The benefit would be overstated if all of these things are not included in the current year's Profit and Loss Account. As a result, before calculating the current year's earnings, the auditor should ensure that all such liabilities are taken into account. If he fails to do so, he will be held responsible for dividends declared out of capital as a result of those liabilities being overlooked. However, determining if all obligations have been taken into account can be difficult for an auditor.

The auditor should compare the total expenditure with the previous year and if there is an appreciable difference, he should enquire into the matter. He should also scrutinize the Purchases Book to see whether there is any suppression of purchases.

The outstanding expenses and outstanding liabilities can be brought under two heads as shown below:

Furthermore, he will gain knowledge of the nature of such unpaid liabilities through personal experience. The auditor should receive a certificate from the responsible officer stating that there are no unaccounted-for expenses for the current year. The auditor should examine nominal accounts such as wages, salaries, rent, rates, taxes, interest, discount, and so on to ensure that all expenses incurred up to the date of the Balance Sheet have been properly recorded. He could review the first few months of the next year's Cashbook payments and transactions to ensure that expenditures from the audited era were incurred in the following year.

Unearned Income

Unearned income is income that was paid during the current year but is not applicable to the current year since a portion or all of it would be earned in the following year. Rent paid in advance, interest paid in advance, and so on may all be seen as examples. As a result, unearned income that is not applicable to the audited year should not be added to the current period's Profit and Loss Account; instead, it should be recorded as a liability on the Balance Sheet.

The auditor should review the vouchers to determine the sum that should be attributed to the current year's Profit and Loss Account and the amount that should be carried forward.

Unpaid Expenses

Unpaid costs are those that were incurred in the current year but for which payment was not made in the audited year but would be made in the next year. In the event of unpaid expenses, the Profit and Loss Account should be debited with the sum and credited with the unpaid expenses, and the liability side of the Balance Sheet should reflect this.

The auditor should go at vouchers, receipts, invoices, demand notices, and other documents to see whether the costs may have been debited to the current year's Profit and Loss Account and whether no payment has been made.

4.4.1 Common items of Outstanding Liabilities and Audit Procedure:

Some of the common items of outstanding liabilities are discussed below:

Wages and Salaries: The books are usually closed on the last day of the month. Wages and bonuses for the preceding month, on the other hand, are charged within the first week of the next month. No provision will be made in the current year for the last month of the year, so wages and salaries for that month will not be debited to the current year's Profit & Loss Account. As a result, the earnings disclosed by the Profit & Loss Account will be higher than they are. As a result, such wages and salaries must be taken into account before calculating the correct profit.

In this situation, the wages and salaries account should be debited, and the remaining liabilities account should be paid for the wages and salaries that are still owed. He should also check that the Profit & Loss Account has been debited with a year's worth of wages and salaries.

Rent, Rates, Taxes, Electricity, Water, etc.: Outstanding liabilities for rent, rates, taxes, power, water, and other items must be taken into account in order to arrive at the correct benefit or loss. Otherwise, the benefit would be higher than it is. In such situations, the auditor should examine the ledger statements, demand notes, receipts, and other documents to determine the time span covered so that he can modify the accounts for sums due during the audited year.

Audit Fee: People have differing opinions about how the audit fee should be treated. Some claim that since the auditor's job begins after the books are closed, the audit fee should be considered as a cost for the following year. It should not be deducted from the profit and loss account for the audited period.

Another reason for the audit charge is that when the auditor is paying to audit the reports of the period under audit, it is reasonable to debit the Profit & Loss Account of the period under audit even though the fee has not been paid by the end of the year.

Purchase: It is not uncommon for products to be purchased from a supplier at the end of the year, but no related invoice to be received. No entry is made in the Purchases Book since the sales invoice has not been issued. The sales account should be debited and the remaining liabilities account credited for such transactions. The Purchases Book should be compared to the Goods Inward Register for the last month of the audit period.

Freight & Carriage: Freight and carriage should be determined at the end of the year and brought into accounts if clearing and forwarding agents do not make their accounts until the end of the year under audit. The auditor's job is to make sure that no part of the freight or carriage is left unaccounted for.

Commission Payable: Freight and carriage should be determined at the end of the year and brought into accounts if clearing and forwarding agents do not make their accounts until the end of the year under audit. The auditor's job is to make sure that no part of the freight or carriage is left unaccounted for.

Interest on Loans and Debts: Interest on loans and obligations that are due but not paid on the date of the Balance Sheet must be shown as an unpaid liability. In such situations, the auditor's job is to look over the previous year's account, the rate of interest, the amount of interest charged so far, and the agreement. He has to look at the ledger account to see how much interest is still owed. He should examine the books of accounts to see if correct entries have been made.

Royalty Payable: Sometimes, it so happens that the royalty may remain unpaid to a party. In such a case, the auditor should check whether proper provision is made regarding royalty due but not paid by the end of the period under audit.

Miscellaneous Expenses: A separate account is required for expenses exceeding Rs. 5000 or 1% of total revenue, whichever is higher. Other expenses do not need to be separated; they can be grouped together under the headings "miscellaneous expenses" or "general expenses."

This category includes conveyance, subscriptions, and other minor costs. Any expenses that fall under this heading but have not yet been accounted for should be reported as an unpaid liability on the balance sheet.

An outstanding debt is income earned in advance. The actual earnings can be inflated if the remaining liabilities aren't included or are understated in the financial statements. It's possible that overstating the outstanding liabilities is done to hide the true income. As a result, it is the auditor's responsibility to make certain that all outstanding liabilities are recorded.

4.5.1 What is a Sinking Fund:

A sinking fund is a collection of funds set aside or lent to repay a debt or loan. A company that issues debt will have to pay it back in the future, and a sinking fund will help with that.

A sinking fund is established such that the company can contribute to it in the years leading up to the bond's maturity date. A sinking fund enables companies that have issued debt in the form of bonds to save money over time rather than paying a large lump sum at maturity. A sinking fund function is included with some bonds.

4.5.2 Lower default risk:

A sinking fund provides investors in a corporate bond issue with some security. The risk of default on the money owed at maturity is reduced because funds are set aside to pay off the bonds at maturity. To put it another way, as a sinking fund forms, the amount owed at maturity is greatly reduced.

As a result, a sinking fund may assist creditors in obtaining protection in the event of a company's bankruptcy or default. A sinking fund also aids a corporation in reducing default risk and thereby attracting more investors to issue bonds.

4.5.3 Creditworthiness:

Interest rates on bonds are normally lower since a sinking fund adds a security aspect and reduces default risk. As a result, the business is often regarded as creditworthy, which may lead to higher debt credit ratings.

Investor demand for a company's bonds rises when it has a good credit rating, which is especially useful in the future when the company needs to issue more debt or obligations.

4.5.4 The reasoning for sinking funds:

Many people are familiar with the concept of a sinking fund and even schoolchildren recognise it as an important and reliable way to save money for something they want to purchase or own. In school, a class that wishes to end the year with a field trip to the zoo will start a sinking fund, which will have risen to the desired amount by the end of the year and will be used to cover their field trip expenses.

As a result, the students do not need to take money out of their wallets because they have been busy depositing money into their sinking fund during the year. In a nutshell, a sinking fund is proactive because it prepares an individual for the future.

4.5.5 Advantages of sinking funds:

Brings in investors

Investors are very well aware that companies or organizations with a large amount of debt are potentially risky. However, once they know that there is an established sinking fund, they will see a certain level of protection for them so that in the case of a default or bankruptcy, they will still be able to get their investment back.

● The possibility of lower interest rates

Investors would be unable to invest in a business with a low credit rating unless it offers higher interest rates. A sinking fund provides investors with an alternative form of insurance, allowing businesses to offer lower interest rates.

Stable finances

The financial position of a company is not always clear, and some financial problems may cause it to lose its footing. A sinking fund, on the other hand, ensures that a company's ability to repay loans and buy back bonds is not jeopardised. As a result, you'll have a decent credit rating and customers who are trusting in you.

Few examples

Consider a 7-Eleven franchisee who issues $50,000 in bonds with a sinking fund clause and maintains a sinking fund into which the franchisee deposits $500 on a regular basis with the intention of using it to gradually buy back bonds until they mature.

If the stock price drops, he can buy back the bonds at a reduced price, or at face value, if the market price rises. Depending on how much was bought back, the principal sum owed would eventually be lower. It's important to keep in mind, though, that the number of bonds that can be bought back before the maturity date is restricted.

Another example will be a company offering $1 million in bonds with a 10-year maturity. As a result, it establishes a sinking fund and invests $100,000 per year to ensure that all bonds are purchased by the maturity date.

4.5.6 Sinking fund vs. Savings account:

A sinking fund and a savings account are essentially the same thing in terms of putting capital aside for the future. The key distinction is that the former is set up for a specific purpose and to be used at a specific time, while the latter is set up for any purpose.

4.5.7 Sinking fund vs. Emergency fund:

The difference between a sinking fund and an emergency fund is that the former is set up for a specific reason, while the latter is set up for the unexpected.

An emergency fund, on the other hand, is set aside for an unforeseeable yet potentially catastrophic occurrence. For instance, one could set aside a certain sum as an emergency fund, which could be used in the event of a car accident, which is unforeseeable.

4.5.8 Final thoughts:

A sinking fund is very easy to start and understand. However, many people fail to create one because they lack the discipline to set aside a specific amount regularly.

Insurance companies set aside valuation reserves as required by state law to protect themselves against the possibility of their investments depreciating in value. They serve as a buffer for an investment portfolio and maintain the financial stability of an insurance company.

Since policies like life insurance, health insurance, and different annuities will last for a long time, valuation reserves shield the insurance provider from damages resulting from investments that do not perform as intended. This ensures that claimants are compensated and annuity holders are paid even though an insurance company's assets depreciate in value.

4.6.1 Understanding a Valuation Reserve:

For the services they provide, insurance companies are paid premiums. In exchange, an insurance provider must ensure that it has sufficient funds on hand to honour a client's insurance claim.

Any annuities issued by an insurance provider are subject to the same conditions. It must be certain that it will be able to fulfil the annuity's daily payments. As a result, an insurance company's reserves and investments must be closely monitored to ensure that it remains solvent. Insurance firms can do this with the aid of valuation reserves.

Insurance companies use valuation reserves to ensure that they have enough money to cover any risks associated with the contracts they have underwritten. Regulators are focusing on risk-based capital criteria to assess insurance firms' solvency, which is a perception of a company's assets and obligations separately rather than assets versus liabilities together.

4.6.2 History of valuation Reserve:

The need for valuation reserves has evolved over time. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners required a mandatory securities valuation reserve for insurance companies prior to 1992 to protect against a loss in the value of the securities they held.

The required securities valuation reserve provisions were modified after 1992 to include an asset valuation reserve as well as an interest maintenance reserve. This mirrored the essence of the insurance industry, with firms keeping various types of assets and consumers buying annuity-related products in greater numbers.

4.6.3 Changing Valuation Reserve Requirements:

Companies that sell life insurance and annuities have a legal duty to compensate beneficiaries. These businesses must keep a sufficient amount of assets in place to ensure that they can fulfil their commitments for the duration of the policies.

This degree must be measured on an actuarial basis under various state laws and requirements. This method takes into account projected claims from policyholders, as well as projections for potential premiums and the amount of interest a business would expect to gain.

In the 1980s, however, the demand for insurance and annuity products was changing. According to the American Council of Life Insurers, life insurance accounted for 51 percent of company reserves in 1980, while individual annuity reserves accounted for just 8%. Then, by 1990, life insurance reserves had fallen to 29 percent of total reserves, while individual annuity reserves had risen to 23 percent. This represented the rise in popularity of insurance-sponsored retirement plans.

A shifting interest rate environment poses a greater risk to reserves required for continuing annuity payments than for life insurance premiums paid in a lump sum. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners acknowledged the need to guard against changes in the value of equity and credit-related capital gains and losses differently than interest-related gains and losses by proposing that laws be changed to distinguish asset valuation reserves from interest maintenance reserves.

4.6.4 Risk-Based Capital Requirements

Rather than rules that regulate insurance companies' contracts and investments, regulators are gradually implementing risk-based capital provisions to ensure their protection and soundness.

The regulations describe a company's risk based on the characteristics of its assets and responsibilities, rather than the combination of assets and liabilities. As a result, risk-based capital regulations deny businesses that diversify their investments or balance the terms of their assets and liabilities to reduce risks a lot of credit.

Market and book prices are used to value insurers' assets in the current steps. In the end, this strategy misrepresents a company's ability to overcook.

It means that a robust measure of a company’s ability to mitigate risk rests on a judgment about the odds of the anticipated and unexpected economic conditions, not to mention the implied relationship between return and investments.

The ever-changing premiums and interest rate portfolios will draw risks that wreak havoc on the reserves required to pay annuities on a regular basis. Despite the fact that policyholders do not view all insurance policies as investments, the premium for all contracts is determined by the returns that insurers expect to receive on their reserves.

In light of this, the NAIC called for market-strengthening initiatives.

Surrendering an insurance policy means cashing it out before the payments are due. The Surrender Value of an Insurance Policy is the amount paid to the insured if he is unable to pay the insurance policy's premium. When the insured is unable to pay any more premiums and has already paid premiums on a surrendered insurance policy. It refers to the cash value of an insurance policy at a certain point in time. It's the sum of premiums charged or any amount recoverable on an insurance policy if it's cancelled soon after it's been released.

The cash surrender value is the amount of money paid by an insurance agent to a policyholder or annuity contract owner if the policy is voluntarily terminated before its expiration date or if an insured occurrence occurs.

This cash value is the savings component of most permanent life insurance policies, especially whole life insurance policies, and it is available to the policyholder over his lifetime, depending on the type of policy.

4.7.1 CASH VALUE:

The amount of money that accumulates within a cash value-generating annuity or permanent life insurance policy is referred to as cash value, or account value. It's the money in your bank account. Your insurance or annuity company invests some of the money you pay in premiums—for example, in a bond portfolio—and then rewards the policy depending on how well those investments do.

4.7.2 SURRENDER VALUE:

If a policyholder tries to access the cash value of the policy, the surrender value is the amount of money they will get. The surrender cash value or, in the case of annuities, the annuity surrender value are two other terms for the surrender cash value. When cash is withdrawn early from a policy, there is frequently a penalty assessed.

4.7.3 Calculation of surrender value:

The Formula generally used for Calculation of Special Surrender Value is;

SSV= {BSAx (NP/TNP+BR} Xsvf

Or

Special Surrender Value= {Basic Sum Assured (Number of premium paid/Total Number of premiums payable) + Bonus received} Surrender Value Factor

The Surrender Value depends the number of years you have paid the premium and bonus received during tenure of policy.

There are two types of Surrender Value;

GUARANTEED SURRENDER VALUE:

is often stated in policy papers, and the Special/Cash Surrender Value will be determined when the insured submits a surrender request.

NOTE: If an insured has paid premiums for the previous three years, he is liable for Guaranteed Surrender Value. It is 30% of the premium earned that is less than the first year premium charged.

Example: Let’s us consider Mr. A has taken an insurance SA Rs. 5,00,000/- for a period of 20 years and premium payment Rs. 25,000/- for annually. He has paid three premiums at the time of requesting surrender of policy. In this case total premium paid by him is Rs. 75,000/-. Now in this case he will received (75000-25000) *30/100= Rs. 15000 only.

SPECIAL OR CASH SURRENDER VALUE:

Before we can grasp unique surrender value, we must first comprehend paid-up value. If you don't pay your premiums after a certain period of time, your policy will continue, but at a lower amount guaranteed. The term "paid-up value" or "paid-up sum guaranteed" refers to the reduced sum assured.

The original amount guaranteed is multiplied by the ratio of the number of premiums paid to the number of premiums payable to arrive at the paid-up value.

Example:

Mr. A paid the Rs 25,000 annual premium on a quarterly basis, and the sum assured is Rs 5 lakh for a policy term of 20 years. If Mr. A stop paying after three years, that is, have paid 12 premiums, the paid-up value will be Rs 5,00,000X (12/80).

In this case, 80 (20X4) is the number of premiums you were supposed to pay and 12 (3X4) is the number of premiums you have actually paid.

The paid-up value is Rs 75,000. This is the sum you will get at maturity or your nominee will get after you die. Paid-up value plus bonus is the total paid-up value. Mr. A has accumulated bonus of Rs. 60,000 as bonus.

Total Premium payment terms= 20*4=80

Total Premium paid=3*4= 12

Total Paid Up Value= Total Premium Paid + Bonus Accumulated=Rs. 75000+ Rs. 60000=Rs. 135000

Surrender Value factor= 27.76%

Special Cash/Surrender Value= {500000*12/80+60000)} Surrender Value Factor=135000*27.76%= Rs. 37,260/-

4.8.1 Meaning of Security Valuation:

When deciding on an investor's portfolio, security valuation is critical. All investment decisions must be based on a scientific examination of the correct share price. As a result, knowledge of securities valuation is needed. Investing in underpriced stocks and selling overpriced stocks is a good strategy. As a result, share pricing is a crucial part of the trading process. In terms of concept, there are four different types of valuation models.

They are:

(i) Book value,

(ii) Liquidating value,

(iii) Intrinsic value,

(iv) Replacement value as compared to market price.

● Book Value:

A security's book value is an accounting term. The book value of an equity share is calculated by dividing the firm's net worth by the number of equity shares, where net worth is defined as equity capital plus free reserves. The stock value of a company may fluctuate around the book value, but it may be higher if the potential prospects are promising.

● Liquidating Value (Breakdown Value):

If the assets are valued at their market breakdown value, then the liquidating value per share is calculated by dividing net fixed assets plus current assets minus current liabilities as if the company is liquidated by the number of shares. This is an accounting term as well.

● Intrinsic Value:

A security's market value is the price at which it is sold in the market, and it is usually close to its intrinsic value. When it comes to the relationship between intrinsic value and market price, there are many schools of thought. Market prices are those that govern the market as a result of supply and demand powers. The intrinsic price of a stock is its true value, which is determined by its earning ability and true worth. The value of a security must be equal to the discounted value of the potential income stream, according to the fundamentalist approach to security valuation. If the stock price is below this value, the investor purchases the securities.

Thus, for fundamentalists, earnings and dividends are the essential ingredients in determining the market value of a security. The discount rate used in such present value calculations is known as the required rate or return. Using this discount rate all future earnings are discounted back to the present to determine the intrinsic value.

The price of a security, according to the technical school, is determined by market demand and supply and has very little to do with intrinsic values. For different periods of time, market fluctuations follow those patterns. The predictable shifts in demand and supply are represented by changes in trend. According to this school, current trends are a byproduct of the past, and history repeats itself.

Market prices are good substitutes for intrinsic values in a reasonably broad defence market where competitive conditions prevail, according to the efficient market hypothesis. After taking into account all of the information available to market participants, security prices are calculated.A share is thus generally worth whatever it is selling for in the market.

Generally, fundamental school is the basis for security valuation and many models are in use, based on these tenets.

● Replacement Value:

The replacement value of a share would vary from the Breakdown value when the company is liquidated and its assets are to be replaced with new ones at higher rates. This replacement value is used by some analysts to equate to the market price.

4.8.2 Factors Influencing Security Valuation:

The value of a security is determined by a variety of variables, including earnings per share, expansion opportunities, future earnings potential, the possibility of issuing bonus or rights shares, and so on. Some demand for a specific stock can provide a sense of power as a shareholder, as well as prestige and management control. In a realistic and quantifiable sense, satisfaction and enjoyment in the non-monetary sense cannot be considered. The demand for a share is influenced by a variety of psychological and emotional factors.

In money terms, the return to a security on which its value depends consists of two components:

(i) Regular dividends or interest, and

(ii) Capital gains or losses in the form of changes in the capital value of the asset.

When the risk is high, the reward should be high as well. The uncertainty of receiving principal and interest, or a dividend, as well as the variability of this return, is referred to as risk.

The above returns are expressed in terms of the amount of money received over time. However, Re's money Today's 1 isn't the same as Re's money. 1 year from now, two years from now, and so on. Money has a time value, so earlier receipts are more valuable and desirable. One explanation for this is that older receipts can be reinvested, and more receipts can be obtained than previously. Compound interest is the key principle at work here.

Thus, if Vn is the terminal value at the period n, P is the initial value, g is rate of compounding or return, n is the number of compounding periods, then Vn = P (1 + g)n.

If we reverse the process, the present value (P) can be thought of as reversing the compounding of values. This is discounting of the future values to the present day, represented by the formula-

P = Vn /(1+ g)n

where the meaning of the terms used is the same as indicated above.

The return on equity capital to the investor is the most important factor that affects security prices. This return may be in the form of dividends or the company's net earnings. As a result, the value of a share is determined by the company's ability to pay dividends or raise money. Dividends may vary from earnings depending on the amount of profit retained by the company for liquidity, growth, modernization, and other purposes.

If the shares are not traded on the market, the value of a share is usually its book value. The market price of shares quoted, on the other hand, would vary from the book value based on investors' perceptions of the company's future profit potential, growth prospects and business prospects, management efficiency, and the company's goodwill or intangibles.

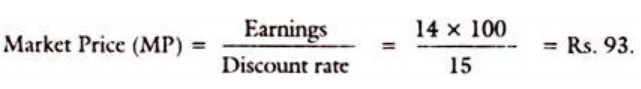

If the security is a bond or debenture with a fixed return, such as 14% per year, the market price is determined by the investor's understanding of the capitalization rate, which is commonly believed to be 15%.

In this case-

If the security is an equity share, its return is Dividend + Capital appreciation. Then the future dividends may not be constant or fixed as also the degree, of capital appreciation.

4.8.3 Graham’s Approach to Valuation of Equity

Benjamin Graham and David Dodd argued in their book Security Analysis (1934) that potential earnings power was the most significant determinant of stock value. The original method for determining an undervalued stock was to calculate the present value of expected dividends and compare it to the current market price. If the current market price is lower, the stock is undervalued. Alternatively, the analyst could calculate a discount rate that equals the current market price of the stock when the forecasted dividends are discounted. The stock is underpriced if the rate (I.R.R. or discount rate) is higher than the appropriate rate for stocks with equivalent risks.

The CCI used to value securities in India for the purpose of determining the premium on new issues of existing companies. These CCI guidelines remained in effect until May 1992, when the CCI was decommissioned. Although the current market price will be considered, the CCI will calculate a more realistic price based on certain parameters.

As a result, the CCI based the premium on shares on the concepts of Net Asset Value (NAV) and Profit-Earning Capacity Value (PECV). The net asset value (NAV) is determined by dividing the net worth by the number of equity shares outstanding. The net worth of a company is made up of its equity capital, free assets, and surplus, minus any contingent liabilities.

The PECV is calculated by multiplying earnings per share by a capitalisation rate of 15% for manufacturing firms, 20% for trading firms, and 17.5% for intermediate firms. The three-year average post-tax income are divided by the total number of equity shares to measure Earnings Per Share (EPS).

Thus, if EPS is Rs. 5 and if the price earnings multiplier is 15, the price of share, which is reflected by the PECV, should be Rs. 5 x 15 = 75 (if it is a manufacturing company).

To be more specific, Total assets minus liabilities, borrowings, debts, option stock, and contingent liabilities separated by the number of shares equals Net Asset Value (NAV).

The (PECV) is calculated by capitalising the average after-tax income (over the previous three years) at a rate ranging from 15% to 20%, depending on the nature of the company's operation.

The average of the NAV and PECV is the share's fair value. This Fair Value (FV) is used to compare to the average market price over the previous three years, and the average market price should be at least 20% less than the fair value. The capitalisation rate to be used is 12 percent if the average selling price is 20 percent to 50 percent of the FV. The capitalisation rate is 10% if it is between 50% and 75% of the FV, and it is 8% if it is greater than 75% of the FV.

Example:

This example will make the above exercise clear (year 1990).

Take a manufacturing company (TISCO)

Average Market Price over the last three years = Rs. 123

Net Asset Value (NAV) computed as shown above = Rs. 68

Profit-Earning Capacity Value (PECV) = Earnings per share Rs. 5.4

capitalised by 15% for manufacturing company = 5.4×100/15 = Rs. 36.

Average of NAV and PECV is (68 + 36)/2 = Rs. 52 which is the fair value.

The market price is more than 75% of the Fair Value (Rs. 52). Hence, the capitalisation rate of 8% is to be applied as referred to above to the earnings per share.

Earnings per share is Rs. 5.4.

At the capitalisation rate of 8%, the PECV = Rs. 67.50.

Book value per share or NAV is Rs. 68.

The average of the two above is Rs. 67.75.

For a share of Rs. 10 of face value, the premium is thus Rs. 57.75.

With the repeal of the C.I.C. Act in May 1992, free market pricing of shares became possible. The business and its merchant banker will decide on the price of a new issue. According to SEBI's current guidelines, the merchant banker is not required to send proposals for new issues' share price, premium, if any, or other terms to the SEBI for vetting, but the reason for the same must be included in the prospectus. To adjust the actual premium from the premium submitted to SEBI for record or vetting, a margin of 20% on either side is allowed.

References