The origin of the financial crisis can be traced from the inefficient management of the Indian economy in the 1980s. We know that for implementing various policies and its general administration, the government generates funds from various sources such as taxation, running of public sector enterprises etc. When expenditure is more than income, the government borrows to finance the deficit from banks and also from people within the country and from international financial institutions. When we import goods like petroleum, we pay in dollars which we earn from our exports.

Development policies required that even though the revenues were very low, the government had to overshoot its revenue to meet problems like unemployment, poverty and population explosion. The continued spending on development programmes of the government did not generate additional revenue. Moreover, the government was not able to generate sufficiently from internal sources such as taxation. When the government was spending a large share of its income on areas which do not provide immediate returns such as the social sector and defence, there was a need to utilise the rest of its revenue in a highly efficient manner. The income from public sector undertakings was also not very high to meet the growing expenditure. At times, our foreign exchange, borrowed from other countries and international financial institutions, was spent on meeting consumption needs. Neither was an attempt made to reduce such profligate spending nor sufficient attention was given to boost exports to pay for the growing imports.

In the late 1980s, government expenditure began to exceed its revenue by such large margins that meeting the expenditure through borrowings became unsustainable. Prices of many essential goods rose sharply. Imports grew at a very high rate without matching growth of exports. As pointed out earlier, foreign exchange reserves declined to a level that was not adequate to finance imports for more than two weeks. There was also not sufficient foreign exchange to pay the interest that needs to be paid to international lenders. Also no country or international funder was willing to lend to India.

India approached the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), popularly known as World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and received $7 billion as loan to manage the crisis. For availing the loan, these international agencies expected India to liberalise and open up the economy by removing restrictions on the private sector, reduce the role of the government in many areas and remove trade restrictions between India and other countries.

India agreed to the conditionalities of World Bank and IMF and announced the New Economic Policy (NEP). The NEP consisted of wide-ranging economic reforms. The thrust of the policies was towards creating a more competitive environment in the economy and removing the barriers to entry and growth of firms. This set of policies can broadly be classified into two groups: the stabilisation measures and the structural reform measures. Stabilisation measures are short term measures, intended to correct some of the weaknesses that have developed in the balance of payments and to bring inflation under control. In simple words, this means that there was a need to maintain sufficient foreign exchange reserves and keep the rising prices under control. On the other hand, structural reform policies are long-term measures, aimed at improving the efficiency of the economy and increasing its international competitiveness by removing the rigidities in various segments of the Indian economy. The government initiated a variety of policies which fall under three heads liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation.

As pointed out in the beginning, rules and laws which were aimed at regulating the economic activities became major hindrances in growth and development. Liberalisation was introduced to put an end to these restrictions and open up various sectors of the economy. Though a few liberalisation measures were introduced in 1980s in areas of industrial licensing, export-import policy, technology upgradation, fiscal policy and foreign investment, reform policies initiated in 1991 were more comprehensive. Let us study some important areas such as the industrial sector, financial sector, tax reforms, foreign exchange markets and trade and investment sectors which received greater attention in and after 1991.

Deregulation of Industrial Sector: In India, regulatory mechanisms were enforced in various ways (i) industrial licensing under which every entrepreneur had to get permission from government officials to start a firm, close a firm or to decide the amount of goods that could be produced (ii) private sector was not allowed in many industries (iii) some goods could be produced only in small scale industries and (iv) controls on price fixation and distribution of selected industrial products.

The reform policies introduced in and after 1991 removed many of these restrictions. Industrial licensing was abolished for almost all but product categories — alcohol, cigarettes, hazardous chemicals, industrial explosives, electronics, aerospace and drugs and pharmaceuticals. The only industries which are now reserved for the public sector are defence equipments, atomic energy generation and railway transport. Many goods produced by small scale industries have now been dereserved. In many industries, the market has been allowed to determine the prices.

Financial Sector Reforms: Financial sector includes financial institutions such as commercial banks, investment banks, stock exchange operations and foreign exchange market. The financial sector in India is regulated by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). You may be aware that all the banks and other financial institutions in India are regulated through various norms and regulations of the RBI. The RBI decides the amount of money that the banks can keep with themselves, fixes interest rates, nature of lending to various sectors etc. One of the major aims of financial sector reforms is to reduce the role of RBI from regulator to facilitator of financial sector. This means that the financial sector may be allowed to take decisions on many matters without consulting the RBI.

The reform policies led to the establishment of private sector banks, Indian as well as foreign. Foreign investment limit in banks was raised to around 50 per cent. Those banks which fulfil certain conditions have been given freedom to set up new branches without the approval of the RBI and rationalise their existing branch networks. Though banks have been given permission to generate resources from India and abroad, certain managerial aspects have been retained with the RBI to safeguard the interests of the accountholders and the nation. Foreign Institutional Investors (FII) such as merchant bankers, mutual funds and pension funds are now allowed to invest in Indian financial markets.

Tax Reforms: Tax reforms are concerned with the reforms in government’s taxation and public expenditure policies which are collectively known as its fiscal policy. There are two types of taxes: direct and indirect. Direct taxes consist of taxes on incomes of individuals as well as profits of business enterprises. Since 1991, there has been a continuous reduction in the taxes on individual incomes as it was felt that high rates of income tax were an important reason for tax evasion. It is now widely accepted that moderate rates of income tax encourage savings and voluntary disclosure of income. The rate of corporation tax, which was very high earlier, has been gradually reduced. Efforts have also been made to reform the indirect taxes, taxes levied on commodities, in order to facilitate the establishment of a common national market for goods and commodities. Another component of reforms in this area is simplification. In order to encourage better compliance on the part of taxpayers many procedures have been simplified and the rates also substantially lowered.

Foreign Exchange Reforms: The first important reform in the external sector was made in the foreign exchange market. In 1991, as an immediate measure to resolve the balance of payments crisis, the rupee was devalued against foreign currencies. This led to an increase in the inflow of foreign exchange. It also set the tone to free the determination of rupee value in the foreign exchange market from government control. Now, more often than not, markets determine exchange rates based on the demand and supply of foreign exchange.

Trade and Investment Policy Reforms: Liberalisation of trade and investment regime was initiated to increase international competitiveness of industrial production and also foreign investments and technology into the economy. The aim was also to promote the efficiency of the local industries and the adoption of modern technologies

In order to protect domestic industries, India was following a regime of quantitative restrictions on imports. This was encouraged through tight control over imports and by keeping the tariffs very high. These policies reduced efficiency and competitiveness which led to slow growth of the manufacturing sector. The trade policy reforms aimed at (i) dismantling of quantitative restrictions on imports and exports (ii) reduction of tariff rates and (iii) removal of licensing procedures for imports. Import licensing was abolished except in case of hazardous and environmentally sensitive industries. Quantitative restrictions on imports of manufactured consumer goods and agricultural products were also fully removed from April 2001. Export duties have been removed to increase the competitive position of Indian goods in the international markets.

Privatization:

It implies shedding of the ownership or management of a government owned enterprise. Government companies are converted into private companies in two ways (i) by withdrawal of the government from ownership and management of public sector companies and or (ii) by outright sale of public sector companies. Privatisation of the public sector enterprises by selling off part of the equity of PSEs to the public is known as disinvestment. The purpose of the sale, according to the government, was mainly to improve financial discipline and facilitate modernisation. It was also envisaged that private capital and managerial capabilities could be effectively utilised to improve the performance of the PSUs.

The government envisaged that privatisation could provide strong impetus to the inflow of FDI. The government has also made attempts to improve the efficiency of PSUs by giving them autonomy in taking managerial decisions. For instance, some PSUs have been granted special status as maharatnas, navratnas and miniratnas (see Box 3.1). 3.5 GLOBALISATION Although globalisation is generally understood to mean integration of the economy of the country with the world economy, it is a complex phenomenon. It is an outcome of the set of various policies that are aimed at transforming the world towards greater interdependence and integration. It involves creation of networks and activities transcending economic, social and geographical boundaries. Globalisation attempts to establish links in such a way that the happenings in India can be influenced by events happening miles away. It is turning the world into one whole or creating a borderless world.

Outsourcing:

This is one of the important outcomes of the globalisation process. In outsourcing, a company hires regular service from external sources, mostly from other countries, which was previously provided internally or from within the country (like legal advice, computer service, advertisement, security — each provided by respective departments of the company). As a form of economic activity, outsourcing has intensified, in recent times, because of the growth of fast modes of communication, particularly the growth of Information Technology (IT). Many of the services such as voice-based business processes (popularly known as BPO or call centres), record keeping, accountancy, banking services, music recording, film editing, book transcription, clinical advice or even teaching are being outsourced by companies in developed countries to India. With the help of modern telecommunication links including the Internet, the text, voice and visual data in respect of these services is digitised and transmitted in real time over continents and national boundaries. Most multinational corporations, and even small companies, are outsourcing their services to India where they can be availed at a cheaper cost with reasonable degree of skill and accuracy. The low wage rates and availability of skilled manpower in India have made it a destination for global outsourcing in the post-reform period.

Global Footprint:

Owing to globalisation, you might find many Indian companies have expanded their wings to many other countries. For example, ONGC Videsh, a subsidiary of the Indian public sector enterprise, Oil and Natural Gas Corporation engaged in oil and gas exploration and production has projects in 16 countries. Tata Steel, a private company established in 1907, is one of the top ten global steel companies in the world which have operations in 26 countries and sell its products in 50 countries. It employs nearly 50,000 persons in other countries. HCL Technologies, one of the top five IT companies in India has offices in 31 countries and employs about 15,000 persons abroad. Dr Reddy's Laboratories, initially was a small company supplying pharmaceutical goods to big Indian companies, today has manufacturing plants and research centres across the world.

World Trade Organisation (WTO):

The WTO was founded in 1995 as the successor organisation to the General Agreement on Trade and Tariff (GATT). GATT was established in 1948 with 23 countries as the global trade organisation to administer all multilateral trade agreements by providing equal opportunities to all countries in the international market for trading purposes. WTO is expected to establish a rule-based trading regime in which nations cannot place arbitrary restrictions on trade. In addition, its purpose is also to enlarge production and trade of services, to ensure optimum utilisation of world resources and to protect the environment. The WTO agreements cover trade in goods as well as services to facilitate international trade (bilateral and multilateral) through removal of tariff as well as non-tariff barriers and providing greater market access to all member countries. As an important member of WTO, India has been in the forefront of framing fair global rules, regulations and safeguards and advocating the interests of the developing world. India has kept its commitments towards liberalisation of trade, made in the WTO, by removing quantitative restrictions on imports and reducing tariff rates.

Some scholars question the usefulness of India being a member of the WTO as a major volume of international trade occurs among the developed nations. They also say that while developed countries file complaints over agricultural subsidies given in their countries, developing countries feel cheated as they are forced to open up their markets for developed countries but are not allowed access to the markets of developed countries.

Key takeaways:

1) Development policies required that even though the revenues were very low, the government had to overshoot its revenue to meet problems like unemployment, poverty and population explosion. The continued spending on development programmes of the government did not generate additional revenue.

2) Liberalisation was introduced to put an end to these restrictions and open up various sectors of the economy. Though a few liberalisation measures were introduced in 1980s in areas of industrial licensing, export-import policy, technology upgradation, fiscal policy and foreign investment, reform policies initiated in 1991 were more comprehensive.

3) In India, regulatory mechanisms were enforced in various ways (i) industrial licensing under which every entrepreneur had to get permission from government officials to start a firm, close a firm or to decide the amount of goods that could be produced (ii) private sector was not allowed in many industries (iii) some goods could be produced only in small scale industries and (iv) controls on price fixation and distribution of selected industrial products.

4) The reform policies led to the establishment of private sector banks, Indian as well as foreign.

5) Privatization implies shedding of the ownership or management of a government owned enterprise. Government companies are converted into private companies in two ways (i) by withdrawal of the government from ownership and management of public sector companies and or (ii) by outright sale of public sector companies.

6) Outsourcing is one of the important outcomes of the globalisation process. In outsourcing, a company hires regular service from external sources, mostly from other countries, which was previously provided internally or from within the country (like legal advice, computer service, advertisement, security — each provided by respective departments of the company).

Reforms in Agriculture: Reforms have not been able to benefit agriculture, where the growth rate has been decelerating. Public investment in the agriculture sector especially in infrastructure, which includes irrigation, power, roads, market linkages and research and extension (which played a crucial role in the Green Revolution), has fallen in the reform period. Further, the removal of fertiliser subsidy has led to increase in the cost of production, which has severely affected the small and marginal farmers. This sector has been experiencing a number of policy changes such as reduction in import duties on agricultural products, removal of minimum support price and lifting of quantitative restrictions on agricultural products; these have adversely affected Indian farmers as they now have to face increased international competition. Moreover, because of export oriented policy strategies in agriculture, there has been a shift from production for the domestic market towards production for the export market focusing on cash crops in lieu of production of food grains. This puts pressure on prices of food grains.

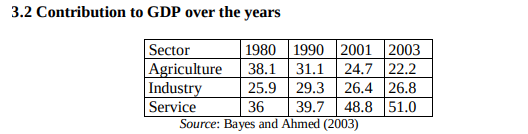

Agriculture is an important part of India's economy and at present it is among the top two farm producers in the world. This sector provides approximately 52 percent of the total number of jobs available in India and contributes around 18.1 percent to the GDP. Agriculture is the only means of living for almost two-thirds of the employed class in India. As stated by the economic data of financial year 2006-07, agriculture has acquired 18 percent of India's GDP. The agriculture sector of India has occupied almost 43percent of India's geographical area.

Agriculture plays a vital role in the Indian economy. Over 70 per cent of the rural households depend on agriculture. Agriculture is an important sector of Indian economy as it contributes about 17% to the total GDP and provides employment to over 60% of the population. Indian agriculture has registered impressive growth over the last few decades. The food grain production has increased from 51 million tonnes (MT) in 1950-51 to 250MT during 2011-12 highest ever since independence.

Current Status :

1. The Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Ministry of Agriculture (DESMOA) is responsible for the collection,.(a) weekly and daily wholesales prices, (b) retail prices of essential commodities, (c) farm harvest prices.

2. Weekly wholesale prices cover 140 agricultural commodities from 620 markets.

3. Retail prices of essential commodities are collected on a weekly basis from 83 market centres in respect of 88 commodities (49 food and 39 non-food) by the staff of the State Market Intelligence Units, State Directorates of Economics and Statistics (DESs) and State Department of Food and Civil Supplies.

4. Farm Harvest Prices are collected by the field staff of the State revenue departments for 31 commodities at the end of each crop season and published by the DESMOA.

Some salient facts about Agricultural scenario

Trends in agricultural production and productivity, Factors determining productivity; Land Reforms; New agricultural strategy and Green Revolution

Since the introduction of economic planning in India, agricultural development has been receiving a special emphasis. It was only after 1965, i.e., from the mid-period of the Third Plan, special emphasis was laid on the development of the agricultural sector. Since then, a huge amount of fund was allocated for the development and modernization of this agricultural sector every year.

All these initiatives have led to:

a) A steady increase in areas under cultivation;

b) A steady rise in agricultural productivity; and

c) A rising trend in agricultural production.

Growth in Area:

In India the growth in gross area under all crops has increased from 122 million hectares in 1949-50 to 151 million hectares in 1964-65 and then it increased to 168.4 million hectares in 2008- 09. Further, gross area under all food grains has increased from 99 million hectares in 1949-50 to 118 million hectares in 1964-65 and then to 123.2 million hectares in 2008-09. Similarly, the gross area under all non-food-grains has also increased from 23 million hectares in 1949-50 to 33 million hectares in 1964-65 and then to 45.2 million hectares in 2008-09.

In India, out of the total cultivable area of 186 million hectares, the net sown area is estimated at 143 million hectares. Moreover, the areas under cultivation of all crops have increased by 0.25 per cent during the period 1980-81 to 1995-96 as compared to 0.51 per cent during 1967-68 to 1980-81. Again, the area under food-grain cultivation has decline by 0.32 per cent per annum between 1980-81 to 1995-96 as compared to an increase in the area of the tune of 0.38 per cent between 1967-68 and 1980-81.

During the pre-green revolution period, i.e., during 1951-65 additional area including marginal lands, fallow lands, waste lands and forest lands were brought under cultivation. The annual rate of growth in area under crops during the period 1950-65 was quite substantial.

All crops: 1.6 per cent, Food grains: 1.4 percent and Non-food grains: 2.5 per cent. But in the post-green revolution period, i.e., during 1965-95, the area under all crops could not increase significantly and the annual growth rate in the area was also quite minimum—All crops: 0.3 per cent, Food-grains: 1.2 percent and Non- food-grains: 0.7 per cent.

Agricultural Productivity:

By the term agricultural productivity, we mean the varying relationship between the agricultural output and one of the major inputs such as land. The most commonly used term for representing agricultural productivity is the average yield per hectare of land.

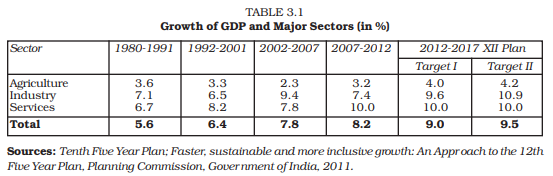

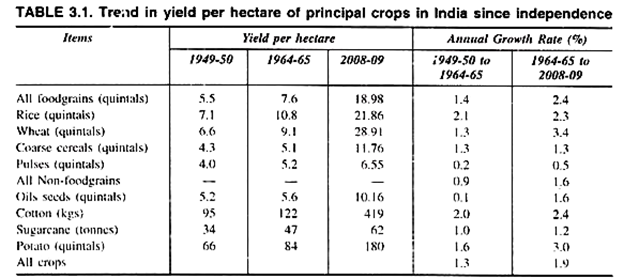

The Table 3.1 reveals that in India the average yield per hectare for all food-grains has recorded an increase from 5.5 quintals in 1949-50 to 7.6 quintals in 1964-65 and then to 18.98 quintals in 2008- 09 showing an annual growth rate of 1.4 per cent during 1950-65 and 2.4 per cent during 1965-2007.

Moreover, the average yield per hectare in respect of rice and wheat which were 7.1 quintals and 6.6 quintals respectively in 1949-50 gradually increased to 10.8 quintals and 9.1 quintals in 1964-65 showing an annual growth rate of 2.1 per cent and 1.3 per cent in respect of rice and wheat respectively.

Again during the post-green revolution period (1965-2009), the average yield per hectare in respect of rice and wheat has again increased to 21.86 quintals and 28.91 quintals respectively showing a considerable annual growth rate of 3.4 per cent in respect of wheat and 2.3 per cent in respect of rice. But the annual growth rate of coarse cereals increased by only 1.3 per cent and that of pulses of only 0.5 per cent during the period 1967-2009. Moreover, the annual growth rate of yield per hectare of all crops went up to 2.49 per cent during the period 1980-81 to 1993-94 as compared to that of 1.28 per cent during 1967-68 to 1980-81.

Among the non-food-grains, cotton and sugarcane achieved a modest growth rate of 2.0 per cent and 1.0 per cent respectively during 1950-65 and again to the extent of 2.4 per cent and 1.2 per cent respectively during 1967-2009.

Moreover, potato has recorded a considerable increase in annual growth rate from 1.6 per cent during 1950-65 to 3.0 per cent during 1967-2009. Again, taking all crops together, the annual average growth rate of all crops rose from 1.3 per cent during 1950-1965 to 1.9 per cent during 1967-2009. Thus, the above data reveal that the green revolution and the application of new bio-chemical technology have become very much effective only in case of wheat and potato but proved ineffective in case of other crops.

Moreover, if we compare the average yield per hectare of various crops in India with foreign countries then we find that India lags far behind the other developed countries of the world. In 1990- 91, the annual average yield of rice per hectare was only 17.5 quintals in India as against 41 quintals in U.S.A., 61.9 quintals in Japan and 54 quintals in China. Again, the annual average yield of wheat per hectare was only 22.7 quintals in India as against 68 quintals in Germany, 61 quintals in France and 30 quintals in China.

Trends in Agricultural Production:

Agricultural production in India can be broadly classified into food crops and commercial crops. In India the major food crops include rice, wheat, pulses, coarse cereals etc. Similarly, the commercial crops or non-food crops include raw cotton, tea, coffee, raw jute, sugarcane, oil seeds etc.

In India, total agricultural production has been increasing with the combined effect of growth in total cultivated areas and increases in the average yield per hectare of the various crops. Table 3.2 reveals the trend in total agricultural production in India since independence.

Trends and Growth Rate of Production of Agricultural Crops Since 1949-50:

The Table 3.2 reveals that total production of food grains had increased from 55 million tonnes in 1949-50 to 89 million tonnes in 1964-65 and then increased to 176 million tonnes in 1990-91. But in 1991-92, total production of food grains came down to 167 million tonnes mainly due to fall in the production of coarse cereals and in 1993-94, the production was around 184 million tonnes.

In 2002- 03, total production of food grains has further decreased to 174.8 million tonnes. As per advance estimates, total production of food grains has again increased to 233.9 million tonnes in 2008-09. Thus in the pre-green revolution period (1950-65) the food grains production had experienced an impressive annual growth rate of 3.2 per cent and in the post-green revolution period (1967-2007), the same annual growth rate was to the extent of 2.7 per cent.

The major cereals like rice and wheat recorded a high growth rate, i.e., 3.5 and 4.0 per cent respectively during the first period (1950-65) and again to the extent of 2.2 and 5.0 per cent respectively during the second period (1967-2007). But the growth rate in coarse cereals and pulses remained quite marginal.

Total production of rice and wheat have increased from 24 million tonnes and 6 million tonnes in 1949-50 to 39 million tonnes and 12 million tonnes in 1964-65 and then to 99.2 million tonnes and 80.6 million tonnes respectively in 2008-09. In respect of non-food grains the trends in production in respect of potato and sugarcane were quite impressive and that of cotton and oilseeds were not up to the mark.

The table further shows that the new agricultural strategy could not bring a break-through in agricultural output of the country excepting wheat and potato which recorded about 4.8 per cent and 6.7 per cent annual growth rate respectively during the post-green revolution period. The growth in output in respect of all other crops remained low and that of coarse cereals and pulses were only marginal where the annual growth rates were only 0.4 and 1.04 per cent respectively.

From the above analysis we can draw the following important observations:

(i) In the pre-green revolution period, the growth of output has mainly contributed by the growth or expansion in area but in the post-green revolution period, improvement in agricultural productivity arising from the adoption of modern technique has contributed to growth in output.

(ii) In-spite of adopting modern technology, the growth rate in output, excepting wheat could not maintain a steady level.

(iii) During the post-green revolution period the growth rate in output was comparatively lower than the first annual growth rate in food grains was maintained at the level of 2.7 per cent in the second period.

(iv) The growth rate in output of oil seeds, pulses and coarse food grains declined substantially in the second period as the cultivation of these crops have been shifted to inferior lands.

(v) Although agricultural production attained a substantial increase since independence, these production trends have been subjected to continuous fluctuations mainly due to variation of monsoons and other natural factors.

Land Reforms; New agricultural strategy and Green Revolution:

Introduction of New Agricultural Strategy:

The new agricultural strategy was adopted in India during the Third Plan, i.e., during 1960s. As suggested by the team of experts of the Ford Foundation in its report “India’s Crisis of Food and Steps to Meet it” in 1959 the Government decided to shift the strategy followed in agricultural sector of the country.

Thus, the traditional agricultural practices followed in India are gradually being replaced by modern technology and agricultural practices. This report afford Foundation suggested to introduce intensive effort for raising agricultural production and productivity in selected regions of the country through the introduction of modern inputs like fertilizers, credit, marketing facilities etc.

Accordingly, in 1960, from seven states seven districts were selected and the Government introduced a pilot project known as Intensive Area Development Programme (IADP) into those seven districts. Later on, this programme was extended to remaining states and one district from each state was selected for intensive development.

Accordingly, in 1965, 144 districts (out of 325) were selected for intensive cultivation and the programme was renamed as Intensive Agricultural Areas Programme (IAAP).

During the period of mid-1960s, Prof. Norman Borlaug of Mexico developed new high yielding varieties of wheat and accordingly various countries started to apply this new variety with much promise. Similarly, in the kharif season in 1966, India adopted High Yielding Varieties Programme (HYVP) for the first time.

This programme was adopted as a package programme as the very success of this programme depends upon adequate irrigation facilities, application of fertilizers, high yielding varieties of seeds, pesticides, insecticides etc. In this way a new technology was gradually adopted in Indian agriculture. This new strategy is also popularly known as modern agricultural technology or green revolution.

In the initial stage, HYVP along with IAAP was implemented in 1.89 million hectares of area. Gradually the coverage of the programme was enlarged and in 1995-96, total area covered by this HYVP programme was estimated 75.0 million hectares which accounted to nearly 43 per cent of the total net sown area of the country.

As the new HYV seeds require shorter duration to grow thus it paved way for the introduction of multiple cropping, i.e., to have two or even three crops throughout the year. Farmers producing wheat in Punjab, Haryana, Western Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Delhi started to demand heavily new Mexican varieties of seeds like Lerma Rojo, Sonara-64, Kalyan and PV-18.

But in case of production of rice, although new HYV varieties of seeds like TN.-l, ADT-17, Tinen-3 and IR-8 were applied but the result was not very much encouraging. Some degree of success was only achieved in respect of IR-8.

Important Features of Green Revolution:

The following are some of the important features of Green Revolution:

1. Revolutionary:

The Green revolution is considered as revolutionary in character as it is based on new technology, new ideas, new application of inputs like HYV seeds, fertilisers, irrigation water, pesticides etc. As all these were brought suddenly and spread quickly to attain dramatic results thus it is termed as revolution in green agriculture.

2. HYV Seeds:

The most important strategy followed in green revolution is the application of high yielding variety (HYV) seeds. Most of these HYV seeds are or dwarf variety (shorter stature) and matures in a shorter period of time and can be useful where sufficient and assured water supply is available. These seeds also require four to ten time more of fertilisers than that of traditional variety.

3. Confined to Wheat Revolution:

Green revolution has been largely confined to Wheat crop neglecting the other crops. Green revolution was first introduced to wheat cultivation in those areas where sample quantity of water was available throughout the year through irrigation. Presently 90 per cent of land engaged in wheat cultivation is benefitted from this new agricultural strategy.

Most of the HYV seeds are related to wheat crop and major portion of chemical fertiliser are also used in wheat cultivation. Therefore, green revolution can be largely considered as wheat revolution.

4. Narrow Spread:

The area covered through green revolution was initially very narrow as it was very much confined to Punjab, Haryana and Western Uttar Pradesh only. It is only in recent years that coverage of green revolution is gradually being extended to other states like West Bengal, Assam, Kerala and other southern states.

Arguments in Favour of New Strategy in India:

The introduction of new agricultural strategy in India has certain arguments in its favour. These are as follows:

Firstly, India being a vast agricultural country the adoption of intensive approach is the only way to make a breakthrough in the agricultural sector within the shortest possible time.

Secondly, considering the food crisis faced by the country during 1960s it was quite necessary to adopt this new strategy for meeting the growing requirement of food in our country.

Thirdly, as the introduction of HYVP programme has been able to raise the agricultural productivity significantly, thus this new agricultural strategy is economically justified.

Fourthly, as the agricultural inputs required for the adoption of new strategy is scarce thus it would be quite beneficial to adopt this strategy in a selective way only on some promising areas so as to reap maximum benefit from intensive cultivation.

Fifthly, adoption of new strategy has its spread effect. Reaping a good yield through HYVP would induce the other farmers to adopt this new technique. Thus due to its spread effect the overall productivity of Indian agriculture would rise.

Lastly, increased agricultural productivity through the adoption of new strategy will have its secondary and tertiary effects. As the increased production of food through HYVP would reduce food imports and thus release scarce foreign exchange for other purposes.

Moreover, increased production of commercial crops would also lead to expansion of agro-based industries in the country, especially in the rural areas.

Achievements of the New Agricultural Strategy:

Let us now turn our analysis towards the achievement of new agricultural strategy adopted in India. The most important achievement of new strategy is the substantial increase in the production of major cereals like rice and wheat. Table 3.3 shows increase in the production of food crops since 1960-61.

Progress in Food grains Production:

The Table 3.3 reveals that the production of rice has increased from 35 million tons in 1960- 61 to 54 million tons in 1980-81 and then to 99.2 million tons in 2008-2009, showing a major break-through in its production. The yield per hectare has also improved from 1013 kgs in 1960 to 2,186 kg in 2008-09.

Again, the production of wheat has also increased significantly from 11 million tons in 1950-51 to 36 million tons in 1980-81 and then to 80.6 million tons in 2008-09. During this period, the yield per hectare also increased from 850 kgs to 2,891 kgs per hectare which shows that the yield rate has increased by 240 per cent during the last five decades. All these improvements resulted from the adoption of new agricultural strategy in the production of wheat and rice.

Total production of food grains in India has been facing wide fluctuations due to vagaries of monsoons. In spite of these fluctuations, total production of food grains rose from 82 million tonnes in 1960-61 to 130 million tonnes in 1980-81 and then to 213.5 million tonnes in 2003-04 and then increased to 233.9 million tonnes in 2008-09.

The new agricultural strategy was very much restricted to the production of food-grains mostly wheat and rice. Thus, the commercial crops like sugarcane, cotton, jute, oilseeds could not achieve a significant increase in its production.

Production of Cash Crops in India:

The green revolution was very much confined to mainly wheat production and its achievements in respect of other food crops and cash crops were not at all significant.

Weaknesses of the New Strategy:

The following are some of the basic weaknesses of new agricultural strategy:

(a) Adoption of new agricultural strategy through IADP and HYVP led to the growth of capitalist farming in Indian agriculture as the adoption of these programmes were very much restricted among the big farmers, necessitating a heavy amount of investment.

(b) The new agricultural strategy failed to recognise the need for institutional reforms in Indian agriculture.

(c) Green revolution has widened the disparity in income among the rural population.

(d) New agricultural strategy along-with increased mechanization of agriculture has created a problem of labour displacement.

(e) Green revolution widened the inter-regional disparities in farm production and income.

(f) Green revolution has certain undesirable social consequences arising from incapacitation due to accidents and acute poisoning from the use of pesticides.

Second Green Revolution in India:

Considering the limitations of first green revolution in India, the Government of India is now planning to introduce “Second Green Revolution” in the country with the objective of attaining food and nutritional security of the people while at the same time augmenting farm incomes and employment through this new approach.

This new approach would include introduction of “New Deal” to reverse decline in farm investment through increased funds for agricultural research, irrigation and wasteland development.

Prime Minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh while inaugurating the New Delhi office of International Food Policy Research Institute observed that, “Our government will be launching a National Horticulture Mission that is aimed, in part, at stimulating the second green revolution in the range of new crops and commodities.”

The Government is of the view that with more advances in science, and technology in areas such as biotechnology coming from the private sector, it was important to ensure availability of these products to the poor farmers.

Prime Minister Mr. Singh argued, “The challenge is how to encourage this creativity, this innovativeness and at the same time to ensure that new products and new processes will be far affordable for the vast majority of farmers who live on the edges of subsistence.”

Thus, under the present circumstances, it can be rightly said that new cutting-edge technologies should be taken to the fields for enhancing productivity to make agriculture sector of the country globally competitive.

While addressing at a national workshop on “Enhancing Competitiveness of Indian Agriculture” on 7th April, 2005 at New Delhi, Agriculture Minister Mr. Sharad Pawar observed “There is a big challenge before us. We have to adopt new technologies and familiarise them to the farming community. With 60 per cent more arable land, India produces less than half the quantity of food grains grown by China.”

Even the Brazilian yields of black peppers, originally imported from India, are six times higher than India utilizing the same variety. This simply shows that India is lagging far behind in raising productivity of agriculture.

The Economic Survey, 2006-07 while pointing out the weaknesses of agriculture in India observed, “The Structural Weaknesses of the agriculture sector reflected in low level of public investment, exhaustion of the yield potential of new high yielding varieties of wheat and rice, unbalanced fertilizer use, low seeds replacement rate, an inadequate incentive system and post harvest value addition were manifest in the lack luster agricultural growth during the new millennium.”

The Economic Survey, 2006-07 further observes, “The urgent need for taking agriculture to a higher trajectory of 4 per cent annual growth can be met only with improvement in the scale as well as quality of agricultural reforms undertaken by the various states and agencies at the various levels. These reforms must aim at efficient use of resources and conservation of soil, water and ecology on a sustainable basis and in a holistic framework. Such a holistic framework must incorporate financing of rural infrastructure such as water, roads and power.”

It is also true that today unfortunately the green revolution is a distant memory and its impact has also certainly ebbed. Therefore, it is essential to revisit the problems of the agricultural sector and address the cry of anguish that we hear from farmers from different directions of the country.

There is a strong argument for high agricultural investment, especially irrigation, which has large externalities even if it requires a scaling down of other subsidies and reordering the priorities.

The Approach Paper to the Eleventh Plan has rightly highlighted a holistic framework and suggests the strategy to raise agricultural output:

(a) Doubling the rate of growth of irrigated area;

(b)Improving water management, rain water harvesting and watershed development;

(c) Reclaiming degraded land and focusing on soil quality;

(d) Bridging the knowledge gap through effective extension;

(e) diversifying into high value outputs, fruits, vegetables, flowers, herbs and spices, medicinal plants, bamboo, bio-diesel, but with adequate measures to ensure food security;

(f) Promoting animal husbandry and fishery;

(g) Providing easy access to credit at affordable rates; and

(h) Refocusing on land reforms issues. National Commission on Farmers has already laid foundation for such a framework.

Outlining the above eight-point strategy for realizing second green revolution, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh recently observed that there was a need to improve farm management practices to enhance productivity. This also requires improvement in soil health, water conservation, credit delivery system and application of science to animal husbandry to achieve the second green revolution.

There should also be a sharper focus on strategic research in plant technology. Moreover, Indian agriculture at present needs new investments and a new wave of entrepreneurship in order to utilize its extensive potential.

However, the formulation of programmes and their implementation in different states must be based on unique regional contexts incorporating agro-climatic conditions; and availability of appropriate research and development (R & D) which is to be backed by timely and adequate extension and finance.

Moreover, R&D has to focus on areas such as rain-fed and drought from areas; crops such as drought resistant and amenable to biotechnological applications; and also on biotechnology which has huge growth as well as exponential under the present context.

In July 2006, the government initiated the National Agricultural Innovation Project (NAIP) with a provision of Rs. 1,125 crore (250 million dollar) for fine tuning agricultural research in the country. This six-yearly project is likely to enhance livelihood security in partnership mode with farmers’ groups, panchayati raj institutions and private sector which would go a long way in strengthening basic and strategic research in frontier agricultural research.

The project (NAIP) would have four components including one in which ICAR would be the catalysing agent for the management of change in the Indian national agricultural system. The other components of the project would be research in production and consumption systems, research on sustainable rural livelihood security and basic and strategic research in frontier areas of agricultural sciences.

The present WTO trade regime has changed rules of the game and the country needs to work hard to bring the benefits of changing made environment to the farmers so as to integrate domestic farm sector with the rest of the world. The processing of agricultural produce has wider options.

Processing can multiply the export value of farm produce and can open up vast international markets. India currently processes less than two per cent of its agricultural produce compared with 30 per cent in Brazil, 70 per cent in USA and 82 per cent in Malaysia.

Under this present move, the private-public partnership would play a major role in the success of the second Green Revolution in the country. Mr. Singh observed in this connection, “We have to promote greater public-private partnership in the days and months to come for bringing in an agrarian revolution.”

As a part of its programme, the Government of India, as per its NCMP, will play focused attention on the overall development of horticulture in the country by launching a National Horticulture Mission. Although it was announced in the last budget (2004-05), the Union Budget, 2005-06 has allocated Rs. 630 crore for the Mission for doubling horticulture production in the country by 2011- 12.

The Mission will ensure an end-to-end approach having backward and forward linkages covering research, production, post-harvest-management, processing and marketing, under one umbrella, in an integrated manner.

Planning Commission is considering undertaking a Food and Nutrition Security Programme to focus on achieving adequate nutrition levels among pregnant women and other people both in the urban and rural areas along-with National Food-for-work programme. The government is devoting as much as Rs. 40,000 crore to various social programmes including mid-day meal scheme and the Antyodaya Anna Yojana in recent years.

The Union Budget, 2010-11, in its four-pronged strategy for agricultural growth has undertaken a strategy to extend green revolution to the eastern region of the country comprising Bihar, Chattisgarh, Jharkhand, Eastern UP, West Bengal and Orissa with the active involvement of Gram Sabhas and the farming families. The budget has also earmarked Rs. 400 crore for this initiative.

The budget has also proposed to organise 60,000 “pulses and oilseed villages” in rain-fed areas during 2010-11 and provide an integrated intervention for water harvesting, watershed management and soil health, to enhance the productivity of the dry land farming areas. The budget provided Rs. 300 crore for this purpose and this will be an integral part of Rashtriya Krishi Vikash Yojana.

Unfortunately, the first green revolution of India was very much dependent on micro irrigation based on underground water resources. This shows lack of farsightedness on our part. As a result, the water table at the underground level has gone down seriously which has made the minor irrigation system ineffective in most green revolution infested states like Punjab, Haryana, Western Uttar Pradesh etc.

Thus it is high time that our country should not depend too much on underground water resources and instead the country and its people should try to follow the policy of water conservation and rain water harvesting by rejuvenating the ponds, wells and water bodies. The success of the second green revolution would depend very much on this new strategy which would make it sustainable and make the green revolution really green.

Second Green Revolution and the Agreements of National Commission on Farmers:

As a Chairman of the National Commission on Farmers Dr. M.S. Swaminathan, the main architect of the first green revolution of India, listed five components of Agricultural renewal. These five components as suggested by the commission include—soil health enhancement; water harvesting and sustainable and more equitable use of water; getting access to affordable credit and crop insurance as well as life insurance reform; attaining development and dissemination of appropriate technologies and improved opportunities, and creating infrastructure and regulation for viable marketing of agricultural produce.

These components suggested by the commission are considered very important for proceeding towards the second green revolution.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, while inaugurating the 93rd Indian Science Congress on June 3, 2006 mentioned two more important components. These include: (a) application of science and biotechnology to the improvement quality seeds and utilisation of herbal and other plants; and (b) application of science to animal husbandry for improving productivity of livestock and poultry.

While giving a call for a “Second Green Revolution”, Prime Minister Singh pointed out two main reasons why the first green revolution is out of steam.

These are:

(a) First green revolution did not benefit dry-land farming anyway; and

(b) it was also not scale-neutral and thereby only benefitted large farms and big farmers.

One more confirmation of the failure of first green revolution in improving the condition of the small and marginal farmer is available from the NSSO latest data on rural indebtedness for the period January to December, 2003 showing a rise in the level of indebtedness from 4 per cent to 27 per cent in just one year.

Taking the national figure of rural household indebtedness at Rs. 1,12,000 crore, the figure is found to be about 63 per cent of total outstanding debt of Rs. 1,77,000 crore of India.

Moreover, the average per capita monthly expenditure figure (MPCE) of farm household of Rs 503 is just higher by Rs. 135 only over the rural poverty line figure of Rs. 368 for India in 2003, which is again largely influenced by larger size farm households. This average MPCE figure is also lower the poverty line in many states like Orissa (Rs. 342), Jharkhand (Rs. 353), Chattisgarh (Rs. 379) and Bihar (Rs. 404) and it is also lower in 31 other districts already identified by the Government in the states like Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Kerala.

Failure of our first green revolution is also noticed in respect of the failure of our agricultural scientists in developing superior crop varieties with higher yield. As a consequence, the current level of our food grains production at 210 million tonnes is comparatively much lower to that of 550 million tonnes of China whose size of population in just 300 million higher than that of India.

Besides, the Commission (NCF) report is also silent on land reforms. Although presently the land reforms strategy is sidelined in India but for modernisation of agricultural practices needs the introduction of co-operative joint farming. The Kerala experiences in this respect can be utilised in other states.

By encouraging co-operative joint farming strategy, the problems of small and fragmented holdings of 93 per cent holdings of the country can be solved which can go a long way in improving the economic condition of small and marginal farmers of the country.

While discussing on the sidelines of 97th Indian Science Congress held at Thiruvananthapuram. Dr. M.S. Swaminathan has warned that the country would face a food crisis if agriculture and farmers were ignored. He observed “We are on the verge of a disaster. We will be in serious difficulty if food productivity is not increased and farming is neglected. The future belongs to nations with grains. The current food inflation is frightening. If pulses, potatoes and onions are beyond the purchasing capacity of the majority malnourishment will be a painful result.”

Dr. Swaminathan urged the government to implement the recommendations of the National Commission on Farmers. As the recommendations are aimed at ushering in the second green revolution in the country, the government should immediately act upon them to overcome the serious crisis we are facing on the food front.

The government should act upon three major recommendations—”It should change compensation laws as farmers do not have pay commissions like the sixth pay panel; attract youth to farming and amend the Women Farmers Entitlement Act to allow Women avail bank loans without their land as a collateral security.”

Thus it is observed that despite the unprecedented price rise, suicides by farmers and widening demand- supply gap, the government and political parties had failed to act seriously upon the recommendations made by the commission.

Finally, as the approach paper of the Eleventh Plan, emphasised on the promotion of ‘Inclusive Growth’ thus by adopting the reports of National Commission on Farmers, the Second Green Revolution should try to meet the problems of small and marginal farmers in a specific manner for providing income security to a large section of rural households.

While implementing the Second Green Revolution process, the small and marginal farmers could be given its importance and for treated as partners of development instead of a mere beneficiary of some government schemes or programmes.

Key Takeaways:

1) This sector provides approximately 52 percent of the total number of jobs available in India and contributes around 18.1 percent to the GDP. Agriculture is the only means of living for almost two-thirds of the employed class in India.

2) The Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Ministry of Agriculture (DESMOA) is responsible for the collection, (a) weekly and daily wholesale prices, (b) retail prices of essential commodities, (c) farm harvest prices.

3) In India the growth in gross area under all crops has increased from 122 million hectares in 1949-50 to 151 million hectares in 1964-65 and then it increased to 168.4 million hectares in 2008- 09.

4) Again, during the post-green revolution period (1965-2009), the average yield per hectare in respect of rice and wheat has again increased to 21.86 quintals and 28.91 quintals respectively showing a considerable annual growth rate of 3.4 per cent in respect of wheat and 2.3 per cent in respect of rice.

5) In India, total agricultural production has been increasing with the combined effect of growth in total cultivated areas and increases in the average yield per hectare of the various crops.

6) In the pre-green revolution period, the growth of output has mainly contributed to the growth or expansion in area but in the post-green revolution period, improvement in agricultural productivity arising from the adoption of modern techniques has contributed to growth in output.

7) In-spite of adopting modern technology, the growth rate in output, excepting wheat could not maintain a steady level.

8) During the post-green revolution period the growth rate in output was comparatively lower than the first annual growth rate in food grains and was maintained at the level of 2.7 per cent in the second period.

The Industrial Policy of 1948 in India:

Industrial Policy Resolution of April, 1948 classified industries into four categories, which are as follows:

1. Classification:

(i) Defence and strategic industries such as manufacture of arms and ammunition, production and control of atomic energy and ownership and management of railways were to be the exclusive monopoly of the Central Government.

(ii) In the case of basic and key industries such as coal, iron and steel, aircraft manufacture, ship building etc. all new units were to be set-up by the state while the old units were to continue to be run by the private entrepreneurs for the next ten years when the question of their nationalisation was to be decided.

(iii) Some industries were to remain in private ownership but subject to overall regulation and control by the government. Such industries included automobiles and tractors, sugar, cement, cotton and woollen textiles etc.

(iv) Rest of the industries were to remain with the private sector where government was to exercise only an overall general control.

2. Policy towards Foreign Capital:

The Industrial Policy 1948 made it clear that the Government will welcome foreign capital in India provided such capital comes without any strings or conditions attached to such foreign investments. It also emphasized that foreign capital will be allowed in joint participation with Indian capital and that the majority in management and control will remain in Indian hands.

3. Role of Cottage and Small-Scale Industries:

The Industrial Policy 1948 emphasised the role of cottage and small-scale industries in economic development. It sought to provide encouragement to these industries in India’s industrial development programmes because these industries make use of local resources and provide larger employment opportunities.

The Industrial Policy of 1948 thus laid down the foundation of a mixed economy wherein the public sector (the state) and the private sector were to co-exist and work in their demarcated areas.

The Industrial Policy of 1956:

A comprehensive industrial policy was formulated in 1956. It has following objectives:

(i) Development of machine-building industries.

(ii) Increase in rate of industrial development.

(iii) Reduction of income and wealth inequalities.

Main Features of 1956 Policy:

The following are the features of this policy:

(i) Categories of Industries: Large scale industries have been divided into 3 categories.

(a) Public Sector: Under Schedule A, 17 industries were included. These industries were arms and ammunition, atomic energy, iron and steel, heavy machinery, mineral oil, coal etc.

(b) Public-cum-private sector: Under Schedule B, 12 industries were included. Industry will be state owned but private sector can also establish industry. Industries like aluminium, machine tools, drugs, chemical fertilizer, road and sea transport, mines and minerals were included.

(c) Private sector: Under Schedule C, all remaining industries not covered in A and B Schedule were included. These industries will be established by private sector.

(ii) Cottage and small scale industries: Govt. will make efforts to promote cottage and small scale industries. Those industries will make use of local resources and will generate employment.

(iii) Concession to the public sector: Govt. will provide facility of power, transport and finance to Public sector units. However, Govt. will not adopt an indifferent attitude towards private sector units.

(iv) Balanced regional development: Industrially backward regions will be given priority in establishing industries. More incentives will be given to industries which will be established in these regions.

The Industrial Policy Statement 1977:

The Industrial Policy Statement 1977 was announced by Janata Government led by Morarji Desai on 23 December, 1977. This policy was later replaced by the incumbent Congress Government in 1980.

This was the first time when a non-congress government was ruling dispensation at centre. The Janata Government had a different approach and planning philosophy from Congress, and it reflected in its Industrial policy also.

Salient Features of Industrial Policy Statement 1977

Special Focus on Small−scale Industries

So far, the Industrial polices gave maximum emphasis to the large scale industries. The 1977 policy gave highest priority to the small scale and tiny industries.

For the first time, 1977 Industrial policy defined a “tiny unit” as a unit with investment in machinery and equipment up to Rs. 1 Lakh and situated in towns or villages with a population of less than 50,000 (as per 1971 census).

The policy declared to establish one District Industries Centre in each district to meet the requirement of industries within that district. It also announced the establishment of a separate cell in the Industrial Development Bank of India (now IDBI) to cater to the needs of the small industries. It emphasized more attention to marketing, standardisation, quality control etc. in small industries.

Focus on Labour−intensive Technology

In contrast with capital intensive industries, this policy emphasized on special efforts to develop small and ordinary machines and their optimal use to enhance productivity and income of the workers engaged in small and cottage industries. The role of large scale industries was kept limited to key and strategic sectors such as capital goods, iron and steel, petroleum, fertilizers, etc. It emphasized that the Big units would NOT be allowed to expand their production and instead; small and cottage industries would be encouraged to expand. Thus, the role of the large industries was redefined to compliment the role of small industries. It expanded the list of items reserved for exclusive production in the small scale sector from 180 to more than 500.

Viability of Public Sector

The policy emphasized on the viability, efficiency and profitability of the public sector units. It declared that the government will selectively take over sick industries to bear minimum possible loss; and will take immediate measures to rehabilitate and manage the units taken over.

Focus on Indigenous Technology

The policy called for use of indigenous technology as far as possible for future development of Industry. However, for sophisticated sectors, the government would buy the best available technology from abroad. This policy called for a restrictive use of foreign technology.

Focus on self-sufficiency

This policy called for minimum export and maximum possible self−sufficiency. It called for removing restrictions on those imports which are needed for development of priority industries.

Balanced Regional Development

Via this policy, the government decided that in the interest of balanced regional development; no more licences will be issued for the establishment of industries within certain limits of metropolitan cities having a population exceeding 10 lakh and in other cities having a population exceeding 5 lakh according to 1971 census.

Workers’ Participation

Policy laid emphasis on increased participation of workers in management.

Restrictions on Foreign Investments

The policy declared that the foreign investment in the “unnecessary areas” (meaning those which had no role to play in the development of the country), was prohibited. This was virtually a complete NO to the foreign investment. This policy is also remembered for a very important provision. The statement stated that foreign companies that diluted their foreign equity up to 40 per cent under Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA) 1973 were to be treated at par with the Indian companies. Companies like Coca Cola and IBM did not comply with the provisions and Industry Minister George Fernandez threw the Coke and IBM out of India.

The Industrial Policy Statement 1991

On July 24, 1991, Government of India announced its new industrial policy with an aim to correct the distortion and weakness of the Industrial Structure of the country that had developed in 4 decades; raise industrial efficiency to the international level; and accelerate industrial growth.

Salient Features

We can study the features of the new industrial policy 1991 under different heads as follows:

Government Monopoly

The number of industries reserved for public sector was reduced from 17 (as per 1956 policy) to only 8 industries viz. Arms and Ammunition, Atomic Energy, Coal, Mineral Oil, Mining of Iron Ore, Manganese Ore, Gold, Silver, Mining of Copper, Lead, Zinc, Atomic Minerals and Railways.

Current Position

Currently only two categories from the above viz. atomic energy and Railways are reserved for public sector. Further, Atomic minerals come within the purview of Atomic Energy Act. Government of India does not grant license to the private sector for mining of atomic minerals and mineral sand also. However, for mining of minerals present in beach sand deposits, the state governments can grant license to private parties subject to prior consent of the Department of Atomic Energy. There have been proposals to open the atomic energy sector for the private sector, but so far it has not been done.

Further, the policy had implied threat of closure of sick public sector enterprises to increase efficiency of the public sector.

Industrial Licensing Policy

This policy abolished Industrial licensing for all industries except for a short list of 18 industries. This list of 18 industries was further pruned in 1999 whereby the number reduced to six industries viz. drugs and pharmaceuticals, hazardous chemicals, explosives such as gunpowder and detonating fuses, tobacco products, alcoholic drinks, and electronic, aerospace and defence equipment. The compulsion for obtaining prior approval for setting units in metros was also removed.

However, in this policy, industries reserved for the small scale sector were continued to be so reserved.

Foreign Investment and Capital

This was the first Industrial policy in which foreign companies were allowed to have majority stake in India. In 47 high priority industries, up to 51% FDI was allowed. For export trading houses, FDI up to 74% was allowed. Today, there are numerous sectors in the economy where the government allows 100% FDI.

34 Industries were placed under the automatic approval route for direct foreign investment up to 51 percent foreign equity. It was promised that there will be no bottlenecks of any kind in this process provided that foreign equity covers the foreign exchange requirement for imported capital goods. A promise to carry out some amendments in Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (1973) was also made. (The act was later replaced by FEMA in 1999)

NRIs were allowed to 100% equity investments on non-repatriation basis in all activities except the negative list.

A provision was made that in cases where imported capital goods are required, automatic clearance is given, provided there is foreign exchange availability is ensured through foreign equity.

The government also established a special empowered board called Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB) to negotiate with international firms and approve FDI in selected areas.

Foreign Technology Agreements

Automatic permission was given for foreign technology agreements in high priority industries up to a lump sum payment of Rs. 1 crore, 5% royalty for domestic sales and 8% for exports, subject to total payment of 8% of sales over a 10 year period from date of agreement or 7 years from commencement of production. Further, the government eased hiring of foreign technicians.

Review in Public Sector Investments

A promise was made to review the portfolio of public sector investments with a view to focus the public sector on strategic, high-tech and essential infrastructure. This indicated a disinvestment of the public sector. The PSUs which were chronically sick and which are unlikely to be turned around were to be referred to the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR). It was promised that Boards of public sector companies would be made more professional and given greater powers.

Amendments to MRTP Act

The MRTP Act will be amended to remove the threshold limits of assets in respect of MRTP companies and dominant undertakings. This eliminates the requirement of prior approval of the Central Government for establishment of new undertakings, expansion of undertakings, merger, amalgamation and takeover and appointment of Directors under certain circumstances. The MRTP Limit for MRTP companies was made Rs. 100 Crore. Currently, MRTP act is replaced by Competition Act 2002.

Definition of Tiny Sector

The definition of Tiny Unit was changed as a unit having an investment limit of Less than Rs. 5 Lakh.

National Renewal Fund to provide safety net for labourers

Via this policy, the Government announced to establish a National Renewal Fund (NRF) to provide a social safety net to the labour. This fund was established in 1992 and two schemes were brought under this- first Voluntary Retirement Scheme (CRS) and another re-training scheme for rationalised workers in organised sector. The fund monies would be used to make payments under these two schemes. This fund was later abolished in 2000.

Salient Features

We can study the features of the new industrial policy 1991 under different heads as follows:

Government Monopoly

The number of industries reserved for the public sector was reduced from 17 (as per 1956 policy) to only 8 industries viz. Arms and Ammunition, Atomic Energy, Coal, Mineral Oil, Mining of Iron Ore, Manganese Ore, Gold, Silver, Mining of Copper, Lead, Zinc, Atomic Minerals and Railways.

Current Position

Currently only two categories from the above viz. atomic energy and Railways are reserved for the public sector. Further, Atomic minerals come within the purview of Atomic Energy Act. Government of India does not grant license to the private sector for mining of atomic minerals and mineral sand also. However, for mining of minerals present in beach sand deposits, the state governments can grant licenses to private parties subject to prior consent of the Department of Atomic Energy. There have been proposals to open the atomic energy sector for the private sector, but so far it has not been done.

Further, the policy had implied threat of closure of sick public sector enterprises to increase efficiency of the public sector.

Industrial Licensing Policy

This policy abolished Industrial licensing for all industries except for a short list of 18 industries. This list of 18 industries was further pruned in 1999 whereby the number reduced to six industries viz. drugs and pharmaceuticals, hazardous chemicals, explosives such as gunpowder and detonating fuses, tobacco products, alcoholic drinks, and electronic, aerospace and defence equipment. The compulsion for obtaining prior approval for setting units in metros was also removed.

However, in this policy, industries reserved for the small-scale sector were continued to be so reserved.

Foreign Investment and Capital

This was the first Industrial policy in which foreign companies were allowed to have majority stake in India. In 47 high priority industries, up to 51% FDI was allowed. For export trading houses, FDI up to 74% was allowed. Today, there are numerous sectors in the economy where government allows 100% FDI.

34 Industries were placed under the automatic approval route for direct foreign investment up to 51 percent foreign equity. It was promised that there will be no bottlenecks of any kind in this process provided that foreign equity covers the foreign exchange requirement for imported capital goods. A promise to carry out some amendments in Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (1973) was also made. (The act was later replaced by FEMA in 1999)

NRIs were allowed to 100% equity investments on non-repatriation basis in all activities except the negative list.

A provision was made that in cases where imported capital goods are required, automatic clearance is given, provided there is foreign exchange availability is ensured through foreign equity.

The government also established a special empowered board called Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB) to negotiate with international firms and approve FDI in selected areas.

Foreign Technology Agreements

Automatic permission was given for foreign technology agreements in high priority industries up to a lump sum payment of Rs. 1 crore, 5% royalty for domestic sales and 8% for exports, subject to total payment of 8% of sales over a 10 year period from date of agreement or 7 years from commencement of production. Further, government eased hiring of foreign technicians.

Review in Public Sector Investments

A promise was made to review the portfolio of public sector investments with a view to focus the public sector on strategic, high-tech and essential infrastructure. This indicated a disinvestment of the public sector. The PSUs which were chronically sick and which are unlikely to be turned around were to be referred to the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR). It was promised that Boards of public sector companies would be made more professional and given greater powers.

Amendments to MRTP Act

The MRTP Act will be amended to remove the threshold limits of assets in respect of MRTP companies and dominant undertakings. This eliminates the requirement of prior approval of Central Government for establishment of new undertakings, expansion of undertakings, merger, amalgamation and takeover and appointment of Directors under certain circumstances. The MRTP Limit for MRTP companies was made Rs. 100 Crore. Currently, MRTP act is replaced by Competition Act 2002.

Definition of Tiny Sector

The definition of Tiny Unit was changed as a unit having an investment limit of Less than Rs. 5 Lakh.

National Renewal Fund to provide safety net for labourers

Via this policy, the Government announced to establish a National Renewal Fund (NRF) to provide a social safety net to the labour. This fund was established in 1992 and two schemes were brought under this- first Voluntary Retirement Scheme (CRS) and another re-training scheme for rationalised workers in organised sector. The fund monies would be used to make payments under these two schemes. This fund was later abolished in 2000.

Why was NRF abolished?

The NRF was established to provide relief to the workers affected by technological changes, privatisation of public sector units and closure of public sector units. Those who lost their jobs would be either paid money under the VRS scheme or will be retrained / rehabilitated. The VRS scheme was under DIPP at that time. What happened was that for around 10 years, bulk of the payments in NRF was paid for VRS only; the fund did not adequately serve the stated objective of “re-training and rehabilitation”. Further, initially the private sector was also listed as its beneficiary, but later it was felt that only the public sector should be exclusively benefitted from this fund. This fund was no more than a “golden handshake scheme”. Due to this NRF was abolished and the VRS was shifted to the Department of Public Enterprises (DPE).

Tangible outcomes of the Industrial Policy 1991

This policy made Licence, Permit and Quota Raj a thing of the past. The process of liberalization is continuing. The 1991 policy attempted to liberalise the economy by removing bureaucratic hurdles in industrial growth.

The role of the public sector was limited. Only 2 sectors were finally left reserved for the public sector. This reduced burden on the government. A process of either transforming or selling off the sick units started. The process of disinvestment in PSUs also started.

The policy provided easier entry of multinational companies, privatisation, removal of asset limits on MRTP companies, liberal licensing. All this resulted in increased competition, which led to lower prices in many goods such as electronics prices. This brought domestic as well as foreign investment in almost every sector opened to private sector.

The policy was followed by special efforts to increase exports. Concepts like Export Oriented Units (EOU), Export Processing Zones (EPZ), Agri-Export Zones (AEZ), Special Economic Zones (SEZ) and lately National Investment and Manufacturing Zones(NIMZ) emerged. All these have benefitted the export sector of the country.

Gradually, a new act was passed for MSMEs in 2006 and a separate ministry was established to look into the problems of MSMEs. Government tried to provide better access to services and finance to MSMEs.

If we were to evaluate the reform process in the Indian economy over the last two decades or so, the results have been nothing short of dramatic. Those of us who have managed businesses in India before the 1990s realise this only too well. The abolition of industrial licensing, dismantling of price controls, dilution of reservations for small-scale industries and virtual abolition of the monopolies law, relaxation of restrictions on foreign investment, lowering of corporate and personal tax rates, removal of restrictions on managerial remuneration, etc. were very bold steps, all of which have enabled industry to blossom. Today’s younger generation of business managers cannot even believe that we had such an array of restrictions and handicaps.

Key Takeaways:

The following are the features of this policy:

(a) Public Sector: Under Schedule A, 17 industries were included. These industries were arms and ammunition, atomic energy, iron and steel, heavy machinery, mineral oil, coal etc.

(b) Public-cum-private sector: Under Schedule B, 12 industries were included. Industry will be state owned but the private sector can also establish industry. Industries like aluminium, machine tools, drugs, chemical fertilizer, road and sea transport, mines and minerals were included.

(c) Private sector: Under Schedule C, all remaining industries not covered in A and B Schedule were included. These industries will be established by the private sector.

4. The Industrial Policy Statement 1977 was announced by Janata Government led by Morarji Desai on 23 December, 1977. This policy was later replaced by the incumbent Congress Government in 1980.