Unit – 2

Money, Prices and Inflation

4.1 Money Supply: Determinants of Money Supply - Factors influencing Velocity of Circulation of Money

Determinants of money Supply

There are two theories of the determination of the money supply. According to the first view, the money supply is decided exogenously by the central bank. The second view holds that the money supply is decided endogenously by changes in the economic activities which affect people’s desire to hold currency relative to deposits, the rate of interest, etc.

Thus the determinants of money supply are both exogenous and endogenous which can be described broadly as: the minimum cash reserve ratio, the level of bank reserves, and the desire of the people to hold currency relative to deposits. The last two determinants together are called the monetary base or the high powered money.

1. The required Reserve Ratio:

The required reserve ratio (or the minimum cash reserve ratio or the reserve deposit ratio) is a vital determinant of the money supply. An increase within the required reserve ratio reduces the supply of money with commercial banks and a decrease in required reserve ratio increases the money supply.

The RRr is that the ratio of cash to current and time deposit liabilities which is determined by law. Every commercial bank is required to keep a certain percentage of these liabilities in the form of deposits with the central bank of the country. But notes or cash held by commercial banks within their tills are not included in the minimum required reserve ratio.

But the short-term assets alongside the cash are regarded as the liquid assets of a commercial bank. In India the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) has been fixed by law as a further measure to determine the money supply.

The SLR is called secondary reserve ratio in other countries while the required reserve ratio is referred to as the primary ratio. The raising of the SLR has the effect of reducing the money supply with commercial banks for lending purposes, and the lowering of the SLR tends to increase the money supply with banks for advances.

2. The level of Bank Reserves:

The level of bank reserves is another determinant of the money supply. Commercial bank reserves consist of reserves on deposits with the central bank and currency in their tills or vaults. It’s the central bank of the country that influences the reserves of commercial banks so as to determine the supply of money. The central bank requires all commercial banks to hold reserves adequate to a fixed percentage of both time and demand deposits.

These are legal minimum or required reserves. Required reserves (RR) are determined by the required reserve ratio (RRr) and the level of deposits (D) of a commercial bank RR=RR r× D. If deposits are Rs 80 lakhs and required reserve ratio is 20 percent, then the specified reserves are going to be 20% x 80=Rs 16 lakhs. If the reserve ratio is reduced to 10 per cent, the required reserves will also be reduced to Rs 8 lakhs.

Thus the higher the reserve ratio, the higher the required reserves to be kept by a bank, and vice versa. But it's the surplus reserves (ER) which are important for the determination of the money supply. Excess reserves are the difference between total reserves (TR) and required reserves (RR) ER=TR-RR. If total reserves are Rs 80 lakhs and required reserves are Rs 16 lakhs, then the excess reserves are Rs 64 lakhs (Rs 80 Lakhs – 16 lakhs).

When required reserves are reduced to Rs 8 lakhs, the excess reserves increase to Rs 72 lakhs. It’s the excess reserves of a commercial bank which influence the size of its deposit liabilities. A commercial bank advances loans equal to its excess reserves which are a crucial component of the money supply. To determine the supply of money with a commercial bank, the central bank influences its reserves by adopting open market operations and discount rate policy.

Open market operations refer to the purchase and sale of government securities and other types of assets like bills, securities, bonds, etc., both government and private within the open market. When the central bank buys or sells securities within the open market, the level of bank reserves expands or contracts.

The purchase of securities by the central bank is paid for with cheques to the holders of securities who, in turn, deposit them in commercial banks, thereby increasing the level of bank reserves. The opposite is that the case when the central bank sells securities to the public and banks which make payments to the central bank through cash and cheques, thereby reducing the level of bank reserves.

The discount rate policy affects the money supply by influencing the cost and supply of bank credit to commercial banks. The discount rate, referred to as the bank rate in India, is the rate of interest at which commercial banks borrow from the central bank. A high discount rate means commercial banks get less amount by selling securities to the central bank.

The commercial banks, in turn, raise their lending rates to the public, thereby making advances dearer for them. Thus there'll be contraction of credit and the level of economic bank reserves. Opposite is that the case when the bank rate is lowered. It tends to expand credit and the consequent bank reserves.

It should be noted that commercial bank reserves are affected significantly only when open market operations and discount rate policy supplement one another. Otherwise, their effectiveness as determinants of bank reserves and consequently of money supply is limited.

3. Public’s Desire to hold Currency and Deposits:

People’s desire to hold currency (or cash) relative to deposit in commercial banks also determines the money supply. If people are within the habit of keeping less in cash and more in deposits with the commercial banks, the money supply are going to be large.

This is because banks can create more money with larger deposits. On the contrary, if people don't have banking habits and prefers to stay their money holdings in cash, credit creation by banks will be less and therefore the funds will be at a low level.

4. High Powered Money and the Money Multiplier:

The current practice is to explain the determinants of the money supply in terms of the monetary base or high-powered money. High-powered money is the sum of commercial bank reserves and currency (notes and coins) held by the general public. High-powered money is the base for the expansion of bank deposits and creation of the money supply. The supply of money varies directly with changes within the monetary base, and inversely with the currency and reserve ratios.

5. Other Factors:

The money supply is a function not only of the high-powered money determined by the monetary authorities, but of interest rates, income and other factors. The latter factors change the proportion of money balances that the public holds as cash. Changes in commercial activity can change the behaviour of banks and therefore the public and thus affect the money supply. Hence the money supply isn't only an exogenous controllable item but also an endogenously determined item.

Velocity of Circulation

Velocity of Circulation refers to the average number of times a single unit of money changes hands in an economy during a given period of time. It also can be referred to as the velocity of money or velocity of circulation of money. It’s the frequency with which the total money supply in the economy turns over in a given period of time.

If the velocity of money is increasing, then the velocity of circulation is an indicator that transactions between individuals are occurring more frequently. A higher velocity is a sign that the same amount of money is being used for a number of transactions. A high velocity indicates a high degree of inflation.

Formula

The GDP equation is as follows:

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) = money supply x Velocity of Circulation

Therefore, the formula for velocity is that the following:

Velocity of Circulation = Gross Domestic Product (GDP) / money supply

Example

Consider the subsequent example. Allow us to assume that an economy consists of two individuals, a carpenter and a grocery shop owner. Over the course of a year, they exchange $100 to shop for goods/services from one another in only four transactions, which are as follows:

• The carpenter buys vegetables from the grocery store for $50.

• The carpenter also buys milk worth $50 from the grocery store.

• The grocer gets some repair work done from the carpenter and pays him $30.

• The grocer also gets wooden shelves constructed in his shop by the carpenter for $70.

We can observe that $200 changed hands during the year, even though initially there was only $100 within the economy. This is often because each dollar was spent on new goods and services twice a year. We will say that the velocity of circulation is 2/year.

However, only monetary transactions are considered during this situation. For instance, if the carpenter gifts something to the grocery store, it'll not be considered a transaction to be added to the calculation.

Velocity of Circulation and Money Demand

Whenever the rate of interest on financial assets is high, the desire to hold money falls as people attempt to exchange it for other goods or financial assets. As a result, the velocity of circulation rises. Hence, when the cash demand is low, the velocity will be high. Conversely, when the opportunity cost/alternate cost is low, money demand is high and therefore the velocity of circulation is low.

Factors affecting the velocity of Circulation

• Money Supply – money supply and therefore the velocity of money are inversely proportional If the money supply in an economy falls short, then the velocity of money will rise, and vice versa.

• Frequency of Transactions – because the number of transactions increases, so does the velocity of circulation.

• Regularity of Income – Regularity of income enables people to spend their money more freely, leading to a rise within the velocity of circulation.

• Payment System – it's also affected by the frequency with which labor is paid (weekly, monthly, bi-monthly) and the way fast the bills for various goods and services are settled.

• There are several other factors involved, including the value of money, the volume of trade, credit facilities available within the economy, business conditions

4.2 Demand for Money: Classical and Keynesian approaches and Keynes’ liquidity preference theory of interest - Friedman’s restatement of Demand for money

Keynes vehemently criticised the classical theory of employment for its unrealistic assumptions in his General Theory.

He attacked the classical theory on the subsequent counts:

(1) Underemployment Equilibrium:

Keynes rejected the basic classical assumption of full employment equilibrium within the economy. He considered it as unrealistic. He regarded full employment as a special situation. The general situation during a capitalist economy is one of underemployment.

This is because the capitalist society doesn't function according to Say’s law, and supply always exceeds its demand. We find millions of workers are prepared to work at the current wage rate, and even below it, but they do not find work.

Thus the existence of involuntary unemployment in capitalist economies (entirely ruled out by the classicists) proves that underemployment equilibrium may be a normal situation and full employment equilibrium is abnormal and accidental.

(2) Refutation of Say’s Law:

Keynes refuted Say’s Law of markets that supply always created its own demand. He maintained that each one income earned by the factor owners wouldn't be spent in buying products which they helped to produce.

A part of the earned income is saved and isn't automatically invested because saving and investment are distinct functions. So when all earned income isn't spent on consumption goods and some of it's saved, there leads to a deficiency of aggregate demand.

This results in general overproduction because all that's produced isn't sold. This, in turn, results in general unemployment. Thus Keynes rejected Say’s Law that supply created its own demand. Instead he argued that it had been demand that created supply. When aggregate demand rises, to fulfil that demand, firms produce more and employ more people.

(3) Self-adjustment not Possible:

Keynes didn't agree with the classical view that the laissez-faire policy was essential for an automatic and self-adjusting process of financial condition equilibrium. He pointed out that the capitalist system wasn't automatic and self-adjusting due to the non-egalitarian structure of its society. There are two principal classes, the rich and therefore the poor.

The rich possess much wealth but they do not spend the entire of it on consumption. The poor lack money to get consumption goods. Thus there's general deficiency of aggregate demand in reference to aggregate supply which results in overproduction and unemployment within the economy. This, in fact, led to the great Depression.

Had the capitalist system been automatic and self-adjusting, this could not have occurred. Keynes, therefore, advocated state intervention for adjusting supply and demand within the economy through fiscal and monetary measures.

(4) Equality of Saving and Investment through Income Changes:

The classicists believed that saving and investment were equal at the full employment level and in case of any divergence the equality was caused by the mechanism of rate of interest. Keynes held that the extent of saving depended upon the level of income and not on the rate of interest.

Similarly investment is decided not only by rate of interest but by the marginal efficiency of capital. A low rate of interest cannot increase investment if business expectations are low. If saving exceeds investment, it means people are spending less on consumption.

As a result, demand declines. There’s overproduction and fall in investment, income, employment and output. It’ll cause reduction in saving and ultimately the equality between saving and investment are going to be attained at a lower level of income. Thus it's variations in income instead of in rate of interest that bring the equality between saving and investment.

(5) Importance of Speculative Demand for Money:

The classical economists believed that money was demanded for transactions and precautionary purposes. They didn't recognise the speculative demand for money because money held for speculative purposes associated with idle balances.

But Keynes didn't agree with this view. He emphasised the importance of speculative demand for money. He acknowledged that the earning of interest from assets meant for transactions and precautionary purposes could also be very small at a low rate of interest.

But the speculative demand for money would be infinitely large at a low rate of interest. Thus the rate of interest won't fall below a particular minimum level, and therefore the speculative demand for money would become perfectly interest elastic. This is often Keynes ‘liquidity trap’ which the classicists did not analyse.

(6) Rejection of Quantity Theory of Money:

Keynes rejected the classical Quantity Theory of money on the ground that increase in money supply won't necessarily cause rise in prices. It’s not essential that people may spend all extra money. They’ll deposit it in the bank or save.

So the velocity of circulation of money (V) may slow down and not remain constant. Thus V within the equation MV = PT may vary. Moreover, an increase in money supply, may lead to increase in investment, employment and output if there are idle resources within the economy and the price level (P) might not be affected.

(7) Money not Neutral:

The classical economists regarded money as neutral. Therefore, they excluded the theory of output, employment and rate of interest from monetary theory. Consistent with them, the extent of output and employment and therefore the equilibrium rate of interest were determined by real forces.

Keynes criticised the classical view that monetary theory was break away value theory. He integrated monetary theory with value theory, and brought the idea of interest within the domain of monetary theory by regarding the rate of interest as a monetary phenomenon. He integrated the worth theory and therefore the monetary theory through the idea of output.

This he did by forging a link between the number of cash and therefore the price index via the speed of interest. As an example , when the number of cash increases, the speed of interest falls, investment increases, income and output increase, demand increases, factor costs and wages increase, relative prices increase, and ultimately the overall price index rises. Thus Keynes integrated monetary and real sectors of the economy.

(8) Refutation of Wage-Cut:

Keynes refuted the Pigovian formulation that a cut in money wage could achieve full employment in the economy. The biggest fallacy in Pigou’s analysis was that he extended the argument to the economy which was applicable to a selected industry.

Reduction in wage rate can increase employment in an industry by reducing costs and increasing demand. But the adoption of such a policy for the economy results in a reduction in employment. When there's a general wage-cut, the income of the workers is reduced. As a result, aggregate demand falls resulting in a decline in employment.

From the sensible view point also Keynes never favoured a wage cut policy. In times, workers have formed strong trade unions which resist a cut in money wage. They might resort to strikes. The resultant unrest in the economy would bring a decline in output and income. Moreover, social justice demands that wages shouldn't be cut if profits are left untouched.

(9) No Direct and Proportionate Relation between Money and Real Wages:

Keynes also didn't accept the classical view that there was a direct and proportionate relationship between money wages and real wages. Consistent with him, there's an inverse relation between the 2. When money wages fall, real wages rise and the other way around.

Therefore, a reduction within the money wage wouldn't reduce the real wage, as the classicists believed, rather it might increase it. This is often because the money wage cut will reduce cost of production and prices by more than the previous.

Thus the classical view that fall in real wages will increase employment breaks down. Keynes, however, believed that employment might be increased more easily through monetary and fiscal measures instead of by reduction in money wage. Moreover, institutional resistances to wage and price reductions are so strong that it's impossible to implement such a policy administratively.

(10) State Intervention Essential:

Keynes didn't agree with Pigou that “frictional maladjustments alone account for failure to utilise fully our productive power.” The capitalist system is such left to itself it's incapable of using productive powerfully. Therefore, state intervention is necessary.

The state may directly invest to raise the extent of economic activity or to supplement private investment. It’s going to pass legislation recognising trade unions, fixing minimum wages and providing relief to workers through social security measures.

“Therefore”, as observed by Dillard, “it is bad politics even if it should be considered good economics to object to labour unions and to liberal labour legislation.” So Keynes favoured state action to utilise fully the resources of the economy for attaining full employment.

(11) Long-Run Analysis Unrealistic:

The classicists believed within the long-run full employment equilibrium through a self-adjusting process. Keynes had no patience to wait for the long period for he believed that “In the long-run we are all dead”.

As pointed by Schumpeter, “His philosophy of life was essentially a short-term philosophy.” His analysis is confined to short-run phenomena. Unlike the classicists, he assumes tastes, habits, techniques of production, supply of labour, etc. to be constant during the short period then neglects long-run influences on demand.

Assuming consumption demand to be constant, he lays emphasis on increasing investment to get rid of unemployment. But the equilibrium level so reached is one among underemployment instead of full employment. Thus the classical theory of employment is unrealistic and is incapable of solving this day economic problems of the capitalist world.

Keynesian Theory of Employment

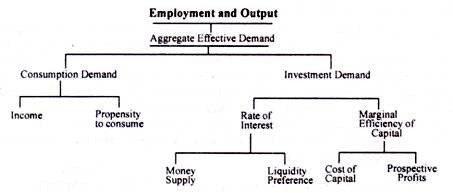

As per Keynes theory of employment, effective demand signifies the money spent on the consumption of goods and services and on investment.

The total expenditure is adequate to the national income, which is similar to the national output.

Therefore, effective demand is adequate to total expenditure as well as national income and national output.

The theory of Keynes was against the assumption of classical economists that the market forces in capitalist economy adjust themselves to achieve equilibrium. He has criticized classical theory of employment in his book. Vie General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Keynes not only criticized classical economists, but also advocated his own theory of employment.

His theory was followed by several modern economists. Keynes book was published post-Great Depression period. The great Depression had proved that market forces cannot attain equilibrium themselves; they have an external support for achieving it. This became a significant reason for accepting the Keynes view of employment.

The Keynes theory of employment was based on the view of the short run. Within the short run, he assumed that the factors of production, like capital goods, supply of labor, technology, and efficiency of labor, remain unchanged while determining the level of employment. Therefore, consistent with Keynes, level of employment depends on national income and output.

In addition, Keynes advocated that if there's an increase in national income, there would be an increase in level of employment and the other way around. Therefore, Keynes theory of employment is additionally called theory of employment determination and theory of income determination.

Principle of Effective Demand:

The main point associated with starting point of Keynes theory of employment is that the principle of effective demand. Keynes propounded that the extent of employment within the short run depends on the aggregate effective demand of products and services.

According to him, a rise in the aggregate effective demand would increase the level of employment and vice-versa. Total employment of a country are often determined with the help of total demand of the country. A decline in total effective demand would result in unemployment.

As per Keynes theory of employment, effective demand signifies the money spent on the consumption of goods and services and on investment. The entire expenditure is adequate to the national income, which is like the national output. Therefore, effective demand is adequate to total expenditure also as national income and national output.

The effective demand is often expressed as follows:

Effective demand = national income = National Output

Therefore effective demand affects employment level of a country, national income, and national output. It declines because of the mismatch of income and consumption and this decline cause unemployment.

With the increase in the national income the consumption rate also increases, but the rise in consumption rate is comparatively low as compared to the increase in national income. Low consumption rate leads to a decline in effective demand.

Therefore, the gap between the income and consumption rate should be reduced by increasing the number of investment opportunities. Consequently, effective demand also increases, which further helps in reducing unemployment and bringing full employment condition.

Moreover, effective demand refers to the total expenditure of an economy at a specific employment level. The total equal to the total supply price of economy (cost of production of products and services) at a precise level of employment. Therefore, effective demand refers to the demand of consumption and investment of an economy.

Determination of Effective Demand:

Keynes has used two key terms, namely, aggregate demand price and aggregate supply price, for determining effective demand. Aggregate demand price and aggregate supply price together contribute to determine effective demand, which further helps in estimating the extent of employment of an economy at a specific period of time.

In an economy, the employment level depends on the number of workers that are employed, in order that maximum profit are often drawn. Therefore, the employment level of an economy depends on the choices of organizations associated with hiring of employee and placing them.

The level of employment is often determined with the assistance of aggregate supply price and aggregate demand price. Let us study these two concepts in detail.

Aggregate Supply Price:

Aggregate supply price refers to the total amount of money that all organizations in an economy should receive from the sale of output produced by employing a particular number of workers. In simpler words, aggregate supply price is that the cost of production of products and services at a specific level of employment.

It is the total amount of money paid by organizations to the different factors of production involved within the production of output. Therefore, organizations would not employ the factors of production until they will recover the cost of production incurred for employing them.

A certain minimum amount of price is required for inducing employers to offer a particular amount of employment. According to Dillard, “This minimum price or proceeds, which can just induce employment on a given scale, is named the mixture supply price of that amount of employment.”

If a corporation doesn't get an adequate price so that cost of production is covered, then it employs less number of workers. Therefore the aggregate supply price varies consistent with different number of workers employed. So, aggregate supply price schedule Id Tut can be prepared as per the total number of workers employed.

Aggregate supply price schedule is a schedule of minimum price required to induce the different quantities of employment. Thus, higher the price required to induce the various quantities of employment, greater the extent of employment would be. Therefore, the slope of the aggregate supply curve is upward to the right.

Aggregate Demand Price:

Aggregate demand price is different from demand for products of individual organizations and industries. The demand for individual organizations or industries refers to a schedule of quantity purchased at different levels of price of one product.

On the hand, aggregate demand price is that the total amount of money that a company expects to receive from the sale of output produced by a particular number of workers. In other words, the mixture demand price signifies the expected sale receipts received by the organization by employing a particular number of workers.

Aggregate demand price schedule refers to the schedule of expected earnings by selling the product at different level of employment Mo higher the level of employment, greater the level of output would be.

Consequently, the rise within the employment level would increase the mixture demand price. Thus, the slope of aggregate demand curve would be upward to the right. However, the individual demand curve slopes downward.

The basic difference between the aggregate supply price and aggregate demand price should be analyzed carefully as both of them seem to be same. In aggregate supply price, organizations should receive money from the sale of output produced by employing a specific number of workers.

However, in aggregate demand price, organizations expect to receive from the sale of output produced by a particular number of workers. Therefore, in aggregate supply price, the amount of money is the necessary amount that ought to be received by the organization, while in aggregate demand price the amount of money may or might not be received.

Determination of Equilibrium Level of Employment:

The aggregate demand price and aggregate supply price help in determining the equilibrium level of employment.

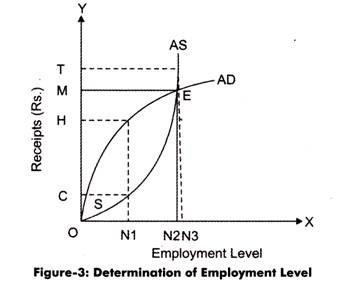

The aggregate demand (AD) and aggregate supply (AS) curve are used for determining equilibrium level of employment, as shown in Figure-3:

In Figure-3, AD represents the aggregate demand curve, while AS represents the aggregate supply curve. It are often interpreted from Figure-3 that although the aggregate demand and aggregate supply curve are moving in a similar direction, but they're not alike. There are different aggregate demand price and aggregate supply price for different levels of employment.

For example, in Figure-3, at AS curve, the organization would employ ON1 number of workers, once they receive OC amount of sales receipts. Similarly, just in case of AD curve, the organization would use ON1 number of workers with the expectation that they might produce OH amount of sales receipt for them.

The aggregate demand price exceeds the aggregate supply price or the other way around at some levels of employment. For instance, at ON1 employment level, the aggregate demand price (OH) is bigger than the aggregate supply price (OC). However, at certain level of employment, the mixture demand price and aggregate supply price become equal.

At this point, aggregate demand and aggregate supply curve intersect one another. This point of intersection is termed because the equilibrium level of employment. In Figure-3, point E represents the equilibrium level of employment because at now, the aggregate demand curve and aggregate supply curve intersect one another.

In Figure-3, initially, there's a slow movement within the AS curve, but after a certain point of time it shows a sharp rise. This implies that when a number of workers increases initially, the cost incurred for production also increases but at a slow rate. However, when the amount of sales receipt increases, the organization starts employing more and more workers. In Figure-3, the ON1 numbers of workers are employed, when OT amount of sales receipts are received by the organization.

On the opposite hand, the AD curve shows a rapid increase initially, but after a while it gets flattened. This suggests that the expected sales receipts increase with a rise in the number of workers. As a result, the expectations of the organization to earn more profit increase. As a result, the organization start employing more workers. However, after a precise level, the rise in employment level wouldn't show a rise in the amount of sales receipts.

In Figure-3, before reaching the utilization level of ON2, the employment level keeps on increasing because the organizations want to higher more and more workers to urge the maximum profit. However, when the employment level crosses the ON21 level, the AD curve is below the AS curve, which shows that the aggregate supply price exceeds the mixture demand price. As a result, the organization would start incurring losses; therefore would reduce the employment rate.

Thus, the economy would be in equilibrium when the aggregate supply price and aggregate demand price become equal. In other words, equilibrium is achieved when the amount of sales receipt necessary and therefore the amount of sales receipt expected to be received by the organization at a specified level of employment are equal.

Keynes in his A Tract on Monetary Reform (1923) gave his Real Balances Quantity Equation as an improvement over the opposite Cambridge equations. Consistent with him, people always want to have some purchasing power to finance their day to day transactions.

The amount of purchasing power (or demand for money) depends partly on their tastes and habits, and partly on their wealth. Given the tastes, habits, and wealth of the people, their desire to carry money is given. This demand for money is measured by consumption units. A consumption unit is expressed as a basket of standard articles of consumption or other objects of expenditure.

If k is that the number of consumption units within the form of cash, n is that the total currency in circulation, and p is that the price for consumption unit, then the equation is

n= pk

If k is constant, a proportionate increase in n (quantity of money) will cause a proportionate increase in p (price level).

This equation are often expanded by taking into account bank deposits. Let k’ be the number of consumption units in the form of bank deposits, and r the cash reserve ratio of banks, then the expanded equation is

n=p (k + rk’)

Again, if k, k’ and r are constant, p will change in exact proportion to the change in n.

Keynes regards his equation superior to other cash balances equations. The opposite equations fail to point how the worth level (p) can be regulated. Since the cash balances (k) held by the people are outside the control of the monetary authority, p are often regulated by controlling n and r. It's also possible to manage bank deposits k’ by appropriate changes within the bank rate. So p will be controlled by making appropriate changes in n, r and k’ so on offset changes in k.

4.3 Money and prices: Quantity theory of money - Fisher’s equation of exchange - Cambridge cash balance approach

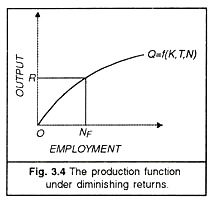

Having analysed the working of the money, capital and labour markets, we are in a position to explain the classical production function for the economy as an entire. The classical argument runs thus: As employment increases, total output also increases till full employment is readied. But when the economy is at the full employment level, total output becomes stable. Thus given the stock of capital, technological knowledge and resources, a price is relation exists between total output and therefore the amount of employment.

Total output is an increasing function of the number of workers. The economy’s short run production function is shown in Figure 3.4 as or curve which is labelled as Q =f (K, T, N), that is, total output 0 may be a function of the capital stock K. Of technological knowledge T, and therefore the number of workers, N.

This production function shows that within the short run the total output is an increasing function of the number of workers, given the capital stock and technological knowledge. We discover that the entire output curve continues to rise but the rate of rise in total output diminishes as more workers are employed. This suggests ‘diminishing returns’ to the utilization of labour and capital resources within the short run. Within the Figure, the entire output OR corresponds to the full employment level Nf as it comes from Fig. 3.3 (B).

The classicists believed that under normal competitive conditions full employment will be maintained without causing inflation. Perfect competition among employers to hire more workers won't bid wages above the full employment level, and there'll be no possibility of cost inflation within the highly competitive economy. Further, due to the operation of Say’s law, the full employment level of output will create aggregate demand adequate to that potential output level.

It is the increase in aggregate demand beyond potential output which causes inflation. But the mechanism of the speed of interest prevents aggregate demand from increasing beyond the potential output. We know that inflation is caused by an increase in the quantity of cash being more than what are often absorbed by the expanding output.

The competitive economy prevents this in the classical theoretical framework because an increase within the quantity of cash increases only the absolute price index and not relative prices. Hence the belief of full employment without inflation within the classical system are often considered valid for the long period. Depression and inflation are only temporary occurrences.

Complete Classical Model Summarised:

In its simplest form, the classical theory of unemployment is an analysis of output and employment within the interrelated labour, money and goods markets. We will precisely write the classical macro model through the subsequent set of equations:

(1) Q=………………… F (K, T, N) (Production function)

(2) Ns=f1 (W/P)………. Labour – Supply function

(3) Nd = f2 (W/P)……… Labour – demand function

(4) S=f3 (r)……….. Saving may be a function of the rate of interest (r)

(5) I =f4 (r)…………. Investment function

(6) S = I………… Equilibrium of the capital market

(7) MV= PT…………. The general price-level function (Quantity Theory)

(8) Ns = Nd……. The labour market equilibrium.

We take up the relevance of those equations to the figures drawn earlier. Within the labour market, the demand for labour and therefore the supply of labour determine the level of employment within the economy. Both are functions of the real wage rate (W/P). It’s the point of intersection of the demand and supply curves of labour which determines the equilibrium wage rate and therefore the level of full employment. They’re W/P and Nf respectively in Figure 3.3.

The total output, in turn, depends upon the extent of employment, given the capital stock and technological knowledge. The relation is shown by the production function Q =f (K, T,N) which relates total output OQ to Nf level of full employment in Fig. 2.4 which exactly equals Nf in Figure 3.3. Further, it's the mechanism of the rate of interest which brings about the equality of saving and investment in order that the amount of commodities demanded should remain adequate to the amount supplied at the full employment level, as shown in Figure 3.1.

Equilibrium within the money market is represented by the equation MV = PT. It explains the price level like the full employment level of output. It’s OP1 like OQ level of output in Figure 3.2 (A). Thus it can be said, that the classical model was perfectly logical, given its assumptions. The policy implication of the classical model was that the state should follow a non-intervention policy in economic affairs.

Summary

The classical economists took full employment for granted, believed within the automatic adjustment of the economy, and, therefore, felt no ought to present a correct theory of employment. Keynesian theory of employment was a reaction against the classical economics.

Keynes found that the classical economics provided no solution to the actually prevailing problem of wide-spread unemployment during the great Depression of 1930s. This led him to develop a systematic theory of employment, explaining the phenomenon of unemployment and suggesting the remedial measures.

By the classical economists, Keynes meant “the followers of Ricardo, those, that's to mention , who adopted and perfected the idea of the Ricardian economics, including (for example) J.S. Mill, Marshall, Edgeworth and Prof. Pigou.”

Propositions of Classical Theory of Employment:

The main propositions of the classical theory of employment are given below:

(i) Full employment may be a normal feature of a capitalist economy.

(ii) Full employment means absence of involuntary unemployment. Even at full employment, there may exist, voluntary unemployment, frictional unemployment, seasonal unemployment, structural unemployment or technical unemployment.

(iii) The economy attains equilibrium only at full employment.

(iv) General unemployment or general overproduction isn't possible.

(v) Under conditions of perfect completion, flexibility of wages tends to ascertain full employment. Reduction in wages can increase employment.

(vi) The govt shouldn't interfere in the automatic working of the economic system and will follow the policy of laissez faire.

(vii) People spend their entire income either on consumption or on investment.

(viii) Rate of interest flexibility establishes equality between saving and investment.

Assumptions of the Theory:

The classical theory of employment relies on the subsequent assumptions:

(i) Individuals are rational human beings and are motivated by self-interest.

(ii) Perfect competition exists both in product market and factor market.

(iii) Individuals don't suffer from money illusion.

(iv) Laissez-faire condition prevails, i.e., government doesn't interfere within the economic activities,

(v) There's closed economy which has no international trade relations,

(vi) Technique of production and business organisation don't change.

(vii) Money is simply a medium of exchange.

Assumption of Full Employment:

Classical theory is predicated on the idea of full employment of labour and other resources of the economy. The classical economists believed within the stable equilibrium at full employment level as a normal situation. If there's not financial condition within the actual life, then there's always an inclination towards full employment. Less-than-full employment is an abnormal situation which can disappear within the long run through automatic mechanism of the economic system.

The situation of full employment is according to the prevalence of certain amount of voluntary unemployment. Voluntary unemployment arises when the workers refuse to simply accept the going wage rate. Thus, by full employment, the classical economists mean the nonexistence of involuntary unemployment. Within the words of Prof. A.P. Lerner, “Full employment may be a situation in which all those that want to work at the existing rate of wage get work without any undue difficulty.”

Similarly, the classical economists also considered frictional unemployment as according to their assumption of financial condition. Frictional unemployment may be a temporary phenomenon which arises because of the imperfections within the labour market, such as, ignorance of job opportunities, immobility of labour, seasonal nature of work, shortage of raw materials, breakdowns of machinery, etc.

In short, when the classical economists assume full employment, they mean to say- (a) that involuntary unemployment doesn't exist; (b) that there's a prospect of some amount of frictional unemployment, and (c) that such frictional unemployment will disappear within the long run i.e., there's always an inclination towards full employment.

4.4 Inflation: Demand Pull Inflation and Cost Push Inflation - Effects of Inflation- Nature of inflation in a developing economy - policy measures to curb inflation- monetary policy and inflation targeting

Inflation is a quantitative measure of the speed at which the average price level of a basket of selected goods and services in an economy increases over a period of time. It’s the constant rise within the general level of prices where a unit of currency buys but it did in prior periods. Often expressed as a percentage, inflation indicates a decrease within the purchasing power of a nation’s currency.

Inflation – its concepts and causes of inflation.

According to A.C. Pigou (Cambridge University), inflation comes in existence “when money income is expanding more than in proportion to income activity”. An increase in general price level takes place when people have more money income to spend against less goods and services.

G. Crowther (British economists) brings out the meaning precisely when he says, “inflation is a state in which the value of money is falling i.e. prices rising”.

Inflation, according to Harry G. Johnson (Canadian economist), “is a sustained rise in prices”.

Paul Samuelson (American economist) defines inflation as “a rise in the general level of prices”.

According to Milton Friedman (American economists), ‘inflation is taxation without representation’.

Demand- Pull Inflation

Increase in Money Supply: When the monetary authorities increase the money supply in excess of the supply of goods and services it results in additional demand and consequent increase in price level. As Milton Friedman put it “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”.

Deficit Finance: As increase in money supply also takes place when the government resorts to deficit financing to incur the public expenditure. Deficit financing undertaken for unproductive investment or expenditure becomes purely inflationary. Even when it is used on productive activities, prices would still increase during the gestation period.

Credit Creation: Commercial banks increase the quantity of money in circulation when they advance loans through credit creation. Credit creation is similar to that of deficit financing in its effects.

Exports: Exports reduce the goods available in domestic market. Export earnings enhance the purchasing power of the exporters and others linked with export. An increase in exports would aggravate the situation by reducing the supply of goods and at the same time pushing up the demand because of additional income.

Repayment of Public Debt: Public debt is a common feature of modern governments. When such debts are repaid, people will have more income at their disposal. Additional disposable income tends to raise the demand for goods and services.

Black Money: Social and economic evils like corruption, tax evasion, smuggling and other illegal activities give rise to unaccounted (for tax payment) or black money. People with black money indulge in extravanza, affecting demand and thus the price level.

Increase in Population: The size of the population is one of the important determinants of demand in many developing countries population is large in size and still increasing. India provides an example where demand outstrips supply due to the large and increasing population.

Cost- Push Inflation

Inflation need not necessarily be due to an increase in demand but increase in cost. Increase in the prices of inputs including labour, increase in profit margin by the business firms and monopsony in factor market may push up prices as they influence the supply price.

The important cost push factors are:

Increase in wages: When prices increase due to increase in wages it is called wage-push inflation. Wages are influenced by many factors besides the demand and supply forces. Trade unions play an important role in deciding the wage rate. Strong and powerful trade unions succeed in securing higher wages for their members. Higher wages granted in the organised sector influencing the wage rate in the unorganised sector too, resulting in an increase in cost everywhere.

Increase in Material cost: Prices of materials used in producing goods constitute a significant part of the cost. Prices of the materials may increase either due to an increase in demand for these materials or independently owing to national and international developments. Increase in crude oil price till recently is an example in this context. When the prices of basis inputs like energy, cement, steel, etc. increase, the effect is felt throughout the economy. An increase in the prices of materials especially the basic inputs alters the cost structure of all goods and services. Higher the cost of production leads to upward revision of final prices.

Increase in Profit Margin: Firms operating under oligopoly or enjoying monopoly power (petroleum firms in public sector) may have ‘administered prices’ with higher profit margins. Such administered prices though imposed by few firms, have their impact on other firms too. The desire to have higher profit margins by all those who have the power to do so becomes the cause for inflationary trend.

Other factors: Cost of production may increase when input prices go up due to scarcity – natural or artificial. Natural calamities like draught or floods adversely affect supplies of raw materials thus making them dearer. Firms operating with excess capacity either because of monopolistic competitive market or any other reasons, produce at a higher cost.

Effects of Inflation:

People’s desires are inconsistent. When they act as buyers they want prices of goods and services to remain stable but as sellers they expect the prices of goods and services should go up. Such a happy outcome may arise for a few individuals; “but, when this happens, others will be getting the worst of both worlds.”

When price level goes up, there's both a gainer and a loser. To evaluate the consequence of inflation, one must identify the nature of inflation which can be anticipated and unanticipated. If inflation is anticipated, people can adjust with the new situation and costs of inflation to the society are going to be smaller.

In reality, people cannot predict accurately future events or people often make mistakes in predicting the course of inflation. In other words, inflation could also be unanticipated when people fail to regulate completely. This creates various problems.

One can study the consequences of unanticipated inflation under two broad headings:

(a) Effect on distribution of income and wealth; and

(b) Effect on economic growth.

(a) Effects of Inflation on Distribution of Income and Wealth:

During inflation, usually people experience rise in incomes. But some people gain during inflation at the expense of others. Some individuals gain because their money incomes rise sooner than the prices and some lose because prices rise more rapidly than their incomes during inflation. Thus, it redistributes income and wealth.

Though no conclusive evidence are often cited, it are often asserted that following categories of individuals are suffering from inflation differently:

(i) Creditors and debtors:

Borrowers gain and lenders lose during inflation because debts are fixed in rupee terms. When debts are repaid their real value declines by the price level increase and, hence, creditors lose. An individual may be interested in buying a house by taking loan of Rs. 7 lakh from an institution for 7 years.

The borrower now welcomes inflation since he will need to pay less in real terms than when it had been borrowed. Lender, within the process, loses since the rate of interest payable remains unaltered as per agreement. Due to inflation, the borrower is given ‘dear’ rupees, but pays back ‘cheap’ rupees. However, if in an inflation-ridden economy creditors chronically loose, it's wise to not advance loans or to pack up business.

Never does it happen. Rather, the loan-giving institution makes adequate safeguard against the erosion of real value. Above all, banks don't pay any interest on accounting but charges interest on loans.

(ii) Bond and debenture-holders:

In an economy, there are some people that live on interest income—they suffer most. Bondholders earn fixed interest income: These people suffer a reduction in real income when prices rise. In other words, the value of one’s savings decline if the rate of interest falls short of inflation rate. Similarly, beneficiaries from life assurance programmes also are hit badly by inflation since real value of savings deteriorate.

(iii) Investors:

People who put their money in shares during inflation are expected to gain since the likelihood of earning of business profit brightens. Higher profit induces owners of firm to distribute profit among investors or shareholders.

(iv) Salaried people and wage-earners:

Anyone earning a fixed income is damaged by inflation sometimes, unionised worker succeeds in raising wage rates of white-collar workers as compensation against price rise. But wage rate changes with a long time lag. In other words, wage rate increases always lag behind price increases. Naturally, inflation results in a reduction in real purchasing power of fixed income-earners.

On the opposite hand, people earning flexible incomes may gain during inflation. The nominal incomes of such people outstrip the general price rise. As a result, real incomes of this income group increase.

(v) Profit-earners, speculators and black marketers:

It is argued that profit-earners gain from inflation. Profit tends to rise during inflation. Seeing inflation, businessmen raise the costs of their products. This results in a bigger profit. Profit margin, however, might not be high when the rate of inflation climbs to a high level.

However, speculators dealing in business in essential commodities usually stand to realize by inflation. Black marketers also are benefited by inflation.

Thus, there occurs a redistribution of income and wealth. It’s said that rich becomes richer and poor becomes poorer during inflation. However, no such hard and fast generalisation can be made. It’s clear that someone wins and someone loses during inflation.

These effects of inflation may persist if inflation is unanticipated. However, the redistributive burdens of inflation on income and wealth are most likely to be minimal if inflation is anticipated by the people. With anticipated inflation, people can build up their strategies to deal with inflation.

If the annual rate of inflation in an economy is anticipated correctly people will attempt to protect them against losses resulting from inflation. Workers will demand 10 p.c. Wage increase if inflation is predicted to rise by 10 p.c.

Similarly, a percentage of inflation premium are going to be demanded by creditors from debtors. Business firms also will fix prices of their products in accordance with the anticipated price rise. Now if the entire society “learn to live with inflation”, the redistributive effect of inflation will be minimal

However, it's difficult to anticipate properly every episode of inflation. Further, even if it's anticipated it cannot be perfect. In addition, adjustment with the new expected inflationary conditions might not be possible for all categories of people. Thus, adverse redistributive effects are likely to occur.

Finally, anticipated inflation can also be costly to the society. If people’s expectation regarding future price rise become stronger they're going to hold less liquid money. Mere holding of cash balances during inflation is unwise since its real value declines. That is why people use their money balances in buying land, gold, jewellery, etc. Such investment is referred to as unproductive investment. Thus, during inflation of anticipated variety, there occurs a diversion of resources from priority to non-priority or unproductive sectors.

(b) Effect on Production and Economic Growth:

Inflation may or might not end in higher output. Below the complete employment stage, inflation features a favourable effect on production generally, profit may be a rising function of the worth level. An inflationary situation gives an incentive to businessmen to boost prices of their products so on earn higher volume of profit. Rising price and rising profit encourage firms to form larger investments.

As a result, the multiplier effect of investment will inherit operation leading to a better national output. However, such a favourable effect of inflation is going to be temporary if wages and production costs rise very rapidly.

Further, inflationary situation could also be associated with the fall in output, particularly if inflation is of the cost-push variety. Thus, there's no strict relationship between prices and output. An increase in aggregate demand will increase both prices and output, but a supply shock will raise prices and lower output.

Inflation can also lower down further production levels. It’s commonly assumed that if inflationary tendencies nurtured by experienced inflation persist in future, people will now save less and consume more. Rising saving propensities will end in lower further outputs.

One can also argue that inflation creates an air of uncertainty within the minds of business community, particularly when the rate of inflation fluctuates. Within the midst of rising inflationary trend, firms cannot accurately estimate their costs and revenues. That is, during a situation of unanticipated inflation, a great deal of risk element exists.

It is due to uncertainty of expected inflation; investors become reluctant to invest in their business and to form long-term commitments. Under the circumstance, business firms may be deterred in investing. This may adversely affect the growth performance of the economy.

However, slight dose of inflation is necessary for economic growth. Mild inflation has an encouraging effect on national output. But it's difficult to form the price rise of a creeping variety. High rate of inflation acts as a disincentive to long run economic growth. The way the hyperinflation affects economic growth is summed up here. We know that hyper-inflation discourages savings.

A fall in savings means a lower rate of capital formation. a low rate of capital formation hinders economic growth. Further, during excessive price rise, there occurs a rise in unproductive investment in real estate, gold, jewellery, etc. Above all, speculative businesses flourish during inflation resulting in artificial scarcities and, hence, further rise in prices.

Again, following hyperinflation, export earnings decline leading to a wide imbalances within the balance of payment account. Often galloping inflation leads to a ‘flight’ of capital to foreign countries since people lose confidence and faith over the monetary arrangements of the country, thereby leading to a scarcity of resources. Finally, real value of tax income also declines under the impact of hyperinflation. Government then experiences a shortfall in investible resources.

Thus economists and policymakers are unanimous regarding the risks of high price rise. But the results of hyperinflation are disastrous. Within the past, a number of the world economies (e.g., Germany after the primary war (1914-1918), Latin American countries within the 1980s) had been greatly ravaged by hyperinflation.

Nature of inflation in a developing economy

An unnecessary controversy has come to revolve around the idea whether inflation helps or hinders economic development. It’s impossible to attempt a categorical reply.

However, one thing is for certain that within the fundamental equation Y = C + I, if the level of income (Y) is to be raised, the extent of investment (I) has got to be raised [because, it's impossible to increase consumption (C) unless Y is raised]. Hence a case for inflationary finance is usually made.

The policy of ‘mild inflation’ either through public or private agencies, becomes absolutely essential for the mobilization of resources and for breaking what we call ‘vicious circle of poverty. Maurice Dobb remarks, “Inducements are necessary for large-scale movements of labour and for increased supplies of foodstuffs and raw materials to be made available by the village for the town.”

Prof. Kaldor has also acknowledged that “a slow and steady rate of inflation provides a most powerful aid to the attainment of a steady rate of economic progress.” Prof. Robertson has also favoured a policy of raising price index. Such a policy of slow and steady inflation is especially significant in underdeveloped economies, where an excellent a part of the labour force is self-employed and price incentives (through mild inflation) assume greater importance, than wage incentives (at least within the initial stages of breakthrough).

Prof. W.W. Rostow has maintained that several ‘take off processes were assisted by inflation. Within the view of Hamilton, inflation has been a strong stimulant during a large number of historical instances and will perform an identical function in underdeveloped countries. Keynes also spoke in favour of profit inflation’ in his Treatise on Money. The advocates of development through inflation hold that such a policy is fruitful for capital formation through the redistributive effects of inflation in favour of the rich class, having a better propensity to save and invest than the poor, and to divert the disguised unemployed labour to industry.

These and many other economists believe that a mild or creeping inflation is not necessarily an undesirable thing because the alternative to this is unemployment and impaired economic growth. They argue that since prices are flexible only in the upward direction in our present institutional set up, resource allocation through the price system must operate through price increases in the areas of the economy that are growing rather than through price decrease in areas that are stagnating.

They argue that the monopoly power of unions and enterprises is such that price increases are inevitable and, therefore, it's better for the authorities to not follow deflationary policies which could cause unemployment instead of a fall in price level. Thus, a light or creeping inflation helps economic development by creating favourable profit expectations amongst businessmen. Prof. Lewis feels that inflation for purpose of creating useful capital is often ultimately self-termination, since sooner or later it's likely to result in an increased supply of products to the market.

There are other economists who put forward overriding objection. They fear that inflation rather than being ‘self-destructive’ can also become ‘self-cumulative’. ‘Demand pull’ inflation, according to them, may degenerate into ‘cost-push’ inflation and may hinder instead of help economic development. They argue that the resources could be mobilized by direct measures also, without resorting to inflation. Friedman, for instance, totally disagrees with the policy of ‘development through inflation’ more so in developing economies. He does not agree with the argument that inflation will tend to stimulate development through its redistributive effects. Consistent with him, it's a mistake to consider deficit financing, or printing money, as a source of revenue distinct from taxation and borrowings.

It is useful to realize that there exists a two-way relationship between price change (inflation) and economic development. The latter affects the behaviour of prices and price changes affect the rate of economic development. Research and empirical studies haven't been ready to establish any direct or consistent correlation between the two. One study points out that “even if some consistent statistical relationship could be established between price changes and rates of economic growth, this relationship would not justify any definite conclusion about causation.”

It is impossible to say with certainty which is that the independent and which the dependent variable is. The studies have revealed no systematic relationship between price changes (inflation) and rate of growth. The relationship, if any, has been different from country to country; where the two were inversely related in Germany and Japan, they moved together in Sweden and Canada.

Despite this doubt about the exact relationship between inflation and economic growth, all evidence tends to suggest that in an underdeveloped country, which has followed a consistent policy of inflationary finance, the process of capital formation and economic growth are adversely affected. Our conclusion, therefore, is that while there seems to be some case, at least in the short- run, in favour of inflationary finance for capital formation and economic growth; a policy of continuous inflation may do more harm than good especially within the face of ineffective and infant nature of fiscal and monetary policies that are adopted in less developed countries.

It is quite obvious that no text-book approach to money and inflation in developing economies will take us nearer solution. It’s really surprising that the term ‘inflation’ has been misused even by those that should know it better! As such it's been the cause of great muddle! If words are to be used with some accuracy it would imply ‘an increase within the quantity of cash beyond the point necessary for full employment of resources. It doesn't mean merely rise in prices which has led to the fear complex and the urge to fight inflation as and when it appears without realizing its extent— and how a rise within the quantity of money is essential for full employment of resources.

To prefer stable prices to rising real income and living standards is to fall flat into the ancient ‘money illusion’— i.e., to treat the measuring rod as more important than what it measures and indeed to crucify the mankind on a cross of paper ! In modern industrial societies, full use of labour and capital equipment has not been possible without a minimum of a slow rise in prices.

The historical and empirical evidence go to support this. During the last 25 years, except in West Germany in early 1950 and in USA in early 1960, no country has been ready to achieve economic process and price stability together. Aside from the talk that goes on between Friedmanites and anti-Friedmanites on the synthetic question whether monetary or economic policy has greater effect on prices ; the least we will do is to avoid using frightful phrases like ‘fighting inflation’ and aiming at price stability because fighting inflation without appropriate incomes policy is a wild goose chase!

Measures for Controlling Inflation

Inflation is considered to be a complex situation for an economy. If inflation goes beyond a moderate rate, it can create disastrous situations for an economy; therefore is should be under control.

It is hard to control inflation by using a particular measure or instrument.

The main aim of each measure is to reduce the inflow of money in the economy or reduce the liquidity within the market.

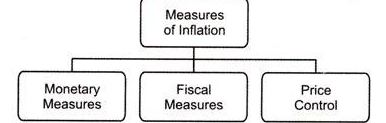

The different measures used for controlling inflation are shown in Figure-5:

The different measures (as shown in Figure) used for controlling inflation are explained below.

1. Monetary Measures:

The government of a country takes several measures and formulates policies to control economic activities. Monetary policy is one among the most commonly used measures taken by the govt to control inflation.

In monetary policy, the central bank increases rate of interest on borrowings for commercial banks. As a result, commercial banks increase their rate of interests on credit for the public. In such a situation, individuals like better to save money instead of investing in new ventures.

This would reduce money supply within the market, which, in turn, controls inflation. Aside from this, the central bank reduces the credit creation capacity of commercial banks to regulate inflation.

The monetary policy of a country involves the following:

(a) Rise in Bank Rate:

Refers to one of the most widely used measure taken by the central bank to control inflation

The bank rate is the rate at which the commercial bank gets a rediscount on loans and advances by the central bank. The increase in the bank rate leads to the rise of rate of interest on loans for the public. This results in the reduction in total spending of individuals.

The main reasons for reduction in total expenditure of individuals are as follows;

(i) Making the borrowing of money costlier:

Refers to the very fact that with the rise within the bank rate by the central bank increases the rate of interest on loans and advances by commercial banks this makes the borrowing of money expensive for general public

Consequently, individuals postpone their investment plans and wait for fall in interest rates in future. The reduction in investments results in the decreases within the total spending and helps in controlling inflation.

(ii) Creating adverse situations for businesses:

Implies that increase in bank rate has a psychological impact on some of the businesspersons they consider this example adverse for carrying out their business activities. Therefore, they reduce their spending and investment.

(iii) Increasing the propensity to save:

Refers to one of the most important reason for reduction in total expenditure of people. It’s a well-known fact that individuals generally like better to save money in inflationary conditions. As a result, the total expenditure of individuals on consumption and investment decreases.

(b) Direct Control on Credit Creation:

Constitutes the major part of monetary policy

The central bank directly reduces the credit control capacity of commercial banks by using the subsequent methods:

(i) Performing Open Market Operations (OMO):

Refers to one of the important method used by the central bank to reduce the credit creation capacity of commercial banks the central bank issues government securities to commercial banks and certain private businesses.

In this way, the cash with commercial banks would be spent on purchasing government securities. As a result, commercial bank would reduce credit supply for the general public.

(ii) Changing Reserve Ratios:

Involves increase or decrease in reserve ratios by the central bank to reduce the credit creation capacity of commercial banks for instance , when the central bank needs to reduce the credit creation capacity of commercial banks, it increases Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR). As a result, commercial banks need to keep a large amount of cash as reserve from their total deposits with the financial institution. This is able to further reduce the lending capacity of commercial banks. Consequently, the investment by individuals in an economy would also reduce.

2. Fiscal Measures:

Apart from monetary policy, the govt also uses fiscal measures to control inflation. The two main components of fiscal policy are government revenue and government expenditure. In fiscal policy, the govt. Controls inflation either by reducing private spending or by decreasing government expenditure, or by using both.

It reduces private spending by increasing taxes on private businesses. When private spending is more, the govt reduces its expenditure to regulate inflation. However, in present scenario, reducing government expenditure is not possible because there could also be certain on-going projects for social welfare that can't be postponed.

Besides this, the govt. Expenditures are essential for other areas, like defence, health, education, and law and order. In such a case, reducing private spending is more preferable rather than decreasing government expenditure. When the govt reduces private spending by increasing taxes, individuals decrease their total expenditure.

For example, if direct taxes on profits increase, the total disposable income would reduce. As a result, the total spending of people decreases, which, in turn, reduces money supply within the market. Therefore, at the time of inflation, the govt reduces its expenditure and increases taxes for dropping private spending.

3. Price Control:

Another method for ceasing inflation is preventing any further rise within the prices of goods and services. In this method, inflation is suppressed by price control, but can't be controlled for the future. In such a case, the essential inflationary pressure within the economy isn't exhibited within the form of rise in prices for a short time. Such inflation is termed as suppressed inflation.

The historical evidences have shown that control alone cannot control inflation, but only reduces the extent of inflation. For instance, at the time of wars, the govt of various countries imposed price controls to prevent any further rise within the prices. However, prices remain at peak in different economies. This was due to the rationale that inflation was persistent in different economies, which caused sharp rise in prices. Therefore, it are often said inflation can't be ceased unless its cause is determined.

Inflation targeting may be a monetary policy where the central bank sets a specific rate of inflation as its goal. The central bank does this to form you think prices will continue rising. It spurs the economy by making you buy things now before they cost more.

Most central banks use an inflation target of 22. That applies to the core rate of inflation. It takes out the effect of food and energy prices. These prices are volatile, swinging wildly from month-to-month. Monetary policy tools, on the opposite hand, are slow-acting. It takes six to 18 months before a rate of interest change impacts the economy. Central banks don't need to base slow-acting actions on indicators that move too quickly.

Inflation targeting

Inflation targeting involves using monetary policy to keep inflation close to the agreed target.

RBI and Government of India signed a Monetary Policy Framework Agreement in February 2015.

- As per terms of the agreement, the target of monetary policy framework would be primarily to maintain price stability (inflation targeting), while keeping in mind the objective of growth.

- According to the agreement, RBI would aim to contain consumer price inflation within 4% with a band of () 2% for all subsequent years.