UNIT 2

CAPITAL BUDGETING-PROJECT PLANNING & RISK ANALYSIS

The financial requirements of business can be classified as short-term and long-term financial requirements. Short-term funds are required for meeting working capital needs. It is usually required for a period up to one year. Long-term funds are required to a great extent for meeting the fixed capital requirements of the business. It is required for a period of 1 to 5 years or more. Fixed capital is required for investment in land, building, plant and machinery, vehicles and furniture etc. The long-term funds are raised by issue of shares, debentures, loans from financial institutions and banks.

Capital investment involves a cash outflow in the immediate future in anticipation of returns of a future date. The planning and control of capital expenditure is called as capital budgeting decisions. Capital budgeting is an art of finding assets that are worth more than their cost to achieve the objectives i.e. optimizing the wealth of a business enterprise. A key challenge for the companies is to identify projects which fit the objectives and promise to be profitable. Capital expenditure decisions usually involve large sums of money, long-time spans and carry some degree of risk and uncertainty. Realistic investment appraisal requires the financial evaluation of many factors such as the choice of size, type, location, timing of investments, taxation, and opportunity cost of funds available and alternative forms of financing the projects.

A Project is a scheme for investing resources. It is a proposal of something to be done, plan or scheme. Every business plan is a project. The entrepreneur has to identify an opportunity to undertake a new venture. The business opportunity can be generated through various techniques like market research observations at market places, consultation with experts and brainstorming sessions. The entrepreneur should conduct cost- benefit analysis of each and every idea. The costs can be measured in terms of resources required to implement the opportunity and the benefits can be measured in terms of sales, profits etc. Thus, a project is a business plan. It describes the future direction of the business. The entrepreneur should prepare a sound business plan in order to exploit the opportunity. A good business plan is important in determining the resources required, obtain the resources and effectively manage the business venture.

Types / Classification of Projects

There are different types of projects undertaken by the business. The important types of projects are given below:-

- Modernization Project: Modernization projects involve removal of old machines and installation of new machines in their place to cope with dynamic and competitive business environment.

- Expansion Projects: Expansion projects are undertaken to enlarge the plant capacity with a view to produce a large volume of production than the current level of production.

- Diversification Projects: Diversification project is an investment decision to set up an entirely new project which is not connected with the existing line of business.

- Balancing Projects: New plant and machinery is installed in order to remove the bottlenecks (imbalance) and to increase the capacity utilization of the total plant. In installing balancing equipment, these would be free flow in the process and uninterrupted production is ensured and there will be increase in the revenue.

- Replacement Project: Replacement of an existing asset with more economic one is a replacement project. By replacement, the operational efficiency is increased, cost of production is reduced, cost of maintenance is reduced and profitability is increased.

Following are the major Stages of Capital Budgeting Process:

- Project identification and generation:

On this stage ideas and suggestions for possible investment opportunities of enterprise resources are identified. Here the proposal for investments is generated taking into consideration the various reasons for taking up investments in a business. The reasons may be addition of a new product line or expanding the existing one. It could be a proposal to either increase the production or reduce the costs of outputs. The investment suggestions may be from inside the firm, such as from its employees, or from outside the firm, such as from a firm’s advisors.

2. Project Screening and Evaluation:

In this phase ideas and suggestions having greatest income potential are developed into complete and detailed investment plans. This step mainly involves selecting all correct criteria’s to judge the desirability of a proposal. The main object of this stage is to avoid unnecessary wastage of resources like time, money and effort. The tool of time value of money becomes useful in this step. Also the estimation of the benefits and the costs needs to be done. The total cash inflow and outflow along with the uncertainties and risks associated with the proposal has to be analyzed thoroughly and appropriate provisioning has to be done for the same.

3. Project Selection:

In the third phase, investment plans are compared, and those that appear to be in the best interest of the enterprise are selected. Here it has been checked whether the proposed investment project would add value to the firm or not. Properly defined method for the selection of a proposal for investments is not there as different businesses have different requirements.

4. Preparing the capital budget:

Once the proposal has been finalized, the different alternatives for raising or acquiring funds have to be explored by the finance team. This is called preparing the capital budget. The average cost of funds has to be reduced. A detailed procedure for periodical reports and tracking the project for the lifetime needs to be streamlined in the initial phase itself. The final approvals are based on profitability, Economic constituents, viability and market conditions.

5. The acceptance or rejection of the project:

In this phase it has been decided whether to accept or reject a project. All information, coming from the financial appraisal and qualitative results, is collected for making decisions. Managers with experience and knowledge also consider other relevant information using their routine information sources, expertise and judgments.

6. Implementation and Monitoring:

Once an investment project is accepted, then this phase involves the setting up of manufacturing facilities, project and engineering designs, negotiations and contracting, construction, and training and plant commissioning etc. Here the investment performance is monitored for any significant variations from expectations to determine if goals are being met Money is spent and thus proposal is implemented. The different responsibilities like implementing the proposals, completion of the project within the requisite time period and reduction of cost are allotted.

7. Performance review or Post-implementation audit:

This is the last phase which involves comparison of actual results with the standard ones. Post-implementation audit can provide useful feedback to project appraisal or strategy formulation. The feedback helps to identify and remove the various difficulties of the projects and for future selection and execution of the proposals.

Project analysis requires time and effort. The costs incurred in this exercise must be justified by the benefits from it. Certain projects, given their complexity and magnitude, may warrant a detailed analysis while others may call for a relatively simple analysis. Hence firms normally classify projects into different categories. Each category is then analysed somewhat differently.

While the system of classification may vary from one firm to another, the following categories are found in most classifications.

Mandatory Investment: These are expenditures required to comply with statutory requirements. Examples of such investments are pollution control equipment, medical dispensary, fire fitting equipment, clr5che in factory premises, and so on. These are often non-revenue producing investments. In analyzing such investments the focus is mainly on finding the most cost-effective way of fulfilling a given statutory need.

Replacement Projects: Firms routinely invest in equipments meant to replace Obsolete and inefficient equipments, even though they may be in a serviceable condition. The objective of such investments is to reduce costs (of labor, raw material, and power), increase yield, and improve quality. Replacement projects can be evaluated in a fairly straightforward manner, though at times the analysis may be quite detailed.

Expansion Projects: These investments are meant to increase capacity and/or widen the distribution network. Such investments call for an explicit forecast of growth. Since this can be risky and complex, expansion projects normally warrant more careful analysis than replacement projects. Decision relating to such projects is taken by the top management.

Diversification Projects: These investments are aimed at producing new products or Services or entirely new geographical areas. Often diversification projects entail substantial risks, involve large outlays, and require considerable managerial effort and attention. Given their strategic importance, such projects call for a very thorough evaluation, both quantitative and qualitative. Further, they require a significant involvement of the board of directors.

Research and Development Projects: R&D projects absorbed a very Small proportion of capital budget in most Indian companies. Things, however, are changing. Companies are now allocating mote funds to R&D projects, more so in knowledge-intensive industries. R&D projects are characterized by numerous uncertainties and typically involve sequential decision-making. Hence the standard DCF analysis is not applicable to them. Such projects are decided on the basis of managerial judgment. Firms, which rely more on quantitative methods, use decision tree analysis and option analysis to evaluate R&D projects.

Miscellaneous Projects: This is a catch-all category that includes items like interior Decoration, recreational facilities, executive aircrafts, landscaped gardens, and so on.

There is no standard approach for evaluating these projects and decisions regarding them are based on personal preferences of top management.

The rationale underlying the capital budgeting decision is efficiency. Thus, a firm must replace worn and obsolete plants and machinery, acquire fixed assets for current and new products and make strategic investment decisions. This will enable the firm to achieve its objective of maximizing profits either by way of increased revenues or cost reductions. The quality of these decisions is improved by capital budgeting. Capital budgeting decision can be of two types: (i) those which expand revenues, and (ii) those which reduce costs.

Investment Decision Affecting Revenues: Such investment decisions are expected to bring in additional revenue, thereby raising the size of the firm’s total revenue. They can be the result of either expansion of present operations or the development of new product lines. Both types of investment decisions involve acquisition of new fixed assets and are income-expansionary in nature in the case of manufacturing firms.

Investment Decisions Reducing Costs: Such decisions, by reducing costs, add to the earnings of firm. A classic example of such investment decisions is the replacement proposals when an asset wears out or becomes outdated. The firm must decide whether to continue with the existing assets or replace them. The firm evaluates the benefits from the new machine in terms of lower operating cost and the outlay that would be needed to replace the machine. An expenditure on a new machine may be quite justifiable in the light of the total cost savings that result.

A fundamental difference between the above two categories of investment decision lies in the fact that cost-reduction investment decisions are subject to less uncertainty in comparison to the revenue-affecting investment decisions. This is so because the firm has a better ‘feel’ for potential cost savings as it can examine past production and cost data. However, it is difficult to precisely estimate the revenues and costs resulting from a new product line, particularly when the firm, kflows relatively little about the same.

Typical examples of capital budgeting decisions are:

• expansion projects;

• replacement projects;

• selection among alternatives; and

• buy or lease decisions.

Good capital budgeting decisions, based on sound investment appraisal procedures, should improve the timing of capital acquisitions as well as the quality of capital acquisitions.

Investment in expansion/ modernisation is one of the main sources of economic growth, since it is required not only to increase the total capital stock of equipment and buildings, but also to employ labour in increasingly productive jobs as old plant is replaced by new.

Successful administration of capital investments by a company involves

- Generation of investment proposals

- Estimation of cash flows for the proposals

- Evaluation of cash flows

- Selection of projects based upon an acceptance criterion

- Continual reevaluation of investment projects after their acceptance

Depending upon the firm involved, investment proposals can emanate from various sources. For purposes of analysis, projects may be classified into one of five categories.

- New products or expansion of existing products

- Replacement of equipment or buildings

- Research and development

- Exploration

- Others

The fifth category comprises miscellaneous items such as the expenditure of funds to comply with certain health standards or the acquisition of a pollution-control device. For a new product, the proposal usually originates in the marketing department. On the other hand a proposal to replace a piece of equipment with a more sophisticated model usually emanates from the production area of the firm, in each case, efficient administrative procedures are needed for channeling in-

Most firms screen proposals at multiple levels of authority. For a proposal originating in the production area, the hierarchy of authority might run from (1) section chiefs to (2)plant managers to (3) the vice-president for operations to (4) a capital expenditures committee under the financial manager to (5) the president to (6) the board of directors. How high a proposal must go before it is finally approved usually depends upon its size. The greater the capital outlay, the greater the number of screens usually required. Plant managers may be able to approve moderate-sized projects on their own, but only higher levels of authority approve larger ones. Because the administrative procedures for screening investment proposals vary greatly from firm to firm, it is not possible to generalize. The best procedure will depend upon the circumstances.

The level and type of capital expenditure appear to be important to investors, as they convey information about the expected future growth of earnings. John J. McConnell and Chris J. Muscarelia test this notion with respect to the level of expenditures of a company. They find that an increase in capital-expenditure intentions, relative to prior expectations, results in increased stock returns around the time of the announcement, and vice versa for an unexpected decrease.

Estimation of cash flows is a difficult task because the future is uncertain. Operating managers with the help of finance executives should develop cash now estimates. The risk associated with cash flows should also be property handled and should be taken into account in the decision process. Estimation of cash flows requires collection and analysis of all qualitative and quantitative data, both financial and non-financial in nature. Large companies would have a management information system providing such data.

Executives in practice do not always have clarity about estimating cash flows. A large number of companies do not include additional working capital while estimating the investment project cash flows. A number of companies also mix up financial flows with operating flows. Although the companies claim to estimate cash flows on incremental basis, some of them make no adjustment for sale proceeds of existing assets while computing the project’s initial cost.

Most Indian companies choose an arbitrary period of 5 or 10 years for forecasting cash flows. This was because companies in India largely depended on government-owned financial institutions for financing their projects, and these institutions required 5 to 10 years forecasts of the project Cash flows.

The evaluation of projects should be performed by a group of experts who have no are to grind. For example, the production people may be generally interested in having the most modem type of equipments and increased production even if productivity is expected to be low and goods cannot be sold. This attitude can bias their estimates of cash flows of the proposed projects. Similarly, marketing executives may be too optimistic about the sales prospects of goods manufactured, and overestimate the benefits of a proposed new product. It is therefore, necessary to ensure that an impartial group scrutinizes projects and that objectivity is maintained in the evaluation process.

A company in practice should take all care in selecting a method or methods of investment evaluation. The criterion or criteria selected should be a true measure of evaluating if the investment is profitable (in terms of cash flows), and it should lead to the net increase in the company’s wealth (that is, its benefits should exceed its cost adjusted for time value and risk). It should also be seen that the evaluation criteria do not discriminate between the investment proposals. They should be capable of ranking projects correctly in terms of profitability. The net present value method is theoretically the most desirable criterion as it is a true measure of profitability; it generally ranks projects correctly and is consistent with the wealth maximisation criterion. In practice, however, managers’ choice may be governed by other practical considerations also.

A formal financial evaluation of proposed capital expenditures has become a common practice among companies in India. A number of companies have a formal financial evaluation of almost three-fourths of their investment rojects. Most companies subject more than 50 per cent of the projects to some kind of formal evaluation. However, projects, such as replacement or worn-out equipment, welfare and statutorily required projects below certain limits, small value items like office equipment or furniture, replacement of assets of immediate requirements, etc., are not often formally evaluated.

Methods of Evaluation

As regards the use of evaluation methods, most Indian companies, use payback criterion. In addition to payback and/or other methods, some companies also use internal rate of return (IRR) and net present (NPV) methods. A few companies use accounting rate of return (ARR) method. IRR is the second most popular technique in India.

The major reason for DCF techniques not being as popular as payback is the lack of familiarity with DCF on the part of executives. Other factors are lack of technical people and sometimes unwillingness of top management to use the DCF techniques. One large manufacturing and marketing organisation, for example, thinks that conditions of its business are such that the DCF techniques are not needed. By business conditions the company perhaps means its marketing nature, and its products being in seller’s markets. Another company feels that replacement projects are very frequent in the company, and therefore, it is not necessary to use DCF techniques for such projects.

The practice of companies in India regarding the use of evaluation criteria is similar to that in USA. A study by Schall, Sundem and Geiljsbeak (1978) showed that whereas 86 per cent of the firms used either the internal rate of return or net present value models, only 16 per cent used such discounting techniques without using the payback period or average rate of return methods. The tendency of US firms to use naive techniques as supplementary tools has also been reported in other studies. However, firms in USA have come to depend increasingly on the DCF techniques, particularly IRR. According to Rockley’s study (1973X the British companies use both DCF techniques and return on capital, sometimes in combination and sometimes solely, in their investment evaluation; the use of payback is wide-spread. A recent study by Pike shows that the use of the DCF methods has significantly increased in UK in 1992, and NPV is more popular than IRR. However, this increase has not reduced the importance of the traditional methods such as payback and return on investment. Payback continues to be employed by almost all companies.

One significant difference between practices in India and USA is that payback is used in India as a ‘primary’ method and IRRJNPV as a ‘secondary’ method, while it is just the reverse in USA. Indian managers feel that payback is a convenient method of communicating an investment’s desirability, and it best protects the recovery of capital- a scarce commodity in the developing countries.

Cut-off Rate

In the implementation of a sophisticated evaluation system, the use of a minimum required rate of return is necessary. The required rate of return or the opportunity cost of capital should be based on the riskiness of cash flows of the investment proposal; it is compensation to investors for bearing the risk in supplying capit81 to finance investment proposals.

Not all companies in India specify the minimum acceptable rate of return. Some of them compute the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) as the discount rate. WACC is defined either as: (i) after-tax cost of debt x weight + after-tax cost of equity x weight (cost of equity is taken as 25 per cent (a judgmental number) and weights are in proportion to the sources of capital used by a specific project); (ii) (after tax cost of borrowing × borrowings + dividend rate × equity) dividend by total capital.

Business executives in India are becoming increasingly aware of the Importance of the cost of capital, but they perhaps lack clarity among them about its computation. Arbitrary judgment of management also seems to plays role in the assessment of the cost of capital. The fallacious tendency of equating borrowing rate with minimum rate of return also persists in the case of some companies. In USA, a little mom than 50 per cent companies have been found using WACC as cut-off rate. In UK, only 14 per cent firms were found to attempt any calculation of the cost of capital. As in USA and UK, companies in India have a tendency to equate the minimum rate with interest rate or cost of specific source of finance. The phenomenon of depending on management judgement for the assessment of the cost of capital is prevalent as much in USA and UK as in India.

The assessment of risk is an important aspect of an investment evaluation. In theory, a number of techniques are suggested to handle risk. Some of them, such as the computer simulation technique are not only quite involved but are also expensive to use. How do companies handle risk in practice?

Companies in India consider the following as the four most important contributors of investment risk: selling price, product deman4 technological changes and government policies. India is fast changing from sellers’ market to buyers’ market as competition is intensifying in a large number of products; hence uncertainty of selling price and product demand are being realised as important risk factors. Uncertain government policies (in areas such as custom and excise duty and import policy), of course, , a continuous source of investment risk in developing countries like India.

Sensitivity analysis and conservative forecasts are two equally important and widely used methods of handling investment risk in India. Each of these techniques is used by a number of Indian companies with other methods while many other companies use either sensitivity analysis or conservative forecasts with other methods. Some companies also use shorter payback and inflated discount rates (risk-adjusted discount rates).

In USA risk adjusted discount rate is used by 90 per cent companies while only 10 per cent use payback and sensitivity analysis. This is also confirmed by another US study by Petty and Scott (1981). In Rockley’s survey of the British companies only one firm out of 69 used sensitivity analysis. The contrasts in risk evaluation practices in India, on the one hand, and USA and UK, on the other, are sharp and significant. Given the complex nature of risk factors in developing countries, risk evaluation cannot be handled through a single number such as NPV calculation based on conservative forecasts or risk-adjusted discount rate. Managers must know the impact on project profitability of the full range of critical variables. Hastie, an American businessman, strongly advocates the use of sensitivity analysis for risk handling and casts doubt on the survey results in USA. He states: ‘there appear to be more corporations using sensitivity analysis than surveys indicate. In some cases firms may not know that what they are undertaking is called ‘sensitivity analysis’, and it probably is not in the sophisticated, computer oriented sense. Typically, analysts or middle managers eliminate the alternative assumptions and solutions in order to simplify the decision making process for higher management”

Capital Rationing

Indian companies, by and large, do not have to reject profitable investment opportunities for lack of funds, despite the capital markets not being so well developed. This may be due to the existence of the government-owned financial system which is always ready to finance profitable projects. Indian companies do not use any mathematical technique to allocate resources under capital shortage which may sometimes arise on account of internally imposed restrictions or management’s reluctance to raise capital from outside. Priorities for allocating resources are determined by management, based on the strategic need for and profitability of projects.

Authorization

It may not be feasible in practice to specify standard administrative procedures for approving investment proposals. Screening and selection procedures may differ from one company to another. When large sums of capital expenditures are involved, the authority for the final approval may rest with top management. The approval authority may be delegated for certain types of investment projects. Delegation may be affected subject to the amount of outlay, prescribing the selection criteria and holding the authorized person accountable for results.

Funds are appropriated for capital expenditures after the final selection of investment proposals. The formal plan for the appropriation of funds is called the capital budget. Generally, the senior management tightly controls the capital expenditures. Budgetary controls may be rigidly exercised, particularly when a company is facing liquidity problem. The expected expenditure should become a part of the annual capital budget, integrated with the overall budgetary system.

Top management should ensure that funds are spent in accordance with appropriations made in the capital budget. Funds for the purpose of project implementation should be spent only after seeking formal permission from the financial manager or any other authorized person.

In India, as in UK, the power to commit a company to specific capital expenditure and to examine proposals is limited to a few top corporate officials. However, the duties of processing the examination and evaluation of a proposal are somewhat spread throughout the corporate management staff in case of a few companies.

Senior management tightly control capital spending. Budgetary control is also exercised rigidly. The expected capital expenditure proposals invariably become a part of the annual capital budget in all companies. Some companies also have formal long-range plans covering a period of 3 to 5 years. Some companies feel that long-range plans have a significant influence on the evaluation and I funding of capital expenditure proposals.

Recently, a lot of emphasis has been placed on the view that a business firm facing a complex and changing environment will benefit immensely in terms of improved quality of decision-making if capital budgeting decisions are taken in the context of its overall strategy. This approach provides the decision-maker with a central theme or a big picture to keep in mind at all times as a guideline for effectively allocating corporate financial resources. As argued by a chief financial officer: Allocating resources to investments without a sound concept of divisional and corporate strategy is a lot like throwing darts in a dark room.

In fact a close linkage between capital expenditure, at least major ones, and strategic positioning exists which has led some searchers to conclude that the set of problems companies refer to as capital budgeting is a task for general management rather than financial analyst Some recent empirical works amply support the practitioners concern for strategic considerations in capital expenditure planning and control. It is therefore B myopic point of view to ignore strategic dimensions or to assume that they are separable from the problem of efficient resource allocations addressed by capital budgeting theory.

Most companies in India consider strategy as an important factor in investment evaluation. What are the specific experiences of the companies in India in this regard? Examples of six companies showing how they defined their corporate strategy are given as follows:

• To remain market leader by highest quality and remunerative prices. This company undertook the production of a new range of product (which was marginally profitable) for competitive reasons.

• To have moderate growth for saving taxes and to set up plants for forward and backward integration.

• Our strategy is to grow, diversify and expand in related fields of technology only. Any project, which is within the strategy and satisfied profitability yardsticks, is accepted. This company found a low-profit chemical production proposal acceptable since it came within its technological capabilities.

• Strategy involves analysis of the company’s present position, nature of its relationship with the environmental forces, company’s evaluation of company’s strong and weak points.

• To take up new projects for expansion in the fields which are closer to present project/technology. This company rejected a profitable project (of deep sea fishing and ship budding) while it accepted a marginally profitable project (of paint systems) since it was very close to its current heat transfer technology.

• To stay in industrial intermediate and capital goods line, and in the process to achieve threefold profits in real terms over a 5-year period. This company rejected a highly profitable project (of manufacturing mopeds) since it was a consumer durable and accepted a marginal project.

One more example is that of an Indian subsidiary of a giant multinational that looks for projects in high technology, priority sector. This company even sold one of its profitable non-priority sector division to a sister concern to maintain is high-tech priority sector profile.

Strategic management has emerged as a systematic approach in properly positioning companies in the complex environment by balancing multiple objectives. In practice, therefore, a comprehensive capital expenditure planning and control system will not simply focus on profitability, as assumed by modern finance theory, but also on growth, competition, balance of products, total risk diversification, and managerial capability. There are umpteen examples in the developing countries Like India where unprofitable ventures are not divested even by the private sector companies because of their desirability from the point of view of consumer and employees, in particular and society, in general. Such considerations are not at all less important than profitability since the ultimate legitimating and survival of companies (and certainly that of management) hinges on them. One must appreciate the dynamics of complex forces influencing resource allocation in practice; it is not simply the use of the most refined DCF techniques.

Certain other practical considerations are as follows:

• Apart from the profitability of the project, other features like its (project’s) critical utility in the production of the main product, strategic importance of capturing the new product first, adapting to the changing market environments, have a definite bearing on investment decisions. Technological developments plays critical role in guiding investment decisions. Government policies and concessions also have a bearing on these.

• Investment in production equipment is given top priority among the existing products and the new project. Capital investment for expansion in existing lines where market potential is proved is given first priority. Capital investment in new projects is given the next priority. Capital investment for buildings, furniture, cars, office equipments etc., is done on the basis of availability of funds and immediate needs.

These statements reinforce the need for a strategic framework for problem- solving under complexities and the relevance of strategic considerations in investment planning. It also implies that resource allocation is not simply a matter of choosing most profitable new projects. What is being stressed is that the strategic framework provides a higher level screening and an integrating perspective to the whole system of capital expenditure planning and control. Once strategic questions have been answered, investment proposals may be subjected to DCF evaluation.

Capital Budgeting Techniques

In order to maximize the return to the shareholders of a company, it is important that the most profitable investment projects should be selected. It is absolutely necessary that the method adopted for appraisal of capital investment proposals is a sound one. Any appraisal method should provide for the following:

- A basis of distinguishing between acceptable and non- acceptable projects.

- Ranking of projects in order of their desirability.

- Choosing among several alternatives.

- Recognizing the fact that bigger benefits are preferable to smaller ones and early benefits are preferable to later ones.

There are several methods used for evaluating and ranking the capital investment proposals. The basic approach is to compare the investment in the project with benefits derived there-from. The important methods or techniques of capital budgeting are explained below.

Meaning

It is the traditional technique of Capital Budgeting. The term pay-back period refers to the period in which the project generates the necessary cash to recoup the initial investments. The pay-back period is generally expressed in years. The method recognizes the recovery of original investment in a project. Thus, the payback period is the number of years required to recover the cost of the investment.

The formula is:

Pay-back Period = Initial Investment (Cash outflows)

Annual Cash Inflow

The terms used in this method:

Cash outflows: It means the original cost of proposal or investment

Cash inflows: It means the profits before depreciation but after tax.

Accept or reject criterion:

While deciding between the two or more projects, usually the project having lowest pay-back period is accepted.

Advantages

- This method is easy to calculate

- It is simple to understand

- Here investment recovery period is calculated therefore business unit can know about the period within which the funds will remain tied up.

- The project having short pay-back period are accepted here. This method is more suitable to the industries where risk of obsolescence is high.

Disadvantages

- This method completely ignores all cash inflows after the pay- back period. This can be very misleading as it does not consider the total benefits occurring from the project.

- It ignores the time value of money. In this method money received now and receivable in future are considered as of equal value.

- This method does not take into consideration the entire life of the project. As a result project with large cash inflows in the latter part of payback period and less cash inflows in the earlier years may be rejected.

- This method ignores residual value.

In spite of these limitations the industries having high risk of obsolescence prefer this method. Likewise where, quick return to recover the investment is the primary goal this method is preferred.

Meaning

The capital investment proposals are judged on the basis of their relative profitability. The accounting rate of return is also known as return on investment or return on capital employed. It is normal accounting technique used to measure the increase in profit expected to result from an investment by expressing the net accounting profit arising from the investment as a percentage of that capital invested.

The formula is:

Accounting Rate of Return = Average Annual Profit after tax x 100

Average Investment

Average Investment = Initial investment + Salvage value

2

The term average annual net profit is the average of earning (after depreciation and tax) over the whole of the economic life of the project. The projects can be ranked on the basis of their accounting rate of return.

Accept or reject criterion:

The project which gives higher rate of return will be preferred for investment.

Advantages:

- It is very simple to understand and use.

- It can be readily calculated using the accounting data.

- It uses the entire stream of incomes in calculations.

Disadvantages:

- While appraising the project it uses the accounting profits not the cash inflows.

- It ignores the time value of money

- This technique does not consider the lengths of project lives.

Discounted Cash Flow Technique:

The discounted cash flow technique is an improvement on the payback period method. It takes into account the interest factor as well as the return after the pay-back period. This method involves the following stages:

- Calculation of cash flows i.e. cash inflows as well as cash outflows, over the full life of an asset.

- Discounting the cash flows by a discount factor.

- Aggregating the discount cash inflows and comparing them with the total discounted cash outflows.

Meaning of Net present value

The net present value is obtained by discounting all cash inflows and outflows attributable to a capital investment project. For this purpose, rate of discount is chosen suitably. The difference between the present value of cash inflows and present value of cash outflows is called net present value (NPV).

How to calculate the Net Present Value

Net present value method (NPV) is the most suitable method used for evaluating the capital investment projects. Net present value is calculated as below:

- Firstly the cash inflows and outflows associated with each project are worked out.

- The present value of the cash flows is calculated by discounting the cash flows at the rate of return acceptable to the management.

- The rate of return is considered as a cut-off rate. It is generally determined on the basis of cost of capital suitably adjusted to allow for the risk element involved in the project.

- The cash outflows represent the investment and commitments of cash in the project at various points of time. The working capital is taken as a cash outflow in the initial year.

- The cash inflow represents the net profit after tax but before depreciation. As depreciation is non-cash expenditure, it is added back to the net profit after tax in order to determine the cash inflows.

- The cash inflows and outflows are discounted at a certain rate and present value of cash flows is calculated.

- The difference between the present value of cash inflows and present value of cash outflows is called net present value (NPV).

Accept or reject criterion:

If the NPV is positive, the project is accepted and if it is negative, the project is rejected.

Formula:

Discounted cash flow is an evaluation of the future net cash flows generated by a project. This method considers the time value of money concept and hence it is considered better for evaluation of investment proposals. If there are mutually exclusive projects, this method is more useful. Thus, the following formula is used to determine the net present value:

Net present value (NVP) = Present value of future cash inflows – Present value of cash outflows.

Meaning

The net present value method uses discounted cash flows. It expresses cash flows in present rupees. The NPV of different projects can be compared. It implies that each project can be evaluated independent of others on its own merit. Sometimes we have to compare a number of projects each involving different amount of cash inflows and outflows. If the cash flows are different and period of the project are also different and two or more projects give positive net present value, then we have to use the technique of profitability index. It represents a ratio of the present value of future cost benefit at the required rate of return to the initial cash outflow of the investment.

Merits

- This method is helpful in comparing the project having different amounts of investment therefore it is superior to Net Present Value method.

- It considers the time value of money.

- It considers all cash inflows.

Demerits

- It is difficult to understand and to calculate.

- In case of mutually exclusive nature investment the Present Value Method is superior to this method.

Procedure

- Calculate Cash outflows and its present value.

- Calculate the present value of Cash Inflows.

- Calculate the ratio of present value of cash inflows to the present value of cash outflows. This ratio is called as profitability index.

Formula:

Profitability Index = Present value of cash inflows (PVCI)

Present value of cash outflows (PVCO)

Accept / Reject criterion:

The selection of project has based on ranking i.e. the project with the highest Profitability Index is given the first rank followed by others.

Meaning

The discounted payback period is a modified version of the payback period that considers the time value of money. Both metrics are used to calculate the amount of time that it will take for a project to “break even”, or to get the point where the net cash flows generated cover the initial cost of the project. Both the payback period and the discounted payback period can be used to evaluate the profitability and feasibility of a specific project.

Procedure to calculate Discounted Payback Period

There are two steps:

- First, we must discount (i.e., bring to the present value) the net cash flows that will occur during each year of the project.

- Second, we must subtract the discounted cash flows from the initial cost figure in order to obtain the discounted payback period. Once we’ve calculated the discounted cash flows for each period of the project, we can subtract them from the initial cost figure until we arrive at zero.

Discounted Pay - back Period = Discounted Cash outflows

Discounted Cash Inflow

When the present value of cash inflows is exactly equal to the present value of cash outflows we are getting a rate of return which is equal to our discounting rate. In this case the rate of return we are getting is the actual return on the project. This rate is called the IRR.

In the net present value calculation we assume that the discount rate (cost of capital) is known and determine the net present value of the project. In the internal rate of return calculation, we set the net present value equal to zero and determine the discount rate (internal rate of return) which satisfies this condition.

Both the discounting methods NPV and IRR relate the estimates of the annual cash outlays on the investment to the annual net of tax cash receipt generated by the investment. As a general rule, the net of tax cash flow will be composed of revenue less taxes, plus depreciation. Since discounting techniques automatically allow for the recovery of the capital outlay in computing time-adjusted rates of return, it follows that depreciation provisions implicitly form part of the cash inflow.

Internal rate of return method consists of finding that rate of discount that reduces the present value of cash flows (both inflows and outflows attributable to an investment project to zero. In other words, this true rate is that which exactly equalises the net cash proceeds over a project's life with the initial investment outlay.

If the IRR exceeds the financial standard (i.e. cost of capital), then the project is prima facie acceptable. Instead of being computed on the basis of the average or initial investment, the IRR is based on the funds in use from period to period.

The actual calculation of the rate is a hit-and-miss exercise because the rate is unknown at the outset, but tables of present values are available to aid the analyst. These tables show the present value of future sums at various rates of discount and are prepared for both single sums and recurring annual payments.

What Does IRR Mean?

There are two possible economic interpretations of internal rate of return: (i) Internal rate of return represents the rate of return on the unrecovered investment balance in the project. (ii) Internal rate of return is the rate of return earned on the initial investment made in the project.

Evaluation

A popular discounted cash flow method, the internal rate of return criteria has several virtues:

• It takes into account the time value of money.

• It considers the cash flow stream in its entirety.

• It makes sense to businessmen who want to think in terms of rate of return and find an absolute quantity, like net present value, somewhat difficult to work with.

The internal rate of return criteria, however, has its own limitations.

• It may not be uniquely defined. If the cash flow stream of a project has more than one change in sign, there is a possibility that there are multiple rates of return.

• The internal rate of return figure cannot distinguish between lending and borrowing and hence a high internal rate of return need not necessarily be a desirable feature.

The internal rate of return criterion can be misleading when choosing between mutually exclusive projects that have substantially different outlays. Consider projects P and Q

Cash Flows Period 0 & 1 | Internal rate of return (%) | Net present value (assuming k = 12%) |

P - 10,000 + 20,000 | 100 | 7,857 |

Q - 50,000 + 75,000 | 50 | 16,964 |

Both the projects are good, but Q, with its higher net present value, contributes more to the wealth of the stockholders. Yet from an internal rate of return point of view P looks better than Q. Hence, the internal rate of return criterion seems unsuitable for ranking projects of different scale.

Definition: The modified internal rate of return, or MIRR, is a financial formula used to measure the return of a project and compare it with other potential projects. It uses the traditional internal rate of return of a project and adapted to assume the difference between the reinvestment rate and the investment return.

What Does the Modified Internal Rate of Return Mean?

MIRR is a revised version of the internal rate of return (IRR), which calculates a reinvestment rate and accounts even or uneven cash flows. In fact, MIRR portrays more accurately than IRR the cost and profitability of a project because it considers the cost of capital as the reinvested rate for a firm’s positive cash flows and the financing cost as the discount rate for the firm’s negative cash flows.

If the MIRR is higher than the expected return, the investment should be undertaken. If the MIRR is lower than the expected return, the project should be rejected. Also, if two projects are mutually exclusive, the project with the higher MIRR should be undertaken.

To calculate the MIRR formula of a project, we need to know: the future value of a firm’s positive cash flows discounted at the firm’s cost of capital and the present value of a firm’s negative cash flows discounted at the cost of the firm. Let’s look at an example.

Example

Mr. Aman works for a construction company and she is asked to calculate the MIRR for two mutually exclusive projects to determine which project should be selected.

Project A has a total life of 3 years with a cost of capital 12% and a financing cost 14%. Project B has a total life of 3 years with a cost of capital 15% and a financing cost 18%.

The expected cash flows of the projects are in the table below:

Year Project A Project B

0 -1,000 -800

1 -2,000 -700

2 4,000 3,000

3 5,000 1,500

Mr. Aman calculates the future value of the positive cash flows discounted at the cost of capital.

Project A: 4,000 x ( 1 + 12% )1 + 5,000 = 9,480

Project B: 3,000 x ( 1 + 15% )1 + 1,500 = 4,950

Then, she calculates the present value of the negative cash flows discounted at the financing cost.

Project A: -1,000 + ( -2,000 ) / ( 1 + 14% )1 = -3,000

Project B: – 800 + ( -700 / 1 + 18%)1 = -1,500

To calculate the MIRR for each project Mr. Aman uses the formula:

MIRR = (Future value of positive cash flows / present value of negative cash flows) (1/n) – 1.

Therefore:

Project A: 9,480 / (3000)1/3 -1 = 5.3%

Project B: 4,950 / (1500)1/3 -1 = 10.0%

Given that these are mutually exclusive projects project B should be undertaken because it has a higher MIRR than project A.

Indian companies, by and large, do not have to reject profitable investment opportunities for lack of funds, despite the capital markets not being so well developed. This may be due to the existence of the government-owned financial system which is always ready to finance profitable projects. Indian companies do not use any mathematical technique to allocate resources under capital shortage which may sometimes arise on account of internally imposed restrictions or management’s reluctance to raise capital from outside. Priorities for allocating resources are determined by management, based on the strategic need for and profitability of projects.

In terms of financing investment projects, three essential questions must be asked:

1. How much money is needed for capital expenditure in the forthcoming planning period?

2. How much money is available for investment?

3. How are funds to be assigned when the acceptable proposals require more money than is available?

The first and third questions are resolved by reference to the discounted return on the various proposals, since it will be known which are acceptable, and in which order of preference. The second question is answered by a reference to the capital budget. The level of this budget will tend to depend on the quality of the investment proposals submitted to top management. In addition, it will also tend to depend on:

• Top management's philosophy towards capital spending (e.g., is it growth - minded or cautious)?

• The outlook for future investment opportunities that may be unavailable if extensive current commitments are undertaken;

• The funds provided by current operations; and

• The feasibility of acquiring additional capital through borrowing or equity issues.

It is not always necessary, of course, to limit the spending on projects to internally generated funds. Theoretically, projects should be undertaken to the point where the return is just equal to the cost of financing these projects. If safety and the maintaining of, say, family controls are considered to be more important than additional profits, there may be a marked unwillingness to engage in external financing and hence a limit will be placed on the amounts available for investment.

Even though the firm may wish to raise external finance for its investment programme, there are many reasons why it may be unable to do this. Examples include:

a) The firm's past record and its present capital structure may make it impossible or extremely costly to raise additional debt capital.

b) The firm's record may make it impossible to raise new equity capital because of low yields or even no yield.

c) Covenants in existing loan agreements may restrict future borrowing.

Furthermore, in the typical company, one would expect capital rationing to be largely self-imposed. Each major project should be followed up to ensure that it conforms to the conditions on which it was accepted, as well as being subject to cost control procedures.

Risk is used to describe the type of situation in which there are a number of possible states of nature, hence outcomes, but in which the decision maker can reasonably assess the probability of occurrence of each. Thus risk can be expressed in quantitative terms. Under conditions of uncertainty, in contrast, it is recognised that several out-comes are possible, but the decision-maker is unable to attach probabilities to the various states of nature. The liability is usually due to a lack of data on which to base a probability estimate. For instance, in launching a new product, the marketing manager may have an idea of what the sales in year 1 are likely to be, but he must accept that the actual level will be one of many possible levels. However, the marketing manager may be unable to specify the probability of each level being achieved, making it an uncertainty situation.

There is also, of course, the situation of complete certainty. This relates to a decision over which the decision-maker has complete control, and is thus likely to be confined to the production sphere. This is so because the existence of external agents in marketing and distribution means that knowledge is incomplete, and the creative aspect of R & D means that outcomes are unknown in advance.

If a finance manager feels he knows exactly what the outcomes of a project would be and is willing to act as if no alternative were in existence, he will be presumably acting under conditions of certainty. Thus, certainty is a state of nature, which arises when outcomes are known and determinate. In this state each action is known to lead invariably to a .specific outcome. For example, if one invests Rs. 20,000 in five yearly central government bonds which is expected to yield 7 per cent tax free return, then the return on the investment @ 7 per cent can be estimated quite precisely. This is so because we assume the Government of India to be one of the most stable forces in this country. Thus, the outcome is known to have a probability of 1. Since we know how things are or will be, the decision strategy is deterministic, we simply evaluate alternative actions and select the best one.

Risk involves situations in which the probabilities of an event occurring are known and these probabilities are objectively or subjectively determinable. The main attribute of risk situation is that the event is repetitive in nature and possesses a frequency distribution. It is the inability to predict with perfect knowledge the course of future events that introduces risk. As events become more predictable, risk is reduced. Conversely, as events become less predictable, risk is increased. Thus, if Rs. 10 lakhs is invested in stock of a company organised to extract coal from a mine, and then the probable return cannot be predicted with 100 per cent certainty. The rate of return on the above investment could vary from minus 100 per cent to some extremely high figure and because of this high variability; the project is regarded as relatively risky. Risk is then associated with project variability - the more variable the expected future returns from the project, the riskier the investment.

In contrast, when an event is not repetitive and unique in character and the finance manager is not sure about probabilities themselves, uncertainty is said to prevail. Uncertainty is a subjective phenomenon. In such situation no observation can be drawn from frequency distributions. We have no knowledge about the probabilities of the possible outcomes. It follows that if the probabilities are completely unknown or are not even meaningfully known the expected value of any decisions cannot be determined. Practically no generally accepted methods could so far be evolved to deal with situation of uncertainty while there are a number of techniques to deal with risk. In view of this, the term risk and uncertainty will be used interchangeably in the following discussion.

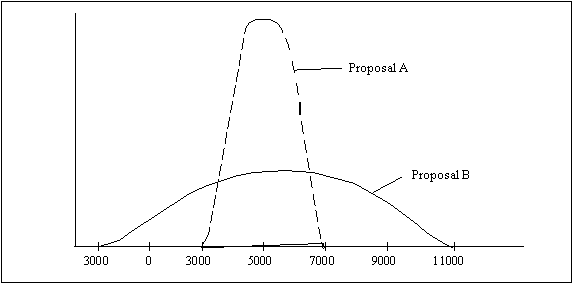

With the introduction of risk no company can remain indifferent between two investment projects with varying probability distributions as shown in Figure below. Although each investment inflows of Rs. 5,000 in its three-year life.

A look at the figure above will make it crystal clear that dispersion of the probability distribution of expected cash flows for proposal B is greater than that for proposal A. Since the task is associated with the deviation of actual outcome from that which was expected, proposal B is the riskier investment. This is why risk factor should be given due importance in investment analysis.

The first step in risk analysis is to uncover the major factors that contribute to the risk of the investment. Four main factors that contribute to the variability of results of a particular investment are cost of project, investment of cash flows, variability of cash flows and life of the project.

1. Size of the Investment

A large project involving greater investments entails more risk than the small project because in case of failure of the large project the company will have to suffer considerably greater loss and it may be forced to liquidation. Furthermore, cost of a project in many cases is known in advance. There is always the chance that the actual cost will vary from the original estimate. One can never foresee exactly what the construction, debugging, design and developmental costs will be. Rather than being satisfied with a single estimate, it seems more realistic to specify a range of costs and the probability of occurrence of each value within the range. The less confidence the decision maker has in his estimate, the wider will be the range.

2. Reinvestment of Cash Flows

Whether a company should accept a project that offers a 20 per cent return for 2 years or one that offers a 16 per cent return for 3 years would depend upon the rate of return available for reinvesting the proceeds from the 20 per cent, 2-year period. The danger that the company will not be able to reinvest funds as they become available is a continuing risk in managing fixed assets and cash flows.

3. Variability of Cash Flows

It may not be an easy job to forecast the likely returns from a project. Instead of basing investment decision on a single estimate of cash flow it would be desirable to have range of estimates.

4. Life of the Project

Life of a project can never be determined precisely. The production manager should base the investment decision on the range of life of the project.

Risk analysis is one of the most complex and slippery aspects of capital budgeting. Many different techniques have been suggested and no single technique can be deemed as best in all situations. The variety of techniques suggested to handle risk in capital budgeting fall into two broad categories: (i) Approaches that consider the stand-alone risk of a project; (ii) Approaches that consider the risk of a project in the context of the firm or in the context of the market.

This theory discusses different techniques of risk analysis, explores various approaches to project selection under risk, and describes risk analysis in practice. It is divided into nine sections as follows:

• Sensitivity analysis

• Scenario analysis

• Break-even analysis

• Simulation analysis

• Decision tree analysis

Sensitivity Analysis

Since future is uncertain, you may like to know what happens to the viability of a project when some variable like sales or investment deviates from its expected value. In other words, you would like to do sensitivity analysis. Also called “what if’ analysis it answers questions like:

What happens to net present value (or some other criterion of merit) if sales are only 60,000 units rather than the expected 75,000 units?

What happens to net present value if the life or the project turns out to be only 8 years, rather than the expected 10 years?

Procedure

Fairly simple, sensitivity analysis consists of the following steps:

1. Set up the relationship between the basic underlying factors (like the quantity sold, unit selling price, life of the project, etc.) and net present value (or some other criterion of merit).

2. Estimate the range of variation and the most likely value of each of the basic underlying factors.

3. Study the effect on net present value of variations in the basic variables. (Typically one factor is varied at time.)

Evaluation

Sensitivity analysis, a popular method for assessing risk, has certain merits:

• It forces management to identify the underlying variables and their inter-relationships.

• It shows how robust or vulnerable a project it to changes in the underlying variables.

• It indicates the need for further work. If the net present value or internal rate of return is highly sensitive to changes in some variable, it is desirable to gather further information about that variable.

Sensitivity analysis, however, suffers from severe limitations:

• It may fail to provide leads-if sensitivity analysis merely presents a complicated set of switching values it may not shed light on the risk characteristics of the project.

• The study of the impact of variation is one factor at a time, holding other factors constant may “not be very meaningful when the underlying factors are likely to be interrelated. What sense does it make to consider the effect of variation in price while holding quantity (which is likely to be closely related to price) un- changed?

Scenario Analysis

In sensitivity analysis, typically one variable is varied at a time. If variables are inter- related as they are most likely to be, it is helpful to look at some plausible scenarios, each scenario representing a consistent combination of variables.

Procedure

The steps involved in scenario analysis are as follows:

1. Select the factor around which scenarios will be built. The factor chosen must be the largest source of uncertainty for the success of the project. It may be the state of the economy or interest rate or technological development or response of the market, costs.

2. Estimate the values of each of the variables in investment analysis (investment outlay, revenues, cost, project life, and so on) for each scenario.

3. Calculate the net present value and/or internal rate of return under each scenario.

Best and Worst Case Analysis

An attempt is made to develop scenarios in which the values of variables were internally consistent. For example, high selling price and low demand typically go hand in hand. Firms often do another kind of scenario analysis called the best case and worst case analysis. In this kind of analysis the considered:

Best Scenario: High demand, high selling price, low variable cost, and so on.

Normal Scenario: Average demand, average selling price average variable cost, and so on.

Worst Scenario: Low demand, low selling price, high variable cost and so on.

The objective of such scenario analysis is to get a feel of what happens under the most favourable or the most adverse configuration of key variables, without bothering much about the internal consistency of such configurations.

Evaluation

Scenario analysis may be regarded as an improvement over sensitivity analysis because it considers variations in several variables together.

However, scenario analysis has its own limitations:

It is based on the assumption that there are few well-delineated scenarios. This may not be true in many cases. For example, the economy does not necessarily lie in three discrete states, viz., recession, stability, and boom. It can in fact be anywhere on the continuum between the extremes. When a continuum is converted into three discrete states some information is lost.

Scenario analysis expands the concept of estimating the expected values. Thus, in a case where there are 10 inputs the analyst has to estimate 30 expected values (3 × 10) to do the scenario analysis.

Break Even Analysis

In sensitivity analysis we ask what will happen to the project if sales decline or costs increase or something else happens. As a finance manager, you will also be interested in knowing how much should be produced and sold at a minimum to ensure that the project does not ‘lose money’. Such an exercise is called break- even analysis and the minimum quantity at which loss is avoided is called the break-even point. The break-even point may be defined in accounting terms or financial terms.

Accounting Break-even Analysis

Suppose you are the finance manager of OM Flour Mills. OM is considering setting up a new flour mill near Bangalore. Based on OM’s previous experience, the project staff of OM has developed the figures shown below:

| (‘000) | |

| Year 0 | Years 1-10 |

1. Investment | (20,000) |

|

2. Sales |

| 18,000 |

3. Variable costs (66+% of sales) |

| 12,000 |

4. Fixed costs |

| 1,000 |

5. Depreciation |

| 2,000 |

6. Pre-tax profit |

| 3,000 |

7. Taxes |

| 1,0000 |

8. Profit after taxes |

| 2,000 |

9. Cash flow from operation |

| 4,000 |

10. Net cash flow | (20,000) | 4,000 |

Note that the ratio of variable costs to sales is 0.667 (12/18). This means that every rupee of sales makes a contribution of Rs 0.333. Put differently, the contribution margin ratio is 0.333. Hence the break-even level of sales will be:

Fixed Costs + Depreciation = 1 + 2 = Rs. 9 million

Contribution Ratio 0.333

By way of confirmation, you can verify that the break-even level of sales is indeed Rs 9 million.

Rs. In Million | |

Sales | 9 |

Variable Costs | 6 |

Fixed Costs | 1 |

Depreciation | 2 |

Profit Before Tax | 0 |

Tax | 0 |

Profit After Tax | 0 |

A project that breaks even in accounting terms is like a stock that gives you a return of zero per cent. In both the cases you get back your original investment but you are not compensated for the time value of money or the risk that you bear. Put differently, you forego the opportunity cost of your capital. Hence a project that merely breaks even in accounting terms will have a negative NPV.

Financial Break-even Analysis

The focus of financial break-even analysis is on NPV and not accounting profit. At what level of sales will the project have a zero NPV?

To illustrate how the financial break-even level of sales is calculated, let us go back to the flour mill project. The annual cash flow of the project depends on sales as follows:

1. Variable costs : 66.67% of sales

2. Contribution : 33.33% of sales

3. Fixed costs : Rs. 1 million

4. Depreciation : Rs. 2 million

5. Pre-tax profit : (0.333 Sales) – Rs. 3 million

6. Tax (at 33.3%) : 0.333 (0.333 Sales – Rs. 3 million)

7. Profit after tax : 0.667 (0.333 Sales – Rs. 3 million)

8. Cash flow (4 + 7) : Rs. 2 million + 0.067 (0.333 Sales – Rs. 3 million)

= 0.222 Sales

Since the cash flow lasts for 10 years, its present value at a discount rate of 12 per cent is:

PV(cash flows) = 0.222 Sales x PVIFA (10 years, 12%)

= 0.222 Sales x 5.650

= 1.255 Sales

The project breaks even in NPV terms when the present value of these cash flows equals the initial investment of Rs 20 million. Hence, the financial break-even occurs when

PV (cash flows) = Investment

1.255 Sales = Rs. 20 million

Sales = Rs. 15.94 million

Thus, the sales for the flour mill must be Rs 15.94 million per year for the investment to have a zero NPV. Note that this is significantly higher than Rs 9 million which represents the accounting break-even sales.

Simulation Analysis

Sensitivity analysis indicates the sensitivity of the criterion of merit (NPV, IRR, or any other) to variations in basic factors and provides information of the following type: If the quantity produced and sold decreases by 1 per cent, other things being equal, the NPV falls by 6 per cent. Such information, though useful, may not be adequate for decision making. The decision maker would also like to know the likelihood of such occurrences. This information can be generated by simulation analysis which may be used for developing the probability profile of a criterion of merit by randomly combining values of variables which have a bearing on the chosen criterion.

Procedure

The steps involved in simulation analysis are as follows:

1. Model the project. The model of the project shows how the net present value is related to the parameters and the exogenous variables. (Parameters are input variables specified by the decision maker and held constant over all simulation runs. Exogenous variables are input variables which are stochastic in nature and outside the control of the decision maker).

2. Specify the values of parameters and the probability distributions of the exogenous variables.

3. Select a value, at random, from the probability distributions of each of the exogenous

4. Determine the net present exogenous variables and pre-specified parameter values.

5. Repeat steps (3) and (4) a number of times to get a large number of simulated net present values.

6. Plot the frequency distribution of the net present value.

Evaluation

An increasingly popular tool of risk analysis, simulation offers certain advantages:

• Its principal strength lies in its versatility. It can handle problems characterised by (i) numerous exogenous variables following any kind of distribution, and (ii) complex interrelationships among parameters, exogenous variables, and endogenous variables. Such problems often defy the capabilities of analytical methods.

• It compels the decision maker to explicitly consider the interdependencies and uncertainties characterising the project.

• Simulation, however, is a controversial tool which suffers from several shortcomings. It is difficult to model the project and specify the probability distributions of exogenous variables.

• Simulation is inherently imprecise. It provides a rough approximation of the probability distribution of net present value (or any other criterion of merit). Due to its imprecision, the simulated probability distribution may be misleading when a tail of the distribution is critical.

• A realistic simulation model, likely to be complex, would most probably be constructed by a management scientist, not the decision maker. The decision maker, lacking understanding of the model, may not use it.

• To determine the net present value in a simulation run the risk-free discount rate is used. This is done to avoid prejudging risk which is supposed to be reflected in the dispersion of the distribution of net present value. Thus the measure of net present value takes a meaning, very different from its usual one that is difficult to interpret.

Decision Tree Analysis

The scientists at Vigyanik have come up with an electric moped. The firm is ready for pilot production which is estimated to cost Rs 8 million and take one year. If the results of pilot production are encouraging the next step would be to test market the product. This will cost Rs 3 million and take two months. Based on the outcome of the test marketing, a manufacturing decision may be taken. The firm may, however, skip the test marketing phase and take a decision whether it should manufacture the product or not. If the firm decides to manufacture the product commercially it is confronted with two options: a small plant or a large plant. This decision hinges mainly on the size of the market. While the level of demand in the short run may be gauged by the results of the test market, the demand in the long run would depend on how satisfied the initial users are.

If the firm builds a large plant initially it can cater to the needs of the market when demand growth is favourable. However, if the demand turns out to be weak, the plant would operate at a low level of capacity utilisation. If the firm builds a small plant, to begin with, it need not worry about a weak market and the consequent low level capacity utilisation. However, if the market turns out to be strong it will have to build another plant soon (and thereby incur a higher total outlay) in order to save itself from competitive encroachment.

To analyse situations of this kind where sequential decision making in the face of risk is involved, decision tree analysis is a useful tool. This section discusses the technique of decision tree analysis.

Steps in Decision Tree Analysis

The key steps in decision tree analysis are:

1. Identifying the problem and alternatives

2. Delineating the decision tree

3. Specifying probabilities and monetary outcomes

4. Evaluating various decision alternatives.

Identifying the Problem and Alternatives: To understand the problem and develop alternatives; information from different sources marketing research, engineering studies, economic forecasting, financial analysis, etc has to be tapped. Imaginative effort must be made to identify the nature of alternatives that may arise as the decision situation unfolds itself and assess the kinds of uncertainties that lie ahead with respect to market size, market share, prices, cost structure, availability of raw material and power, technological changes, competitive action, and governmental regulation.

Recognising that risk and uncertainty are inherent characteristics of investment projects, persons involved in analysing the situation must be encouraged to express freely their doubts, uncertainties, and reservations and motivated to suggest contingency plans and identify promising opportunities in the emerging environment.

Delineating the Decision Tree: The decision tree, exhibiting the anatomy of the decision situation, shows:

• The decision points (also called decision forks) and the alternative options available for experimentation and action at these decision points.

• The chance points (also called chance forks) where outcomes are dependent on a chance process and the and likely outcomes at these points.

The decision tree reflects in a diagrammatic form the nature of the decision situation in terms of alternative courses of action and chance outcomes which have been identified in the first step of the analysis.

A decision tree can easily become very complex and cumbersome if an attempt is made to consider the myriad possible future events and decisions. Such a decision tree, however, is not likely to be a very useful tool of analysis. Over-elaborate, It may obfuscate the critical issues. Hence an effort should be made to keep the decision tree somewhat simple so that the decision makers can focus their attention on major “future alternatives without being drowned in a mass of trivia. One must remember the advice of Brealey and Myers.” Decision trees are like grapevines; they are productive only if vigorously pruned.

Specifying Probabilities and Monetary Values for Outcomes: Once the decision tree is delineated, the following data have to be gathered:

- Probabilities associated with each of the possible outcomes at various chance forks.

- Monetary value of each combination of decision alternative and chance outcome.

The probabilities of various outcomes may sometimes be defined objectively. For example, the probability of a good monsoon may be based on objective, historical data. More often, however, the possible outcomes encountered in real life are such that objective probabilities for them cannot be obtained. How can you, for example, define objectively the probability that a new product like an electric moped will be successful in the market? In such cases, probabilities have to be necessarily defined subjectively. This does not, however, mean that they are drawn from a hat. To be useful they have to be based on the experience, judgement, intuition, and understanding of informed and knowledgeable executives. Assessing the cash flows associated with various possible outcomes, too, is a difficult task. Again, the judgements of experts play an important role.

Evaluating the Alternatives: Once the decision tree is delineated and data about probabilities and monetary values gathered, decision alternatives may be evaluated as follows:

1. Start at the right-hand end of the tree and calculate the expected monetary value at various chance points that come first as we proceed leftward.

2. Given the expected monetary values of chance points in step 1, evaluate the alternatives at the final stage decision points in terms of their expected monetary values.

3. At each of the final stage decision points, select the alternative which has the highest expected monetary value and truncate the other alternatives. Each decision point is assigned a value equal to the expected monetary value of the alternative selected at that decision point.