UNIT 3

CAPITAL STRUCTURE THEORIES AND DIVIDEND DECISIONS

Part A- Capital Structure Theories

What Is Capital Structure?

Say you are a manager at J.D International. You want to expand, but it will require a new plant, hiring new employees, and opening new outlets. How will such expansion be financed? Through debt? Equity? How about a mixture of both?

Capital structure is the mix of owner-supplied capital (equity, reserves, surplus) and borrowed capital (bonds, loans) that a firm uses to finance business operations. Whether to finance through debt, equity, or a combination of both is a result of several factors. These include business risks, management style, control, exposure to taxes, financial flexibility, and market conditions.

In financial management, your goal is to maximize shareholders' wealth - that is, to increase the value of your firm as reflected in the stock price. The value of your company depends on its earnings as well as its weighted average cost of capital (WACC). The WACC is oftentimes referred to as your firm's cost of capital since it indicates the rate of return that equity owners and lenders can expect from the company.

In running J D International, you have the option to finance it either through debt or with equity. Hence, in computing for weighted average cost of capital, you will have to separately weigh the cost of the firm's debt and equity by its proportional weight to the total capital. Since Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) is the required return on investors' money, it's often used by management in making long-term decisions, such as mergers and company expansion.

The capital structure theories explore the relationship between your company's use of debt and equity financing and the value of the firm. We will discuss these theories one by one. The capital structure theories use the following assumptions for simplicity:

- The firm uses only two sources of funds: debt and equity.

- The effects of taxes are ignored.

- There is no change in investment decisions or in the firm's total assets.

- No income is retained.

- Business risk is unaffected by the financing mix.

- Cost of Debt (Kd) is less than the Cost of Equity(Ke) i.e. Kd<Ke

Since the publication of Modigliani and Miller's (M&M) path-breaking article in 1958, the issue of whether an optimal capital structure exists has generated considerable interest within academic circles, hence the irrelevance of capital structure rests on an absence of market imperfections. One of the most important imperfections is the presence of taxes. When taxes are very much applicable to corporate income, debt financing is advantageous. Modigliani and Miller (1963) in the work “Corporate Income Taxes and the Cost of Capital: A Correction” have made a correction to bring out the tax advantages of debt financing. In this work they viewed the value of the firm as a function of leverage and the tax rate. While dividends and retained earnings are not deductible for tax purposes, interest on debt is a tax-deductible expense. As a result, the total income available for both the shareholders and debt holders is greater when debt capital is used. The tax deductibility of corporate interest payments favours the use of debt. This simple effect however, can be complicated by the existence of personal taxes (Miller 1977) and non-debt tax shields (DeAngelo and Masulis 1980). Castanias(1983) cross-sectional test of capital structure irrelevance hypothesis and the tax shelter-bankruptcy cost hypotheses showed results inconsistent with the capital structure irrelevance hypothesis but consistent with the tax shelter-bankruptcy cost hypotheses. Stulz (1990) argued that debt can have both a positive as well as negative effect on the value of the firm (even in the absence of corporate taxes and bankruptcy cost). Stulz (1990) assumed that managers have no equity ownership in the firm and receive utility by managing a larger firm. The “power of manager” may motivate the self-interested managers to undertake negative present value project. To solve this problem, shareholders force firms to issue debt however, if firms are forced to pay out funds, they may have to forgo positive present value projects. Therefore, the optimal debt structure is determined by balancing the optimal agency cost of debt and the agency cost of managerial discretion.

But there are few controversial findings. Schnabel (1984) showed that an optimal capital structure does not involve exclusive reliance on debt financing in contrast to the classic result of Modigliani and Miller. Berens and Cuny (1995) have revisited the capital structure puzzle in the perspective of growth. Nominal firm growth, due to inflation or real growth, distorts the debt ratio as a measure of tax shielding. Firms typically issue debt characterized by fixed interest payments, even when they expect positive growth in earnings. To totally shield itself from corporate tax, a firm should not set debt equal to firm value. Instead, it should set its current interest payments equal to current earnings.

Capital Structure Theories

According to NI approach a firm may increase the total value of the firm by lowering its cost of capital. When cost of capital is lowest and the value of the firm is greatest, we call it the optimum capital structure for the firms and at this point, the market price per share is maximised.

The same is possible continuously by lowering its cost of capital by the use of debt capital. In other words, using more debt capital with a corresponding reduction in cost of capital, the value of the firm will increase.

The same is possible only when:

- Cost of Debt (Kd) is less then Cost of Equity (Ke);

- There are no taxes, and

- The use of debt does not change the risk perception of the investors since the degree of leverage is increased to that extent.

Since the amount of debt in the capital structure increases, weighted average cost of capital decreases which leads to increase the total value of the firm. So, the increased amount of debt with constant amount of cost of equity and cost of debt will highlight the earnings of the shareholders.

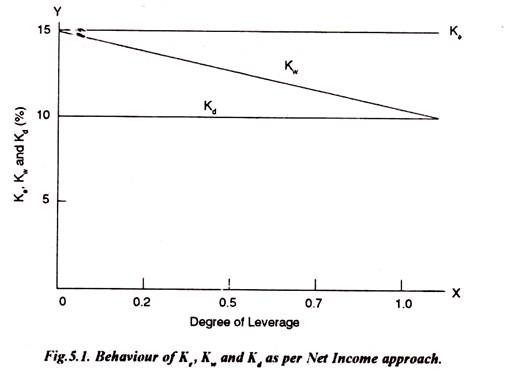

It is interesting to note that the NI approach can also be graphically presented as under:

The degree of leverage is plotted along with the X-axis whereas Ke, Kw and Kd on the Y- axis. It reveals that when the cheaper debt capital in the capital structure is proportionally increased, the weighted average cost of capital Kw, decreases and consequently the cost of debt Kd. Thus, it is needless to say that the optimal capital structure is the minimum cost of capital, if financial leverage is one, in other words, the maximum application of debt capital.

The value of the firm (V) will also be the maximum at this point.

Now we want to highlight the Net Operating Income (NOI) Approach which was advocated by David Durand based on certain assumptions.

They are:

- The overall capitalization rate of the firm Kw is constant for all degree of leverage;

2. Net operating income is capitalized at an overall capitalisation rate in order to have the total market value of the firm.

Thus, the value of the firm, V, is ascertained at overall cost of capital (Kw):

V = EBIT/ Kw (Since both are constant and independent of leverage)

3. The market value of the debt is then subtracted from the total market value in order to get the market value of equity.

S = V-T

4. As the Cost of Debt is constant, the cost of equity will be:

Ke = EBIT – I / S

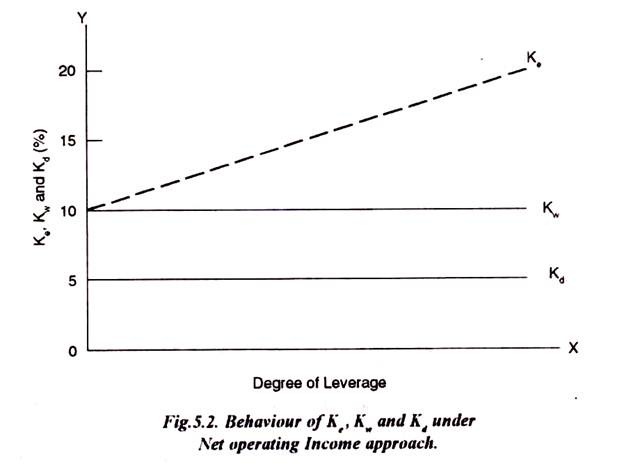

The NOI Approach can be illustrated with the help of the following diagram:

Under this approach, the most significant assumption is that the Ku is constant irrespective of the degree of leverage. The segregation of debt and equity is not important here and the market capitalizes the value of the firm as a whole. Thus, an increase in the use of apparently cheaper debt funds is offset exactly by the corresponding increase in the equity-capitalisation rate.

So, the weighted average Cost of Capital Kw and Kd remain unchanged for all degrees of leverage. Needless to mention here that as the firm increases its degree of leverage, it becomes more risky proposition and investors are to make some sacrifice by having a low P/E ratio.

It is accepted by all that the judicious use of debt will increase the value of the firm and reduce the cost of capital. So, the optimum capital structure is the point at which the value of the firm is highest and the cost of capital is at its lowest point. Practically, this approach encompasses all the ground between the net income approach and the net operating income approach i.e., it may be said as intermediate approach.

The traditional approach explains that up to a certain point, debt-equity mix will cause the market value of the firm to rise and the cost of capital to decline. But after attaining the optimum level, any additional debt will cause to decrease the market value and to increase the cost of capital.

In other words, after attaining the optimum level, any additional debt taken, will offset the use of cheaper debt capital since the average cost of capital will increase along with a corresponding increase in the average cost of debt capital.

Thus, the basic, proposition of this approach are enumerated below:

- The cost of debt capital, Kd, remains constant more or less up to a certain level and thereafter rises.

- The cost of equity capital, Ke, remains constant more or less or rises gradually up to a certain level and thereafter increases rapidly.

- The average cost of capital, Kw, decreases up to a certain level, remains unchanged more or less and thereafter rises after attaining a certain level.

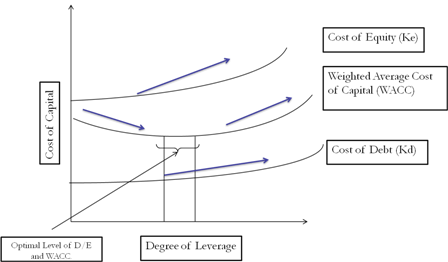

The traditional approach can graphically be represented as under taking the data from the previous illustration.

It is found from the above, the average cost curve is U-shaped. That is, at this stage the cost of capital would be minimum. If we draw a perpendicular to the X-axis, the same will indicate the optimum capital structure for the firm.

Thus, the traditional position implies that the cost of capital is not independent of the capital structure of the firm and that there is an optimal capital structure. At that optimal structure, the marginal real cost of debt (explicit and implicit) is the same as the marginal Real cost of equity in equilibrium.

For degree of leverage before that point, the marginal real cost of debt is less than of equity, beyond that point the marginal real cost of debt excess that of equity.

Variations on the Traditional Theory:

We know that this theory underlies between the Net Income Approach and the Net Operating Income Approach. Thus, there are some distinct variations in this theory. Some followers of the traditional school of thought suggest that Ke does not practically rise till some critical conditions arise.

After attaining that level only, the investors apprehend the increasing financial risk and penalize the market price of the shares. This variation expresses that a firm can have lower cost of capital with the initial use of leverage significantly.

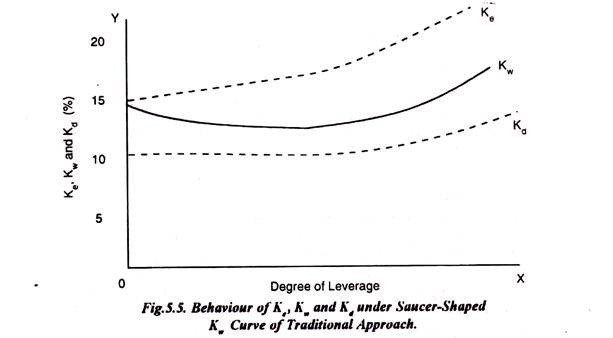

This variation in Traditional Approach is depicted as under:

Other followers e.g., Solomon, are of opinion that K is as being saucer shaped along with a horizontal middle range. It explains that optimum capital structure has a range where the cost of capital is rather minimised and where the total value of the firm is maximised.

Under the circumstances, a change in leverage has, practically, no effect on the total firm’s value. So, this approach grants some sorts of variation in the optimal capital structure for various firms under debt-equity mix.

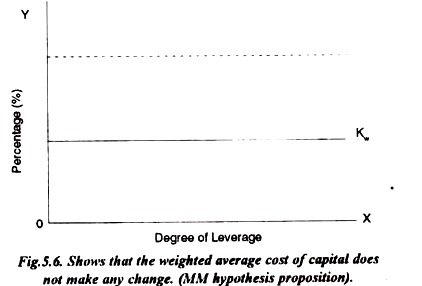

Modigliani-Miller (MM) advocated that the relationship between the cost of capital, capital structure and the valuation of the firm, should be explained by NOI (Net Income Operating Approach) by making an attack on the Traditional Approach.

The Net Income Operating Approach, we know, supply proper justification for the irrelevance of the capital structure. In this context, MM support the NOI approach on the principle that the cost of capital is not dependent on the degree of leverage irrespective of the debt-equity mix.

In other words, according to their thesis, the total market value of the firm and the cost of capital are independent of the capital structure. They advocated that the weighted average cost of capital does not make any change with a proportionate change in debt-equity mix in the total capital structure of the firm.

The same can be shown with the help of the following diagram:

Trade Off Theory

The term trade-off theory is used by different authors to describe a family of related theories. Management running a firm evaluates the various costs and benefits of alternative leverage plans and strives to bring a trade-off between them. Often it is assumed that an interior solution is obtained so that marginal costs and marginal benefits are balanced. Thus, trade-off theory implies that company’s capital structure decision involves a trade-off between the tax benefits of debt financing and the costs of financial distress. When firms adjust their capital structure, they tend to move toward a target debt ratio that is consistent with theories based on tradeoffs between the costs and benefits of debt. Hovakimian, Opler, and Titman (2001) empirical work, explicitly account for the fact that firms may face impediments to movements toward their target ratio, and that the target ratio may change over time as the firm's profitability (P) and stock price change.

Static Trade-off Theory

In a static trade-off framework the firm is viewed as setting a target debt to value ratio and gradually moving towards it (Myers 1984). The theory says that every firm has an optimal debt–equity ratio that maximizes its value. The theory affirms that firms have optimal capital structure, which they determine by trading off the costs against the benefits of the use of debt and equity. The benefits from debt tax shield are thus adjusted against cost of financial distress. Agency cost, informational asymmetry and transaction cost are some of the other costs to be mitigated. The theory predicts that an optimal target financial debt ratio exists, which maximizes the value of the firm. The optimal point can be attained when the marginal value of the benefits associated with debt issues exactly offsets the increase in the present value of the costs associated with issuing more debt (Myers 2001).

Dynamic Trade-off Theory

Implementing the role of time is very significant in identifying the optimal capital structure. In a dynamic model, the correct financing decision typically depends on the financing margin that the firm anticipates in the next period. Some firms expect to pay out funds in the next period, while others expect to raise funds. Stiglitz (1972) took the drastic step of assuming away uncertainty. The first dynamic models to consider the tax savings versus bankruptcy cost trade-off are Kane, Marcus, and MacDonald (1984) and Brennan and Schwartz (1984). Their models took into consideration: uncertainty, taxes, and bankruptcy costs, but no transaction costs. These firms maintain high levels of debt to take advantage of the tax savings and to adjust to shocks without any cost as there is no transaction cost. Strebulaev (2007) analyzed a model quite similar to that of Fischer, Heinkel, and Zechner (1989) and Goldstein, Ju, and Leland (2001). Again, if firms optimally finance only periodically because of transaction costs, then the debt ratios of most firms will deviate from the optimum most of the time. In the model, the firm's leverage responds less to short-run equity fluctuations and more to long-run value changes.

Signaling Theory

The pioneering study of Donaldson (1961) examined how companies actually establish their capital structure.

- Firms prefer to rely on internal accruals, that is, on retained earnings and depreciation cash flow.

- Expected future investment opportunities and expected future cash flows influence target dividend payout ratios. Firms set the target payout ratios at such a level that capital expenditures, under normal circumstances are covered by internal accruals.

- Dividends tend to be sticky in the short run. Dividends are raised only when the firm is confident that the higher dividend can be maintained; dividends are not lowered unless things are very bad.

- If a firm’s internal accruals exceed its capital expenditure requirements, it will invest in marketable securities, retire debt, raise dividend, and resort to acquisitions or buyback its shares.

- If a firm’s internal accruals are less than its non-postponable capital expenditures, it will first draw down its marketable securities portfolio and then seek external finance. When it resorts to external finance, it will first issue debt, then convertible debt, and finally equity stock, thus, there is a pecking order of financing.

Noting the inconsistency between trade-off theory and the observed pecking order of financing, Myers and Majluf (1984) proposed a new theory, called the signalling, or asymmetric information theory of capital structure. They demonstrated that with asymmetric information, equity issues are rationally interpreted on average as bad news, since managers are motivated to make issues when the stock is overpriced. Ross’s (1977) model suggests that the value of firms will rise with leverage, since increasing leverage increases the market’s perception of value. Asquith and Mullins (1983), Masulis and Korwar (1986), and Mikkelson and Partch (1986) also empirically observed that announcements of new equity issues are greeted by sharp declines in stock prices. This is a major reason why equity issues are comparatively rare among large established corporations. Debt also plays an important role in allowing investors to generate information useful for monitoring management and implementing efficient operating decisions Harris and Raviv (1990).

Part B- Dividend Decisions

Once a company has been formed and continues in operation, it should have earnings to retain or to distribute to the owners. This disposition of these earnings is a fundamental problem of financial management. In organisations, which are closely held, the problem is not there because the shareholders run the organisation themselves and can dictate the terms. In large organisations, however, the situation is different. Here the policy concerning the distribution of earnings is normally delegated to the directors of the company by the shareholders. However, they retain the final approval authority and the dividend is paid only after final approval of the shareholders in the Annual General Meeting. Once it is approved in the AGM, the dividend cheque is sent to the shareholders within a month and is normally payable in the city of residence of the shareholder so as to expedite the payment to him.

The management of an enterprise has an important financial decision to decide about the disposition of income left after meeting all business expenses. Generally, of the total business profits, a portion is retained for reinvestment in the business and rest is distributed to shareholders as dividend.

Organisations finance a large portion of their needs internally, that is, from retained earnings and from non-cash charges, such as depreciation, to the extent that they are covered by earnings. To the extent that the organisations are dependent on internal funds to meet their capital and other requirements, there could be a concern that the funds retained may not be used as productively as they might be elsewhere. In a small concern (especially proprietorship/ partnership) the owners are very likely to compare the return to be gained from retained earnings in the business and the return that they might make from some other investment of equivalent risk. Because they do not participate directly in formulating dividend policy, shareholders in large companies do not have the chance to make this direct comparison. Thus earnings that are retained in many companies have not met a "market test" and therefore we may not be sure that they should have been retained.

The objective of the dividend policies should be to divert funds from the less productive operations to more productive ones. But it is very difficult for the directors and the management to accept the fate of a declining company and to allow the gradual liquidation of their company, as would be suggested by economic thought. If the management finds itself in a declining industry, they want to retain more funds for the business operations and pay out less so as to conserve the funds. Something that is not beneficial for the shareholders. They also try to retain more to fund other more profitable investments so the continuity of the corporation can be maintained.

The important issue is to decide the portion of profit to declare for dividend payout and for retaining in business. The dividend policy decision involves two questions:

• What fraction of earnings should be paid out, on average, over time? and

• Should the firm maintain a steady, stable dividend growth rate?

Before we try and answer these questions, let us look at the theories related to dividend decisions. After that we will look at the empirical evidence of the same.

Legal Aspects

The amount of dividend that can be legally distributed is governed by company law, judicial pronouncements in leading cases, and contractual restrictions. The important provisions of company law pertaining to dividends are described below.

- Companies can pay only cash dividends (with the exception of bonus shares). Apart from cash, dividend may also be remitted by cheque or by warrant. The same may also be transmitted electronically to shareholders after obtaining their consent in this regard to the bank account number specified by them. The step has been proposed by the Department of Company Affairs to avoid delay in the remittance of dividend.

2. Dividends can be paid only out of the profits earned during the financial year after providing for depreciation and after transferring to reserves such percentage of profits as prescribed by law. The Companies (Transfer to Reserve) Rules, 1975, provide that before dividend declaration, a percentage of profit as specified below should be transferred to the reserves of the company.

- Where the dividend proposed is up to 10 per cent of the paid up capital, no amount of the current profits need to be transferred.

- Where the dividend proposed exceeds 10 per cent but not 12.5 per cent of the paid-up capital, the amount to be transferred to the reserves should not be less than 2.5 per cent of the current profits.

- Where the dividend proposed exceeds 12.5 per cent but not 15 per cent, the amount to be transferred to reserves should not be less than 5 per cent of the current profits.

- Where the dividend proposed exceeds 15 per cent but not 20 per cent, the amount to be transferred to reserves should not be less than 7.5 per cent of the current profits.

- Where the dividend proposed exceeds 20 per cent, the amount to be transferred to reserve should not be less 10 per cent.

- A company may voluntarily transfer a percentage higher than 10 per cent of the current profits to reserves in any financial year provided the following conditions are satisfied:

- It ensures that the dividend declared in that financial year is sufficient to maintain average rate of dividend declared by it over three years immediately preceding the financial year.

- In case, it has issued bonus shares in the year in which dividend is declared or in the three years immediately preceding the financial year, it maintains the amount of dividend equal to the average amount of dividend declared over the three years immediately preceding the financial year.

However, maintenance of such minimum rate or quantum of dividend is not necessary if the net profits after tax in a financial years are lower by 20 per cent or more than the average profits after tax of the two immediately preceding financial years.

g. A newly incorporated company is prohibited from transferring more than then percent of its profits to reserves. The 'current profit' for the purpose of transfer to reserves will be profits after providing for statutory transfer to the Development Rebate Reserve and arrears of depreciation if any.

3. Due to inadequacy or absence of profits in any year, dividend may be paid out of the accumulated profits of previous years. In this context, the following conditions, as stipulated by the companies (Declaration of Dividend out of Reserves) Rules, 1975, have to be satisfied.

- The rate of the declared dividend should not exceed the average of the rates at which dividend was declare by the company in 5 years immediately preceding that year or 10 per cent of its paid-up capital, whichever is less.

- The total amount to be drawn from the accumulated profits earned in previous years and transferred to the reserves should not exceed an amount equal to one-tenth of the sum of its paid-up capital and free reserves and the amount so drawn should first be utilized to set off the losses incurred in the financial year before any dividend in respect of preference or equity shares is declared.

- The balance of reserves after such drawal should not fall below 10 per cent of its paid-up capital.

4. Dividends cannot be declared for past years for which accounts have been adopted by the shareholders in the annual general meeting.

5. Dividend declared, interim or final, should be deposited in separate bank account within 5 days from the date of declaration and dividend will be paid within 30 days from such a date.

6. Dividend including interim dividend once declared becomes a debt. While the payment of interim dividend cannot be revoked, the payment of final dividend can be revoked with the consent of the shareholders.

Procedural Aspects

The important events and dates in the dividend payment procedure are:

- Board Resolution: The dividend decision is the prerogative of the board of directors. Hence, the board of directors should in a formal meeting resolve to pay the dividend.

2. Shareholder Approval: The resolution of the board of directors to pay the dividend has to be approved by the shareholders in the annual general meeting. However, their approval is not required in the case of declaration of interim dividend. Further, it should be noted that the shareholders in the annual general meeting have neither the power to declare the dividends (if the Board of Directors do not recommend it) nor to increase the amount or dividend. However, they can reduce the amount of the proposed dividend.

3. Record Date: The dividend is payable to shareholders whose names appear in the register of members as on the record date.

4. Dividend Payment: Once a dividend declaration has been made, dividend warrant must be posted within 30 days. Within a period of 7 days, after the expiry of 30 days, unpaid dividends must be transferred to a special account opened with a scheduled bank.

In case the company fails to transfer the unpaid dividend to the 'unpaid dividend account' within 37 days of the declaration of dividend, an interest of 12 per cent per annum on the unpaid amount is to be paid by the company. The interest so accruing is to be paid to the shareholders in the proportion of the dividend amount remaining unpaid to them.

The dividend will be paid to the registered shareholder or to his order or to his banker in case a share warrant has been issued to the bearer of such a share warrant. In the case of joint-holders, the dividends should be paid to the first joint- holder.

Further, as per the notification issued by the Department of Company Affairs, the payment of dividend to the shareholders involving the fraction of 50 paise and above be rounded off to the rupee and the fraction of less than 50 paise may be ignored.

In the case of dematerialized shares (i.e., the shares held in electronic form), the corporate firms are required to collect the list of members holdings shares in the depository and pay them the dividend.

5. Unpaid dividend: If the money transferred to the 'unpaid dividend account' in the scheduled bank remains unpaid / unclaimed for a period of 7 years from the date of such transfer, the company is required to transfer the same to the 'Investor, Education and Protection Fund' established for the purpose.

Dividend Decision Models

Walter's model is one of the earliest dividend models is adapted from the Gordon's model for valuation of an equity share.

Gordon's model gives us the cost of internally generated common equity, ke

Ke = dividend in Year 1 + (annual growth rate in dividend)

Market price

Which can also be written as:

Ke = D1 + g

P0

Hence the dividend growth rate can be subtracted from the cost of equity capital to get the present value of the share price which should be the market price according to the formula.

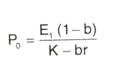

Walter adjusted the above formula to reflect the earnings retention and rewrote the equation as:

P0 = D1

Ke - rb

Here, b is the percentage of earnings retained, and r is the expected rate of profitability from the retained earnings.

It follows from the formula that if the earnings retained gives you a higher return than the cost of capital, you would get a positive return and the share price would go up and otherwise the share price would come down because of the higher earnings retained.

Walter's formula highlights the return on retained earnings relative to the average market rate of return on investment (market capitalisation rate) as the critical determinant of dividend policy. A high rate of return on retained earnings indicates a low payout ratio, whereas a low rate relative to the market average indicates the desirability of a high payout ratio to increase the price of the equity shares.

Therefore to increase the share valuation a company may go in for a higher payout in the form of a dividend. But this reduces the growth rate of the dividends (keeping all other things constant) bringing it back to square one.

Also a high dividend policy may force the firm to go to the capital markets more often. In practice, most firms try to follow a policy of paying a steadily increasing dividend. This policy provides investors with stable, dependable income, and if the signaling theory is correct, it also gives investors information about management's expectations for earnings growth.

Most firms use the residual dividend model to set a long run target payout ratio which permits the firm to satisfy its equity requirements with retained earnings.

One very popular model explicitly relating the market value of the firm to dividend policy is developed by Myron Gordon.

Assumptions:

Gordon’s model is based on the following assumptions.

- The firm is an all Equity firm

- No external financing is available

- The internal rate of return (r) of the firm is constant.

- The appropriate discount rate (K) of the firm remains constant.

- The firm and its stream of earnings are perpetual

- The corporate taxes do not exist.

- The retention ratio (b), once decided upon, is constant. Thus, the growth rate (g) = br is constant forever.

- K > br = g if this condition is not fulfilled, we cannot get a meaningful value for the share.

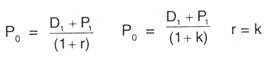

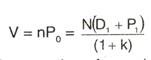

According to Gordon’s dividend capitalisation model, the market value of a share (Pq) is equal to the present value of an infinite stream of dividends to be received by the share.

Thus:

The above equation explicitly shows the relationship of current earnings (E,), dividend policy, (b), internal profitability (r) and the all-equity firm’s cost of capital (k), in the determination of the value of the share (P0).

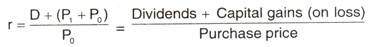

According to Modigliani and Miller (M-M), dividend policy of a firm is irrelevant as it does not affect the wealth of the shareholders. They argue that the value of the firm depends on the firm’s earnings which result from its investment policy.

Thus, when investment decision of the firm is given, dividend decision the split of earnings between dividends and retained earnings is of no significance in determining the value of the firm. M – M’s hypothesis of irrelevance is based on the following assumptions.

9. The firm operates in perfect capital market

10. Taxes do not exist

11. The firm has a fixed investment policy

12. Risk of uncertainty does not exist. That is, investors are able to forecast future prices and dividends with certainty and one discount rate is appropriate for all securities and all time periods. Thus, r = K = Kt for all t.

Under M – M assumptions, r will be equal to the discount rate and identical for all shares. As a result, the price of each share must adjust so that the rate of return, which is composed of the rate of dividends and capital gains, on every share will be equal to the discount rate and be identical for all shares.

Thus, the rate of return for a share held for one year may be calculated as follows:

Where P^ is the market or purchase price per share at time 0, P, is the market price per share at time 1 and D is dividend per share at time 1. As hypothesised by M – M, r should be equal for all shares. If it is not so, the low-return yielding shares will be sold by investors who will purchase the high-return yielding shares.

This process will tend to reduce the price of the low-return shares and to increase the prices of the high-return shares. This switching will continue until the differentials in rates of return are eliminated. This discount rate will also be equal for all firms under the M-M assumption since there are no risk differences.

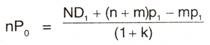

From the above M-M fundamental principle we can derive their valuation model as follows:

Multiplying both sides of equation by the number of shares outstanding (n), we obtain the value of the firm if no new financing exists.

If the firm sells m number of new shares at time 1 at a price of P^, the value of the firm at time 0 will be

The above equation of M – M valuation allows for the issuance of new shares, unlike Walter’s and Gordon’s models. Consequently, a firm can pay dividends and raise funds to undertake the optimum investment policy. Thus, dividend and investment policies are not confounded in M – M model, like waiter’s and Gordon’s models.

Criticism:

Because of the unrealistic nature of the assumption, M-M’s hypothesis lacks practical relevance in the real world situation. Thus, it is being criticised on the following grounds.

- The assumption that taxes do not exist is far from reality.

- M-M argue that the internal and external financing are equivalent. This cannot be true if the costs of floating new issues exist.

- According to M-M’s hypothesis the wealth of a shareholder will be same whether the firm pays dividends or not. But, because of the transactions costs and inconvenience associated with the sale of shares to realise capital gains, shareholders prefer dividends to capital gains.

- Even under the condition of certainty it is not correct to assume that the discount rate (k) should be same whether firm uses the external or internal financing.

If investors have desire to diversify their port folios, the discount rate for external and internal financing will be different.

5. M-M argues that, even if the assumption of perfect certainty is dropped and uncertainty is considered, dividend policy continues to be irrelevant. But according to number of writers, dividends are relevant under conditions of uncertainty.

According to Graham & Dodd, “Stock Market places more weight on dividends than on retained earnings”. So it is believed that if the dividend is paid then the stock prices will behave more accurately as the company wants to behave their share prices, but non-payment will liberally disappoint the share prices of the company. As per this model, valuation of share price is measured with the weight attached to the dividend. So the weight of the dividend will be equal to four times the weight attached to the retained earnings.

As derived the formula will be:

P = m{D + (D+R)/3}

= m(4D/3) + m(R/3)

This approach is an oral and subjective approach as it could not be possible to determine the weights as asked in the given policy.