UNIT 4

Money, prices and inflation

Money supply refers to the amount of money which is in circulation in an economy at any given time. It is the total stock of money held by the people consisting of individuals, firms, State and its constituent bodies except the State treasury, Central Bank and Commercial Banks.

Professor Friedman defines the money supply at any moment of time as “literally the number of dollars people are carrying around in their pockets, the number of dollars they have to their credit at banks or dollars they have to their credit at banks in the form of demand deposits, and also commercial bank time deposits.”

Money supply is an important factor for the economic development and priced stability in the economy. Money supply denoted as M1, means demand deposit with commercial bank plus currency with the public.

Money supply has wider definition characterized as M2 and M3, M2 definition includes M1 plus time deposits of commercial banks in the supply of money. M3 includes M2 plus deposits of savings banks, building societies, loan associations, and deposits of other credit and financial institutions.

Determinants of money supply

- Size of the Monetary Base: Money supply depends upon the size of the monetary base. The monetary base refers to the group of assets which empowers the monetary authorities to issue currency money. Money supply changes with changes in the monetary base. The monetary base of an economy consists of monetary gold stock, reserve assets such as government securities, bonds and bullion, foreign exchange reserve with the central bank and the amount of central bank’s credit outstanding. In the present times, gold stock is not considered as part of the monetary base.

- Community’s Choice: The relative amount of cash and demand deposits held by the people also influences the supply of money. If the people prefer to make check payments much more than cash payments, the total money supply maintained by a given monetary base would be larger and vice versa. Since money deposited in commercial banks generates derivative deposits and expand the supply of bank money through the credit multiplier, people’s preference of bank money to cash would increase the supply of money. However, the choice of the community is determined by factors such as banking habits, per capita income, availability of banking facilities and the level of economic development. If these factors are developed, the money supply would be larger and vice versa.

- Extent of Monetization: Monetization refers to the use of money as a medium of exchange. The choice of the community for money as a liquid asset depends upon the extent of monetization of the economy. If monetization is high, demand for money would be high and vice versa.

- Cash Reserve Ratio: The Cash Reserve Ratio refers to the ratio of a bank’s cash holdings to its total deposit liabilities. It determines the coefficient of the credit multiplier. The CRR is determined by the Central Bank of a country. The credit multiplier (m) is determined as the reciprocal of the CRR (r). Therefore m = 1/r. Excess funds with the commercial banks multiplied by the credit multiplier will give us the extent of credit creation by the commercial banks. Lower the CRR, greater will be value of the credit multiplier and therefore greater will be the supply of bank money and vice versa.

- Monetary Policy of the Central Bank: Monetary policy is defined as the policy of the Central Bank with regard to the cost and availability of credit in the economy. The monetary policy of the Central Bank of any country will be according to the macroeconomic conditions. Thus under inflationary conditions, the Central Bank may follow restrictive monetary policy and thereby reduce the supply of bank money by pursuing both qualitative and quantitative measures of controlling money supply. Similarly under recessionary conditions the Central Bank may follow expansionary monetary policy and thereby raise the supply of money in the economy.

- Fiscal Policy of the Government: Fiscal Policy is defined as a policy concerning the income and expenditure of the government. While the government raises revenue through various sources like different types of taxes, borrowing and through deficit financing, it spends the money raised for various developmental and non-developmental purposes. When the government raises revenue by imposing fresh taxes or by raising the existing level of taxes, it helps to reduce money supply. Similarly, market borrowing by the government reduces money supply and raises the market interest rates. This is known as the crowding out effect of government borrowing. When the government spends the money so raised, money supply increases. However, when the government runs a deficit budget, it adds to the existing stock of money supply and thus raises the supply of money in the economy. The opposite will be the impact of a surplus budget but surplus budgets are a rarity in modern times.

- Velocity of Circulation of Money: Velocity of circulation of money refers to the average number of times a unit of money as a medium of exchange changes hands during a given year. Money supply is measured as total money in circulation V). Thus higher themultiplied by the velocity of circulation (M velocity of circulation of money, higher will be the money supply and vice versa.

Velocity of circulation of money

The velocity of circulation of money determines the flow of money supply in an economy in a given period of time, normally such a period is one year. The average number of times a unit of money changes hands is known as the velocity of circulation of money. The supply of money in a given period is obtained by multiplying the money in circulation with the coefficient of velocity of V where M refers to the total amount of moneycirculation i.e., M in circulation and V refer to the velocity of circulation of money in the given period.

Factors influencing Velocity of Circulation of Money

- Money supply - Velocity of money depends upon the supply of money in the economy. The velocity of money will increase, if the supply of money in the economy is less than its requirements and vice versa.

- Value of money – During inflation when the value of money decreases the velocity of money is high because people will like to part with money as soon as possible. During deflation the value of money rises, the velocity of money is low as the people will like to keep money with them.

- Credit facilities – With the expansion of lending and borrowing facilities in the country, the velocity of money increases. Thus the growth of credit institutions has a good affect on the velocity of money.

- Volume of trade – The velocity of money increases as the volume of trade increases the number of transaction and the velocity of money decreases as the volume of trade increases.

- Frequency of transaction – The number of payments and receipts increases with the increase in the frequency of transaction and leads to increase in velocity of money. Similarly, the velocity of money decreases with the decrease in frequency of transaction.

- Business conditions – During the period of hectic business conditions the velocity of money increases and during slump condition it decreses.

- Business integration – The velocity of money increases if the business is vertically disintegrated. If the business is vertically integrated, the velocity of money will be less.

- Payment system – The frequency with which the labour force is paid and the speed with which the bills for goods are settled determines the velocity of money.

- Regularity of income – The velocity of money increases if the people receives income at regular intervals as they will spend their income freely.

- Propensity to consume – Other things remaining the same, greater the tendency of the people to consume, higher will be the velocity of money. Lower the propensity of money, lesser will be the velocity of money.

Key takeaways –

- The velocity of money is important for measuring the rate at which money in circulation is being used for purchasing goods and services.

- Determinants of Money Supply includes The Required Reserve Ratio, The Level of Bank Reserves, Public’s Desire to Hold Currency and Deposits, High Powered Money and the Money Multiplier

The Classical Approach:

The classical economists didn't explicitly formulate demand for money theory but their views are inherent within the quantity theory of money. They emphasized the transactions demand for money in terms of the rate of circulation of cash .this is often because money acts as a medium of exchange and facilitates the exchange of products and services. In Fisher’s “Equation of Exchange”.

MV=PT

Where M is that the total quantity of cash, V is its velocity of circulation, P is that the price level, and T is that the total amount of goods and services exchanged for money.

The right hand side of this equation PT represents the demand for money which, in fact, “depends upon the worth of the transactions to be undertaken within the economy, and is adequate to a constant fraction of these transactions.” MV represents the supply of money which is given and in equilibrium equals the demand for money. Thus the equation becomes

Md = PT

This transactions demand for money, in turn, is decided by the extent of full employment income. This is often because the classicists believed in Say’s Law whereby supply created its own demand, assuming the full employment level of income. Thus the demand for money in Fisher’s approach may be a constant proportion of the extent of transactions, which successively, bears a continuing relationship to the extent of value. Further, the demand for money is linked to the volume of trade happening in an economy at any time.

Thus its underlying assumption is that individuals hold money to buy goods.

But people also hold money for other reasons, like to earn interest and to supply against unforeseen events. It’s therefore, impracticable to say that V will remain constant when M is modified. The foremost important thing about money in Fisher’s theory is that it's transferable. But it doesn't explain fully why people hold money. It doesn't clarify whether to incorporate as money such items as time deposits or savings deposits that aren't immediately available to pay debts without first being converted into currency.

It was the Cambridge cash balance approach which raised an extra question: Why do people actually want to carry their assets within the form of money? With larger incomes, people want to form larger volumes of transactions which larger cash balances will, therefore, be demanded.

The Cambridge demand equation for money is

Md=kPY

Where Md is that the demand for money which must equal the supply to money (Md=Ms) in equilibrium within the economy, k is that the fraction of the important money income (PY) which individuals wish to carry in cash and demand deposits or the ratio of money stock to income, P is that the price level, and Y is that the aggregate real income. This equation tells us that “other things being equal, the demand for money in normal terms would be proportional to the nominal level of income for every individual, and hence for the mixture economy also.”

Its Critical Evaluation:

This approach includes time and saving deposits and other convertible funds within the demand for money. It also stresses the importance of factors that make money more or less useful, like the costs of holding it, uncertainty about the future then on. But it says little about the character of the relationship that one expects to prevail between its variables, and it doesn't say too much about which ones could be important.

One of its major criticisms arises from the neglect of store useful function of cash. The classicists emphasized only the medium of exchange function of money which simply acted as a go-between to facilitate buying and selling. For them, money performed a neutral role within the economy. It had been barren and wouldn't multiply, if stored within the form of wealth.

This was an erroneous view because money performed the “asset” function when it's transformed into other sorts of assets like bills, equities, debentures, real assets (houses, cars, TVs, then on), etc. Thus the neglect of the asset function of cash was the main weakness of classical approach to the demand for money which Keynes remedied.

The Keynesian Approach: Liquidity Preference:

Keynes in his General Theory used a replacement term “liquidity preference” for the demand for money. Keynes suggested three motives which led to the demand for money in an economy: (1) the transactions demand, (2) the precautionary demand, and (3) the speculative demand.

The Transactions Demand for Money:

The transactions demand for money arises from the medium of exchange function of money in making regular payments for goods and services. Consistent with Keynes, it relates to “the need of money for the present transactions of private and business exchange” it's further divided into income and business motives. The income motive is supposed “to bridge the interval between the receipt of income and its disbursement.”

Similarly, the business motive is supposed “to bridge the interval between the time of incurring business costs which of the receipt of the sale proceeds.” If the time between the incurring of expenditure and receipt of income is little, less cash are going to be held by the people for current transactions, and the other way around. There’ll, however, be changes within the transactions demand for money depending upon the expectations of income recipients and businessmen. They depend on the level of income, the rate of interest, the business turnover, the traditional period between the receipt and disbursement of income, etc.

Given these factors, the transactions demand for money may be a direct proportional and positive function of the extent of income, and is expressed as

L1 = kY

Where L1 is that the transactions demand for money, k is that the proportion of income which is kept for transactions purposes, and Y is that the income.

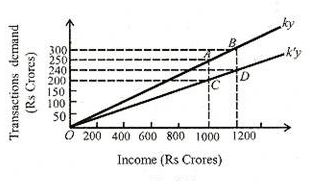

This equation is illustrated in Figure below where the line kY represents a linear and proportional relation between transactions demand and therefore the level of income. Assuming k= 1/4 and income Rs 1000 crores, the demand for transactions balances would be Rs 250 crores, at point A. With the rise in income to Rs 1200 crores, the transactions demand would be Rs 300 crores at point В on the curve kY.

If the transactions demand falls because of a change in the institutional and structural conditions of the economy, the value of к is reduced to mention, 1/5, and therefore the new transactions demand curve is kY. It shows that for income of Rs 1000 and 1200 crores, transactions balances would Rs 200 and 240 crores at points С and D respectively within the figure. “Thus we conclude that the chief determinant of changes within the actual amount of the transactions balances held is changes in income. Changes within the transactions balances are the results of movements along a line like kY instead of changes within the slope of the line. Within the equation, changes in transactions balances are the results of changes in Y instead of changes in k.”

Interest Rate and Transactions Demand:

Regarding the rate of interest because the determinant of the transactions demand for money Keynes made the LT function interest inelastic. But the acknowledged that the “demand for money within the active circulation is additionally the some extent a function of the rate of interest, since a higher rate of interest may cause a more economical use of active balances.” “However, he didn't stress the role of the rate of interest during this a part of his analysis, and lots of of his popularizes ignored it altogether.” In recent years, two post-Keynesian economists William J. Baumol and James Tobin have shown that the rate of interest is a crucial determinant of transactions demand for money.

They have also pointed out the relationship, between transactions demand for money and income isn't linear and proportional. Rather, changes in income result in proportionately smaller changes in transactions demand.

Transactions balances are held because income received once a month isn't spent on the same day. In fact, a private spreads his expenditure evenly over the month. Thus some of cash meant for transactions purposes are often spent on short-term interest-yielding securities. It’s possible to “put funds to figure for a matter of days, weeks, or months in interest-bearing securities like U.S. Treasury bills or commercial paper and other short-term money market instruments.

The problem here is that there's a cost involved in buying and selling. One must weigh the financial cost and inconvenience of frequent entry to and exit from the market for securities against the apparent advantage of holding interest-bearing securities in situ of idle transactions balances.

Among other things, the value per purchase and sale, the speed of interest, and therefore the frequency of purchases and sales determine the profitability of switching from ideal transactions balances to earning assets. Nonetheless, with the value per purchase and sale given, there's clearly some rate of interest at which it becomes profitable to modify what otherwise would be transactions balances into interest-bearing securities, albeit the amount that these funds could also be spared from transactions needs is measured only in weeks. The higher the rate of interest , the larger will be the fraction of any given amount of transactions balances which will be profitably diverted into securities.”

The structure of cash and short-term bond holdings is shown in Figure below (A), (B) and (C). Suppose a private receives Rs 1200 as income on the first of every month and spends it evenly over the month. The month has four weeks. His saving is zero.

Accordingly, his transactions demand for money in each week is Rs 300. So he has Rs 900 idle money within the first week, Rs 600 within the second week, and Rs 300 within the third week. He will, therefore, convert this idle money into interest bearing bonds, as illustrated in Panel (B) and (C) of Figure. He keeps and spends Rs 300 during the first week (shown in Panel B), and invests Rs 900 in interest-bearing bonds (shown in Panel C). On the primary day of the second week he sells bonds worth Rs. 300 to cover cash transactions of the second week and his bond holdings are reduced to Rs 600.

Similarly, he will sell bonds worth Rs 300 within the beginning of the third and keep the remaining bonds amounting to Rs 300 which he will sell on the first day of the fourth week to satisfy his expenses for the last week of the month. The amount of cash held for transactions purposes by the individual during each week is shown in saw-tooth pattern in Panel (B), and therefore the bond holdings in each week are shown in blocks in Panel (C) of Figure

The modern view is that the transactions demand for money is a function of both income and interest rates which may be expressed as

L1 = f (Y, r).

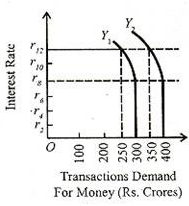

This relationship between income and rate of interest and therefore the transactions demand for money for the economy as an entire is illustrated in Figure 3. We saw above that LT = kY. If y=Rs 1200 crores and k= 1/4, then LT = Rs 300 crores.

This is shown as Y1 curve in Figure below. If the income level rises to Rs 1600 crores, the transactions demand also increases to Rs 400 crores, given k = 1/4. Consequently, the transactions demand curve shifts to Y2. The transactions demand curves Y1, and Y2 are interest- inelastic so long because the rate of interest doesn't rise above r8 per cent.

As the rate of interest starts rising above r8, the transactions demand for money becomes interest elastic. It indicates that “given the cost of switching into and out of securities, a rate of interest above 8 per cent is sufficiently high to draw in some amount of transaction balances into securities.” The backward slope of the K, curve shows that at still higher rates, the transaction demand for money declines.

Thus when the rate of interest rises to r12, the transactions demand declines to Rs 250 crores with an income level of Rs 1200 crores. Similarly, when the value is Rs 1600 crores the transactions demand would decline to Rs 350 crores at r12 rate of interest. Thus the transactions demand for money varies directly with the level of income and inversely with the speed of interest.

The Precautionary Demand for Money

The Precautionary motive relates to “the desire to produce for contingencies requiring sudden expenditures and for unforeseen opportunities of advantageous purchases.” Both individuals and businessmen keep take advantage reserve to satisfy unexpected needs. Individuals hold some cash to supply for illness, accidents, unemployment and other unforeseen contingencies.

Similarly, businessmen keep cash in reserve to tide over unfavourable conditions or to gain from unexpected deals. Therefore, “money held under the precautionary motive is very like water kept in reserve during a water tank.” The precautionary demand for money depends upon the level of income, and business activity, opportunities for unexpected profitable deals, availability of cash, the cost of holding liquid assets in bank reserves, etc.

Keynes held that the precautionary demand for money, like transactions demand, was a function of the extent of income. But the post-Keynesian economists believe that like transactions demand, it's inversely associated with high interest rates. The transactions and precautionary demand for money are going to be unstable, particularly if the economy isn't at full employment level and transactions are, therefore, but the maximum, and are liable to fluctuate up or down.

Since precautionary demand, like transactions demand may be a function of income and interest rates, the demand for money for these two purposes is expressed within the single equation LT=f(Y, r)9. Thus the precautionary demand for money also can be explained diagrammatically in terms of Figures 2 and three.

The Speculative Demand for Money:

The speculative (or asset or liquidity preference) demand for money is for securing profit from knowing better than the market what the longer term will bring forth”. Individuals and businessmen having funds, after keeping enough for transactions and precautionary purposes, wish to make a speculative gain by investing fettered. Money held for speculative purposes may be a liquid store of value which may be invested at an opportune moment in interest-bearing bonds or securities.

Bond prices and therefore the rate of interest are inversely associated with one another. Low bond prices are indicative of high interest rates, and high bond prices reflect low interest rates. A bond carries a fixed rate of interest. As an example, if a bond of the worth of Rs 100 carries 4 per cent interest and therefore the market rate of interest rises to eight per cent, the worth of this bond falls to Rs 50 within the market. If the market rate of interest falls to 2 per cent, the value of the bond will rise to Rs 200 within the market.

This can be figured out with the assistance of the equation

V = R/r

Where V is that the current market value of a bond, R is that the annual return on the bond, and r is that the rate of return currently earned or the market rate of interest. So a bond worth Rs 100 (V) and carrying a 4 per cent rate of interest (r), gets an annual return (R) of Rs 4, that is,

V=Rs 4/0.04=Rs 100. When the market rate of interest rises to 8 per cent, then V=Rs 4/0.08=Rs50; when it fall to 2 per cent, then V=Rs 4/0.02=Rs 200.

Thus individuals and businessmen can gain by buying bonds worth Rs 100 each at the market value of Rs 50 each when the rate of interest is high (8 per cent), and sell them again once they are dearer (Rs 200 each when the speed of interest falls (to 2 per cent).

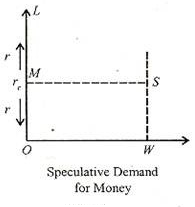

According to Keynes, it's expectations about changes in bond prices or within the current market rate of interest that determine the speculative demand for money. In explaining the speculative demand for money, Keynes had a normal or critical rate of interest (rc) in mind. If the present rate of interest (r) is above the “critical” rate of interest, businessmen expect it to fall and bond price to rise. They will, therefore, buy bonds to sell them in future when their prices rise so as to realize thereby. At such times, the speculative demand for money would fall. Conversely, if the present rate of interest happens to be below the critical rate, businessmen expect it to rise and bond prices to fall. They will, therefore, sell bonds within the present if they have any, and therefore the speculative demand for money would increase.

Thus when r > r0, an investor holds all his liquid assets in bonds, and when r < r0 his entire holdings enter money. But when r = r0, he becomes indifferent to carry bonds or money.

Thus relationship between an individual’s demand for money and therefore the rate of interest is shown in Figure below where the horizontal axis shows the individual’s demand for money for speculative purposes and therefore the current and important interest rates on the vertical axis. The figure shows that when r is larger than r0, the asset holder puts all his cash balances in bonds and his demand for money is zero.

This is illustrated by the LM portion of the vertical axis. When r falls below r0, the individual expects more capital losses on bonds as against the interest yield. He, therefore, converts his entire holdings into money, as shown by OW within the figure. This relationship between an individual asset holder’s demand for money and therefore the current rate of interest gives the discontinuous step demand for money curve LMSW.

For the economy as an entire the individual demand curve are often aggregated on this presumption that individual asset-holders differ in their critical rates r0. It’s smooth curve which slopes downward from left to right, as shown in Figure below.

Thus the speculative demand for money is a decreasing function of the rate of interest. The higher the rate of interest, the lower the speculative demand for money and therefore the lower the rate of interest, the higher the speculative demand for money. It are often expressed algebraically as Ls = f (r), where Ls is that the speculative demand for money and r is that the rate of interest.

Geometrically, it's shows in above Figure. The figure shows that at a very high rate of interest rJ2, the speculative demand for money is zero and businessmen invest their cash holdings fettered because they believe that the rate of interest cannot rise further. Because the rate of interest falls to say, r8 the speculative demand for money is OS. With a further fall within the rate of interest to r6, it rises to OS’. Thus the form of the Ls curve shows that because the rate of interest rises, the speculative demand for money declines; and with the fall in the rate of interest, it increases. Thus the Keynesian speculative demand for money function is very volatile, depending upon the behaviour of interest rates.

Liquidity Trap:

Keynes visualised conditions during which the speculative demand for money would be highly or maybe totally elastic so that changes within the quantity of money would be fully absorbed into speculative balances. This is often the famous Keynesian liquidity trap. During this case, changes within the quantity of money have no effects in the least on prices or income. According to Keynes, this is often likely to happen when the market rate of interest is very low in order that yields on bond, equities and other securities also will be low.

At a really low rate of interest, like r2, the Ls curve becomes perfectly elastic and therefore the speculative demand for money is infinitely elastic. This portion of the Ls curve is known as the liquidity trap. At such a low rate, people prefer to keep money in cash instead of invest fettered because purchasing bonds will mean a definite loss. People won't buy bonds so long as the rate of interest remain at the low level and that they will be expecting the speed of interest to return to the “normal” level and bond prices to fall.

According to Keynes, because the rate of interest approaches zero, the risk of loss in holding bonds becomes greater. “When the price of bonds has been bid up so high that the rate of interest is, say, only 2 per cent or less, a really small decline within the price of bonds will wipe out the yield entirely and a rather further decline would result in loss of the a part of the principal.” Thus the lower the rate of interest, the smaller the earnings from bonds. Therefore, the greater the demand for cash holdings. Consequently, the Ls curve will become perfectly elastic.

Further, consistent with Keynes, “a long-term rate of interest of two per cent leaves more to fear than to hope, and offers, at an equivalent time, a running yield which is only sufficient to offset a really small measure of fear.” This makes the Ls curve “virtually absolute within the sense that almost everybody prefers cash to holding a debt which yields so low a rate of interest.”

Prof. Modigliani believes that an infinitely elastic Ls curve is possible in a period of great uncertainty when price reductions are anticipated and therefore the tendency to invest in bonds decreases, or if there prevails “a real scarcity of investment outlets that are profitable at rates of interest above the institutional minimum.”

The phenomenon of liquidity trap possesses certain important implications.

First, the monetary authority cannot influence the rate of interest even by following a cheap money policy. a rise within the quantity of cash cannot lead to a further decline within the rate of interest during a liquidity-trap situation. Second, the rate of interest cannot fall to zero.

Third, the policy of a general wage cut can't be efficacious within the face of a perfectly elastic liquidity preference curve, like Ls in above figure. No doubt, a policy of general wage cut would lower wages and prices, and thus release money from transactions to speculative purpose, the rate of interest would remain unaffected because people would hold money due to the prevalent uncertainty within the money market. Last, if new money is made, it instantly goes into speculative balances and is put into bank vaults or cash boxes rather than being invested. Thus there's no effect on income. Income can change with none change in the quantity of money. Thus monetary changes have a weak effect on economic activity under conditions of absolute liquidity preference.

The Total Demand for Money:

According to Keynes, money held for transactions and precautionary purposes is primarily a function of the extent of income, LT=f (F), and therefore the speculative demand for money may be a function of the rate of interest, Ls = f (r). Thus the total demand for money may be a function of both income and therefore the interest rate:

LT + LS = f (Y) + f (r)

Or L = f (Y) + f (r)

Or L=f (Y, r)

Where L represents the entire demand for money.

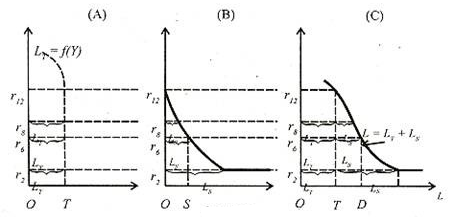

Thus the entire demand for money can be derived by the lateral summation of the demand function for transactions and precautionary purposes and therefore the demand function for speculative purposes, as illustrated in Figure below (A), (B) and (C). Panel (A) of the Figure shows ОТ, the transactions and precautionary demand for money at Y level of income and different rates of interest. Panel (B) shows the speculative demand for money at various rates of interest. It’s an inverse function of the rate of interest.

For instance, at r6 rate of interest it's OS and as the rate of interest falls to r the Ls curve becomes perfectly elastic. Panel (C) shows the entire demand curve for money L which may be a lateral summation of LT and Ls curves: L=LT+LS. For example, at rb rate of interest, the entire demand for money is OD which is that the sum of transactions and precautionary demand ОТ plus the speculative demand TD, OD=OT+TD. At r2 rate of interest, the total demand for money curve also becomes perfectly elastic, showing the position of liquidity trap.

Friedman’s restatement of Demand for money

Milton Friedman in his essay – “The Quantity Theory of Money—A Restatement” (1956). In his restatement he asserts that “ the quantity theory is in the first instance a theory demand for money. It is not a theory of output, or of money income, or of price level”. The demand for money may be from the ultimate wealth owning units. For them money is one kind of asset, one way of holding wealth and it is identical with demand for a consumption services i.e. holding the money gives utility to the consumer. Money is also demanded by the productive enterprises, for them money is a capital good, a source of productive services that are combined with other productive services to yield the product that the enterprises sell. Friedman analysed that wealth can be held in numerous form and affected by same factor as the demand for other asset

a) Total wealth (permanent income)

b) relative return on asset(which incorporate risk)

c) The taste and preference of wealth owning units

According to Friedman wealth can be held in different forms and analyzed 5 of them :—money ,Bond ,Equities , Physical non – human goods ,human capital. Each form of wealth has a unique characteristic of its own and a different yield either explicitly in the form of interest, dividend, labour income or implicitly in the form of services of money measured in terms of P, and inventories.

1. Money: It include currency, demand deposit, and time deposit which yields interest on deposits.

2. Bonds: It is a claim to a time stream of payment that are fixed in nominal units

3. Equities: It is a claim to time stream of payment that are fixed in real units.

4. Physical Non- Human goods : These are inventories of producers and consumer durable.

5. Human Capital: It is the productive capacity of human beings.

The Present discounted value of these expected flows from these five form of wealth constitute the current value of wealth expressed as: W=y/r. Here W represent the current value of total wealth and r is the rate of interest. This equation shows that wealth is a capitalised income.

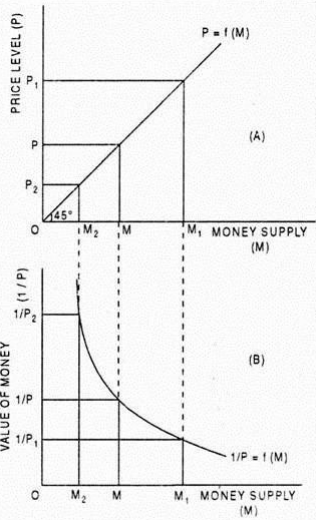

Friedman expresses Demand function for money for an individual wealth holder as

Where, Md//P =real money balances

W = fraction of wealth in non- human form

Rm =rate of return on money

Rb = rate of return on bond

Re =rate of return on equity

µ = any variable other than income which may affect utility attached to the service of money

= expected rate of change in prices of goods

= expected rate of change in prices of goods

Features of Friedman Demand for money:

1. Friedman treated money as one type of asset, in which wealth holders can keep a part of their wealth

2. According to him, demand for real money balance (Md/P) is directly related to permanent income(Y) and indirectly related to returns from bonds, stock(equities), and goods and expected rate of inflation.

3. Income Elasticity of demand for money is greater than unity.

4. In the long-run demand for money function is stable and is relatively interest- inelastic.

Key takeaways –

- The desire for demand for money arises because of three motives: Transaction motive, Precautionary motive, Speculative motive.

- According to Friedman wealth can be held in different forms and analyzed 5 of them :—money ,Bond ,Equities , Physical non – human goods ,human capital

Quantity theory of money

Definition

Quantity theory of money states that money supply and price level in an economy are in direct proportion to one another. When there is a change in the supply of money, there is a proportional change in the price level and vice-versa.

Quantity Theory of Money is supported and calculated by using the Fisher Equation by American economist Irving Fisher.

M*V= P*T

Where,

- M = Money supply

- V = Velocity of money

- P = Price level

- T = volume of the transactions

Fisher’s equation of exchange

The transactions version of the quantity theory of money was provided by the American economist Irving Fisher in his book- The Purchasing Power of Money (1911). According to Fisher, “Other things remaining unchanged, as the quantity of money in circulation increases, the price level also increases in direct proportion and the value of money decreases and vice versa”.

Equation

MV = PT or P = MV/T

The value of money or the price level is also determined by the demand and supply of money.

- Supply of money (MV) –

The supply of money consists of the quantity of money in existence (M) multiplied by the velocity of money (V), i.e., the number of times this money changes hands. In Fisher’s equation, V is the transactions velocity of money which means the average number of times a unit of money turns over or changes hands to execute transactions during a period of time.

Thus, the total volume of money in circulation during a period of time refers to MV. Since for transaction purposes money is only to be used, total supply of money also forms the total value of money expenditures in all transactions in the economy during a period of time.

2. Demand for money (PT) –

Money is demanded for transaction purposes, but not for its own sake. The demand for money is equal to the total market value of all goods and services transacted. It is determined by multiplying total amount of things (T) by average price level (P).

Thus, Fisher’s equation of exchange represents equality between the supply of money or the total value of money expenditures in all transactions and the demand for money or the total value of all items transacted.

Supply of money = Demand for Money

MV = PT

Or

P = MV/T

Where,

- M is the quantity of money

- V is the transaction velocity

- P is the price level.

- T is the total goods and services transacted.

The equation states that MV = PT, the fact that the actual total value of all money expenditures (MV) always equals the actual total value of all items sold (PT).

To develop the classical quantity theory of money Irving Fisher used the equation of exchange i.e., a causal relationship between the money supply and the price level.

The transactions approach to the quantity theory of money maintains that, there exists a direct and proportional relation between M and P; if the quantity of money is doubled, the price level will also be doubled and the value of money halved; if the quantity of money is halved, the price level will also be halved and the value of money doubled.

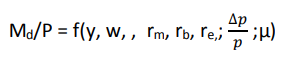

(i) In first Figure, when the money supply is doubled from OM to OM1, the price level is also doubled from OP to OP1. When the money supply is halved from OM to OM2, the price level is halved from OP to OP2. Price curve, P = f(M), is a 45° line showing a direct proportional relationship between the money supply and the price level.

(ii) In second Figure, when the money supply is doubled from OM to OM1; the value of money is halved from O1/P to O1/P1 and when the money supply is halved from OM to OM2, the value of money is doubled from O1/P to O1/P2. The value of money curve, 1/P = f (M) is a rectangular hyperbola curve showing an inverse proportional relationship between the money supply and the value of money.

Assumptions of the theory

- According to Fisher, the velocity of money (V) is constant and is not influenced by the changes in the quantity of money.

- Total volume of trade or transactions (T) is also assumed to be constant and is not affected by changes in the quantity of money.

- P is passive factor in the equation of exchange which is affected by the other factors.

- The quantity theory of money assumed money only as a medium of exchange.

- The theory is based on the assumption of long period. Over a long period of time, V and T are considered constant.

Criticism

- Unrealistic assumption of full employment – In the actual world full employment is a rare phenomenon. Less than full employment and not full employment is a normal feature in a modern capitalist economy. According to Keynes, as long as there is unemployment, every increase in money supply leads to a proportionate increase in output, thus leaving the price level unaffected.

- Static theory - The quantity theory assumes that the values of Vand T remain constant. But, these variables do not remain constant in reality. The assumption of these factors constant makes the theory a static theory and is inapplicable in the dynamic world.

- Simple truism - The equation of exchange (MV = PT) is a mere truism and proves nothing. It is simply a factual statement which reveals that the amount of money paid in exchange for goods and services (MV) is equal to the market value of goods and services received (PT). The equation does not tell anything about the causal relationship between money and prices.

- Technical inconsistency – This equation is considered as technically inconsistent by prof. Halm. M in the equation is a stock concept; it refers to the stock of money at a point of time. V, on the other hand, is a flow concept, it refers to velocity of circulation of money over a period of time, M and V are non-comparable factors and cannot be multiplied together.

- Ignores other determinants of price level - The quantity theory maintains that price level is determined by the factors included in the equation of exchange, i.e. by M, V and T. It ignores the importance of many other determinates of prices, such as income, expenditure, investment, saving, consumption, population, etc.

- No discussion of velocity of money - The concept of velocity of circulation of money is not discussed in the quantity theory of money, nor does it throw light on the factors influencing it. It regards the velocity of money to be constant and thus ignores the variation in the velocity of money to occur in the long period.

- One sided theory - Fisher’s transactions approach is one- sided. It assumes the demand for money to be constant and takes into consideration only the supply of money and its effects. It ignores the role of demand for money in causing changes in the value of money.

Key takeaways –

- The general price level in a country is determined by the supply of and the demand for money.

- Given the demand for money, changes in money supply lead to proportional changes in the price level.

- The monetary authorities, by changing the supply of money, can influence and control the price level and the level of economic activity of the country.

Cambridge cash balance approach

As an alternative to Fisher’s quantity theory of money, Marshall, Pigou, Robertson, Keynes, etc. at the Cambridge University formulated the Cambridge cash-balance approach. Fisher’s transactions approach emphasized the medium of exchange functions of money. On the other hand, the Cambridge cash-balance approach was based on the store of value function of money.

According to cash-balance approach, the value of money is determined by the demand for money and supply of money. This approach, considers the demand for money and supply of money at a particular moment of time. Since, at a particular moment the supply of money is fixed, it is the demand for money which largely accounts for the changes in the price level. As such, the cash-balance approach is also called the demand theory of money.

Robertson wrote in this connection: “Money is only one of the many economic things. Its value, therefore, is primarily determined by exactly nomic things. Its value, therefore, is primarily determined by exactly the same two factors as determine the value of any other thing, namely, the conditions of demand for it, and the quantity of it available.”

The supply of money is determined at a point of time by the banking system. On the other hand the demand for money is the demand to hold cash balance for transactions and precautionary motives. Thus the cash balances approach considers the demand for money as a store of value and not as a medium of exchange

The Cambridge equations show that given the supply of money at a point of time, the value of money is determined by the demand for cash balances.

When the demand for money increases, people in order to have larger cash holdings will reduce their expenditures on goods and services. Reduced demand for goods and services will bring down the price level and raise the value of money. On the contrary, fall in the demand for money will raise the price level and lower the value of money.

The Cambridge cash balances equations of Marshall, Pigou, Robertson and Keynes are discussed as under:

Marshalls equation

MV = KPY or P = M/KY

Where,

- M is the supply of money (currency plus demand deposits)

- P is the price level,

- Y is aggregate real income; and

- K is the fraction of the real income which the people desire to hold in the form of money.

The price level (P) is directly proportional to the money supply (M)

The price level (P) is indirectly proportional to the aggregate real income (Y) and the proportion of the real income which people desire to keep in the form of money (K)

M and Y being constant, with the increase in K price level (P) falls and with the decreases in K price level (P) rises

K and Y remaining unchanged, if supply of money (M) increases, price level (P) rises and if supply of money (M) decreases, price level (P) falls.

Pigou’s equation

P = M/KR

Where

- P is the purchasing power of money or the value of money

- k is the proportion of total real resources or income (R) which people wish to hold in the form of titles to legal tender,

- R is the total resources or real income, and

- M refers to the number of actual units of legal tender money.

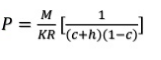

Since money is held by the community in the form of cash and in the form of bank deposits. In order to include bank notes and bank balances in the demand for money, Pigou modifies his equation as

Where

- c =the proportion of cash which people keep with them

- 1–c =the proportion of bank balances held by the people

- h =the proportion of cash reserves to deposits held by the banks.

According to Pigou, K was more significant than M in explaining changes in the purchasing power of money (value of money). This means that the value of money depends upon the demand of the people to hold money. Moreover, assuming K and R (and also c and h in the modified equation) to be constant, the relationship between money supply (M) and price level (P) is direct and proportional.

Robertson’s equation

M = KPT or P = M/KT

Where,

- P = the price level;

- M = the money supply;

- T = the total amount of goods and services to be purchased during a year.

- K = the proportion of T which people wish to hold in the form cash.

According to Robertson’s cash balance equation, P changes directly with M and inversely with K and T.

Keynes’s Equation

n = pk or p = n/k

Where

- n = the cash held by the general public;

- p = the price level of consumer goods;

- k = the real balance or the proportion of consumer goods over which cash is kept.

Assuming K to be constant, a change in ‘n’ causes a direct and proportional change in ‘p’. In other words, if the quantity of money in circulation is doubled the price level will also be doubled, provided k remains constant.

This equation can be expanded by taking into account bank deposits.

n = p (k+ rk’)

Where, r is the cash reserve ratio of the banks; k’ is the real balance held in the form of bank money.

Again, if k, k’ and r are constant, p will change in exact proportion to the change in n.

Criticisms of the Cash Balance Approach:

- Truisms: The cash balances equations are truisms, like the transaction equation. Take any Cambridge equation: Marshall’s P=M/kY or Pigou’s P=kR/M or Robertson’s P=M/kT or Keynes’s p=n/k, it establishes a proportionate relation between quantity of money and price level.”

- More importance to total deposit - Another defect of the Cambridge equation “lies in its applying to the total deposits considerations which are primarily relevant only to the income-deposits.” And the importance attached to k “is misleading when it is extended beyond the income deposits.”

- Neglect other factors - The cash balances equation does not tell about changes in the price level due to changes in the of income, business and savings purposes.

- Neglect of savings investment effect – Cash balance approach fails to analyse variations in the price level due to saving-investment inequality in the economy.

- K and Y are not constant – this equation assumes k and Y as constant like transaction equation. This is unrealistic because during short period it is not essential that the cash balances (k) and the income of the people (Y) should remain constant.

- Neglects interest rate – The cash balance approach ignores interest rate that have significant influence upon the price level. The theory fails to integrate rate of interest, investment, output, employment and income with the theory of vale and output.

Key takeaways –

- Cash-balance approach states that the value of money depends upon the demand for money and the demand for money arises on account of its being a store of value.

Inflation is a rate of change in the price level. The rate of change is measured with reference to the base year so that a long term perspective is obtained with regard to price rise. For all practical purposes, inflation rate is measured on yearly basis. However, in recent years, the inflation rate is also measured on monthly and weekly basis. The rate of inflation can be measured as: P = (P - P0)/P0 *100

Demand pull inflation

Definition

Demand-pull inflation exists when aggregate demand for a good or service exceeds aggregate supply. It starts with an increase in consumer demand. Sellers meet such an increase with more supply. But when additional supply is unavailable, sellers raise their prices. That results in demand-pull inflation.

When there is excess demand in the economy, producers are able to raise prices and achieve bigger profit margins because they know that demand is running ahead of supply. Typically, demand-pull inflation becomes a threat when an economy has experienced a strong boom with GDP rising faster than the long run trend growth of potential GDP.

Demand pull inflation takes place due to rise in aggregate demand. Aggregate demand may rise due to combined effect of higher demand from the various sectors of the economy such as the firms, households and the government. According to Keynes, inflation arises when there is an inflationary gap in the economy. Inflationary gap arises when aggregate demand is greater than aggregate supply at full employment level of output. Keynes explained inflation in terms of demand pull forces. When the economy is operating at the full employment level of output, supply cannot increase in response to increase in demand and hence prices rise.

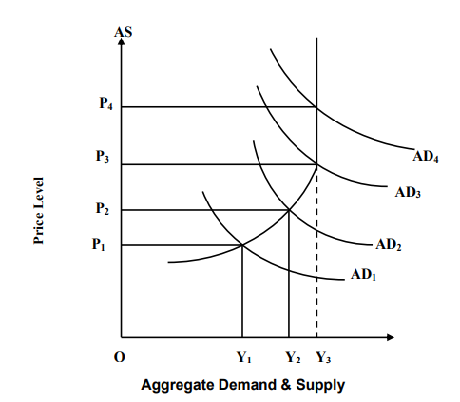

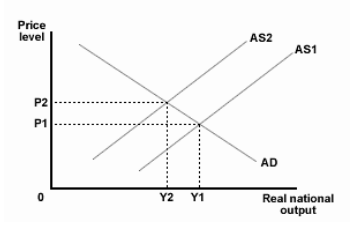

Demand pull inflation is depicted in the above. It is observed that aggregate demand and supply curves are measured along the X-axis and the general price level is measured along the Y-axis. The aggregate supply curve AS rises upward in the beginning and becomes vertical when full employment level of output is achieved at point OYf. This is because the supply of output cannot be increased once full employment level of output is achieved. When the aggregate demand curve is AD1, the equilibrium is less than full employment level and the price level OP1 is determined. When aggregate demand increases to AD2, the price level rises to OP2 due to excess demand at price level OP1. Since the economy is operating at less than full employment level, the real sector of the economy responds to rise in prices and hence the output increases to OY2. When the aggregate demand further rises to AD3, the price level rises to OP3 followed by increase in output to OYf. When the aggregate demand further rises to AD4, the aggregate supply does not respond to remain constant at OYf and only the price level rises to OP4. After the full employment level of output the aggregate supply curve becomes perfectly inelastic and parallel to the Y-axis.

Causes of demand pull inflation

- Growing economy – When the families spend more instead of savings and feel confident to take more debt. They expect better jobs and rise. This leads to a steady increase in demand, which means higher prices.

- Expectation of inflation – Once people expect inflation in future, they tend to buy more to avoid higher prices. This leads to increase in demand and creates demand-pull inflation. It’s difficult to eradicate once the expectation of inflation sets in.

- Over expansion of the money supply – This happens when too much money chasing too few goods. An expansion of the money supply with too few goods to buy makes prices increase.

- Discretionary fiscal policy - According to Keynesian economic theory, government spending drives up demand. Demand increases when government lowers taxes. When consumers have more discretionary income to spend on goods and services it creates inflation.

- Strong brand - Marketing can create high demand for certain products, a form of asset inflation. This leads to charge high prices

- Technological innovation – A company owns the market when it creates new technology until other companies figure out how to copy it. People demand new technology that creates real improvement in their daily lives.

Cost push inflation

Cost-push inflation occurs when supply costs rise or supply levels fall. As long as demand remains the same either will drive up prices. Cost push inflation is created by Shortages or cost increases in labor, raw materials, and capital goods.

Definition

Cost-push inflation occurs when firms respond to rising costs by increasing prices in order to protect their profit margins.

Under costpush inflation, price rise due to rise in the cost of raw materials and wages. Sometimes, some producers or workers may raise the prices of their products above the level which prevails in the market. It has been seen that during recession period aggregate demand decrease than supply then prices should also decrease but it did not happen. The cost-push inflation is caused by monopoly which is created by some monopoly groups of the society. It has been seen in the society that labour unions succeed in their demand for higher wages from the industries. Higher wages leads to increase in prices thus is creates wage push inflation which is a part of cost push inflation. Not only labour unions but monopolistic and oligopolistic also increase their profit margin and increase the prices which is known as profit push inflation. Similarly, there can be supply shock inflation

The above diagram shows cost-Push inflation, here AD shows to aggregate demand and AS shows aggregate supply. Is there is increase in AS1 to AS2 then GDP will move from Y1 to Y2 and prices will increase from P1 to P2. This will leads to inflation in the economy. Thus, it can be concluded that cost of factor of production also push inflation in the economy and excess demand is not only a reason for inflation.

Causes of cost push inflation

- Monopoly- Cost- Push inflation are created by companies that achieve a monopoly over an industry. A monopoly reduces supply to meet its profit goal.

- Wage inflation - Wage inflation is created when workers have enough leverage to force through wage increases. When people expect higher inflation wage may increase in order to protect their real incomes.

- Component cost – It involves increase in the prices of raw materials and other components. This is due to the rise in commodity prices such as oil, copper and agricultural products used in food processing.

- Higher indirect taxes – Government regulation and taxation may reduce the supply of many other products such as rise in the duty on alcohol, fuels and cigarettes, or a rise in Value Added Tax.

- Exchange rates - Higher import prices happens when any country that allows the value of its currency to fall. The foreign supplier does not want the value of its product to drop along with that of the currency. It can raise the price and keep its profit margin intact, if demand is inelastic.

Effect of inflation

- Effects on distribution of income and wealth - Within the national economy, the impact of inflation is felt unevenly by the different groups of individuals

- Creditors and debtors - During inflation creditors lose as they receive the repayments during a period of low prices. On other hand, debtors during inflation gain, since they repay their debts in currency that has lost its value

- Producers and workers - Producers gain during inflation as they get higher prices and leads to earn more profits from the sale of their products. Producers can earn more during inflation, as the rise in prices is usually higher than the increase in costs. But, workers lose because there is a fall in their real wages as their money wages do not usually rise proportionately with the increase in prices.

- Fixed income earners – during inflation, fixed income earners suffer greatly because inflation reduces the value of their earnings.

- Investors – in equity shares investor gains s they get dividends at higher rates. But the bondholders lose because they get a fixed interest on the real value of which has already fallen

- Farmers – farmers gains during inflation as rise in the price of agricultural products is higher than the rise in the price of other goods

- Effects on production - The production of all goods—both of consumption and of capital goods is stimulated by rising prices. As producers get more and more profit, they try to produce more and more by utilizing all the available resources at their disposal. The production cannot increase after the stage of full employment as all the resources are fully employed.

- Effects on income and employment - On account of larger spending and greater production inflation tend to increase the aggregate money income (i.e., national income) of the community as a whole. Similarly, under the impact of increased production the volume of employment increases. Whereas people real income of the fails to increase proportionately due to a fall in the purchasing power of money.

- Effects on business and trade – During inflation due to higher income, greater productivity and larger spending the aggregate volume of internal trade tend to increase. On account of rise in the price of domestic goods export trade is likely to suffer. Profit soar during inflation as cost do not rise as fast as price.

- Effects on the government finance - During inflation, the government revenue increases as it gets more revenue from income tax, sales tax, excise duties, etc. in the same way, public expenditure increases as the government is required to spend more and more for administrative and other purposes. But the real burden of public debt is reduced due to rising prices because a fix sum has to be paid in installment per period.

- Effects on Growth - A mild inflation promotes economic growth, but a increase in inflation hinder the economic growth as it raises cost of development projects. Although in a developing economy mild dose of inflation is inevitable and desirable, a high rate of inflation tends to lower the growth rate by slowing down the rate of capital formation and creating uncertainty.

Nature of inflation in a developing economy

Developing countries have often found themselves in the grip of inflation in their bid to raise the standards of living of their people through development plans.

But the nature of inflation in developing economies is quite different from that found in developed countries. True inflation starts after the level of full-employment is attained in developed countries. But in developing countries countries like India huge unemployment and inflation exist side by side. This is because during times of depression the nature of unemployment in developing countries differs from that which prevails in developed countries.

The governments in advanced countries take various steps to increase the level of investment in order to get the economy out of depression. Increase in investment and effective demand helps a great deal in removing depression and unemployment which are caused by the lack of effective demand. Thus, when the supply of output can be increased easily so as to match increase in effective demand, there need be no inflationary pressures.

The situation in developing countries is different. Unemployment in under-developed economics is not due to lack of effective demand hut due to the lack of real capital. In these countries, by accumulating more real capital level of national income can be increased and the unemployment can be removed. Increase in the capital formation requires stepping up the level of investment.

Now, developing countries are making huge investment expenditure to increase the rate of capital formation and thus to obtain rapid economic growth.

Policy measure to curb inflation

Monetary policy

Meaning

Monetary policy is the process of drafting, announcing, and implementing the plan of actions taken by the central bank, currency board, or other competent monetary authority of a country that controls the quantity of money in an economy and the channels by which new money is supplied.

Monetary policy aims at meeting macroeconomics objectives such as controlling inflation, consumption, growth, and liquidity which consist of the management of money supply and interest rates. This is achieved by actions such as modifying the interest rate, buying or selling government bonds, regulating foreign exchange (forex) rates, and changing the amount of money banks are required to maintain as reserves.

Definition

Monetary policy, the demand side of economic policy, refers to the actions undertaken by a nation's central bank to control money supply and achieve macroeconomic goals that promote sustainable economic growth.

Johnson defines monetary policy “as policy employing central bank’s control of the supply of money as an instrument for achieving the objectives of general economic policy.”

G.K. Shaw defines it as “any conscious action undertaken by the monetary authorities to change the quantity, availability or cost of money.”

Objectives

- Full employment - The foremost objectives of monetary policy is full employment. It is an important goal not only because unemployment leads to wastage of potential output, but also because of the loss of social standing and self-respect.

- Price stability – One of the objectives of monetary policy is to stabilize the price level. This policy is favored because fluctuations in prices bring uncertainty and instability to the economy.

- Economic growth – In the recent years the most important objectives of monetary policy has been the rapid economic growth of an economy. Economic growth is defined as “the process whereby the real per capita income of a country increases over a long period of time.”

- Balance of payment – Another important objective is to maintain equilibrium in the balance of payments.

Instruments of monetary policy

- Bank rate policy – The minimum lending rate is the bank rate of the central bank at which it rediscounts first class bills of exchange and government securities held by the commercial banks. Central banks raise the bank rate when it finds that inflationary pressures have started emerging within the economy. Commercial bank borrows less as borrowing from central bank become costly. In turn, commercial banks raise their lending rate to the business community and the borrowers borrow less from commercial bank.

On the other hand central banks lower the bank rate when prices are depressed. On the part of commercial bank it is cheap to borrow from the central bank. The commercial bank lowers their lending rate and encourages business men to borrow more.

2. Open market operation – Open market operations refer to sale and purchase of securities in the money market by the central bank. The central bank sells securities, when prices are rising and there is need to control them. The reserves of commercial banks are reduced and they are not in a position to lend more to the business community.

On the contrary, the central bank buys securities, when recessionary forces start in the economy. The commercial bank reserves are raised and they lend more to the business community.

3. Changes in reserves ratio – Every bank is required to keep certain percentage of its total deposits with the central bank. The central bank raise the reserve ratio when prices are rising. Banks are required to keep more with the central bank. Their reserves are reduced and they lend less. In the opposite case, the reserves of commercial banks are raised, when the reserve ratio is lowered. They lend more and the economic activity is favorably affected.

4. Selective credit controls - For particular purposes selective credit controls are used to influence specific types of credit. The central bank raises the margin requirement when there is brisk speculative activity in the economy or in particular sectors in certain commodities and prices start rising. The result is that the borrowers are given less money in loans against specified securities. In case of recession in a particular sector, the central bank encourages borrowing by lowering margin requirements.

Fiscal policy

Monetary policy alone cannot handle the business cycles. Compensatory fiscal policy should therefore be applied to it. During a boom, fiscal controls are highly effective in reducing excessive government spending, personal spending on consumption, and private and public expenditure. On the other hand, during a crisis, they help to increase government spending, personal consumption spending, and private and public expenditure.

During Boom: The government tries to reduce unnecessary spending on non-development programs during a boom in order to reduce the demand for goods and services. This is also helpful to check private spending but it is very difficult the government expenditure. Further, it is difficult to find essential and non-essential activities. Therefore, government comes with taxation system. The government is raising the rates of personal, corporate and commodity taxes to cut personal spending.

The government frequently follows the policy of having a budget surplus when government revenues are higher than expenditures. This is achieved by increasing tax rates or reducing government expenditures or both. It tends to reduce sales and aggregate demand through the reverse process of multiplier. Another budgetary step that is usually taken is to borrow more from the economy that has the effect of reducing the supply of money with the public. Therefore, the servicing of public debt should be suspended and deferred to some future date when the economy stabilizes.

During Depression: In this stage government raise public spending, lowers taxes, and adopts a policy of budget deficit. Such policies tend to increase aggregate demand, production, profits, employment and prices. An increase in public expenditure would raise the aggregate demand for goods and services and it will lead to higher income through the multiplier. Public expenditure includes construction of roads, canals, dams, parks, schools, hospitals, and other construction works. This will create demand for the labour in the market. The government is also increasing its spending on welfare programs such as unemployment insurance and other social security initiatives to raise demand for consumer goods industries.

Direct control

Major objective of direct control is to ensure proper allocation of resources for price stability in the economy. They are intended to affect the economy's strategic points and they impact particular consumer and producers. These are in the form of licensing rationing, price and wage controls, export taxes, currency caps, quotas, monopoly regulation, etc. They are more effective in addressing inflationary pressure bottlenecks and shortages. Its success depends on an effective and fair administration being in place. Otherwise it will lead to black marketing, coercion, long queues, speculation, and so on.

Inflation targeting

Definition

Inflation targeting is a central banking policy that revolves around adjusting monetary policy to achieve a specified annual rate of inflation. The principle of inflation targeting is based on the belief that long-term economic growth is best achieved by maintaining price stability, and price stability is achieved by controlling inflation.

Based on above-target or under-target inflation an inflation-targeting central bank can boost or lower interest rates, respectively. The ideology is that rising interest rates typically cools the economy to hold during inflation; lowering interest rates generally speeds up the economy and thus increases inflation.

Inflation targeting allows central banks to respond to shocks to the domestic economy and focus on domestic considerations. Stable inflation reduces investor uncertainty, allows investors to predict changes in interest rates, and anchors inflation expectations. If the target is published, inflation targeting also allows for greater transparency in monetary policy.

Benefits

- Inflation targeting allows monetary policy to “focus on domestic considerations and to respond to shocks to the domestic economy”, which is not possible under a fixed-exchange-rate system.

- Transparency is another key benefit of inflation targeting. Central banks in developed countries that have successfully implemented inflation targeting tend to “maintain regular channels of communication with the public”.

- An explicit numerical inflation target increases a central bank’s accountability, and thus it is less likely that the central bank falls prey to the time-inconsistency trap. This accountability is especially significant because even countries with weak institutions can build public support for an independent central bank.

Key takeaways –

- Inflation targeting is a central bank strategy of specifying an inflation rate as a goal and adjusting monetary policy to achieve that rate.

Case study

Controlling Inflation without Hurting Growth

T he expected spread of food price inflation in India to more industrial categories has provoked a crescendo of calls for sharp monetary tightening. Such a response would be appropriate if excess demand were driving inflation.

But the current high Wholesale Price Index (WPI) inflation follows prolonged cost shocks and a period of very low inflation. This low base overstates inflation. Policy should rather reduce inflationary expectations without hurting the supply response.

Supply Response

The supply response is especially important since India is in a catch-up growth phase. Investment is occurring to relieve specific bottlenecks.

Data from India’s Central Statistical Organisation (CSO) shows that fixed investment has remained above pre-crisis levels of 32 per cent of GDP. There is a sharp rise in the production of capital goods. Continuing high investment implies there cannot be a large excess of demand over capacity. Good growth and sales help spread manufacturing costs. If productivity rises, the price-line can be held. A good monsoon after a bad one should see a sharp jump in agricultural production and softening of food prices. Inflation in primary articles will fall from this month onwards because of the base effect and manufactured goods inflation from November.

But wages and commodity prices are pushing up costs. Sustained high food price inflation raises wages, since food is still above 50 per cent of the average consumer basket. That procurement prices have held steady this year, after excessive hikes in the past few years, will provide some relief.

But over the longer term, structural measures, such as better infrastructure and empowering more private initiatives, are required to improve agricultural supply response. That the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGA) has raised rural wages is a good thing, but the emphasis has been on employment and not productivity, although it has the potential to raise both.

A wage rise exceeding that in agricultural productivity raises food prices. Or else rupee appreciation is required to let wages rise without inflation. Prices normally are sticky downwards. So, with monetary accommodation, a relative price change raises the general price level. What goes up doesn’t readily come down except for commodities. But in India administered prices impart an upward bias even for food and fuel.

The petrol price decontrol was required — prices will now be free to fall as well as rise. But the timing of the price rise, when inflation is dangerously high, is unfortunate.

Past oil price hikes have not led to sustained inflation because they either followed or led to severe monetary tightening. The attempt to conserve the Macro Economic stimulus can be consistent with falling inflation only if it enables a supply response.

Post-reform India has had loose fiscal and tight monetary policy. Direct subsidies created hidden indirect costs and raised debt. But inflation harms electoral prospects, so instead of inflating debt away, a severe monetary tightening would be imposed. There would be a large sacrifice of output, but little reduction in chronic cost-driven inflation

Fiscal Consolidation

The government now seems to be trying a better combination: Imposing fiscal consolidation so monetary policy can be more accommodative. Lower debt, deficits and interest rates are useful attributes for a more open economy to have. But rather than raise tax rates that push up prices and costs, a better approach to fiscal consolidation is to reduce wasteful government expenditure. Plugging leakages and cutting allocations in areas where budgets have not been spent would create better incentives to spend.

The government has a poor record in spending effectively. Tax revenues have started rising again with growth, but this boom should not be squandered like the last one. The contribution of economic growth was 55 per cent and of spending cuts was 35 per cent to Canada’s successful deficit reduction in the 1990s.

Monetary Policy

A sharp rise in interest rates has severe consequences. We saw the collapse in industry following such a rise in the late 1990s and in July 2008. Policy should rather follow a path of gradual rise in interest rates conditional on inflation. The knowledge of future rise will reduce inflationary expectations, if combined with action to reduce costs.

A short-term nominal exchange rate appreciation reduces costs. This can be very useful to contain a temporary spike in oil or food prices and will become more effective as petrol prices are free and food prices reflect border prices. Today, the price of Washington apples determines that of Indian apples.

The current depreciation runs counter to the attempt to reduce inflation. Changing one exchange rate prevents thousands of nominal price changes that then become sticky and persist, requiring painful prolonged adjustment. Small steps give the freedom to respond to evolving circumstances. But to walk with baby steps one must start early and coordinate action over several fronts.

News

Sources-

- Business economics by H.L Ahuja.

- Business economics application and analysis by Dr. Raj kumar.

- Business economics by T Aryamala.

- Business economics by SK Agarwal.