UNIT – 4

THE SALE OF GOODS ACT-1930

Case study (Bengal Corporation Private Ltd. v/s The State Of Madras on 29 September, 1964)

It is a contract for the supply of 3,055.57 tons of M.S. Sheets subject to certain specified conditions, to the Integral Coach Factory, Madras. The preamble to the contract states that the contract is in regard to the import of 3,055.57 tons of M.S. Sheets from the Continent against the invitation to the tender for the Integral Coach Factory, Madras, by the Ministry of Heavy Industries, Iron & Steel Control, Government of India. The first condition under the heading "quality" provides that the materials must be manufactured by the process as stipulated in the specifications mentioned, against each size in the schedule attached. Cast number must be stamped on each piece or in metal tags attached to each bundle. Inspection test certificate must accompany each consignment. The second clause regarding price states that the price shall be C.I.F. Madras as per schedule. The price would include all extras for quality, size, packing, guarantee for durability etc. Clause 3 provides that shipment of the entire tonnage as promised must be completed by December 1957 commencing from June 1957. In the case of failure to ship the materials in full within the aforesaid date, and unless the Iron and Steel Controller is satisfied that the failure was due to reasons beyond the control of the importers, the Government of India will be entitled to recover from the seller a sum of 2 per cent. for every week or part thereof as liquidated damages. The Government of India also reserved the right to purchase elsewhere without notice to the seller, on his account and at his risk and cost, such materials as had not been shipped within the above date. The seller had to submit to the Iron and Steel Controller advance information of all expected shipments of steel indicating the name of the vessel, the port of arrival and the categories and quantities of steel. Under clause 4 under the heading "delivery" the materials as soon as they were received in the jetty (of the harbour) should be delivered ex-jetty to the Deputy Controller of Stores, Integral Coach Factory, Madras, and no demurrage incurred at the port upto the point of landing would be reimbursed by the consignee. In Clause 5 under the heading "inspection and its charges" it is stated that the materials shall be inspected by the D.G.I., S.D., London, and the inspecting officers shall have the right to be present during all stages of manufacture and shall be afforded all reasonable facilities for satisfying themselves that the materials are being manufactured in accordance with the specifications laid down in the schedule attached. Inspection charges for the inspector nominated by the Iron and Steel Controller shall be paid by the seller in the first instance and will be reimbursed later by the consignee. In clause 6 under the heading "payment" it is stated that on completion of delivery of each consignment, the seller will submit his 100 per cent. bill at full landed cost, based on the C.I.F. price to the Deputy Controller of Stores. (The, seller was also required to intimate the name of the manufacturers to the Director-General of Inspection, Supplies and Disposals, London, for the inspection, of the Stores. The schedule gives the specifications that the sheets should be of Siemsn Martin manufacture.

A. CONCEPT

DEFINITION:

As per Sec 4(1) of the Indian Sale of Goods Act, 1930 defines the contract of sale of goods in the following manner:

“A contract of sale of goods is a contract whereby the seller transfers or agrees to transfer the property in goods to the buyer for a price”.

B. ESSENTIALS ELEMENTS OF CONTRACT OF SALE

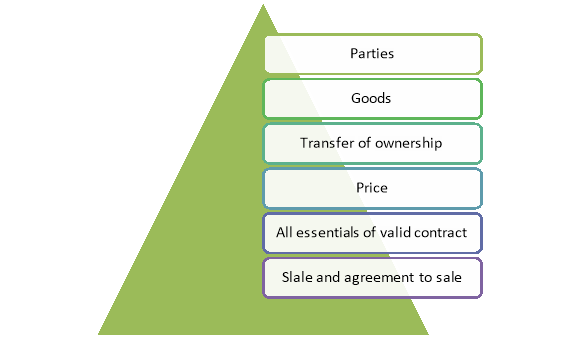

The following six features/elements are essential elements of any contract of sale of goods.

Figure: Essential elements of contract of sale

1. Two Parties:

A contract of sale of goods is bilateral in nature wherein property within the goods has got to pass from one party to a different. One cannot buy one’s own goods. For example, A is that the owner of a grocery shop. If he supplies the goods (from the stock meant for sale) to his family, it doesn't amount to a sale and there's no contract of sale. This is often so because the vendor and buyer must be two different parties, together person can't be both a seller also as a buyer. However, there shall be a contract of sale between part owners. Suppose A and B jointly own a tv set, A may transfer his ownership within the tv set to B, thereby making B the only owner of the goods. Within the same way, a partner may buy goods from the firm during which he's a partner, and vice-versa. However, there's an exception against the overall rule that nobody should purchase his own goods. Where a pawnee sells the goods pledged with him/her on non-payment of his/her money, the pawnor may buy them in execution of a decree.

2. Goods:

The topic matter of a contract of sale must be goods. All kinds of movable property except actionable claims and money are considered ‘goods’. Contracts concerning services aren't considered as contract of sale. Immovable property is governed by a separate statute, ‘Transfer of Property Act’.

3. Transfer of ownership:

Transfer of property in goods is additionally integral to a contract of sale. The term ‘property in goods’ means the ownership of the goods. In every contract of sale, there should be an agreement between the buyer and therefore the seller for transfer of ownership. Here property means the overall property in goods, and not merely a special property. Thus, it's the overall property, which is transferred under a contract of sale as distinguished from special property, which is transferred just in case of pledge of goods, i.e., possession of goods is transferred to the pledgee or pawnee while the ownership rights remain with the pledger. Thus, during a contract of sale there must be an absolute transfer of the ownership. It must be noted that the physical delivery of products isn't essential for transferring the ownership.

4. Price:

The customer must pay some price for goods. The term ‘price’ is ‘the money consideration for a purchase of goods’. Accordingly, consideration during a contract of sale has necessarily to be in money. Where goods are offered as consideration for goods, it'll not amount to sale, but it'll be called barter or exchange, which was prevalent in past. Similarly, if an individual offers the goods to somebody else inconsiderately, it amounts to a present or charity and not sale. In explicit terms, goods must be sold for a particular amount of cash, called the worth. However, the consideration is often partly in money and partly in valued up goods. Furthermore, payment isn't necessary at the time of creating the contract of sale.

5. All essentials of a valid contract:

A contract of sale may be a special form of contract, therefore, to be valid, it must have all the essential elements of a valid contract, viz., free consent, consideration, competency of contracting parties, lawful object, legal formalities to be completed, etc. A contract of sale is going to be invalid if important elements are missing. as an example , if A agreed to sell his car to B because B forced him to try and do so by means of undue influence, this contract of sale isn't valid since there's no free consent on the a part of the transferor.

6. Includes both a ‘Sale’ and ‘An Agreement to Sell’:

The ‘contract of sale’ may be a generic term and includes both sale and an agreement to sell. The sale is an executed or absolute contract whereas ‘an agreement to sell’ is an executory contract and implies a conditional sale. A contract of sale is often made merely by an offer, to buy or sell goods for a price, followed by acceptance of such an offer. Interestingly, neither the payment of price nor the delivery of goods is important at the time of creating the contract of sale unless otherwise agreed. Subject to the provisions of the law for time being effective, a contract of sale could also be made either orally or in writing, or partly orally and partly in writing, or may even be implied from the conduct of the parties.

C. DISTINGUISHED BETWEEN “SALE” AND “AGREEMENT TO SELL”

The points of distinction between a sale and an agreement to sell are:

Sl no | SALE | AGREEMENT TO SELL |

| Ownership remains with the buyer | Ownership remains with the seller |

2. Execution | It is a executed contract | It is a executor contract |

3. Risk | Risk of loss falls on the buyer | Risk of loss falls on the seller |

4. Sale to third party | Seller cannot resell the goods | Seller can sell goods to third party |

5. Goods | It can be in case of existing and specific goods | It can be in case of future and unascertained goods |

6. Right to sue | In case of breach of a contract, seller can sue for the price of the goods | In case of breach of a contract, seller can sue only for damages not for the price |

7. Remedy for insolvency | The seller is only entitled to the ratable dividend of the price due if the buyer becomes insolvent | The seller may refuse to sell the goods to the buyer w/o payments if the buyer becomes insolvent |

D. DISTINGUSH BETWEEN SALE AND HIRE PURCHASE AGREEMENT

The main points of distinction between the ‘sale’ and ‘hire-purchase’ are as follows:

1. In a sale, property within the goods is transferred to the customer immediately at the time of contract, whereas in hire-purchase, the property within the goods passes to the hirer upon payment of the last installment.

2. In a sale, the position of the customer is that of the owner of the goods but in hire purchase, the position of the hirer is that of a bailee till he pays the last installment

3. Within the case of a sale, the customer cannot terminate the contract and is sure to pay the price of the goods. On the other hand, within the case of hire-purchase, the hirer may, if he so likes, terminate the contract by returning the products to its owner with none liability to pay the remaining installments.

4. Within the case of a sale, the vendor takes the danger of any loss resulting from the insolvency of the customer. Within the case of hire purchase, the owner takes no such risk, for if the hirer fails to pay an installment, the owner has the proper to require back the goods.

5. Within the case of a sale, the customer can pass an honest title to a bonafide purchaser from him but during a hire-purchase, the hirer cannot pass any title even to a bonafide purchaser.

6. In a sale, sales tax is levied at the time of the contract whereas during a hire-purchase, sales tax isn't leviable until it eventually ripens into a sale

E. GOODS

According to section 7 of the Sale of goods act, 1930 'Goods' means every kind of moveable property and includes stock and shares, growing crops, grass, and things attached to or forming part of the land, which are agreed to be severed before sale or under the contract of sale. Thus, goods include every kind of moveable property other than actionable claim or money. Example - goodwill, copyright, trademark, patents, water, gas, and electricity are all goods and may be the subject matter of a contract of sale.

TYPES OF GOODS

Goods may be classified as-

1. Existing goods [section 6(1)]:

Goods which are physically in existence and which are in seller's ownership and/or possession, at the time of entering the contract of sale are called 'existing goods.' Where seller is the owner, he has the general property in them. For example, A sale land to B for cash.

2. Future goods [section 6(3)]:

Goods to be manufactured, produced or acquired by the seller after the making of the contract of sale are called 'future goods' These goods may be either not yet in existence or be in existence but not yet acquired by the seller. Example, A agrees to sell to B all the milk that his cow may yield during the coming year. This is a contract for the sale of future goods.

3. Contingent goods [Sec. 6 (2)]:

Though a type of future goods, these are the goods the acquisition of which by the seller depends upon a contingency, which may or may not happen.

Example- A agrees to sell to B a specific rare painting provided he is able to purchase it from its present owner. This is a contract for the sale of contingent goods.

F. EFFECTS OF DESTRUCTION OF GOODS - ALREADY CONTRACTED (AS PER SECTION 6,7,8)

There are various sorts of goods and therefore the parties have various options to agree about the delivery of the goods. The effects of destruction of goods are-

A. CONCEPT

MEANING OF CONDITION

Sec 12(2) of Sales of Goods Act, 1930 has defined Condition as: “A condition is a stipulation essential to the main purpose of the contract, the breach of which gives rise to a right to treat the contract as repudiated”.

(a) Which is essential to the main purpose of the contract?

(b) The breach of which gives the aggrieved party a right to terminate the contract.

Example:-

By charter party( a contract by which a ship is hired for the carriage of goods), it was agreed that ship m of 420 tons “now in port of Amsterdam” should proceed direct to new port to load a cargo. In fact at the time of the contract the ship was not in the port of Amsterdam and when the ship reached Newport, the charterer refused to load. Held, the words “now in the port of Amsterdam” amounted to a condition, the breach of which entitled the charterer to repudiate the contract.

WARRANTY

Sec 12(3) of Sale Of Goods Act, 1930 has defined Warranty as : “A warranty is a stipulation collateral to the main purpose of the contract, the breach of which gives rise to only claim for damages but not to a right to reject the goods and treat the contract as repudiated”.

B. DISTINCTION BETWEEN CONDITION AND WARRANTY

Sl no. | CONDITION | WARRANTY |

1. | A condition is a stipulation (in a contract), which is essential to the main purpose of the contract. | A warranty is a stipulation, which is only collateral or subsidiary to the main purpose of the contract. |

2. | A breach of condition gives the aggrieved party a right to sue for damages as well as the right to repudiate the contract. | A breach of warranty gives only the right to sue for damages. The contract cannot be repudiated. |

3. | A breach of condition may be treated as a breach of warranty in certain circumstances. | A breach of warranty cannot be treated as a breach of condition |

C. IMPLIED CONDITIONS AND WARRANTIES (TYPES)

1. Implied undertaking as to title, etc. (sec. 14)—

In a contract of sale, unless the circumstances of the contract are such as to show a different intention, there is—

(a) an implied condition on the part of the seller that, in the case of a sale, he has a right to sell the goods and that, in the case of an agreement to sell, he will have a right to sell the goods at the time when the property is to pass;

(b) an implied warranty that the buyer shall have and enjoy quiet possession of the goods;

(c) an implied warranty that the goods shall be free from any charge or encumbrance in favour of any third party not declared or known to the buyer before or at the time when the contract is made.

2. Sale by description (sec. 15)

Where there is a contract for the sale of goods by description, there is an implied condition that the goods shall correspond with the description; and, if the sale is by sample as well as by description, it is not sufficient that the bulk of the goods corresponds with the sample if the goods do not also correspond with the description.

3. Implied conditions as to quality or fitness (sec 16)

Subject to the provisions of this Act and of any other law for the time being in force, there is no implied warranty or condition as to the quality or fitness for any particular purpose of goods supplied under a contract of sale, except as follows:—

(a) Where the buyer, expressly or by implication, makes known to the seller the particular purpose for which the goods are required, so as to show that the buyer relies on the seller’s skill or judgment, and the goods are of a description which it is in the course of the seller’s business to supply (whether he is the manufacturer or producer or not), there is an implied condition that the goods shallbe reasonably fit for such purpose: Provided that, in the case of a contract for the sale of a specified article under its patent or other trade name, there is no implied condition as to its fitness for any particular purpose.

(b) Where goods are bought by description from a seller who deals in goods of that description (whether he is the manufacturer or producer or not), there is an implied condition that the goods shall be of merchantable quality:

(c) An implied warranty or condition as to quality or fitness for a particular purpose may be annexed by the usage of trade.

(d) An express warranty or condition does not negative a warranty or condition implied by this Act unless inconsistent therewith.

D. THE DOCTRINE OF CAVEAT EMPTOR

The doctrine of caveat emptor is an integral a part of the Sale of goods Act. It translates to “let the customer beware”. This suggests it lays the responsibility of their choice on the customer themselves. It is specifically defined in Section 16 of the act “there is not any implied warranty or condition on the standard or the fitness for any particular purpose of goods supplied under such a contract of sale“ A seller makes his goods available within the open market. The buyer previews all his options then accordingly makes his choice. Now let’s assume that the product seems to be defective or of inferior quality. This doctrine says that the vendor won't be liable for this. The customer himself is liable for the choice he made. So the doctrine attempts to form the customer more aware of his choices. It’s the duty of the customer to see the standard and therefore the usefulness of the product he's purchasing. If the product seems to be defective or doesn't live up to its potential the vendor won't be liable for this.

For example, A bought a horse from B. A wanted to enter the horse during a race seems the horse wasn't capable of running a race on account of being lame. But A didn't inform B of his intentions. So B won't be liable for the defects of the horse. The Doctrine of principle will apply.

However, the customer can shift the responsibility to the vendor if the three following conditions are fulfilled.

• If the customer shares with the vendor his purpose for the acquisition

• The buyer relies on the knowledge and/or technical expertise of the seller

• And the vendor sells such goods

EXCEPTIONS TO THE DOCTRINE OF CAVEAT EMPTOR

The doctrine of caveat emptor has certain specific exceptions.

1] Fitness of Product for the Buyer’s Purpose

When the customer informs the vendor of his purpose of buying the goods, it's implied that he's counting on the seller’s judgment. It’s the duty of the seller then to ensure the goods match their desired usage.

Say for instance: A goes to B to shop for a bicycle. He informs B he wants to use the cycle for mountain trekking. If B sells him a standard bicycle that's incapable of fulfilling A’s purpose the vendor are going to be responsible. Another example is that the case study of Priest v. Last.

2] Goods Purchased under brand name

When the customer buys a product under a brand name or a branded product the seller can't be held liable for the usefulness or quality of the product. So there's no implied condition that the goods are going to be fit the aim the customer intended.

3] Goods sold by Description

When the customer buys the products based only on the outline there'll be an exception. If the goods don't match the outline then in such a case the vendor are going to be liable for the goods.

4] Goods of Merchantable Quality

Section 16 (2) deals with the exception of merchantable quality. The sections state that the vendor who is selling goods by description features a duty of providing goods of merchantable quality, i.e. capable of passing the market standards. So if the products aren't of marketable quality then the customer won't be the one who is responsible. It’ll be the seller’s responsibility. However if the customer has had an inexpensive chance to look at the product, then this exception won't apply.

5] Sale by Sample

If the customer buys his goods after examining a sample then the rule of Doctrine of principle won't apply. If the remainder of the goods don't resemble the sample, the customer can't be held responsible. During this case, the vendor is going to be the one responsible. For example, A places an order for 50 toy cars with B. He checks one sample where the car is red the remainder of the cars end up orange. Here the doctrine won't apply and B is going to be responsible.

6] Sale by Description and Sample

If the sale is completed via a sample also as an outline of the product, the customer won't be responsible if the goods don't resemble the sample and/or the outline. Then the responsibility will fall squarely on the vendor.

7] Usage of Trade

There is an implied condition or warranty about the standard or the fitness of goods/products. But if a seller deviated from this then the rules of caveat emptor cease to use. For instance, A bought goods from B in an auction of the contents of a ship. But B didn't inform A the contents were sea damaged, and then the rules of the doctrine won't apply here.

8] Fraud or Misrepresentation by the seller

This is another important exception. If the seller obtains the consent of the customer by fraud then caveat emptor won't apply. Also if the vendor conceals any material defects of the goods which are later discovered on closer examination but the customer won't be responsible. In both cases, the vendor is going to be the guilty party.

A. CONCEPT

In general sense, property is any physical or virtual entity that's owned by a private or jointly by a gaggle of people. An owner of the property has the proper. Human life isn't possible without property. It’s economic, socio-political, sometimes religious and legal implications. It’s the legal domain, which institutes the thought of ownership. The basic postulate of the thought is that the exclusive control of a private over some ‘thing’. Here the foremost important aspect of the concept of ownership and property is that the word ‘thing’, on which an individual has control to be used to consume, sell, rent, mortgage, transfer and exchange his property. Property is any physical or intangible entity that's owned by an individual or jointly by a group of people depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property has the proper to consume, sell, rent, mortgage, transfer, exchange or destroy their property, and/or to exclude others from doing this stuff .

There are some Traditional principles associated with property rights which includes include:

1. Control over the use of the property.

2. Right to require any enjoy the property.

3. Right to transfer or sell the property.

4. Right to exclude others from the property.

Definition of property

There are different definitions are given in several act as per there uses and wishes. But within the most vital act which exclusively talks about the property and rights associated with property transfer of property act 1882 has no definite definition of the term property. But it's defined in another act as per their use and wish. Those definitions are as follows:

Section 2(c) of the Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act, 1988 defines property as: “Property” means property of any kind, whether movable or immovable, tangible or intangible, and includes any right or interest in such property.

Section 2 (11) of the Sale of excellent Act, 1930 defines property as: “Property” means the overall property in goods, and not merely a special property.

B. RULES OF TRANSFER OF PROPERTY (AS PER SECTION 19-26)

A sale of goods or property implies a transfer or passing of ownership to the buyer. The passing of property is a crucial aspect to assist determines the liabilities and rights of both the buyer and therefore the seller. Once a property is passed to the buyer, then the danger within the goods sold is that of the customer and not the seller. This is often true even if the products are within the possession of the seller.

a) Goods must be ascertained (sec. 18)— Where there is a contract for the sale of unascertained goods, no property in the goods is transferred to the buyer unless and until the goods are ascertained.

b) Property passes when intended to pass (se. 19)

(1) Where there is a contract for the sale of specific or ascertained goods the property in them is transferred to the buyer at such time as the parties to the contract intend it to he transferred.

(2) For the purpose of ascertaining the intention of the parties regard shall be had to the terms of the contract, the conduct of the parties and the circumstances of the case.

(3) Unless a different intention appears, the rules contained in sections 20 to 24 are rules for ascertaining the intention of the parties as to the time at which the property in the goods is to pass to the buyer.

c) Specific goods in a deliverable state (sec. 20)

Where there is an unconditional contract for the sale of specific goods in a deliverable state, the property in the goods passes to the buyer when the contract is made, and it is immaterial whether the time of payment of the price or the time of delivery of the goods, or both, is postponed.

d) Specific goods to be put into a deliverable state (sec.21)

Where there is a contract for the sale of specific goods and the seller is bound to do something to the goods for the purpose of putting them into a deliverable state, the property does not pass until such thing is done and the buyer has notice thereof.

d) Specific goods in a deliverable state, when the seller has to do anything thereto in order to ascertain price (sec. 22)

Where there is a contract for the sale of specific goods in a deliverable state, but the seller is bound to weigh, measure, test or do some other act or thing with reference to the goods for the purpose of ascertaining the price, the property does not pass until such act or thing is done and the buyer has notice thereof.

e) Sale of unascertained goods and appropriation (sec.23)

(1) Where there is a contract for the sale of unascertained or future goods by description and goods of that description and in a deliverable state are unconditionally appropriated to the contract, either by the seller with the assent of the buyer or by the buyer with the assent of the seller, the property in the goods thereupon passes to the buyer. Such assent may be express or implied, and may by given either before or after the appropriation is made.

(2) Where, in pursuance of the contract, the seller delivers the goods to the buyer or to a carrier or other bailee (whether named by the buyer or not) for the purpose of transmission to the buyer, and does not reserve the right of disposal, he is deemed to have unconditionally appropriated the goods to the contract.

f) Goods sent on approval or “on sale or return”(sec, 24)

When goods are delivered to the buyer on approval or “on sale or return” or other similar terms, the property therein passes to the buyer—

(a) when he signifies his approval or acceptance to the seller or does any other act adopting the transaction;

(b) if he does not signify his approval or acceptance to the seller but retains the goods without giving notice of rejection, then, if a time has been fixed for the return of the goods, on the expiration of such time, and, if no time has been fixed, on the expiration of a reasonable time.

g) Sale by person not the owner (sec. 27)

Subject to the provisions of this Act and of any other law for the time being in force, where goods are sold by a person who is not the owner thereof and who does not sell them under the authority or with the consent of the owner, the buyer acquires no better title to the goods than the seller had, unless the owner of the goods is by his conduct precluded from denying the seller’s authority to sell:

Provided that, where a mercantile agent is, with the consent of the owner, in possession of the goods or of a document of title to the goods, any sale made by him, when acting in the ordinary course of business of a mercantile agent, shall be as valid as if he were expressly authorised by the owner of the goods to make the same; provided that the buyer acts in good faith and has not at the time of the contract of sale notice that the seller has not authority to sell.

h) Sale by one of joint owners (sec. 28)

If one of several joint owners of goods has the sole possession of them by permission of the co-owners, the property in the goods is transferred to any person who buys them of such joint owner in good faith and has not at the time of the contract of sale notice that the seller has not authority to sell

A. CONCEPT

A seller of goods is deemed to be an unpaid seller when:-

CONDITIONS:

B. RIGHTS OF AN UNPAID SELLER

Right of lien, right of stoppage in transit, right of resale

Right of lien (sec.47-49)

Right of stoppage of goods in transit (sec.50-52)

(i) Seller must have parted with the possession of goods i.e., the goods must not be in the possession of the seller

(ii) The goods must be in course of transit

(iii) Buyer must have become insolvent

Right of resale (sec.54)

An unpaid seller can resell the goods under the following circumstances:

Where the goods are of a perishable nature

C. REMEDIES FOR BREACH OF CONTRACT OF SALE ( AS PER SECTION 55-61)

The Sale of goods Act, 1930 was enacted because the law concerning the sale of goods under the Indian Contract Act was considered to be inadequate. Here attention has been drawn to the remedies available to either party for breach of the contract of sale by the other. Chapter VI of the Sale of goods Act, 1930 relates to breach of contract and lays down the rights and liabilities of the vendor unto the customer and the other way around. Sections 55 to 61 affect this.

Sections 55 and 56 specialise in seller’s remedies against the customer and entitle the vendor to either sue for price of the goods or invite damages for non-performance of the contract. Sections 57, 58 and 59 lay down the remedies available to the customer against the seller within the event the latter breaches the contract. The buyer can seek damages for non-delivery of goods, damages for breach of warranty or performance of the contract. Sections 60 and 61 produce to those special situations wherein a remedy for breach is out there to both the buyer and seller.”

A. Seller’s remedies against buyer

The suits which will be instituted by the seller against the buyer under the Act are often roughly divided into two types

1. Suit for Price.

2. Damages for non-acceptance.

i. Suit for Price.

Section 55

(1) Where under a contract of sale the property within the goods has passed to the buyer and therefore the buyer wrongfully neglects or refuses to buy the goods consistent with the terms of the contract, the vendor may sue him for the worth of the goods.

(2) Where under a contract of sale the worth is payable on each day certain regardless of delivery and therefore the buyer wrongfully neglects or refuses to pay such price, the seller may sue him for the worth although the property within the goods has not passed and therefore the goods haven't been appropriated to the contract.

From the above section, it are often seen that except as provided by sub-section (2), the vendor can only sue for the payment when the property has passed to the buyer. The passing of the property depends upon certain conditions, and if these conditions aren't fulfilled, he cannot sue for the payment under this section.

Where goods are sold for a specific amount and therefore the payment has got to be made partly in cash and partly in a similar way, the default if made in a similar way entitles the vendor to sue for the rest of the worth.

ii. Damages for non-acceptance

Section 56

Where the buyer wrongfully neglects or refuses to simply accept and buy the goods, the vendor may sue him for damages for non-acceptance.

The damages are assessed on the idea of the principles contained in sections 73 and 74 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872. consistent with section 73 of the Indian Contract Act, when a contract has been broken, the party who suffers by the breach is entitled to receive, from the party who has broken the contract, compensation for any loss caused to him thereby, which naturally arose, within the usual course of things from such a breach, or which the parties knew once they entered into the contract, to be likely to result from the breach of it.

Furthermore, in estimating the loss or damage caused by a breach of contract, the means which existed of remedying the inconvenience caused by the non-performance of the contract must be taken under consideration.

The date at which the market value is to be ascertained is that the day on which the contract need to are performed by delivery and acceptance as fixed by the contract or, where no time is fixed, at the time of the refusal to perform.

By virtue of the provisions of sections 55 and 63 of the Indian Contract Act, where the time for the performance is fixed by the contract but it's extended and another date substituted for it by agreement between the parties, the substituted date must be taken because the date for ascertaining the measure of damages.

Where the products are deliverable by installments and therefore the buyer has got to accept one or the opposite or all the installments, the difference in prices is to be reckoned with on the day that a specific installment was to be delivered.

Where the military authorities refused to simply accept further supplies of cots in breach of their contract, the J&K high court allowed Rs. 4 per cot because the damages to the supplies because the profit which the supplier would have earned under his contract of supply.

It has been seen that the vendor has various remedies against both the goods and therefore the buyer personally, and in many cases where those remedies exist he still has the choice of availing himself of the remedy declared by this section ; but where the property has not passed and there's nothing within the contract which enables him to resell the products and charge the customer with the difference between the contract price, and therefore the price realized on the resale, or to sue for the price regardless of delivery, or the passing of the property, the remedy provided by this section is that the only remedy by which he can recover pecuniary compensation for the buyer’s breach of contract.

B. Buyer’s remedies against the seller

The suits which will be instituted by the customer against the seller are often roughly divided into three types

1. Damages for Non- Delivery (Section 57)

Where the seller wrongfully neglects or refuses to deliver the goods to the buyer, the buyer may sue the seller for damages for non-delivery. When the property within the goods has passed, the buyer, as long as he's entitled to the immediate possession, has all the remedies of an owner against people who affect the goods during a manner inconsistent together with his rights. If, therefore, the seller wrongfully re-sells them, he may sue the vendor in trover, and also against the second buyer, though as against him the rights could also be hamper by the provisions in sections 30 and 54. In the case of non-delivery, truth measure of damages are going to be the difference between the contract price and therefore the market value at the time of the breach. The market price of the goods means “the value within the market, independently of any circumstances peculiar to the plaintiff (the buyer)”

Where he, the seller, is guilty of breach of an agreement to sell, the subsequent remedies could also be available to the buyer:

(i) the customer may sue for damages for non-delivery under section 57 of the Sale of goods Act

(ii) just in case the worth has been paid by the buyer, he may recover it during a suit for money had and received for a consideration which has totally failed.

Where however the buyer has did not prove the alleged damages caused thanks to short supply of goods by seller and has also not served to seller a notice under Section 55 of the Indian Contracts Act, the buyer cannot claim damages.

In the case of pre-payment, the date for ascertaining the measure of damages must be the date of the breach, though it'd be said in such a case, the customer has not got the cash in his hands and can't therefore enter the market and buy; and in conformity with this concept it's been ruled at nisi prius that the date of the trial could also be taken. However a more rational view is that even during this case the date of breach should be taken to calculate the difference between the contract price and therefore the sale price, and therefore the buyer can recover this amount, alongside an interest.

2. Remedy for Breach of Warranty (Section 59)

(i) Where there's a breach of warranty by the seller, or where the buyer elects or is compelled to treat any breach of a condition on the a part of the seller as a breach of warranty, the customer isn't by reason only of such breach of warranty entitled to reject the goods; but he may-

(a) found out against the seller the Brach of warranty in diminution or extinction of the price; or

(b) Sue the seller for damages for breach of warranty.

(ii) The very fact that a buyer has found out a breach of warranty in diminution or extinction of the worth doesn't prevent him from suing for an equivalent breach of warranty if he has suffered further damage. A breach of warranty doesn't entitle the customer to reject the goods and his only remedy would be those provided in s. 59 namely, to set up against the vendor the breach of warranty in diminution or extinction of the value or to sue the vendor for damages for breach of warranty. From the definition of warranty given in s. 12(3) it's clear that a breach of it gives rise to a claim for damages only on the part of the buyer. it's also laid down by s. 13 that, even within the case of a breach of condition, if the buyer has accepted the goods, or, within the case of entire contracts, a part of them, either voluntarily, or by acting in such how on preclude himself from exercising his right to reject them, he must fall back upon his claim for damages as if the breach of the condition was a breach of warranty.

This section declares the methods by which a buyer who features a claim for damages, in either case, may avail himself of it. It doesn't affect the cases of fraudulent misrepresentation, which can enable the client to line aside the contract nor with cases where by the express terms of the contract the client may return the goods just in case of a breach of warranty. Also, in cases where the client has lawfully rejected the goods, he must proceed not under this section, but under s. 57, and if necessary under s. 61, to recover the acquisition price and interest.

It must be noted here that in such cases, damages are assessed in accordance with the provisions contained in section 73 of Indian Contract Act, 1872. This was also observed by a division bench of the Bombay high court in City And Industrial Development Corporation of Maharashtra ltd., Bombay v Nagpur steel and alloys, Nagpur;

“Remedies under Section 59 aren't absolute and can't be resorted to at any point or strategically point suitable to the customer. He’s duty sure to give notice of his intention. Its proper time, form and manner will, of course, depend on the facts and circumstances of every case. to carry otherwise, would amount to placing the vendor in a clumsy and indefinite position — not warranted either by law or by equity.”

In the case of a guaranty of quality, the presumption is that the measure of damages is that the difference between what the goods are worth at the time of delivery, and what they might are worth consistent with the contract which this must be ascertained by regard to the market value at the time.

In a majority of cases it's found that the warranty in question isn't a warranty as defined in s 12(2), but a condition which falls under s 13(2) to be treated as a warranty. Fairly often it's the condition that the goods should correspond with the outline by which they were sold, or should be fit a specific purpose.

It is necessary that the customer should believe the warranty, and act reasonably, that's to mention, he should take reasonable steps to minimize the damages. Where there's a breach of the warranty that the goods should be fit a specific purpose, the rule again is that the damages should be such, as may naturally be due the breach. This was seen during a case where the plaintiff’s wife died from the consequences of eating tinned salmon which the plaintiff bought from the defendant, the plaintiff was held entitled to recover, as damages for the breach of the warranty, that the salmon would be fit human consumption. Compensation was awarded for medical expenses, funeral costs, and therefore the loss of her life.

There can also be breaches of other conditions which may be treated as breaches of warranty, like the warranty of title. In such a case also, the customer could also be involved in difficulties with sub-buyers, as an example , he may buy a motor car from one who has no right to sell it and should resell it to a 3rd person, from whom truth owner may recover it, or its value.

3. Performance (Section 58)

Subject to the provisions of the precise Relief Act, 1877, in any suit for breach of contract to deliver specific or ascertained goods, the court, may, if it deems fit, on the appliance of the plaintiff, by its decree direct that the contract shall be performed specifically, without giving the defendant the choice of retaining the goods on the payment of damages. The decree could also be unconditional, or upon such terms and conditions on damages, payment of the worth, or otherwise, because the Court may deem just, and therefore the application of the plaintiff could also be made at any time before the decree. The section provides a remedy to the customer and provides no correlative right to the vendor. It's therefore only on application of the customer when suing as plaintiff, that the contract of sale are often enforced specifically and therefore the section only applies when the contract is to deliver specific or ascertained goods. It’s been held that a seller isn't entitled to enforce performance of the contract under s. 58 because it deals with the case of a buyer of specific goods in respect of a contract to deliver specific or ascertained goods. ‘Specific’ here has the meaning which is given in section 2(14) while ‘ascertained’ means ‘identified in accordance with the agreement after a contract of sale is made’. Section 58, as noted above, reproduces with some suitable changes s. 52 of English Act. Before passing of the Sale of goods Act, 1930, there existed Specific Relief Act 1877, Chapter II of which addressed performance of an existing contract. This is often also why Section 58 of the Sale of products Act, 1930 begins with the words “subject to the provisions of Chapter II of the precise Relief Act, 1877”. The court has wide discretion to impose conditions. In one case, performance of agreement to transfer shares was granted subject to a lien to guard the transferor against non-payment of the worth of the shares. In another case, the House of Lords while ordering the precise performance of a contract to sell shares put a condition that the customer should pay interest on the acquisition price which he had been entitled to retain pending the order.

C. Remedies available to both seller and buyer

The suits which will be instituted by either the customer or the vendor are of two types

Suit for repudiation of contract before date or constructive breach

Interest by way of damages and special damages

i. Suit for repudiation of contract before date or constructive breach

Section 60

Where either party to a contract of sale repudiates the contract before the date of delivery, the opposite may either treat the contract as subsisting or wait till the date of delivery, or he may treat the contract as rescinded and use for damages for the breach.

This section, doesn't appear within the English act, and deals with constructive breach of a contract, that's to mention, a manifested intention, by either party, to not be bound by the promise to perform that a part of the contract when the time of performance arrives. Whether or not there has, in fact, been repudiation depends on the facts of every particular case.

The measure of damages isn't fixed by date of the defaulting party’s repudiation. It’s decided, just in case of goods that there's a market, in accordance with the difference between the contract price of the goods and market value thereon day. This is often wiped out order to bring the plaintiff as almost the position as he would are in, had the contract not been repudiated. In cases of contracts where no date is fixed, and a party refuses to perform the contract the principle of reasonable time is applied. During this case the date of repudiation is treated because the date on which the contract is broken and damages are calculated on the idea of this date.

If the party not in default declines to simply accept the opposite party’s repudiation, he keeps the contract alive for all purposes, as are often seen from Frost v Knight. Hence it follows that if, when the time for performance arrives, he himself is unable to perform or doesn't perform his contract, the position are going to be an equivalent because it would are if there had been no anticipatory repudiation by the other party and therefore the latter could also be discharged, and may also sue for damages.

If therefore, the vendor after refusing to simply accept the buyer’s anticipatory repudiation, when the time for performance arrives, tenders goods which aren't of the contract description, or tenders documents under a CIF contract which the customer isn't sure to accept, the customer may lawfully reject the goods or the documents and therefore the seller are going to be without remedy; or the customer may accept the goods tendered and treat the breach of condition as a breach of warranty and recover damages accordingly.

ii. Interest by way of damages and special damages

Section 61

(1) Nothing during this Act shall affect the proper of the vendor or the customer to recover interest or special damages in any case whereby law interest or special damages could also be recoverable or to recover the cash paid where the consideration for the payment of it's failed.

(2) Within the absence of a contract to the contrary, the Court may award interest at such rate a it think fit one the quantity of the price-

(a) To the vendor during a suit by him for the quantity of the worth.- from the date of the tender of the goods or from the date on which the worth was payable.

(b) To the customer during a suit by him for the refund of the worth during a case of a breach of the contract on the part of the seller- from the date on which the payment was made.

This section preserves the proper of a party to a contract of sale to recover special damages, that's to mention , compensation for any loss or damage caused to him by either party’s breach ‘which the parties knew once they made the contract to be likely to result from the breach of it’.

These damages are contrasted with those which ‘naturally arose within the usual course of things’ from the breach. Generally speaking, the latter alone are recoverable by the plaintiff. However, his rule is subject to limitations where the breach has occasioned a special loss, which was actually in contemplation of the parties at the time of getting into the contract, that special loss happening subsequently to the breach must be taken under consideration.

Act 32 of 1839 provided for the payment of interest by way of damages in certain cases. Under the Act, the court could allow interest on debts or certain sums payable by an instrument in writing, from the time when the quantity became payable where a time was fixed for payment, or when no time was fixed, from the date on which the demand was made for payment in writing giving notice to the debtor that interest would be claimed.

It will be observed that the vendor can only recover interest when he's during a position to recover the worth. When he can only sue for damages for breach of contract, he's not entitled to interest under the provisions of this sub-section.

Similarly, the customer can also only recover interest when he's entitled to recover the acquisition price, that's to mention, when he can sue for the worth prepaid as money and received, by reason of total failure, for consideration. He cannot recover interest when his only remedy is to sue for damages, as an example for a breach of warranty, albeit those damages could also be sufficient to extinguish the worth. Moreover, he's only entitled to interest within the case of a breach of contract, presumably by the vendor. This limitation therefore, excludes cases arising under sections 7 and 8 and presumably other cases where the contract depends upon some condition inserted for the advantage of the vendor, and isn't performed due to the non- fulfillment of that condition, or the contract is frustrated by circumstances over which the vendor has no control, in order that in law he wouldn't be susceptible to an action.

D. AUCTION SALE (AS PER SECTION 64)

An auction may be a public sale. The goods are sold to all or any members of the general public at large who are assembled in one place for the auction. Such interested buyers are the bidders. The price they're offering for the goods is that the bid and therefore the goods are going to be sold to the bidder with the very best bid. The person completing the auction is that the auctioneer. He’s the agent of the vendor. So all the principles of the Law of Agency apply to him. But if an auctioneer wishes to sell his own property because the principal he can do so. And he needn't disclose this fact; it's not a requirement under the law.

E. LEGAL PROVISIONS OF AUCTION

As we saw previously, the rules regarding an auction are found within the Sale of goods Act. Section 64 of the Act specifically deals with the rules governing an auction.

1] Goods Sold in Lots

In an auction, there are often many goods up purchasable of the many kinds. If some particular goods are put up purchasable during a lot, then each such lot are going to be considered a separate subject of a separate contract of sale. So each lot ill clear be the topic of its own contract of sale.

2] Completion of Sale

The sale is complete when the auctioneer says it's complete. This will be done by actions also – just like the falling of the hammer, or any such customary action. Till the auctioneer doesn't announce the completion of the sale the potential buyers can keep bidding.

3] Seller may Reserve Right to Bid

The seller may reserve his right to bid. To try to so he must expressly reserve such right to bid. During this case, the vendor on a person on his behalf can bid at the auction.

4] Sale Not Notified

If the vendor has not notified of his right to bid he might not do so under any circumstances. Then neither the vendor nor a person on his behalf can bid at the auction if done then it'll be unlawful.

The auctioneer also cannot accept such bids from the vendor or the other person on his behalf. And any sale that contravenes this rule is to be treated as fraudulent by the customer.

5] Reserve Price

An auction sale could also be subject to a reserve price or an asking price. This suggests the auctioneer won't sell the products for any price below the said reserve price.

6] Pretend Bidding

But if the vendor or the other person appointed by him employs pretend bidding to boost the worth of the goods, the sale is voidable at the choice of the customer meaning the buyer can prefer to honor the contract or he can prefer to void it.

7] No Credit

The auctioneer cannot sell the goods on credit as per his wishes. He cannot accept a bill of exchange either unless the vendor is expressly fine with it.

References-

1. Kappoor, N.D. (2019). Business Law, New Delhi, Sultan Chand & Sons (P) Ltd.

2. Tulsiam, P.C. (2019). Business Law, 4th edition), New Delhi, McGraw Hill Education (MGH).