UNIT 5

PRICING PRACTICES

Pricing strategies

In today’s business world pricing plays an important role for the success of a corporation. While there are various factors that affect a business and pricing of a product is one among them. Determining pricing strategies is extremely important for a business.

Types of pricing strategies

Following are the kinds of pricing strategies

- Cost-plus pricing

It is the only pricing method. The firm calculates the cost of manufacturing the good and adds on a percentage (profit) thereto price to offer the selling price.

- Limit pricing

A limit price may be a price set by a monopolist to discourage economic entry into a market. The limit price is usually less than the average cost of production.

- Price discrimination

price discrimination is setting a different price for same product in different segments to the market. For instance, this will be for various classes of buyers, like ages, or for various Opening times.

- Dynamic pricing

a flexible pricing mechanism made possible by advances in information technology and this strategy is usually employed by internet-based companies.

- Price leadership

in oligopolistic business market usually, the dominant competitor among several leads the way in determining prices, and therefore the others soon follows.

- Target pricing

target pricing may be a pricing method whereby the selling price of a product is calculated to produce a selected rate of return on investment for a specific volume of production.

Companies with high capital investment and public utilities like gas and electrical companies use this strategy.

Marginal cost pricing

this pricing method may be practices of setting the worth/price of products and goods to be equal to the extra cost of manufacturing an additional unit of output.

Cost-plus pricing examples

you make a product for $15 and need a 50% margin of profit so you price it $30

every retailer does this in how to maximise profits

Determination of cost-plus price:

Prof. Andrews in his study, manufacturing business, 1949, explains how a producing firm actually fixes the selling price of its product on the idea of the full-cost or average cost.

The firm finds out the average variable costs (AVC) by dividing the present total costs by current total output. These are the typical variable costs which are assumed to be constant over a wide range of output. In other words, the AVC curve may be a straight line parallel to the output axis over a neighborhood of its length if the costs of direct cost factors are given.

The price which a firm will normally quote for a specific product will equal the estimated average direct costs of production plus a costing-margin or mark-up. The costing-margin will normally tend to cover the prices of the indirect factors of production (inputs) and supply a normal level of net profit, looking the industry asentire.

The formula for costing-margin (or mark-up) is,

m =P – AVC/AVC …(1)

where m is mark-up, p is price and AVC is that the average variable cost and therefore the numerator P-AVC is the margin of profit .

If the price of a book is rs 100 and its price is rs 125,

m = 125 – 100/100 = 0.25 or 25%

if we solve equation (1) for price, the result's

p = AVC (1+m) ….(2)

the firm would set the worth/price ,

p = rs 100 (1 + 0.25) = rs125.

Once this price is chosen by the firm, the costing-margin will remain constant, given its organization, regardless of the level of its output. But it'll tend to vary with any general permanent changes in the prices of the indirect factors of production.

Depending upon the firm’s capacity and given the costs of the direct factors of production (i.e., wages and raw materials), price will tend to stay unchanged, regardless of the level of output. At that price, the firm will have a more or less clearly defined market and can sell the quantity which its customers demand from it.

But how is that the level of output determined? It's determined in any of the three ways:

(a) As a percentage of capacity output; or

(b) because the output sold in the preceding production period; or

(c) because the minimum or average output that the firm expects to sell within the future.

If the firm may be a new one, or if it's an existing firm introducing a new product, then only the 1stand 3rdof those interpretations are going to be relevant. In these circumstances, indeed, it's likely that the 1stwill coincide roughly with the 3rd, for the capacity of the plant will depend upon the expected future sales.

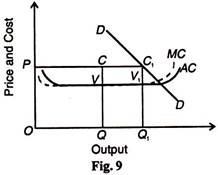

The Andrews version of full-cost pricing is illustrated in figure 9 where AC is that the average variable or direct costs curve which is shown as a horizontal line over a wide/broad range of output. MC is its corresponding marginal cost curve. Suppose the firm chooses OQ level of output.

At this level of output, QC is that the full-cost of the firm made from average direct cost QV plus the costing-margin VC. Its selling price OP will, therefore, equal QC.

The firm will still charge same price OP but it'd sell more depending upon the demand for its product, as represented by the curve dd. During this situation, it'll sell OQ1 output. “This price won't be altered in response to changes in demand, but only in response to changes within the prices of the direct and indirect factors.”

Advantages of cost-plus price:

The main advantages of cost-plus pricing are:

1. When costs are sufficiently stable for long periods, there's price stability which is both cheaper administratively and fewer irritating to retailers and customers.

2. The cost-plus formula is straightforward and easy to calculate.

3. The cost-plus method offers a guarantee against loss-making by a firm. If it finds that costs are rising, it can take appropriate steps by variations in output and price.

4. When the firm is unable to forecast the demand for its product, the cost-plus method are often used.

5. When it's impossible to collect market information for the goods or it's expensive, cost- plus pricing is an appropriate method.

6. Cost-plus pricing is suitable in such cases where the character and extent of competition is unpredictable.

Criticisms of cost-plus price:

The cost-plus pricing theory has been criticized on the subsequent grounds:

1. This method is predicated on costs and ignores the demand of the goods which is a crucial variable in pricing.

2. it’s impossible to accurately ascertain total costs altogether in all cases.

3. This pricing method seems naive because it doesn't explicitly take under consideration the elasticity of demand. In fact, where the worth/price elasticity of demand of a product is low, the cost plus price could also be too low, and the other way around.

4. If fixed costs of firm form large proportions of its total cost, a circular relationship may arise during which the worth/price would rise during a falling market and fall in an expanding market. This happens because average fixed cost per unit of output is low when output is large and when output is low average fixed cost per unit of output is low.

5. Cost-plus pricing method is predicated on data for total cost and not the chance cost that the sale of product incurs.

6. This method can't be used for price determination of perishable goods because it relates to long period.

7. The full-cost pricing theory is criticised for its adherence to a rigid price. Firms often lower the worth/price to clear their stocks during a recession. They also raise the worth/price when costs rise during a boom. Therefore, firms often follow an independent price policy instead of a rigid price policy.

8. Moreover, the term ‘profit margin’ or ‘costing margin’ is vague. The idea doesn't clarify how this costing margin is decided and charged in the full cost by a firm. The firm may charge more or less because the just margin of profit counting on its cost and demand conditions. As Acknowledge by hawkins, “the bulk of the evidence suggests that the dimensions of the ‘plus’ margin varies it grows in boom times and it varies with elasticity of demand and barriers to entry.”

9. Empirical studies in England and therefore the U.SOn the pricing process of industries reveal that the precise methods followed by firms don't adhere strictly to the full-cost principle.\ The calculation of both the average costand therefore the margin may be a much less mechanical process than is typically thought. As a matter of fact, businessmen are reluctant to inform economists how they calculated prices and to debate their relations with rival firms so as to not endanger their long-run profits or to avoid government intervention and maintain good public image.

10. Prof. Earley’s study of the 110 ‘excellently managed companies’ within the U.S doesn’t support the principle of full-cost pricing. Earley found a widespread distrust of full-cost principle among these firms. He reported that the firms followed marginal ACcounting and costing principles, and therefore the majority of them followed pricing, marketing and new product policies.

Full-cost pricing

Full-cost pricing seeks to incorporate every cost of running a business in the cost of manufacturing goods. These costs include rent, a fixed cost or initial outlays of cash for purchasing and renovating a location, which may be a sunk cost. The pricing manager attributes total costs of the business equally to every item produced sellable. Full costs are above marginal costs, because they include quite just the variable costs related to production.

Full-cost issues

full-cost pricing generally fails to realize the theoretically optimal profit-maximizing price. This is often because the manager will include sunk and fixed costs within the decisions about what proportion of every item to supply and what their prices should be. However, those costs, by definition, don't vary with the extent of production, in order that they shouldn't affect production-level decisions. On the opposite hand, full cost is comparatively easy to measure -- simply add up all the prices of the business and divide by the quantity of things the owner or manager wants to sell.

Cost-plus or full-cost pricing:

cost-plus is a short cut method in pricing a product. It means the addition of a particular percentage of the worth/price s as profits to the value of production to reach the price. This is often referred to as а this is precisely cost-plus pricing. This method suggests that the worth/price of a product should cover fixed cost and generate the returns as investments at a fixed mark-up percentage.

Full cost is full monetary value which incorporates average variable costs (AVC) plus average fixed costs (AFC) plus a traditional margin for profit:

P = AVC + AFC + margin of profit or mark-up.

Thus, of the 2 elements of cost-plus price, one is that the cost and therefore the other one is mark-up. These two components are separately analysed.

Cost is a crucial thing in determining price. The cost is that the base on which is grounded by the share of profit. Costs carry main influence on price and are long-term price determinants are different methods of computing the cost.

Broadly speaking, there are three methods of computing the cost:

(i) the actual cost,

(ii) the expected cost, and

(iii) the standard method of costing.

The actual costs are those which are literally incurred on the production of an item. It includes the wage rate, material cost and overhead expenses.

The expected cost is a forecast of the particular expenses for the pricing period. Suppose a product is planned to be introduced in the market, say three months from today, the firm first arrives at the cost of producing one unit at current prices. Then the costs of varied components are projected for subsequent three months to reach the expected cost.

Under the quality method of costing, the capacity of the plant is taken under consideration. For example, the plant could also be present by running at 70 per cent capacity. It's going to be that when it runs at 90 per cent, the cost could also be normal or Optimum. This is often an element which will need to be taken under consideration.

The second aspect is that the percentage mark-up. In determining appropriate mark-up, the firm should carefully evaluate cost, demand elasticity and degree of competition faced by the goods. The firm should also take under consideration the brand image and long run in fixing mark-up. Once the mark-up is fixed, it should be added to the cost of a product.

Cost-plus pricing are often classified into two categories on the idea of mark-up and that they are (i) rigid cost-plus, and (ii) flexible cost-plus.

Rigid cost-plus price:

in rigid cost-plus pricing, it's customary to feature a fixed percentage to the value to urge price. Only variable costs are taken and a fixed mark-up percentage is added thereto. This method is easy to calculate and is according to profit motive.

Flexible cost-plus pricing:

in flexible cost-plus pricing, mark-up isn't rigidly fixed as cost but it's allocated on different heads of variable and fixed costs. It considers all aspects of costs, viz., labour, material, machine hours and all other overheads.

Hall and hitch suggest the subsequent reasons for the firm to watch full cost-pricing:

(i) consideration of fairness,

(ii) ignorance of demand,

(iii) ignorance of potential reaction of competitors,

(iv) the assumption that the short-run elasticity of market demand is low,

(v) the assumption that increased prices would encourage new entrants, and

(vi) administrative difficulties of a more flexible price policy.

Mark-up and switch over:

mark-up may have direct link with turnover. High turnover items may carry low mark-up. This is often thanks to the subsequent reasons:

(i) Customers are conscious of the costs of such items and would shift to other source of supply, and

(ii) for high turnover goods, storing space may be a big problem and cost of space utilization and inventory buildup should be taken under consideration.

Mark-up and rate of return:

there is different way of arriving at the worth/price which is understood because the rate of return pricing. In cost- plus pricing the question of mark-up poses a drag/problem. To bypass this problem, the rate of return pricing method could also be followed. Under this method, the worth/price is decided by the planned rate of return on the investment which is predicted to be converted into a percentage of mark-up.

For fixing rate of return mark-up on cost, three steps are necessary:

(i) To estimate the traditional rate of production and therefore the total cost of a year’s normal production over a cycle,

(ii) To calculate the ratio of invested capital to a year’s standard cost, and

(iii) To switch the capital turn over by rate of return. This provides us on the mark-up percentage.

Determination of cost-plus price:

The determination of cost-plus price is explained below in terms of prof. Andrews’s version. Prof. Andrews in his study, manufacturer, 1949, explains how a producing firm actually fixes the selling priceof its product on the idea of the full-cost or average cost.

The firm finds out the average variable costs(AVC) by dividing the present total costs by current total output. These are the average variable costs which are assumed to be constant over a large range of output. In other words, the AVC curve may be a line parallel to the output axis over a part of its length if the costs of direct cost factors are given.

The price which a firm will normally quote for a specific product will equal the estimated average direct costs of production plus a costing-margin or mark-up. The costing-margin will normally tend to hide the prices of the indirect factors of production (inputs) and supply a traditional level of net profit, looking at the industry as an entire.

The usual formula for costing-margin (or mark-up) is,

M = P-AVC/AVC ….(1)

where m is mark-up, p is price and AVC is that the average variable cost and therefore the numerator P-AVC is that the margin of profit .

If the value of a book is rs 100 and its price is rs 125,

m = 125-100/100 = 0.25 or 25%

if we solve equation (1) for price, the result's

p=AVC (1+m) ….(2)

the firm would set the worth/price ,

p=rs 100 (1+0.25) =rs125.

Once this price is chosen by the firm, the costing-margin will remain constant, given its organization, regardless of the level of its output. But it'll tend to vary with any general permanent changes within the prices of the indirect factors of production.

Depending upon the firm’s capacity and given the costs of the direct factors of production (i.e., wages and raw materials), price will tend to stay unchanged, regardless of the level of output. At that price, the firm will have a more or less clearly defined market and can sell the quantity which its customers demand from it.

But how is that the level of output determined? It's determined in any of the three ways:

(a) as a percentage of capacity output; or

(b) Because the output sold within the preceding production period; or

(c) Because the minimum or average output that the firm expects to sell within the future.

If the firm may be a new one, or if it's an existing firm introducing a replacement/new product, then only the primary and third of those interpretations are going to be relevant. In these circumstances, indeed, it's likely that the primary will coincide roughly with the third, for the capacity of the plant will depend upon the expected future sales.

The Andrews version of full-cost pricing is illustrated in figure 9 where AC is that the average variable or direct costs curve which is shown as a horizontal line over a good range of output. MC is its corresponding marginal cost curve. Suppose the firm chooses OQ level of output.

At this level of output, QC is that the full-cost of the firm made from average direct cost QV plus the costing-margin VC. Its selling price OP will, therefore, equal QC. The firm will still charge an equivalent price OP but it'd sell more depending upon the demand for its product, as represented by the curve dd. During this situation, it'll sell OQ1 output.

“This price won't be altered in response to changes in demand, but only in response to changes within the prices of the direct and indirect factors.”

Advantages:

the main advantages of cost-plus pricing are:

1. When costs are sufficiently stable for long periods, there's price stability which is both cheaper administratively and lesser irritating for retailers and customers.

2. The cost-plus formula is easy to calculate.

3. The cost-plus method offers a guarantee against loss-making by a firm. If it finds that costs are rising, it can take appropriate steps by variations in output and price.

4. When the firm is unable to forecast the demand for its product, the cost-plus method are often used.

5. When it's impossible to collect market information for the goods or it's expensive, cost-plus pricing is an appropriate method.

6. Cost-plus pricing is suitable in such cases where the character and extent of competition is unpredictable.

Criticisms:

The cost-plus pricing theory has been criticised on the subsequent grounds:

1. This method is predicated on costs and ignores the demand of the goods which is a crucial variable in pricing.

2. it’s impossible to accurately ascertain total costs altogether cases.

3. This pricing method seems naive because it doesn't explicitly take under consideration the elasticity of demand. In fact, where the worth/price elasticity of demand of a product is low, the value plus price could also be too low, and the other way around.

4. If fixed costs of a firm form an outsized proportion of its total cost, a circular relationship may arise during which the worth/price would rise during a falling market and fall in an expanding market. This happens because average fixed charge per unit of output is low when output is large and when output is small, average fixed charge per unit of output is low.

5. Cost-plus pricing method is predicated on data for total cost and not the chance cost that the sale of product incurs.

6. This method can't be used for price determination of perishable goods because it relates to long period.

7. The full-cost pricing theory is criticised for its adherence to a rigid price. Finns often lower the worth/price to clear their stocks during a recession. They also raise the worth/price when costs rise during a boom. Therefore, firms often follow an independent price policy instead of a rigid price policy.

8. Moreover, the term ‘profit margin’ or ‘costing margin’ is vague. The idea doesn't clarify how this costing margin is decided and charged within the full cost by a firm. The firm may charge more or less because the just margin of profit counting on its cost and demand conditions. Marginal-cost pricing, in economics, the practice of setting the worth/price of a product to equal the additional cost of manufacturing an additional unit of output in this policy, a producer charges, for every product unit sold, only the addition to total cost resulting from materials and direct labour. Businesses often set prices on the brink of marginal cost during times of poor sales. If, for instance, an item features a marginal cost of $1.00 and a traditional selling priceis $2.00, the firm selling the item might wish to lower the worth/price to $1.10 if demand has waned. The business would choose this approach because the incremental profit of 10 cents from the transaction is best than no sale at least.

in the mid-20th century, proponents of the perfect of perfect competition—a scenario during which firms produce nearly identical products and charge an equivalent price—favoured the efficiency inherent within the concept of marginal-cost pricing. Economists like ronaldcoase, however, upheld the market’s ability to work out prices. They supported the way during which market pricing signals information about the products being sold to buyers and sellers, and that they observed that sellers who were required to cost at marginal cost would risk failing to hide their fixed costs.

Advantages and drawbacks

From the point of economics theory, marginal-cost pricing results in the foremost profitable prices in any sort of market. However, it are often difficult for a business owner within the world to calculate marginal costs, because owners and managers tend to conflate marginal costs with other kinds of costs, like fixed costs and sunk costs. Research from the kellogg school at northwestern university even indicates that some market structures discourage marginal-cost pricing by rewarding price increases that arise when managers take fixed and sunk costs under consideration.

Application of marginal pricing concept

Marginal pricing takes care of the manufacturing costs but not the overhead costs. The low prices attract customers benefitting the business. This high demand would bring profits and better revenues in comparison to products of high price range and relatively low demand. This brings the thought of a short-term revenue boost’ to mind.

Marginal cost pricing may be a concept which requires the presence and use of alternate markets. A supplier or company cannot sell its products at the complete retail price at one section of the market and therefore the marginal rate at another section of a same market.

This is where alternate markets come into play. Careful marketing has got to be performed when the costs are being set for the local market and therefore the import market. The advantage is typically on the exporter’s side because the import market will find it hard to match the import prices and therefore the exporter’s local market prices. Since it also can be disadvantageous for the importing market, the export-import business using marginal pricing should be short term, like non-seasonal sales and perhaps right after the development and found out of a replacement/new plant.

The entirety of this could be strategized and executed carefully. Research and analysis say that a trade-off occurs between the danger and efficient pricing. Marginal cost pricing seems to be Optimal when the utility of the customer doesn't depend upon the worth/price. It says that the tariff’s ‘lump-sum element’ should be greater than that of the fixed charge when the demand is that the same because the fixed cost and with unit elasticity.

Examples of marginal pricing

Let’s check out examples.

• We are mentioning that this idea works only on a short-term basis and marginal pricing works therefore on a time limit. You'll find marginal pricing being employed in year-end sales and seasonal sales where retailers and stores give huge discounts on seasonal clothes or other items that are considered to be outdated. You'll find that woolen clothing is cheaper within the summer than within the winter. So, marginal pricing are often viewed as an idea which will add additional tiny revenue and profits to a corporation.

• locational marginal pricing or simply locational pricing is seen in rural areas especially within the electric service sector due to congestion, diminished service and losses are faced thanks to old generators and power lines that aren't maintained resulting in their low efficiency. Here, customers pay one price in one location and for an equivalent service pay another price in a different location. This is often called locational marginal pricing. One among the costs is that the full retail price and therefore the other is that the cheaper marginal pricing.

• Marginal pricing is also utilized by the travel industry. Airlines, resorts and hotels need a minimum number of seats or rooms filled or the minimum number of individuals checked in to realize a profit. Once they are under booked, they not only not get in revenue but also face losses thanks to maintenance costs and employee salaries that need to be fulfilled however the business is running then. There are websites that have bidding facilities in order that customers can name the worth/price they might wish to pay such underbooked places can get in some revenue.

• Some companies make the costs such they're lower for products in lower demand and better for those in higher demand. This is often discrimination in price.

Advantages of marginal pricing

as we've already seen, marginal pricing is most optimal for short-term solutions and this makes sure that one needn't worry about the consequences it'll wear fixed costs of maintenance and overhead. It majorly focuses only on what has got to be done to realize profits and to equalize the quantity of labour or investment.

Disadvantages of marginal pricing

Marginal pricing always reminds you that there's always the danger that you simply might not recover the entire fixed charge price and it'll also get difficult to increase the price as customers get used to the lower price and should not continue with the goods once prices increase.

Accessory sales

Advantage:

several products have Accessory items. Marginal pricing gives thanks to accessory sales which is extremely profitable for a service provider or retailer. It can make these pricing strategies very viable and also boost the margins. The cellphones are often considered as an example. The service is often considered the main accessory and other Accessories are often the cellphone charger, earphones, telephone charger and therefore the usb cord.

The telephone itself can then be sold at a lower cost because the summation of the whole cost containing the costs of the entireaccessory are going to be profitable within the long run as this offer will appeal to the audience. This may reap them high profits within the future with their products in large demand.

Disadvantage:

all of this does sound promising, but even this has its minus point. The minus point contradicting the advantage is marginal cost pricing for products that don't have accessory items. The above point would definitely not apply then.

Customers who are price-sensitive

Advantage:

lower prices usually cause higher demand and incremental profits. Lower prices also can show a level of increase within the number of units sold. It's said to be a new way to be used while entering the market promoting a new product.

Disadvantage:

customers are often price-sensitive (most are, nowadays) and can mostly not subscribe or buy the goods anymore if prices are increased to compensate the rising fixed charge of production.

Market prices

Advantage:

it is advantageous for short-term benefits. It makes the brand high-quality and high-service when the strategy for pricing is that the promotional and short term. It also can help faster entry into the market. But it'll cause the gain of several customers who are price sensitive.

Disadvantage:

marginal cost pricing doesn’t consider the market prices. The market rates aren't included when the costs are being quoted.

Another perspective of marginal pricing that has been mentioned is of the govt. of the importing country. It's said that this idea of marginal cost pricing could also be viewed as dumping. Dumping is that the marketing or selling of a product at a lower cost within the foreign or importing market when it's being sold at the domestic marketplace for a higher price. The foreign market tends to feel threatened on behalf of their competing industries from unfair competition and seek protection. The exporting companies can faces imposition by the importing government. It are often of high countervailing dues to correct the worth/price imbalance.

Another flaw is that the exporting company might shift its focus to the local market as soon as there seems to be a rise in sales within the domestic market itself. This will cause tiffs and mistrust among countries and foreign buyers where their trust will sway even when it involves other suppliers in the same market. This way, even a small careless mistake can cost a neighborhood of the nation’s economy.

Hence, companies employ this strategy once they realize they will earn additional revenue by selling excess unsold products. It's to not be included during a long-term plan because it would definitely bring losses to the corporate by the minimal revenue. Marginal cost pricing is unquestionably Opening new doors for combatting periodical revenue issues and for soaring sales.

3.4 MARKUP PRICING TECHNOLOGY

Markup pricing is that the most commonly employed pricing method. Given the recognition of the technique, it behooves managers to completely understand the rationale for markup pricing. When this rationale is known, markup pricing methods are often seen because the practical means for Achieving Optimal prices under a good sort of demand and price conditions.

Markup pricing technology

the development of pricing practices to profitably segment markets has reached fine art with the internet and use of high-speed technology. Why do business week, Forbes, fortune, and therefore the wall street journal offer bargain rates to students but to not business executives? It's surely not because it costs less to deliver the journal to students, and it's not out of benevolence;

It is because students aren't willing or ready to pay the quality rate. Even at 50 percent off regular prices, student bargain rates quite cover marginal costs and make a big profit contribution. Similarly, senior citizens who erode holiday inns enjoy a ten to fifteen percent discount and make a meaningful contribution to profits. Conversely, relatively high prices for popcorn at movie theaters, peanuts at the Ball Park, and clothing at the peak of the season reflect the very fact that customers are often insensitive to cost changes at different places and at different times of the year. Regular prices, discounts, rebates, and coupon promotions are all pricing mechanisms wont to probe the breadth and depth of customer demand and to maximise profitability.

Although profit maximization requires that prices be set in order that marginal revenues equal marginal cost, it's not necessary to calculate both to line optimal prices. Just using information on marginal costs and therefore the point price elasticity of demand, the calculation of profit-maximizing prices is quick and simple. Many firms derive an optimal pricing policy using prices set to hide direct costs plus a percentage markup for profit contribution. Flexible markup pricing practices that reflect differences in marginal costs and demand elasticity constitute an efficient method for ensuring that MR = MC for every line of products sold. Similarly, peak and off-peak pricing,

price discrimination, and joint product pricing practices are efficient means for Operating in order that MR = MC for every customer or customer group and goods class.

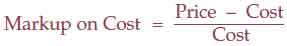

Markup on cost

In a conventional approach, firms estimate the average variable costs of manufacturing and marketing a given product, add a charge for variable overhead, then add a percentage markup, or margin of profit. Variable overhead costs are usually allocated among all products consistent with average variable costs.

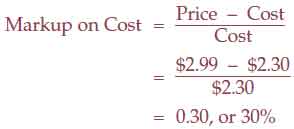

For instance, if total variable overhead costs are projected at $1.3 million per annum and variable costs for planned production total $1 million, then variable overhead is allocated to individual products at the speed of 130 percent of variable cost. If the typical variable cost of a product is estimated to be $1, the firm adds a charge of 130 percent of variable costs, or $1.30, for variable overhead, obtaining a totally allocated cost of $2.30. To the present figure the firm might add a 30 percent markup for profits, or 69¢, to get a price of $2.99 per unit.

Markup on cost for a private product or line expressed as a percentage of cost. The markup-on-cost, or cost-plus, formula is given by the expression:

The numerator of this expression, called the margin of profit, is measured by the difference between cost and price. Within the example cited previously, the 30 percent markup on cost is calculated as

solving equation 12.1 for price provides the expression that determines price during a cost-plus pricing system:

price = cost (1 + markup on cost)

continuing with the previous example, the goods selling priceis found as

price = cost (1 + markup on cost)

= $2.30(1.30)

= $2.99

Markup on price

Profit margins, or markups, are sometimes calculated as a percentage of price rather than cost.

Markup on price is that the margin of profit for a private product or line expressed as a percentage of price, instead of cost as within the markup-on-cost formula. This alternative means of expressing profit margins are often illustrated by the markup-on-price formula:

Markup on price = price – cost/price

Profit margin is that the numerator of the markup-on-price formula, as within the markup-on-cost formula. However, cost has been replaced by price within the denominator. The markup-on-cost and markup-on-price formulas are simply alternative means for expressing the relative size of profit margins. To convert from one markup formula to the Opposite, just use the subsequent expressions:

Markup on cost = markup on price/1 – markup on price

markup on price = markup on cost/1 + markup on cost

therefore, the 30 percent markup on cost described within the previous example is like a 23 percent markup on price:

Markup on price = 0.3 /1 + 0.3 = 0.23 or 23%

An item with a price of $2.30, a 69¢ markup, and a price of $2.99 features a 30 percent markup on cost and a 23 percent markup on price. This illustrates the importance of being consistent within the choice of a price or price basis when comparing markups among products or sellers. Markup pricing is usually criticized as a naive pricing method based solely on cost considerations— and therefore the wrong costs at that. Some who employ the technique may ignore demand conditions, emphasize fully allocated Accounting costs instead of marginal costs, and reach suboptimal price decisions. However, a categorical rejection of such a well-liked and successful pricing practice is clearly wrong. Although inappropriate use of markup pricing formulas will cause suboptimal managerial decisions, successful firms typically employ the tactic in a way that's consistent with profit maximization.

Markup pricing are often viewed as an efficient rule of- thumb approach to setting optimal prices.

Role of cost in markup pricing

Although a various cost concepts are employed in markup pricing, most firms use a standard, or fully allocated, cost concept. Fully allocated costs are determined by first estimating direct costs per unit, then allocating the firm’s expected indirect expenses, or overhead, assuming a typical or normal output level. Price is then based on standard costs per unit, regardless of short-term variations in Actual unit costs.

Unfortunately, use of the quality cost concept can create several problems. Sometimes, firms fail to regulate historical costs to reflect recent or expected price changes. Also, accounting costs might not reflect true economic costs. For instance, fully allocated costs are often appropriate when a firm is working at full capacity. During peak periods, when facilities are fully utilized, expansion is required to extend production. Under such conditions, a rise in production requires a rise altogether plant, equipment, labor, materials, and other expenditures. However, if a firm has excess capacity, as during off-peak periods, only those costs that really rise with production—the incremental costs per unit—should form a basis for setting prices.

Successful firms that employ markup pricing use fully allocated costs under normal conditions but selling price discounts or Accept lower margins during off-peak periods when excess capacity is out there. In some instances, output produced during off-peak periods is far cheaper than output produced during peak periods. When fixed costs represent a considerable share of total production costs, discounts of 30 percent to 50 percent for output produced during off-peak periods can often be justified on the idea of lower costs.

“Early bird” or afternoon matinee discounts at movie theaters provide a stimulating example. Apart from cleaning expenses, which vary consistent with the amount of consumers, most movies expenses are fixed. As a result, the revenue generated by adding customers during off-peak periods can significantly increase the theater’s profit contribution. When off-peak customers buy regularly priced candy, popcorn, and soda, even lower afternoon ticket prices are often justified. Conversely, on Friday and Saturday nights when movie theaters Operates at peak capacity, little increase within the number of consumers would require a costly expansion of facilities. Ticket prices during these peak periods reflect fully allocated costs. Similarly, MCdonald’s, burger king, arby’s, and other fast-food outlets have increased their profitability substantially by introducing breakfast menus. If fixed restaurant expenses are covered by lunch and dinner business, even promotionally priced breakfast items can make a notable contribution to profits.

Role of demand in markup pricing

Successful companies differentiate markups consistent with variations in product demand elasticity. Foreign and domestic automobile companies regularly offer rebates or special equipment packages for slow-selling models. Similarly, airlines promote different pricing schedules for business and vacation travelers. The airline and automobile industries are only two samples of sectors during which vigorous competition requires a careful reflection of demand and provide factors in pricing practices. Within the production and distribution of the many goods and services, successful firms quickly adjust prices to different market conditions.

Examining the margins set by a successful regional grocery chain provides interesting evidence that demand conditions play a crucial role in cost-plus pricing. Table shows the firm’s typical markup on cost and markup on price for a spread of products. Afield manager with over 20 years’ experience within the grocery business provided the author with useful insight into the firm’s pricing practices. He stated that the “price sensitivity” of an item is that the primary consideration in setting margins. Staple products like bread, coffee, hamburger, milk, and soup are highly price sensitive and carry relatively low margins. Products with high margins tend to be less price sensitive.

Note the wide selection of margins applied to different items. The 0 percent to 10 percent markup on cost for hamburger, for instance, is substantially less than the 15 percent to 35 percent margin on steak. Hamburger may be a relatively low-priced meat with wide appeal to families, college students, and low-income groups whose price sensitivity is high. In contrast, relatively expensive sirloin, t-bone, and porterhouse steaks appeal to higher-income groups with lower cost sensitivity.

It is also interesting to ascertain how seasonal factors affect the demand for grocery items like fruits and vegetables. When a fruit or vegetable is in season, spoilage and transportation costs are at their lowest levels, and high product quality translates into enthusiastic consumer demand, which results in high margins. Consumer demand shifts faraway from high-cost/low-quality fresh fruits and vegetables once they are out of season, thereby reducing margins on these things.

In addition to seasonal factors that affect margins over the course of a year, some economic process affect margins within a given product class. In breakfast cereals, for instance, the markup on cost for highly popular corn flakes averages only 5 percent to six percent, with brands offered

Price discrimination is when a seller sells a selected commodity or service to different buyers at different prices for reasons not concerning differences in costs.

Before we start, let’s check out some examples:

• a local physician charges more to rich patients as compared to poor patients for an equivalent service.

• Electricity companies sell electricity at a less expensive rate in rural areas as compared to urban areas.

These are samples of price discrimination. In a monopoly, the vendor adopts this method of pricing to earn abnormal profits. It's important to recollect that price discrimination cannot persist under perfect competition since the vendor has no control over the market value of the product/service. It requires a component of monopoly to permit him to influence the worth/price.

Conditions for price discrimination

Price discrimination is feasible under the subsequent conditions:

1. The vendor must have some control over the availability of his product. Such monopoly power is important to discriminate the worth/price.

2. The vendor should be ready to divide the market into a minimum of two sub-markets (or more).

3. The price-elasticity of the goods must vary in several markets. Therefore, the monopolist can set a high price for those buyers whose price-elasticity of demand for the goods is a smaller amount than 1. In simple words, even if the vendor increases the worth/price, such buyers don't reduce the Acquisition volume.

4. Buyers from the low-priced market shouldn't be able to sell the goods to buyers from the high-priced market.

A monopolist, in such a case, transfers some amount of product from market a to market b. This is often because, in market b, the high elasticity of demand implies larger marginal revenue. It's important to notice here that when units are transferred from A to B, price during A will rise and fall in B.

However, there's a limit to which the monopolist can transfer between markets a and b. Once he reaches that limit and reaches some extent where the MRs in both the markets become equal thanks to the transfer of output, transferring more will not be profitable. At this stage, the monopolist starts charging different prices within the two markets. So, he charges a better price within the market with a lower elasticity of demand and a lower cost within the market with a better elasticity of demand.

Generally, organizations produce more than one product in their line of production. Even one product of a corporation can differ in styles and sizes. For instance, a refrigerator manufacturing organization produces refrigerators in several colors, sizes, and features. Similarly, an automobile organization manufactures vehicles in several colors, sizes, and mileage. The pricing just in case of multiple products is named multiple product pricing.

The demand curve for multiple products would be different. However, the MC curve of those products is same as these are produced under interchangeable production facilities. Therefore, AR and MR curves are different for every product. On the Opposite hand, AC and MC are inseparable. Therefore, the condition of MR=MC can't be applied on to fix the costs of every product.

The solution of this problem was provided by e.w. Clemens who stated how the multi-product organizations fix prices of their products. Suppose there are four differentiated products. A, b, c, and d produced by a corporation.

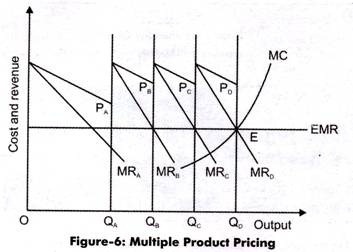

Figure-6 shows multiple product pricing:

as shown in figure-6, the AR(price) and MR curves for four products are shown as four different curves and MC curve is shown because the total of MC of all the products. Suppose the mixture MR curve, which is that the total of all individual MR curves passes through point e on the MC curve.

From point e, a parallel line, equal marginal revenue (EMR) is drawn towards y- axis (parallel to x-axis). This parallel line passes through the m rs of a, b, c, and d. The output and costs of those four products are determined at the points where their respective MC and MR curves intersect one another.

As shown in figure-6, OQa, Qaqb, QbQC, QCQd are the output levels of products a, b, c, and d and PaQa, PbQb, PcQC, PdQd are the costs of the products respectively. These are the utmost price and output levels of a corporation.

Multiple products:

The traditional theory of price determination is based on the idea that the firm produces one homogeneous product. But firms usually produce more than one product. When firms produce several products, managers must consider the interrelationships between those products.

Such products could also be joint products or multi-products. Joint products are those where inputs are common in productive process. Multi-products are creation of the product line Activity with independent inputs but common overhead expenses. Pricing of multi-product or joint product requires little extra caution and care.

For evolving price policy for multi-product firm, certain basic considerations involved in deciding are:

(i) price and price relationship in line ,

(ii) demand relationship in line , and

(iii) competitive differences.

They are explained as follows:

(i) price and price relationship:

For evolving a price policy for any product, price and price relationship is that the basic consideration. Cost conditions determine price. Therefore, cost estimates should be correctly made. Although a firm must recover its common costs, it's not necessary that prices of every product be high enough to hide an arbitrarily apportioned share of common costs.

Proper pricing does require, however, that prices a minimum of cover the marginal cost of manufacturing each good. Incremental costs are additional costs that might not be incurred if the goods weren't produced. As long because the price of a product exceeds its incremental costs, the firm can increase total profit by supplying that product.

Hence decisions should be based an evaluation of incremental costs. A price that gives maximum contribution over costs is usually acceptable but in multi-product cases, incremental cost becomes more essential to form such decisions.

A set of other price policies should be considered and that they are:

(i) prices of multi-products could also be proportional to full cost. This price may produce equal percentage of margin of profit for all products. If the complete cost for all products are assumed equal then the pricing are going to be equal.

(ii) Pricing for multi-products could also be proportional to incremental cost.

(iii) Prices of multi-products could also be assessed with regard to their contribution margin as proportional to conversion cost.

(iv) Prices of multi-product could also be fixed differently keeping into consideration market segments.

(v) Prices for multi-products could also be fixed as per the goods life cycle of every product.

(ii) Inter-relation of demand for multi-product:

Demand inter-relationships arise due to competition during which case they become substitutes or they'll be complementary goods. Sale of 1 product may affect the sale of another product. Different demand elasticity of various consumers may allow the firm to follow policies of price discrimination in several market segments. Two products of an equivalent price could also be substitutes to every other with cross elasticity of demand thanks to high degree of competitiveness.

In such a situation, pricing of the multi-products will need to be wiped out such an extended way that maximum return might be obtained from each market segments by selling maximum products. Demand inter-relationships within the case of multiple products make it clear that we should always take under consideration a radical analysis of the entire effect of the choice on the firm s revenues.

(iii) Competitive differences:

yet another important point should be considered for creating price decisions, for a line is that the assessment of degree of competitiveness. Such an assessment will found out market share for every product. A product having large market share can stand a high makeup and may contribute in touch the losses.

there is competition among a couple of sellers of a comparatively homogeneous product that has enough cross elasticity of demand in order that each seller must in his pricing decisions appreciate of rivals’ reaction. Each producer is really conscious of the disastrous effects that an announced reduction of his own price would wear the costs charged by competitors. The firm should also analyse whether the competitors have free entry to the market or not.

Marginal technique for pricing multi-products:

Marginal technique for pricing multi-products is predicated on the logic that when the firm has spare capacity, unutilized technical resources, managerial and organizational abilities and capabilities, the firm enters into production of varied other products with most profitable uses of alternatives.

The product is technically independent within the production process. For choosing these alternatives, the firm considers marginal costs of every such alternative and adopts those which supply higher margin on cost through sales.

Since each additional unit produced entails a further cost also as generates additional revenue, the logic of profit maximization stresses that production should be stabilized at some extent where MR just covers MC. ‘marginal cost more accurately reflects those changes in costs which result from a choice. Marginal pricing is more useful due to the prevalence of multi-product firms.

A firm shall produce the multi-product to the extent where MR from sales of these products equals the MC. If MC is quite MR then the firm shall stop producing and selling one among the products which supply less MR than MC.

Pricing of multiple products or joint products:

Products are often related in production also as demand. One sort of production interdependency exists when goods are jointly produced in fixed proportions. The method of manufacturing mutton and hides during a slaughter home is angood example of fixed proportion in production. Each carcass provides a particular amount of mutton and hide.

There is little that the slaughter house can do to change the proportion of the 2 products. When goods are produced in fixed proportion they ought to be thought of as a ‘product package’. Because there's no thanks to produce one a part of this package without also producing the Opposite part, there's no conceptual basis for allocating total production costs between the 2 goods.

Pricing of joint products are often explained under two different circumstances:

(i) When there's fixed proportion of products.

(ii) When there's variable proportion of products.

(i) Joint products with fixed proportion:

In joint product case with fixed proportion of quantity, there's no possibility of increasing one at the expense of another. In this situation, the costs are joint and can't be increased at the expense of another. During this situation, the costs are joint and cannot be allocated to every product on any sound basis. Although the 2 goods are produced together, their demands are independent.

However, there's one marginal cost curve for both products. This reflects the fixed proportion of production, i.e., the marginal cost is that the cost of supplying another unit of the goods package. Where goods are jointly produced as within the case of mutton and hides, pricing decision should take this interdependency under consideration.

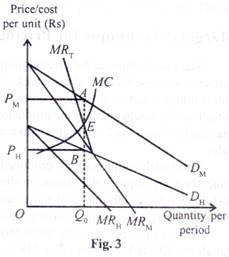

Figure 3 indicates how profit maximising prices and quantities are determined. PM and PH represent the foremost profitable prices for the joint products. The figure carries the idea that every product is produced in fixed proportion because the output point for both is one and therefore the same whereas their demand and marginal revenue curves are separate for various markets existing for them. MRm and MRh are the marginal revenue curves for mutton and hides respectively. But when a further animal is processed at a slaughter house both mutton and conceal become available for sale . Hence the marginal revenue related to sale of a unit of the goods package is that the sum of the marginal revenues.

This sum is represented by the line MRt. MRt is decided by adding MRm and MRt, for every rate of output. Graphically, it's the vertical sum of the marginal revenue curves of the 2 products. The profit maximising output QO is determined by the intersection of MRt and MC curve at point e with price of mutton OPm and of hides OPh.

(ii) joint products with variable proportions: pricing of joint products which may be produced with variable proportions presents interesting analysis of price cost and output when it's possible for a firm to supply joint products in several proportions the entire cost has got to be divided among different products because there can't be a being e marginal cost curve figure 4 illustrates the pricing method of multiple products with variable proportions wherein three main things are to be observed:

(i) The production possibility curve is concave to the origin indicating imperfect adaptability of productive resources in producing products a and b in other words it indicates the number of a and в which may be produced with an same total cost it's the iso-cost curve labelled as TC within the figure

(ii) The iso-revenue lines define the costs which the firm receives for the 2 products irrespective of any combination of their output they're shown as TR within the figure

(iii) the simplest combinations are the points of tangency of iso-cost curves and iso-revenue lines tor Optimum production and maximisation of sales revenues or profits thus the Optimal output combination is at some extent where an iso-revenue line is tangent to an iso-cost curve we will find the optimal combination by comparing the profit level at each tangency point and selecting the purpose with the very best profit level given fixed product prices

Suppose a firm produces and sells two products a and b given their prices each iso-cost curve shows the quantities of those products which will be produced at an equivalent cost each iso-revenue line shows the combinations of outputs of a and в that yield an equivalent revenue

The problem facing the firm is to determine the outputs of joint products a and b to start with an output combination where an iso-revenue line isn't tangent to the iso-cost curve allow us to take such some extent as p within the figure this can't be the Optimal output combination

Because it's possible to extend revenue without changing cost by moving to point r on an equivalent iso-cost curve where the iso-revenue line is tangent to the iso-cost curve the firm has got to take into consideration the profit maximization Optimal output of combination a and в products it compares the extent of profit at each tangency point and chooses that time where the profit level is that the highest within the figure there are four tangency points k s and t like the

Profit levels = rs 2 crore = rs 6 crore and = rs 4 crore respectively

It is clear from the above that the firm will choose the Optimal output combination at point s where it produces and sells oa3 units of product a and ob3units of product в and earns the very best profit rs it cannot produce at the upper output combination point t as compared to s because its profit level will fall to rs 4 crore

Transfer pricing is one among the foremost complex problems in pricing the expansion of large scale multi- divisional organisations has given rise to the matter of pricing commodities that are transferred internally from one division to a different the divisional organisations are preferred thanks to the subsequent reasons:

(i) It provides a scientific way of delegation and deciding

(ii) For correct evaluation of contribution

(iii) For the precise evaluation of manager’s performance

This involves the matter of sub-Optimization

The transfer price must satisfy the subsequent two criteria:

(i) It should help establish the profitability of every division or department

(ii) It should permit and encourage maximisation of the profits of the corporate.

For determining the transfer price there are three alternative methods they're explained as follows:

(i) market price basis: the suitable system of transfer of products from one division to a different under same management to a different company is that the market price basis the market price should be the transfer price wherever a market value exists for a product the inter-divisional transfer price should equal the market value to avoid sub-Optimization this method definitely avoids the likelihood of passing the inefficiencies of 1 department to the Other departments

(ii) cost basis: in case the goods produced by a division of the firm are often sold only to a different division of the firm the inter-divisional transfer should be priced at the extent of the particular cost of production here transfer prices are going to be useful to realize the simplest joint level of output it'll maximise profits

(iii) cost plus basis: under this method the products and services of every department are charged on the idea of actual cost plus a margin by way of profit the main defect of this method is that the transferring department may add a high margin soon raise the profit of the department it's going to end in setting the ultimate price unduly high thereby affecting sales

Transfer price determination:

Objectives:

Firms have the subsequent objectives while determining the transfer price:

- The aim of the firm is to make sure that its goal coincides thereupon of the related divisions

- The price of the transferred product should be so determined that the profitability of every division might be ensured

- The worth/price should be such it could induce profit-maximisation of the company as whole instead of a specific division

Large firms often divide their Operations into various divisions or department’s one division uses the goods of the other division

In such a situation firms faceproblem in determining an appropriate price for the goods transferred from one division or sub-division to the other, in other words transfer pricing refers to the worth/price determination of products and services transferred among interdependent units or divisions within the organisation this Operate as a measure of the economic Achievement of profit making divisions within the organisation it's necessary to think about various situations while determining

Transfer price transfer pricing: absence of an external market:

If an intermediate product has no external market transfer pricing are according to the marginal cost of the producer suppose that a firm has two independent divisions: production division and marketing division.

The production division produces one product that's sold to the marketing division of an equivalent firm.

The price at which it sells is named transfer price. Further, the marketing division presents that product as a final product by packaging it and sells it to the general public. We also assume that the goods manufactured by the production division has no market outside the firm.

In other words, the marketing division completely depends upon the assembly division for the availability of the goods and therefore the production division depends on the marketing division for its demand. Therefore, the entire quantity of the goods manufactured by the production division must be equal to the quantity sold by the marketing division.

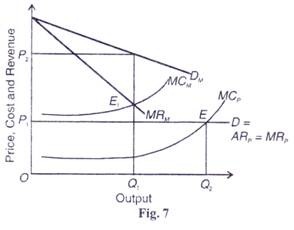

In fig. 6 MCp and MCm are the value curves of production division and marketing division respectively and MC is that the firm’s cost curve. This curve is that the summation of MCp and MCm curve Df is that the firm’s demand curve and MR is that the marginal revenue curve for the ultimate product. The firm is going to be in equilibrium at point e where its MC curve cuts its MR curve. The firm is going to be selling OQ quantity of the goods at OP price.

Now, the question is how much price the production division should charge for its product from the marketing division? The transfer price is equal to the marginal revenue of the assembly division. The transfer price once determined is usually stable because the demand curve of production division is horizontal on which the marginal revenue of production division is equal to the transfer price, i.e., D=MRp—P1. The assembly division will earn the utmost profit for its intermediate product at that time where price (p1) which is additionally its marginal revenue (MRp), is equal to its marginal cost (MCp), i e P1= MRp =MCp. This example is at point where the MCp curve cuts the. D=MRp=P1 curve from below.

2. Transfer pricing: presence of an external market:

If there's an external marketplace for the intermediate product, the production division may produce more product than the marketing division needs and should sell the excess product within the external mare. On the opposite hand, it's going to produce but the requirements of the marketing division and therefore the market division can obtain the remainder of its requirements from the external market. Thus, it's freer for maximizing its profit.

(1) transfer pricing: In a perfectly competitive external market:

in the case of a wonderfully competitive external market, where the intermediate product are often sold or bought from the superbly competitive outside market by the firm, the quantity produced by the assembly division might not be equal to the specified quantity for the marketing division.

In such a situation transfer price of intermediate product is that the market value of that product. The firm are often within the maximum profit situation only all its divisions Operate at their related MR — MC points. In these conditions, we explain transfer pricing in terms of figure 7.

In the figure, d is that the demand curve of intermediate product which may be a horizontal line. This curve shows marginal revenue (MRp), average revenue (arp) and price (p) of the production division. Consistent with the figure,

The production division will receive the maximum profit at OQ2 output level because at this level marginal cost of production (MCp) is equal to its marginal revenue (MRp) which determines OP1 price. Here the equilibrium is at point e where the MCp curve cuts die D=ARp = MRp curve from below.

To maximize total profit of the firm within the perfectly competitive market, it'll be appropriate to keep transfer price at OP1 level. It's at this price that the production division will sell its intermediate product to the marketing division or to outside customers, and therefore the marketing division also will give only OP1 price for the intermediate product to the assembly division.

The marginal cost curve of the marketing division is MCm which is that the summation of marginal cost and transfer price p1. To maximise its profit, marketing division will need to purchase OQ1 quantity where its marginal cost MCm is equal to its marginal revenue MRm at point within the figure, the maximum profitable quantity for the assembly division are going to be OQ2 which for the’ marketing division OQ1 hence, the assembly division will sell OQ2 – OQ1 = q2q1 portion of its output in the external market.

Transfer pricing:

In imperfectly competitive external market, here we discuss transfer pricing in that market situation where the production division sells its product in imperfectly competitive external market also on the marketing division. In such a situation, a crucial problem of price differentiation arises in different markets.

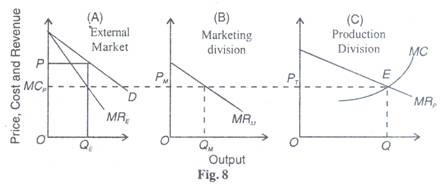

The production division will get the maximum profit, when the marginal revenue in each market is equal to marginal revenue for the total market, and total market marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost. In other words, transfer price for the marketing division should be equal to the marginal cost of production division. Transfer price determination in the case of imperfectly competitive external market is shown is fig. 8.

Panel (A) of the figure is said to an imperfectly competitive external market during which D is its demand curve and MRe is its marginal revenue curve. Panel (b) is said to the marketing division in which MRm is that the net marginal revenue curve of the marketing division. In other words, MRm = (Pt =MCp). Here, transfer price (Pt) is equal to the marginal cost of the assembly division (MCp) panel (c) is related to the production division.

Its marginal revenue curve MRp is that the summation of marginal revenue of the marketing division in the firm (MRm) and marginal revenue of the external market (MRe). The Optimum production level of the production division is OQ when MRp curve is equal to MC curve at point E and therefore the transfer price is OPt. The marketing division wall buy OQm quantity of output at OPt transfer price from the assembly division and therefore the production division can sell OQe units of its production at OP price in the external market.