UNIT 5

Behavioral Foundations

When a person buys shares, bonds or debentures of a public limited company from the market, it is generally said that he has made investment. But this is not the real investment which determines income and employment in the country and with which we are here concerned. Buying of existing shares and bonds by an individual is merely a financial investment.

When one individual purchases the shares or bonds, some other one would sell them. Thus, the purchase and sale of the shares merely represents the change in the ownership of assets which already exists rather the creation of new capital assets. It is the new addition to the stock of physical capital such as plant, machines, trucks, new factories and so on that creates income and employment. Therefore, by real investment we mean the addition to the stock of physical capital.

Thus, in economics, investment means the new expenditure incurred on addition of capital goods such as machines, buildings, equipment, tools, etc. The addition to the stock of physical capital i.e., net investment raises the level of aggregate demand which brings about addition to the level of income and employment in the economy. Keynes and many other economists also include the increase in the inventories of consumer goods in the capital of the country and therefore in the investment.

Business Fixed Investment:

Business fixed investment means investment in the machines, tools and equipment that businessmen buy for use in further production of goods and services.

The stock of these machines or plant equipment etc. represents fixed capital.

The term ‘fixed’ in it implies that expenditure made on the machines, equipment etc. continues to be used for production for a relatively long time. This is in contrast to inventory investment whose components will be either used shortly for production or sold shortly to others for further production.

Business fixed investment is important in two respects. First, business fixed investment is an important component of aggregate demand and therefore plays a significant role in the determination of natural income and employment. Business fixed investment is a volatile component of aggregate demand and, as Keynes emphasized, fluctuation in levels of fixed business investment is responsible for business cycles in a free market economy.

Keynes put forward a theory of investment which states that business fixed investment is determined by expected rate of profit (which he calls marginal efficiency of capital) and rate of interest. Since rate of interest in the short run is relatively sticky, it is changes in expectations about earning profits in future that cause fluctuations in business fixed investment.

According to the neoclassical theory, business fixed investment is determined by the marginal product of capital on one hand and user’s cost of capital on the other. The user’s cost of capital merely depends on the price of capital goods, the interest rate and the depreciation rate. According to the neoclassical model, if marginal product of capital exceeds user’s cost of capital, firms will find it profitable to undertake fixed investment.

In this model, rate of interest, which is an important component of the user cost of capital, and taxation of profits play an important role in the determination of business fixed investment.

Residential Investment:

Residential investment refers to the expenditure which people make on constructing or buying new houses or dwelling apartments for the purpose of living or renting out to others. Residential investment varies from 3 per cent to 5 per cent of GDP in various countries.

Two important features of residential investment are worth noting. First, since the average life of a housing unit is of 40 to 50 years, the stock of existing housing units at a point of time is very large as compared to the new residential investment in a year (i.e., flow of residential investment). Second, there is well developed resale market for housing units so that people who construct or own them can sell them in this secondary market.

Residential investment depends on price of existing housing units. The higher the price of existing units, the higher will be investment in constructing and buying new housing units. The price of housing units is determined by demand for housing units which slopes downward and the supply of existing units which is a fixed quantity and its supply curve is therefore vertical straight line.

In the long run demand for housing is determined by rate of population growth and formation of new households. The higher rate of population growth will lead to the increase in demand for housing units. The tendency towards two-member households has led to greater demand for housing units.

Income is another important factor determining demand for houses and therefore greater residential investment. Since level of income over time fluctuates a good deal, there is strong cyclical pattern of investment in residential construction.

Finally, interest is another important factor that determines demand for dwelling units. Most houses, especially in cities, are purchased by borrowing funds from banks for a long time, say 20 to 25 years. Generally, the houses purchased are mortgaged with banks or other financial institutions who provide funds for this purpose.

The individuals who purchase houses on mortgage borrowing pay monthly installment of original sum borrowed plus interest. Therefore demand for housing units is highly sensitive to changes in rate of interest. Therefore, monetary policy has a substantial effect on residential investment.

Inventory Investment:

Firms hold inventories of raw materials, semi-finished goods to be processed into final goods. The firms also hold inventories of finished goods to be sold shortly. The change in the inventories or stocks of these goods with the firms is called inventory investment. Now, why do firms hold inventories? The first motive of holding inventories is smoothing of the level of production.

The firms experience temporary booms and busts in sales of their output. Instead of adjusting their production each time to match the changes in sales of the product they find cheaper to produce goods at a steady rate. With this steady rate of production when sales are low, the firms will be producing more than they are selling and therefore in these periods they will hold the extra goods produced as inventories.

On the other hand, when sales are high with a steady rate of production, they will be producing less than they sell. In such periods to meet the market demand for goods, they will take out goods from inventories to meet the demand.

The second reason for holding inventories is that it is less costly for a firm to buy inputs such as raw materials less frequently in large quantities to produce goods and therefore it is required to hold inventories of raw materials and other intermediate products. Buying small quantities of the materials more frequently to produce goods is a more costly affair.

The third reason for holding inventories by the firms is to avoid ‘running out of stock’ possibilities when their sales of goods are high and therefore it is profitable to sell at that time. This requires them to hold inventories of goods.

Determinants of Inventory Investment:

The inventories of raw materials and goods depend on the level of output which a firm plans to produce. An important model that explains the inventories of raw materials and goods is the accelerator model. Though the accelerator model applies to all types of investment, it applies best in case of inventory investment. According to the accelerator model, the firms hold the total stock of inventories of raw materials and goods that is proportional to their level of output.

When manufacturing firms’ level of output is high, they require to keep more inventories of materials and of goods in process of being converted into finished products. When the economy is booming, retail firms would like to hold more inventories so that the goods they are selling may not go out of stock and their customers go away disappointed. Thus, if N stands for the stock of inventories and Y for level of output, then

N = βY

where β is proportion of output (Y) that the firms want to hold as inventories.

Now, since inventory investment (I) means the change in stock of inventories, it can be written as follows:

In = ∆N = β∆Y

The accelerator model predicts that given the parameter β when output of firms increases, inventory investment will increase and when output falls, the inventory investment by firms will decline. In fact, when output of goods falls due to slackening of demand, the firms will allow the inventories to run down which implies negative inventory investment.

The empirical macroeconomic studies made in United States indicated that for every dollar increase in GDP, there is 0.20 of inventory investment. That is, value of β in the accelerator model is 0.2. In quantitative terms, the accelerator model of inventory investment can be written as

In = 0.2 ∆Y

Determinants of Investment:

(1) Expected rate of profits to which Keynes gives the name Marginal Efficiency of Capital, and

(2) The rate of interest. It can be easily shown that investment is determined by expected rate of profit and the rate of interest.

A person having an amount of savings has two alternatives before him. Either he should invest his savings in machines, factories, etc., or he can lend his savings to others on a certain rate of interest. If investment undertaken in machines or factories is expected to fetch 25% rate of profit, while the current rate of interest is only 15%, then it is obvious that the person would invest his savings in machinery or factory.

If investment is to be profitable then the expected rate of profit must not be less than the current market rate of interest. If the expected rate of profit is greater than the market rate of interest, new investment will take place.

If an entrepreneur does not invest his own savings but has to borrow from others, then it becomes much clear that the expected rate of profit from investment in any capital asset must not be less than the rate of interest he has to pay. For instance, if an entrepreneur borrows funds from others at 15% rate of interest, then the investment proposed to be undertaken will actually be undertaken only if the expected rate of profit from it is more than 15 per cent.

We thus see that investment depends upon marginal efficiency of capital on the one hand and the rate of interest on the other. Investment will be undertaken in any given form of capital asset so long as expected rate of profit or marginal efficiency of capital falls to the level of the current market rate of interest. The equilibrium of the entrepreneur is established at the level of investment where expected rate of profit or marginal efficiency of capital is equal to the current rate of interest. Therefore, the theory of investment is also based upon the assumption that the entrepreneur tries to maximize his profits.

Of the two determinants of inducement to invest, marginal efficiency of capital or expected rate of profit is of comparatively greater importance than the rate of interest. This is because rate of interest does not change much in the short run; it is more or less sticky.

But changes in the expectations of profits greatly affect the marginal efficiency of capital and make it very much unstable and volatile. As a result of changes in marginal efficiency of capital, investment demand is greatly affected which causes aggregate demand to fluctuate very much. The changes in aggregate demand bring about economic fluctuations which are generally known as trade cycles.

When profit expectations of businessmen are good, large investment is undertaken which causes aggregate demand to rise and bring about conditions of boom and prosperity in the economy. On the other hand, when expectations regarding profits are adverse, the rate of investment falls which causes decline in aggregate demand and brings about depression, unemployment and excess productive capacity in the economy. Thus, the changes in the marginal efficiency of capital play a crucial role in causing changes in the investment level and economic activity.

The theory of interest that, according to Keynes, the rate of interest is determined by liquidity preference and the supply of money. The greater the liquidity preference, the greater the rate of interest. Given the liquidity preference curve, the greater the supply of money, the lower will be the rate of interest. We have already studied how the rate of interest is determined. We explain below in detail the concept of marginal efficiency of capital and describe the factors on which it depends.

Marginal Efficiency of Capital:

The concept of marginal efficiency of capital refers to the rate of profit expected to be made from investment in certain capital assets. The rate of profit expected from an extra unit of a capital asset is known as marginal efficiency of capital.

Now, the question is how the marginal efficiency of capital is measured. Suppose an entrepreneur invests money in a certain machinery, how will he estimate the expected rate of profit from it. To estimate the marginal efficiency of capital, the entrepreneur will first take into consideration how much price he has to pay for the particular capital asset.

The price which he has to pay for the particular capital asset is called its supply price or cost of capital. The second thing which he will consider is that how much yield he expects to obtain from investment from that particular capital asset. A capital asset continues to produce goods and yield income over a long period of time. Therefore, an entrepreneur has to estimate the prospective yield from a capital asset over his whole life period. Thus, the supply price and the prospective yields of a capital asset determine the marginal efficiency of capital.

By deducting the supply price from the prospective yield during whole life of a capital asset the entrepreneur can estimate the expected rate of profit or marginal efficiency of capital. Keynes has defined the marginal efficiency of capital in the following words: “I define the marginal efficiency of capital as being equal to that rate of discount which would make the present value of the series of annuities given by the returns expected from the capital asset during its life just equal to its supply price.”

Thus, according to Keynes, marginal efficiency of capital is the rate of discount which renders the prospective yields from a capital asset over its whole life period equal to the supply price of that asset.

Therefore, we can obtain the marginal efficiency of capital in the following way:

Supply Price = Discounted Prospective Yields

C = R1/1+r + R2/(1+r)2+ R3/(1+r)3 …………… + Rn/(1+r)n

In the above formula, C stands for Supply Price or Replacement Cost and R1, R2, R3, .. Rn etc., represent the annual prospective yields from the capital asset, r is that rate of discount which renders the annual prospective yields equal to the supply price of the capital asset. Thus, r represents the expected rate of profit or marginal efficiency of capital.

Marginal Efficiency of Capital in General:

We have explained above the marginal efficiency of a particular type of capital asset. But we also require to know the marginal efficiency of capital in general. It is the marginal efficiency of capital in general that will indicate the scope for investment opportunities at a particular time in any economy.

At a particular time in an economy the marginal efficiency of that particular capital asset which yields the greatest rate of profit, is called the marginal efficiency of capital in general. In other words, marginal efficiency of capital in general is the greatest of all the marginal efficiencies of various types of capital assets which could be produced but have not yet been produced. Thus, marginal efficiency of capital in general represents the highest expected rate of return to the community from an extra unit of a capital asset which yields the maximum profit which could be produced.

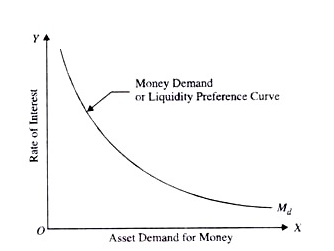

Keeping in view the existing stock of a capital asset, we can always calculate the marginal efficiency of any particular capital asset. The marginal efficiency of capital will vary when more is invested in a given particular capital asset. In any given period of time marginal efficiency of capital from every type of capital asset will decline as more investment is undertaken in it. In other words, marginal efficiency of a particular type of capital asset will be sloping downward as the stock of capital increases.

The main reason for the decline in marginal efficiency of capital with the increase in investment in it is that the prospective yields from capital asset fall as more units are installed and used for production of a good. Prospective yields decline because when more quantity of a good is produced with the greater amount of capital asset prices of goods decline. The second reason for the decline in the marginal efficiency of capital is that the supply price of the capital asset may rise because the increase in demand for it will bring about increase in its cost of production.

Rate of interest and Investment Demand Curve:

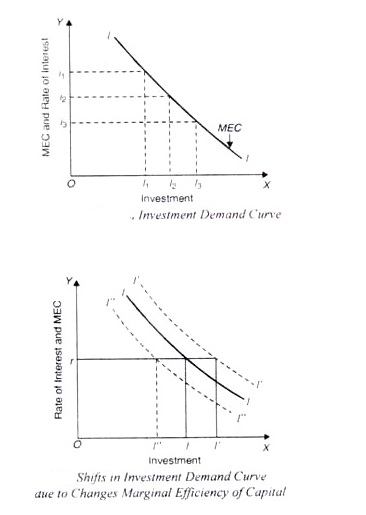

We have explained above how the marginal efficiency of capital is estimated. We can represent diminishing marginal efficiency of capital in general by a curve which will slope downward. This has been done in Fig. below in which along the X-axis investment in capital assets is measured and along the X-axis marginal efficiency of capital in general is shown. It will be seen from the figure that when investment in capital asset is equal to 07,, marginal efficiency of capital is i,. When the investment is increased to OI2, marginal efficiency of capital falls to i2. Likewise, when investment rises to OI3, marginal efficiency of capital further diminishes to i3.

We have seen above that inducement to invest depends upon the marginal efficiency of capital and the rate of interest. With the given particular rate of interest and given the curve of marginal efficiency of capital in general we can show what will be the equilibrium level of investment in the economy. If in Fig along the Y-axis, rate of interest is also shown, then level of investment can be easily determined.

The equilibrium level of investment will be established at the point where marginal efficiency of capital becomes equal to the given current rate of interest. Thus, if the rate of interest is i1 then I1 investment will be undertaken. Since at OI1 level of investment marginal efficiency of capital is equal to the rate of interest i1. If the rate of interest falls to i2, investment in the capital assets will rise to OI2, since at OI2 level of investment the new rate of interest i2 is equal to the marginal efficiency of capital. Thus, we see that the curve of marginal efficiency of capital in general shows the demand for investment or inducement to invest at various rates of interest.

Hence marginal efficiency of capital curve represents the investment demand curve. This investment demand curve shows how much investment will be undertaken by the entrepreneurs at various rates of interest. If the investment demand curve is less elastic, then investment demand will not increase much with the fall in the rate of interest. But if the investment demand curve or marginal efficiency of capital curve is very much elastic, then the changes in the rate of interest will bring about large changes in investment demand.

Key takeaways –

Portfolio and transactions theories of demand for real balances

1. Tobin’s Portfolio Approach to Demand for Money:

An American economist James Tobin, in his important contribution explained that rational behaviour on the part of the individuals is that they should keep a portfolio of assets which consists of both bonds and money. In his analysis he makes a valid assumption that people prefer more wealth to less.

According to him, an investor is faced with a problem of what proportion of his portfolio of financial assets he should keep in the form of money (which earns no interest) and interest-bearing bonds. The portfolio of individuals may also consist of more risky assets such as shares.

According to Tobin, faced with various safe and risky assets, individuals diversify their portfolio by holding a balanced combination of safe and risky assets.

According to Tobin, individual’s behaviour shows risk aversion. That is, they prefer less risk to more risk at a given rate of return. In the Keynes’ analysis an individual holds his wealth in either all money or all bonds depending upon his estimate of the future rate of interest.

But, according to Tobin, individuals are uncertain about future rate of interest. If a wealth holder chooses to hold a greater proportion of risky assets such as bonds in his portfolio, he will be earning a high average return but will bear a higher degree of risk. Tobin argues that a risk averter will not opt for such a portfolio with all risky bonds or a greater proportion of them.

On the other hand, a person who, in his portfolio of wealth, holds only safe and riskless assets such as money (in the form of currency and demand deposits in banks) he will be taking almost zero risk but will also be having no return and as a result there will be no growth of his wealth. Therefore, people generally prefer a mixed diversified portfolio of money, bonds and shares, with each person opting for a little different balance between riskiness and return.

It is important to note that a person will be unwilling to hold all risky assets such as bonds unless he obtains a higher average return on them. In view of the desire of individuals to have both safety and reasonable return, they strike a balance between them and hold a mixed and balanced portfolio consisting of money (which is a safe and riskless asset) and risky assets such as bonds and shares though this balance or mix varies between various individuals depending on their attitude towards risk and hence their trade-off between risk and return.

Tobin‘s Liquidity Preference Function:

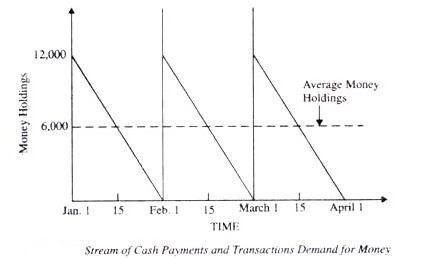

Tobin derived his liquidity preference function depicting relationship between rate of interest and demand for money (that is, preference for holding wealth in money form which is a safe and “riskless” asset. He argues that with the increase in the rate of interest (i.e. rate of return on bonds), wealth holders will be generally attracted to hold a greater fraction of their wealth in bonds and thus reduce their holding of money.

That is, at a higher rate of interest, their demand for holding money (i.e., liquidity) will be less and therefore they will hold more bonds in their portfolio. On the other hand, at a lower rate of interest they will hold more money and less bonds in their portfolio.

This means, like the Keynes’s speculative demand for money, in Tobin’s portfolio approach demand function for money as an asset (i.e. his liquidity preference function curve) slopes downwards as is shown in Fig. below, where on the horizontal axis asset demand for money is shown. This downward-sloping liquidity preference function curve shows that the asset demand for money in the portfolio increases as the rate of interest on bonds falls.

In this way Tobin derives the aggregate liquidity preference curve by determining the effects of changes in interest rate on the asset demand for money in the portfolio of individuals. Tobin’s liquidity preference theory has been found to be true by the empirical studies conducted to measure interest elasticity of the demand for money.

As shown by Tobin through his portfolio approach, these empirical studies reveal that aggregate liquidity preference curve is negatively sloped. This means that most of the people in the economy have liquidity preference function similar to the one shown by curve Md in Fig. below

Evaluation:

Tobin’s approach has done away with the limitation of Keynes’ theory of liquidity preference for speculative motive, namely, individuals hold their wealth in either all money or all bonds. Thus, Tobin’s approach, according to which individuals simultaneously hold both money and bonds but in different proportion at different rates of interest yields a continuous liquidity preference curve.

Further, Tobin’s analysis of simultaneous holding of money and bonds is not based on the erroneous Keynes’s assumption that interest rate will move only in one direction but on a simple fact that individuals do not know with certainty which way the interest rate will change.

It is worth mentioning that Tobin’s portfolio approach, according to which liquidity preference (i.e. demand for money) is determined by the individual’s attitude towards risk, can be extended to the problem of asset choice when there are several alternative assets, not just two, of money and bonds.

2. Baumol’s Inventory Approach to Transactions Demand for Money:

Instead of Keynes’s speculative demand for money, Baumol concentrated on transactions demand for money and put forward a new approach to explain it. Baumol explains the transaction demand for money from the viewpoint of the inventory control or inventory management similar to the inventory management of goods and materials by business firms.

As businessmen keep inventories of goods and materials to facilitate transactions or exchange in the context of changes in demand for them, Baumol asserts that individuals also hold inventory of money because this facilitates transactions (i.e. purchases) of goods and services.

In view of the cost incurred on holding inventories of goods there is need for keeping optimal inventory of goods to reduce cost. Similarly, individuals have to keep optimum inventory of money for transaction purposes. Individuals also incur cost when they hold inventories of money for transactions purposes.

They incur cost on these inventories as they have to forgone interest which they could have earned if they had kept their wealth in saving deposits or fixed deposits or invested in bonds. This interest income forgone is the cost of holding money for transactions purposes. In this way Baumol and Tobin emphasised that transaction demand for money is not independent of the rate of interest.

It may be noted that by money we mean currency and demand deposits which are quite safe and riskless but carry no interest. On the other hand, bonds yield interest or return but are risky and may involve capital loss if wealth holders invest in them.

However, saving deposits in banks, according to Baumol, are quite free from risk and also yield some interest. Therefore, Baumol asks the question why an individual holds money (i.e. currency and demand deposits) instead of keeping his wealth in saving deposits which are quite safe and earn some interest as well.

According to him, it is for convenience and capability of it being easily used for transactions of goods that people hold money with them in preference to the saving deposits. Unlike Keynes both Baumol and Tobin argue that transactions demand for money depends on the rate of interest.

People hold money for transaction purposes “to bridge the gap between the receipt of income and its spending.” As interest rate on saving deposits goes up people will tend to shift a part of their money holdings to the interest-bearing saving deposits.

Individuals compare the costs and benefits of funds in the form of money with the interest- bearing saving deposits. According to Baumol, the cost which people incur when they hold funds in money is the opportunity cost of these funds, that is, interest income forgone by not putting them in saving deposits.

Baumol’s Analysis of Transactions Demand:

A Baumol analysis the transactions demand for money of an individual who receives income at a specified interval, say every month, and spends it gradually at a steady rate. This is illustrated in Fig. below. It is assumed that individual is paid Rs. 12000 salary cheque on the first day of each month.

Suppose he gets it cashed (i.e. converted into money) on the very first day and gradually spends it daily throughout the month. (Rs. 400 per day) so that at the end of the month he is left with no money. It can be easily seen that his average money holding in the month will be Rs. = 12000/2 = Rs. 6,000 (before 15th of a month he will be having more than Rs. 6,000 and after 15th day he will have less than Rs. 6,000).Stream of Cash Payments and Transactions Demand for Money

Average holding of money equal to Rs. 6,000 has been shown by the dotted line. Now, the question arises whether it is the optimal strategy of managing money or what is called optimal cash management. The simple answer is no. This is because the individual is losing interest which he could have earned if he had deposited some funds in interest-bearing saving deposits instead of withdrawing all his salary in cash on the first day.

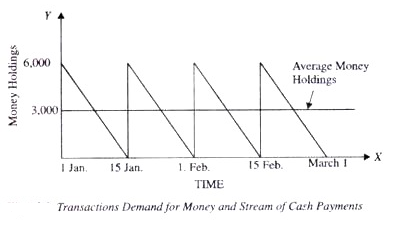

He can manage his money balances so as to earn some interest income as well. Suppose, instead of withdrawing his entire salary on the first day of a month, he withdraws only half of it i.e. (Rs. 6,000 in cash and deposits the remaining amount of Rs. 6,000 in saving account which gives him interest of 5 per cent, his expenditure per day remaining constant at Rs. 400.

This is illustrated in Fig. below It will be seen that his money holdings of Rs. 6,000 will be reduced to zero at the end of the 15th day of each month. Now, he can withdraw Rs. 6,000 on the morning of 16th of each month and then spends it gradually, at a steady rate of 400 per day for the next 15 days of a month. This is a better method of managing funds as he will be earning interest on Rs. 6,000 for 15 days in each month. Average money holdings in this money management scheme is Rs. 6000/2 = 3000Transactions Demand for Money and Stream of Cash Payments

Likewise, the individual may decide to withdraw Rs. 4,000 (i.e., 1/3rd of his salary) on the first day of each month and deposits Rs. 8,000 in the saving deposits. His Rs. 4,000 will be reduced to zero, as he spends his money on transactions, (that is, buying of goods and services) at the end of the 10th day and on the morning of 11th of each month he again withdraws Rs. 4,000 to spend on goods and services till the end of the 20th day and on 21st day of the month he again withdraws Rs. 4,000 to spend steadily till the end of the month. In this scheme on an average he will be holding Rs. 4000/2 = 2000 and will be investing remaining funds in saving deposits and earn interest on them. Thus, in this scheme he will be earning more interest income.

Now, which scheme will he decide to adopt? It may be noted that investing in saving deposits and then withdrawing cash from it to meet the transactions demand involves cost also. Cost on brokerage fee is incurred when one invests in interest-bearing bonds and sells them.

Even in case of saving deposits, the asset which we are taking for illustration, one has to spend on transportation costs for making extra trips to the bank for withdrawing money from the Savings Account. Besides, one has to spend time in the waiting line in the bank to withdraw cash each time from the saving deposits.

Thus, the greater the number of times an individual makes trips to the bank for withdrawing money, the greater the broker’s fee he will incur. If he withdraws more cash, he will be avoiding some costs on account of brokerage fee.

Thus, individual faces a trade-off problem-, the greater the amount of pay cheque he withdraws in cash, less the cost on account of broker’s fee but the greater the opportunity cost of forgoing interest income. The problem is therefore to determine an optimum amount of money to hold. Baumol has shown that optimal amount of money holding is determined by minimising the cost of interest income forgone and broker’s fee.

Supply of money

Money supply refers to the amount of money which is in circulation in an economy at any given time. It is the total stock of money held by the people consisting of individuals, firms, State and its constituent bodies except the State treasury, Central Bank and Commercial Banks.

Professor Friedman defines the money supply at any moment of time as “literally the number of dollars people are carrying around in their pockets, the number of dollars they have to their credit at banks or dollars they have to their credit at banks in the form of demand deposits, and also commercial bank time deposits.”

Money supply is an important factor for the economic development and priced stability in the economy. Money supply denoted as M1, means demand deposit with commercial bank plus currency with the public.

Money supply has wider definition characterized as M2 and M3, M2 definition includes M1 plus time deposits of commercial banks in the supply of money. M3 includes M2 plus deposits of savings banks, building societies, loan associations, and deposits of other credit and financial institutions.

Determinants of money supply

Key takeaways –

Sources-

1. Ahuja H.L – Macro Economics – S.Chand.

2. Mankiw, N. Gregory. Principles Macroeconomics.Cengage Learning.

3. Dornbusch, Rudiger, and Stanley. Fischer, Macroeconomics. McGraw-Hill.

4. Dornbusch, Rudiger., Stanley. Fischer and Richard Startz, Macroeconomics. Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

5. Deepashree, Macro Economics, Scholar Tech. New Delhi.

6. Barro, Robert, J. Macroeconomics, MIT Press, Cambridge MA.