Unit-1

Money

Q1) Explain meaning and function of money.

A1) Meaning:-

Money may be anything chosen as the medium of exchange. According to some economist money is anything that performs the function of money. It is something which is widely accepted in payment for goods and services and in settlement of debts. In a modern society for commodities are expressed and valued in terms of money. In a wider sense, the term money includes all medium of exchange – Gold, Silver, Copper, Paper, Cheques, Commercial Bills of exchange, etc.

Functions of Money:-

Money performs various functions. Mainly the functions of money can be classified into three groups’ namely

(i) Primary functions

(ii) Secondary function

(iii) Contingent functions

1) Primary function: Primary functions are basic or fundamental function of money. Infact, they are the original functions of money which ensure smooth working of the economy. Following are the primary functions:

a) Medium of exchange: Money acts as an effective medium of exchange. It facilitates exchange of goods and services. Everything is bought and sold with help of money. By performing as the medium of exchange, money removes the difficulties of barter system.

b) Measure of value: Money serves as a common measure of value. The value of all goods and services are measured in terms of money. In other words, pieces of all goods and services are expressed in terms money. The pricing system unable a compare the value of different goods and services and each the right choice.

2) Secondary function: Secondary functions are those functions which are derived from primary function.

a) Standard of deferred payment: Money acts as an effective standard of deferred payments. Deferred payments refer to payment to be made in future. Deferred payments have become the day to day activity in modern society. Money facilitates all kinds of credit transactions. Both, borrowings as well as lending are done in terms of money. All kinds of Hire purchase transactions are carried out in terms of money. As money enjoys the attributes of stability, Durability and General acceptability, it acts as a better standard of deferred payments.

b) Store of value: Money serves as a store of value. Savings were discouraged under the barter system due to lack of store of value. With inventions of money, it is possible to save. At present all savings are done in terms of money. Bank deposits represent the savings of the people. Moreover, money can be easily converted into any other Marketable assets like Land, Machinery, Plant, etc. Thus it facilitates capital accumulation. Money being the most liquid assets, it acts as a better store of value than any other assets.

c) Transfer of value: Money acts as a means of transferring purchasing power. Money facilitates transfer of value from one person to another person & one place to another place. As money enjoys general acceptability, a person can dispose of his property in Delhi and purchase new property at Mumbai. Instrument like cheques and bank drafts enable such transfer easy and quick.

3) Contingent function: In additions to the above functions, money has to performs certain special function known as contingent functions –

Q2) Explain classical approach.

A2) The Classical Approach:

The classical economists didn't explicitly formulate demand for money theory but their views are inherent within the quantity theory of money. They emphasized the transactions demand for money in terms of the rate of circulation of cash .this is often because money acts as a medium of exchange and facilitates the exchange of products and services. In Fisher’s “Equation of Exchange”.

MV=PT

Where M is that the total quantity of cash, V is its velocity of circulation, P is that the price level, and T is that the total amount of goods and services exchanged for money.

The right hand side of this equation PT represents the demand for money which, in fact, “depends upon the worth of the transactions to be undertaken within the economy, and is adequate to a constant fraction of these transactions.” MV represents the supply of money which is given and in equilibrium equals the demand for money. Thus the equation becomes

Md = PT

This transactions demand for money, in turn, is decided by the extent of full employment income. this is often because the classicists believed in Say’s Law whereby supply created its own demand, assuming the full employment level of income. Thus the demand for money in Fisher’s approach may be a constant proportion of the extent of transactions, which successively , bears a continuing relationship to the extent of value . Further, the demand for money is linked to the volume of trade happening in an economy at any time.

Thus its underlying assumption is that individuals hold money to buy goods.

But people also hold money for other reasons, like to earn interest and to supply against unforeseen events. it's therefore, impracticable to say that V will remain constant when M is modified . the foremost important thing about money in Fisher’s theory is that it's transferable. But it doesn't explain fully why people hold money. It doesn't clarify whether to incorporate as money such items as time deposits or savings deposits that aren't immediately available to pay debts without first being converted into currency.

It was the Cambridge cash balance approach which raised an extra question: Why do people actually want to carry their assets within the form of money? With larger incomes, people want to form larger volumes of transactions which larger cash balances will, therefore, be demanded.

The Cambridge demand equation for money is-

Md=kPY

where Md is that the demand for money which must equal the supply to money (Md=Ms) in equilibrium within the economy, k is that the fraction of the important money income (PY) which individuals wish to carry in cash and demand deposits or the ratio of money stock to income, P is that the price level, and Y is that the aggregate real income. This equation tells us that “other things being equal, the demand for money in normal terms would be proportional to the nominal level of income for every individual, and hence for the mixture economy also .”

Critical Evaluation:

This approach includes time and saving deposits and other convertible funds within the demand for money. It also stresses the importance of factors that make money more or less useful, like the costs of holding it, uncertainty about the future then on. But it says little about the character of the relationship that one expects to prevail between its variables, and it doesn't say too much about which ones could be important.

One of its major criticisms arises from the neglect of store useful function of cash . The classicists emphasized only the medium of exchange function of money which simply acted as a go-between to facilitate buying and selling. For them, money performed a neutral role within the economy. it had been barren and wouldn't multiply, if stored within the form of wealth.

This was an erroneous view because money performed the “asset” function when it's transformed into other sorts of assets like bills, equities, debentures, real assets (houses, cars, TVs, then on), etc. Thus the neglect of the asset function of cash was the main weakness of classical approach to the demand for money which Keynes remedied.

Q3) Explain Keynesian Approach.

A3) The Keynesian Approach: Liquidity Preference:

Keynes in his General Theory used a replacement term “liquidity preference” for the demand for money. Keynes suggested three motives which led to the demand for money in an economy: (1) the transactions demand, (2) the precautionary demand, and (3) the speculative demand.

The Transactions Demand for Money:

The transactions demand for money arises from the medium of exchange function of money in making regular payments for goods and services. consistent with Keynes, it relates to “the need of money for the present transactions of private and business exchange” it's further divided into income and business motives. The income motive is supposed “to bridge the interval between the receipt of income and its disbursement.”

Similarly, the business motive is supposed “to bridge the interval between the time of incurring business costs which of the receipt of the sale proceeds.” If the time between the incurring of expenditure and receipt of income is little , less cash are going to be held by the people for current transactions, and the other way around . there'll , however, be changes within the transactions demand for money depending upon the expectations of income recipients and businessmen. They depend on the level of income, the rate of interest, the business turnover, the traditional period between the receipt and disbursement of income, etc.

Given these factors, the transactions demand for money may be a direct proportional and positive function of the extent of income, and is expressed as

L1 = kY

Where L1 is that the transactions demand for money, k is that the proportion of income which is kept for transactions purposes, and Y is that the income.

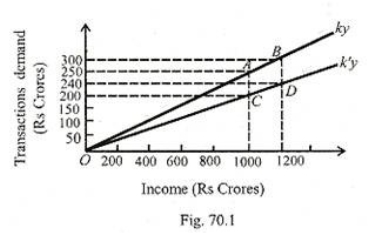

This equation is illustrated in Figure 70.1 where the line kY represents a linear and proportional relation between transactions demand and therefore the level of income. Assuming k= 1/4 and income Rs 1000 crores, the demand for transactions balances would be Rs 250 crores, at point A. With the rise in income to Rs 1200 crores, the transactions demand would be Rs 300 crores at point В on the curve kY.

If the transactions demand falls because of a change in the institutional and structural conditions of the economy, the value of к is reduced to mention , 1/5, and therefore the new transactions demand curve is kY. It shows that for income of Rs 1000 and 1200 crores, transactions balances would Rs 200 and 240 crores at points С and D respectively within the figure. “Thus we conclude that the chief determinant of changes within the actual amount of the transactions balances held is changes in income. Changes within the transactions balances are the results of movements along a line like kY instead of changes within the slope of the line. Within the equation, changes in transactions balances are the results of changes in Y instead of changes in k.”

Interest Rate and Transactions Demand:

Regarding the rate of interest because the determinant of the transactions demand for money Keynes made the LT function interest inelastic. But the acknowledged that the “demand for money within the active circulation is additionally the some extent a function of the rate of interest, since a higher rate of interest may cause a more economical use of active balances.” “However, he didn't stress the role of the rate of interest during this a part of his analysis, and lots of of his popularizes ignored it altogether.” In recent years, two post-Keynesian economists William J. Baumol and James Tobin have shown that the rate of interest is a crucial determinant of transactions demand for money.

They have also pointed out the relationship, between transactions demand for money and income isn't linear and proportional. Rather, changes in income result in proportionately smaller changes in transactions demand.

Transactions balances are held because income received once a month isn't spent on the same day. In fact, a private spreads his expenditure evenly over the month. Thus some of cash meant for transactions purposes are often spent on short-term interest-yielding securities. it's possible to “put funds to figure for a matter of days, weeks, or months in interest-bearing securities like U.S. Treasury bills or commercial paper and other short-term money market instruments.

The problem here is that there's a cost involved in buying and selling. One must weigh the financial cost and inconvenience of frequent entry to and exit from the market for securities against the apparent advantage of holding interest-bearing securities in situ of idle transactions balances.

Among other things, the value per purchase and sale, the speed of interest, and therefore the frequency of purchases and sales determine the profitability of switching from ideal transactions balances to earning assets. Nonetheless, with the value per purchase and sale given, there's clearly some rate of interest at which it becomes profitable to modify what otherwise would be transactions balances into interest-bearing securities, albeit the amount that these funds could also be spared from transactions needs is measured only in weeks. the higher the rate of interest , the larger will be the fraction of any given amount of transactions balances which will be profitably diverted into securities.”

The structure of cash and short-term bond holdings is shown in Figure 70.2 (A), (B) and (C). Suppose a private receives Rs 1200 as income on the first of every month and spends it evenly over the month. The month has four weeks. His saving is zero.

Accordingly, his transactions demand for money in each week is Rs 300. So he has Rs 900 idle money within the first week, Rs 600 within the second week, and Rs 300 within the third week. He will, therefore, convert this idle money into interest bearing bonds, as illustrated in Panel (B) and (C) of Figure 70.2. He keeps and spends Rs 300 during the first week (shown in Panel B), and invests Rs 900 in interest-bearing bonds (shown in Panel C). On the primary day of the second week he sells bonds worth Rs. 300 to cover cash transactions of the second week and his bond holdings are reduced to Rs 600.

Similarly, he will sell bonds worth Rs 300 within the beginning of the third and keep the remaining bonds amounting to Rs 300 which he will sell on the first day of the fourth week to satisfy his expenses for the last week of the month. the amount of cash held for transactions purposes by the individual during each week is shown in saw-tooth pattern in Panel (B), and therefore the bond holdings in each week are shown in blocks in Panel (C) of Figure 70.2.

The modern view is that the transactions demand for money is a function of both income and interest rates which may be expressed as

L1 = f (Y, r).

This relationship between income and rate of interest and therefore the transactions demand for money for the economy as an entire is illustrated in Figure 3. We saw above that LT = kY. If y=Rs 1200 crores and k= 1/4, then LT = Rs 300 crores.

This is shown as Y1 curve in Figure 70.3. If the income level rises to Rs 1600 crores, the transactions demand also increases to Rs 400 crores, given k = 1/4. Consequently, the transactions demand curve shifts to Y2. The transactions demand curves Y1, and Y2 are interest- inelastic so long because the rate of interest doesn't rise above r8 per cent.

As the rate of interest starts rising above r8, the transactions demand for money becomes interest elastic. It indicates that “given the cost of switching into and out of securities, an rate of interest above 8 per cent is sufficiently high to draw in some amount of transaction balances into securities.” The backward slope of the K, curve shows that at still higher rates, the transaction demand for money declines.

Thus when the rate of interest rises to r12, the transactions demand declines to Rs 250 crores with an income level of Rs 1200 crores. Similarly, when the value is Rs 1600 crores the transactions demand would decline to Rs 350 crores at r12 rate of interest . Thus the transactions demand for money varies directly with the level of income and inversely with the speed of interest.

The Precautionary Demand for Money:

The Precautionary motive relates to “the desire to produce for contingencies requiring sudden expenditures and for unforeseen opportunities of advantageous purchases.” Both individuals and businessmen keep take advantage reserve to satisfy unexpected needs. Individuals hold some cash to supply for illness, accidents, unemployment and other unforeseen contingencies.

Similarly, businessmen keep cash in reserve to tide over unfavourable conditions or to gain from unexpected deals. Therefore, “money held under the precautionary motive is very like water kept in reserve during a water tank.” The precautionary demand for money depends upon the level of income, and business activity, opportunities for unexpected profitable deals, availability of cash, the cost of holding liquid assets in bank reserves, etc.

Keynes held that the precautionary demand for money, like transactions demand, was a function of the extent of income. But the post-Keynesian economists believe that like transactions demand, it's inversely associated with high interest rates. The transactions and precautionary demand for money are going to be unstable, particularly if the economy isn't at full employment level and transactions are, therefore, but the maximum, and are liable to fluctuate up or down.

Since precautionary demand, like transactions demand may be a function of income and interest rates, the demand for money for these two purposes is expressed within the single equation LT=f(Y, r)9. Thus the precautionary demand for money also can be explained diagrammatically in terms of Figures 2 and three .

The Speculative Demand for Money:

The speculative (or asset or liquidity preference) demand for money is for securing profit from knowing better than the market what the longer term will bring forth”. Individuals and businessmen having funds, after keeping enough for transactions and precautionary purposes, wish to make a speculative gain by investing fettered . Money held for speculative purposes may be a liquid store of value which may be invested at an opportune moment in interest-bearing bonds or securities.

Bond prices and therefore the rate of interest are inversely associated with one another . Low bond prices are indicative of high interest rates, and high bond prices reflect low interest rates. A bond carries a fixed rate of interest. as an example , if a bond of the worth of Rs 100 carries 4 per cent interest and therefore the market rate of interest rises to eight per cent, the worth of this bond falls to Rs 50 within the market. If the market rate of interest falls to 2 per cent, the value of the bond will rise to Rs 200 within the market.

This can be figured out with the assistance of the equation

V = R/r

Where V is that the current market value of a bond, R is that the annual return on the bond, and r is that the rate of return currently earned or the market rate of interest. So a bond worth Rs 100 (V) and carrying a 4 per cent rate of interest (r), gets an annual return (R) of Rs 4, that is,

V=Rs 4/0.04=Rs 100. When the market rate of interest rises to 8 per cent, then V=Rs 4/0.08=Rs50; when it fall to 2 per cent, then V=Rs 4/0.02=Rs 200.

Thus individuals and businessmen can gain by buying bonds worth Rs 100 each at the market value of Rs 50 each when the rate of interest is high (8 per cent), and sell them again once they are dearer (Rs 200 each when the speed of interest falls (to 2 per cent).

According to Keynes, it's expectations about changes in bond prices or within the current market rate of interest that determine the speculative demand for money. In explaining the speculative demand for money, Keynes had a normal or critical rate of interest (rc) in mind. If the present rate of interest (r) is above the “critical” rate of interest, businessmen expect it to fall and bond price to rise. They will, therefore, buy bonds to sell them in future when their prices rise so as to realize thereby. At such times, the speculative demand for money would fall. Conversely, if the present rate of interest happens to be below the critical rate, businessmen expect it to rise and bond prices to fall. They will, therefore, sell bonds within the present if they have any, and therefore the speculative demand for money would increase.

Thus when r > r0, an investor holds all his liquid assets in bonds, and when r < r0 his entire holdings enter money. But when r = r0, he becomes indifferent to carry bonds or money.

Thus relationship between an individual’s demand for money and therefore the rate of interest is shown in Figure 70.4 where the horizontal axis shows the individual’s demand for money for speculative purposes and therefore the current and important interest rates on the vertical axis. The figure shows that when r is larger than r0, the asset holder puts all his cash balances in bonds and his demand for money is zero.

This is illustrated by the LM portion of the vertical axis. When r falls below r0, the individual expects more capital losses on bonds as against the interest yield. He, therefore, converts his entire holdings into money, as shown by OW within the figure. This relationship between an individual asset holder’s demand for money and therefore the current rate of interest gives the discontinuous step demand for money curve LMSW.

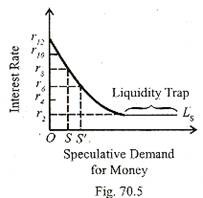

For the economy as an entire the individual demand curve are often aggregated on this presumption that individual asset-holders differ in their critical rates r0. it's smooth curve which slopes downward from left to right, as shown in Figure 70.5.

Thus the speculative demand for money is a decreasing function of the rate of interest. the higher the rate of interest, the lower the speculative demand for money and therefore the lower the rate of interest, the higher the speculative demand for money. It are often expressed algebraically as Ls = f (r), where Ls is that the speculative demand for money and r is that the rate of interest.

Geometrically, it's shows in Figure 70.5. The figure shows that at a very high rate of interest rJ2, the speculative demand for money is zero and businessmen invest their cash holdings fettered because they believe that the rate of interest cannot rise further. because the rate of interest falls to say, r8 the speculative demand for money is OS. With a further fall within the rate of interest to r6, it rises to OS’. Thus the form of the Ls curve shows that because the rate of interest rises, the speculative demand for money declines; and with the fall in the rate of interest , it increases. Thus the Keynesian speculative demand for money function is very volatile, depending upon the behaviour of interest rates.

Liquidity Trap:

Keynes visualized conditions during which the speculative demand for money would be highly or maybe totally elastic so that changes within the quantity of money would be fully absorbed into speculative balances. this is often the famous Keynesian liquidity trap. during this case, changes within the quantity of money have no effects in the least on prices or income. according to Keynes, this is often likely to happen when the market rate of interest is very low in order that yields on bond, equities and other securities also will be low.

At a really low rate of interest, like r2, the Ls curve becomes perfectly elastic and therefore the speculative demand for money is infinitely elastic. This portion of the Ls curve is known as the liquidity trap. At such a low rate, people prefer to keep money in cash instead of invest fettered because purchasing bonds will mean a definite loss. People won't buy bonds so long as the rate of interest remain at the low level and that they will be expecting the speed of interest to return to the “normal” level and bond prices to fall.

According to Keynes, because the rate of interest approaches zero, the risk of loss in holding bonds becomes greater. “When the price of bonds has been bid up so high that the rate of interest is, say, only 2 per cent or less, a really small decline within the price of bonds will wipe out the yield entirely and a rather further decline would result in loss of the a part of the principal.” Thus the lower the rate of interest , the smaller the earnings from bonds. Therefore, the greater the demand for cash holdings. Consequently, the Ls curve will become perfectly elastic.

Further, consistent with Keynes, “a long-term rate of interest of two per cent leaves more to fear than to hope, and offers, at an equivalent time, a running yield which is only sufficient to offset a really small measure of fear.” This makes the Ls curve “virtually absolute within the sense that almost everybody prefers cash to holding a debt which yields so low a rate of interest.”

Prof. Modigliani believes that an infinitely elastic Ls curve is possible in a period of great uncertainty when price reductions are anticipated and therefore the tendency to invest in bonds decreases, or if there prevails “a real scarcity of investment outlets that are profitable at rates of interest above the institutional minimum.”

The phenomenon of liquidity trap possesses certain important implications.

First, the monetary authority cannot influence the rate of interest even by following a cheap money policy. a rise within the quantity of cash cannot lead to a further decline within the rate of interest during a liquidity-trap situation. Second, the rate of interest cannot fall to zero.

Third, the policy of a general wage cut can't be efficacious within the face of a perfectly elastic liquidity preference curve, like Ls in Figure 70.5. No doubt, a policy of general wage cut would lower wages and prices, and thus release money from transactions to speculative purpose, the rate of interest would remain unaffected because people would hold money due to the prevalent uncertainty within the money market. Last, if new money is made , it instantly goes into speculative balances and is put into bank vaults or cash boxes rather than being invested. Thus there's no effect on income. Income can change with none change in the quantity of money. Thus monetary changes have a weak effect on economic activity under conditions of absolute liquidity preference.

The Total Demand for Money:

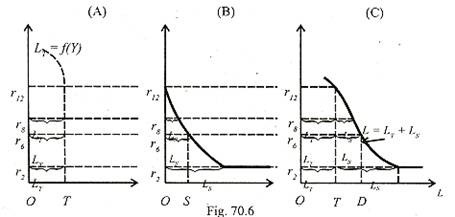

According to Keynes, money held for transactions and precautionary purposes is primarily a function of the extent of income, LT=f (F), and therefore the speculative demand for money may be a function of the rate of interest, Ls = f (r). Thus the total demand for money may be a function of both income and therefore the interest rate:

LT + LS = f (Y) + f (r)

or L = f (Y) + f (r)

or L=f (Y, r)

Where L represents the entire demand for money.

Thus the entire demand for money can be derived by the lateral summation of the demand function for transactions and precautionary purposes and therefore the demand function for speculative purposes, as illustrated in Figure 70.6 (A), (B) and (C). Panel (A) of the Figure shows ОТ, the transactions and precautionary demand for money at Y level of income and different rates of interest. Panel (B) shows the speculative demand for money at various rates of interest. it's an inverse function of the rate of interest.

For instance, at r6 rate of interest it's OS and as the rate of interest falls to r the Ls curve becomes perfectly elastic. Panel (C) shows the entire demand curve for money L which may be a lateral summation of LT and Ls curves: L=LT+LS. for example, at rb rate of interest, the entire demand for money is OD which is that the sum of transactions and precautionary demand ОТ plus the speculative demand TD, OD=OT+TD. At r2 rate of interest , the total demand for money curve also becomes perfectly elastic, showing the position of liquidity trap.

Q4) Explain supply of money.

A4) Definition of money Supply:

The supply of money is a stock at a specific point of time, though it conveys the idea of a flow over time. The term ‘the supply of money’ is synonymous with such terms as ‘money stock’, ‘stock of money’, ‘money supply’ and ‘quantity of money’. the supply of money at any moment is that the total amount of money within the economy.

There are three alternative views regarding the definition or measures of money supply. The foremost common view is related to the traditional and Keynesian thinking which stresses the medium of exchange function of cash. Consistent with this view, money supply is defined as currency with the general public and demand deposits with commercial banks.

Demand deposits are savings and current accounts of depositors in a commercial bank. They’re the liquid kind of money because depositors can draw cheques for any amount lying in their accounts and therefore the bank has got to make cash on demand. Demand deposits with commercial banks plus currency with the general public are together denoted as M1, the money supply. this is often considered a narrower definition of the cash supply.

The second definition is broader and is related to the modem quantity theorists headed by Friedman. Professor Friedman defines the cash supply at any moment of time as “literally the number of dollars people are carrying around in their pockets, the number of dollars they need to their credit at banks or dollars they need to their credit at banks in the form of demand deposits, and also commercial bank time deposits.” Time deposits are fixed deposits of customers in a commercial bank. Such deposits earn a fixed rate of interest varying with the period of time that the amount is deposited. Money can be withdrawn before the expiry of that period by paying a penal rate of interest to the bank.

So time deposits possess liquidity and are included within the money supply by Friedman. Thus this definition includes M1 plus time deposits of economic banks within the supply of cash . This wider definition is characterised as M2 in America and M3 in Britain and India. It stresses the store useful function of money or what Friedman says, ‘a temporary abode of purchasing power’.

The third definition is that the broadest and is related to Gurley and Shaw. They include within the supply of money, M2 plus deposits of savings banks, building societies, loan associations, and deposits of other credit and financial institutions.

The choice between these alternative definitions of the money supply depends on two considerations. One a particular choice of definition may facilitate or blur the analysis of the varied motives for holding cash; and two from the point of view of monetary policy, an appropriate definition should include the world over which the monetary authorities can have direct influence. If these two criteria are applied, none of the three definitions is wholly satisfactory.

The first definition of money supply could also be analytically better because M1 may be a sure medium of exchange. But M1 is an inferior store useful because it earns no rate of interest, as is earned by time deposits. Further, the central bank can have control over a narrower area if only demand deposits are included in the funds

The second definition that has time deposits (M,) within the supply of money is less satisfactory analytically because “in a highly developed financial structure, it's important to consider separately the motives for holding means of payment and time deposits.” Unlike demand deposits, time deposits aren't a prefect liquid sort of money.

This is because the amount lying in them are often withdrawn immediately by cheques. Normally, it can't be withdrawn before the due date of expiry of deposit. just in case a depositor wants his money earlier, he has to provides a notice to the bank which allows the withdrawal after charging a penal rate of interest from the depositor.

Thus time deposits lack perfect liquidity and can't be included within the money supply. But this definition is more appropriate from the purpose of view of monetary policy because the central bank can exercise control over a wider area that has both demand and time deposits held by commercial banks.

The third definition of cash supply that includes M2 plus deposits of non-bank financial institutions is unsatisfactory on both the standards. Firstly, they do not serve the medium of exchange function of cash. Secondly, they almost remain outside the area of control of the central bank. The sole advantage they possess is that they're highly liquid store useful. Despite this merit, deposits of nonbank financial institutions aren't included in the definition of money supply.

Q5) Explain Credit Creation of Commercial Banks.

A5) Credit Creation of Commercial Banks:

The process of credit creation is said to be one of the most important of the functions that are performed by a commercial bank.

A central bank is the primary source of money supply in an economy through circulation of currency. It ensures the availability of currency for meeting the transaction needs of an economy and facilitating various economic activities, such as production, distribution, and consumption. However, for this purpose, the central bank needs to depend upon the reserves of commercial banks. These reserves of commercial banks are the secondary source of money supply in an economy. The most important function of a commercial bank is the creation of credit. Therefore, money supplied by commercial banks is called credit money.

Commercial banks create credit by advancing loans and purchasing securities. They lend money to individuals and businesses out of deposits accepted from the public. However, commercial banks cannot use the entire amount of public deposits for lending purposes. They are required to keep a certain amount as reserve with the central bank for serving the cash requirements of depositors. After keeping the required amount of reserves, commercial banks can lend the remaining portion of public deposits.

Formula for determining the Credit creation

The following formulae can be used to determine the total credit creation

Total Credit Creation = Original Deposit ✕ Credit Multiplier Coefficient

Where,

Credit multiplier coefficient= 1 / r

r = Cash reserve requirement also known as Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR)

Let’s understand this with an example

If the money deposited in bank is Rs.10000 and the bank has a CRR of 10%, then Credit multiplier coefficient will be

Credit multiplier coefficient = 1 / 10%

= 1/ 0.1

= 10

Total Credit Creation = 10000 ✕ 10 = 100000

Similarly, if CRR = 20 %

Then

Credit multiplier coefficient = 1 / 20%

= 1/ 0.2

= 5

Therefore, Total Credit Creation = 10000 ✕ 5 = 50000

From the above values we can understand that low CRR value results in high credit creation and high CRR results in less credit creation. Therefore, with the help of credit creation, money gets multiplied in the economy.

Q6) Explain money measure by RBI.

A6) In the year 1977 central bank of India, i.e. RBI introduced four components of the money supply. The purpose of these four components is to measure the quantity and variation of the money supply. These components are M1, M2, M3 and M4.

These four alternative measures of money supply are labeled M1, M2, M3 and M4. The RBI will collect data and calculate and publish figures of all the four measures. Let us take a look at how they are calculated.

Measures of Money supply = M1 + M2 + M3 + M4

M1 (Narrow Money)

M1 includes all the currency notes being held by the public on any given day. It also includes all the demand deposits with all the banks in the country, both savings as well as current account deposits. It also includes all the other deposits of the banks kept with the RBI. So M1 = CC + DD + Other Deposits

M2

M2, also narrow money, includes all the inclusions of M1 and additionally also includes the saving deposits of the post office banks. So M2 = M1 + Savings Deposits of Post Office Savings

M3 (Broad Money)

M3 consists of all currency notes held by the public, all demand deposits with the bank, deposits of all the banks with the RBI and the net Time Deposits of all the banks in the country. So M3 = M1 + time deposits of banks.

M4

M4 is the widest measure of money supply that the RBI uses. It includes all the aspects of M3 and also includes the savings of the post office banks of the country. It is the least liquid measure of all of them. M4 = M3 + Post office savings

Q7) Explain credit control methods.

A7) Credit control also means that monetary management or Instrument of monetary policy. Central Bank controls the credit by using two methods –

A) Quantitative Method: It refers to the steps aimed at controlling credit by checking the quantity of money in circulation.

1) Bank rate policy: Bank rate is the rate at which Central Bank rediscount bill of commercial Banks and provides financial assistance to commercial bank.

During inflation Central Bank follows the Dear money policy. It increases the bank rate & thereby makes borrowing costly. This will discourage the commercial bank from the obtaining funds from the Central Bank. When Bank rate increases, the rate of interest prevailing in the money market will also increase. The borrowers will have to pay high rate of interest and their tendency to demand credit will decline. It leads to contraction of supply of credit money and reduces investment. Such reduction in business activities results in contraction of factor rewards which in turn in brings the effective demand down. As demand declines price will fall and inflation is controlled.

During deflation the bank will follow, Cheap money policy and the bank rate will be reduced. As a result the rate of interest collected by the Commercial Banks will also fall. This encourages the business community to demand more loans and it leads to expansion of credit. This would put deflation under check.

2) Open market policy: It refers to buying and selling of securities and other eligible papers by central bank in the open Market.

Central Bank can create contraction and expansion of credit selling and buying securities. It can control the credit money by selling securities and eligible papers in the open market. When it sells securities money flows to Central Bank. It reduces the volume of deposit received by the commercial banks and contracts credit. It expands credit by buying securities from the market. It results in large volume of circulation of money among commercial banks.

Open market policy technique is superior to Bank rate policy. First of all bank need not depend upon commercial banks for the success of open market operation. By knowing their reserve position. Central Bank of India can directly influence the commercial banks. Secondly, Open market operations successful when government borrows money from public debt has been expanding, Government can successfully sell its securities to the public.

3) Varying cash reserve ratio: This is another weapon used by the Central Bank to control credit. Cash reserve is the ratio upon which all commercial bank. It is a legal tradition which every commercial bank has to follow. The reserves left with commercial banks after meeting minimum reserve is known as excess reserves. Thus has a direct impact on the capacity of banks to create credit. When the Central Bank raises the cash reserve ratio, the ability of the commercial banks to create credit. When the cash reserve ratio is brought down, the ability of commercial banks to create credit widens.

B) Qualitative Method:

It refers to the step aimed at controlling credit by checking the allocation of credit. Such steps check the purpose for which credit money is used. They encourage credit money for socially desirable purposes and restrict the same towards undesirable and non productive areas.

1) Issuing directives: a) Purposes on which advances can be granted. b) Margin requirements against securities. c) Maximum limit regarding advances granted to any borrower. d) Terms and conditions including the rate of interest for granting loans.

2) Margin requirements: A bank requires security such as gold, shares, property against loan sanction. No bank gives loan equal to the market value of the property, if a person produces security worth Rs. 30,000, he may be got a loan of Rs. 25,000. Thus, difference between the value of security and the actual amount loan is taken as margin. It may direct the commercial bank to keep higher margin towards loan against stock of food grains, equity shares, etc.

3) Regulation of consumer credit: Commercial bank often advance loan to consumer for durable luxury goods like Television, Refrigerator, etc. Central Bank can regulate consumer loans by minimum down payment and increase the period of repayment i.e. installment may be reduce.

4) Rationing of credit: Central bank can also regulate the volume of credit by imposing ceiling on different type of loans provided by the commercial banks, It check the flow of money into undesirable uses.

5) Moral situation: It refers to the general appeal or request made by the central bank persuading the commercial bank to co-operative in controlling credit, Central bank may request the commercial bank to seek further accommodation or not to speculative activities.

6) Direct action: The Central bank also applying to hard measure to control the erring commercial bank. Such as commercial bank refusal of renewal suspending of license, refusing financial assistance to commercial bank etc.

Q8) Explain quantity theory of money.

A8) Quantity Theory of Money:

The quantity theory of money states that the quantity of money is the main determinant of the price level or the value of money. Any change within the quantity of money produces an exactly proportionate change within the price level.

In the words of Irving Fisher, “Other things remaining unchanged, because the quantity of money in circulation increases, the worth level also increases in direct proportion and therefore the value of money decreases and the other way around .”

If the number of cash is doubled, the price level also will double and the value of cash will be one half. On the opposite hand, if the number of cash is reduced by one half, the price level also will be reduced by one half and therefore the value of money will be twice.

Fisher has explained his theory in terms of his equation of exchange:

PT = MV + M’V’

Where P = price level, or 1/P = the value of money;

M = the total quantity of legal tender money;

V = the speed of circulation of M;

M’ = the total quantity of credit money;

V = the speed of circulation of M’;

T = the total amount of goods and services exchanged for money or transactions performed by money.

This equation equates the demand for money (PT) to supply of money (MV=M’V’). the entire volume of transactions multiplied by the worth level (PT) represents the demand for money. Consistent with Fisher, PT is ∑PQ. In other words, price index (P) multiplied by quantity bought (Q) by the community (∑) gives the entire demand for money.

This equals the entire supply of cash within the community consisting of the quantity of actual money M and its velocity of circulation V plus the entire quantity of credit money M’ and its velocity of circulation V. Thus the entire value of purchases (PT) during a year is measured by MV+M’V. Thus the equation of exchange is PT=MV+M’V’. so as to seek out out the effect of the quantity of money on the price level or the value of money, we write the equation as

PT = MV+M’V

Fisher points out that the price level (P) varies directly as the quantity of money (M+M’), provided the volume of trade (T) and velocity of circulation (V, V’) remain unchanged. the truth of this proposition is evident from the fact that if M and M’ are doubled, while V, V’ and T remain constant, P is also doubled, but the value of money (MP) is reduced to half.

Fisher’s quantity theory of cash is explained with the help of Figure 1 (A) and (B). Panel A of the figure shows the effect of changes within the quantity of money on the worth level. to start with, when the number of cash is M1, the worth level is P1.

When the quantity of cash is doubled to M2, the price level is additionally doubled to P2. Further, when the quantity of cash is increased four-fold to M4, the price level also increases by four times to P4. This relationship is expressed by the curve P=f (M) from the origin at 45°.

Assumptions of the Theory:

Fisher’s theory is based on the subsequent assumptions:

1. P is a passive factor in the equation of exchanger which is affected by the other factors.

2. The proportion of M’ to M remains constant.

3. V and V are assumed to be constant and are independent of changes in M and M’.

4. T also remains constant and is independent of other factors like M, M’, V and V’.

5. it's assumed that the demand for money is proportional to the value of transactions.

6. The supply of money is assumed as an exogenously determined constant.

7. The idea is applicable within the end of the day .

8. it's based on the assumption of the existence of full employment in the economy.

Criticisms of the Theory:

The Fisherian quantity theory has been subjected to severe criticisms by economists:

1. Truism:

According to Keynes, “The quantity theory of money may be a truism.” Fisher’s equation of exchange may be a simple truism because it states that the entire quantity of cash (MV+M’V’) paid for goods and services must equal their value (PT). But it can't be accepted today that a particular percentage change within the quantity of money results in an equivalent percentage change within the price level.

2. Other Things not equal:

The direct and proportionate relation between quantity of money and price level in Fisher’s equation is predicated on the idea that “other things remain unchanged”. But in real life, V, V’ and T aren't constant. Moreover, they're not independent of M, M’ and P. Rather, all elements in Fisher’s equation are interrelated and interdependent. as an example , a change in M may cause a change in V.

Consequently, the price level may change more in proportion to a change within the quantity of cash . Similarly, a change in P may cause a change in M. Rise within the price level may necessitate the issue of more money. Moreover, the quantity of transactions T is also suffering from changes in P.

When prices rise or fall, the volume of business transactions also rises or falls. Further, the assumptions that the proportion M’ to M is constant, has not been borne out by facts. Not only this, M and M’ aren't independent of T. a rise within the volume of business transactions requires a rise in the supply of money (M and M’).

3. Constants Relate to Different Time:

Prof. Halm criticizes Fisher for multiplying M and V because M relates to a point of time and V to a period of your time .the former is a static concept and the latter a dynamic. It is, therefore, technically inconsistent to multiply two non-comparable factors.

4. Fails to live Value of Money:

Fisher’s equation doesn't measure the purchasing power of cash but only cash transactions, that is, the quantity of business transactions of all types or what Fisher calls the volume of trade in the community during a year. But the purchasing power of cash (or value of money) relates to transactions for the purchase of goods and services for consumption. Thus the number theory fails to live the value of money.

5. Weak Theory:

According to Crowther, the quantity theory is weak in many respects.

First, it cannot explain ‘why’ there are fluctuations within the price level in the short run.

Second, it gives undue importance to the price level as if changes in prices were the foremost critical and important phenomenon of the economic system.

Third, it places a misleading emphasis on the number of money as the principal cause of changes in the price level during the business cycle . Prices might not rise despite increase within the quantity of money during depression; and that they may not decline with reduction in the quantity of money during boom.

Further, low prices during depression aren't caused by shortage of quantity of cash , and high prices during prosperity aren't caused by abundance of quantity of money. Thus, “the quantity theory is at the best an imperfect guide to the causes of the business cycle in the short period,” according to Crowther.

6. Neglects Interest Rate:

One of the main weaknesses of Fisher’s quantity theory of money is that it neglects the role of the speed of interest together of the causative factors between money and costs . Fisher’s equation of exchange is said to an equilibrium situation during which rate of interest is independent of the quantity of money.

7. Unrealistic Assumptions:

Keynes in his General Theory severely criticized the Fisherian quantity theory of cash for its unrealistic assumptions.

First, the quantity theory of money is unrealistic because it analyses the relation between M and P within the end of the day . Thus it neglects the short run factors which influence this relationship.

Second, Fisher’s equation holds good under the idea of full employment. But Keynes regards full employment as a special situation. the overall situation is one among the underemployment equilibrium.

Third, Keynes doesn't believe that the relationship between the number of cash and the price level is direct and proportional. Rather, it's an indirect one via the speed of interest and the level of output.

According to Keynes, “So long as there's unemployment, output and employment will change in the s.ame proportion as the quantity of money, and when there's full employment prices will change within the same proportion because the quantity of money.”

Thus Keynes integrated the idea of output with value theory and monetary theory and criticised Fisher for dividing economics “into two compartments with no doors and windows between the theory of value and theory of money and prices.”

8. V not Constant:

Further, Keynes acknowledged that when there's underemployment equilibrium, the speed of circulation of money V is very unstable and would change with changes in the stock of money or money income. Thus it was unrealistic for Fisher to assume V to be constant and independent of M.

Q9) Explain cash balance approach.

A9) Cash Balance Approach: Marshall, Pigou, Robertson and Keynes:

As an alternate to Fisher’s quantity theory of money, Cambridge economists Marshall, Pigou, Robertson and Keynes formulated the cash balances approach. Like value theory, they regarded the determination of value of money in terms of supply and demand.

Robertson wrote during this connection: “Money is only one among the various economic things. Its value, therefore, is primarily determined by precisely the same two factors as determine the value of the other thing, namely, the conditions of demand for it, and the quantity of it available.”

The supply of money is exogenously determined at a point of time by the banking system. Therefore, the concept of velocity of circulation is altogether discarded within the cash balances approach because it ‘obscures the motives and decisions of people behind it’.

On the other hand, the concept of demand for money plays the main role in determining the value of money. The demand for money is that the demand to hold cash balances for transactions and precautionary motives.

Thus the cash balances approach considers the demand for money not as a medium of exchange but as a store useful . Robertson expressed this distinction as money “on the wings” and money “sitting”. it's “money sitting” that reflects the demand for money within the Cambridge equations.

The Cambridge equations show that given the supply of money at a point of time, the value of money is decided by the demand for cash balances. When the demand for money increases, people will reduce their expenditures on goods and services so as to have larger cash holdings. Reduced demand for goods and services will bring down the price level and raise the value of money. On the contrary, fall within the demand for money will raise the worth level and lower the value of money.

The Cambridge cash balances equations of Marshall, Pigou, Robertson and Keynes are discussed as under:

Marshall equation:

Marshall didn't put his theory in equation form and it was for his followers to explain it algebraically. Friedman has explained Marshall’s views thus: “As a primary approximation, we may suppose that the amount one wants to carry bears some reference to one’s income, since that determines the quantity of purchases and sales in which one is engaged. We then add up the cash balances held by all holders of money within the community and express the entire as a fraction of their total income.”

Thus we will write:

M = kPY

where M stands for the exogenously determined supply of money, k is that the fraction of the real money income (PY) which people wish to hold in cash and demand deposits, P is the price level, and Y is that the aggregate real income of the community. Thus the price level P = M/kY or the value of money (the reciprocal of price level) is

1/P = kY/M

Pigou:

Pigou was the primary Cambridge economist to express the cash balances approach in the form of an equation:

P = kR/M

where P is that the purchasing power of cash or the value of money (the reciprocal of the price level), k is that the proportion of total real resources or income (R) which people wish to hold in the form of titles to legal tender, R is that the total resources (expressed in terms of wheat), or real income, and M refers to the number of actual units of tender money.

The demand for money, consistent with Pigou, consists not only of legal money or cash but also bank notes and bank balances. so as to incorporate bank notes and bank balances within the demand for money, Pigou modifies his equation as

P = kR/M {c + h(1-c)}

where c is the proportion of total real income actually held by people in legal tender including token coins, (1-c) is that the proportion kept in bank notes and bank balances, and h is that the proportion of actual tender that bankers keep against the notes and balances held by their customers.

Pigou points out that when k and R in the equation P=kR/M and k, R, c and h are taken as constants then the two equations give the demand curve for legal tender as a rectangular hyperbola. this implies that the demand curve for money features a uniform unitary elasticity.

Robertson:

D.H. Robertson gave an equation similar to that of Pigou but with a slight difference. He stated:

P = M/KT

Where, P = price level (of things included in T).

M = the supply of money,

T = total amount of goods and services to be purchased during a year (i.e., the annual volume of transactions),

K = fractional part of T over which people wish to hold command in the form of cash.

It is easy to see that this equation implies that P changes directly as M and inversely as K or T.

This equation is sometimes preferred to that of Pigou’s because of its straight comparability with Fisher’s equation. A similarity may be easily found between the cash transactions equation, P = MV/T and the cash- balances equation of Robertson, P = M/KT.

In the two equations, P, M and T more or less convey the same meanings; and V is reciprocal of K, i.e., V = 1/K. The only difference between the two is that while the former considers the spending of money, the latter takes into account the holding (not spending) of money.

Keynes:

Keynes in his A Tract on Monetary Reform (1923) gave his Real Balances Quantity Equation as an improvement over the opposite Cambridge equations. consistent with him, people always want to have some purchasing power to finance their day to day transactions.

The amount of purchasing power (or demand for money) depends partly on their tastes and habits, and partly on their wealth. Given the tastes, habits, and wealth of the people, their desire to carry money is given. This demand for money is measured by consumption units. A consumption unit is expressed as a basket of standard articles of consumption or other objects of expenditure.

If k is that the number of consumption units within the form of cash, n is that the total currency in circulation, and p is that the price for consumption unit, then the equation is

n= pk

If k is constant, a proportionate increase in n (quantity of money) will cause a proportionate increase in p (price level).

This equation are often expanded by taking into account bank deposits. Let k’ be the number of consumption units in the form of bank deposits, and r the cash reserve ratio of banks, then the expanded equation is

n=p (k + rk’)

Again, if k, k’ and r are constant, p will change in exact proportion to the change in n.

Keynes regards his equation superior to other cash balances equations. the opposite equations fail to point how the worth level (p) can be regulated. Since the cash balances (k) held by the people are outside the control of the monetary authority, p are often regulated by controlling n and r. it's also possible to manage bank deposits k’ by appropriate changes within the bank rate. So p will be controlled by making appropriate changes in n, r and k’ so on offset changes in k.

Q10) Explain Marshall equation and piguo.

A10) Marshall Equation:

Marshall didn't put his theory in equation form and it was for his followers to explain it algebraically. Friedman has explained Marshall’s views thus: “As a primary approximation, we may suppose that the amount one wants to carry bears some reference to one’s income, since that determines the quantity of purchases and sales in which one is engaged. We then add up the cash balances held by all holders of money within the community and express the entire as a fraction of their total income.”

Thus we will write:

M = kPY

where M stands for the exogenously determined supply of money, k is that the fraction of the real money income (PY) which people wish to hold in cash and demand deposits, P is the price level, and Y is that the aggregate real income of the community. Thus the price level P = M/kY or the value of money (the reciprocal of price level) is

1/P = kY/M

Pigou:

Pigou was the primary Cambridge economist to express the cash balances approach in the form of an equation:

P = kR/M

where P is that the purchasing power of cash or the value of money (the reciprocal of the price level), k is that the proportion of total real resources or income (R) which people wish to hold in the form of titles to legal tender, R is that the total resources (expressed in terms of wheat), or real income, and M refers to the number of actual units of tender money.

The demand for money, consistent with Pigou, consists not only of legal money or cash but also bank notes and bank balances. so as to incorporate bank notes and bank balances within the demand for money, Pigou modifies his equation as

P = kR/M {c + h(1-c)}

where c is the proportion of total real income actually held by people in legal tender including token coins, (1-c) is that the proportion kept in bank notes and bank balances, and h is that the proportion of actual tender that bankers keep against the notes and balances held by their customers.

Pigou points out that when k and R in the equation P=kR/M and k, R, c and h are taken as constants then the two equations give the demand curve for legal tender as a rectangular hyperbola. this implies that the demand curve for money features a uniform unitary elasticity.