Unit - 4

Money and National Income

Q1) Define national income.

A1) The output of goods and services that flow from the national production system into the hands of the end consumer in a year."”

On the other hand, in a United Nations report, national income is determined on the basis of a system of estimates of national income, as a net national product, as a supplement to the share of different factors, and as a country & apos; s net national expenditure over a period of one year. In fact, while estimating national income, any of these three definitions could be used, because if different items were correctly included in the estimate, the same national income could be derived.

Q2) How do we measure national income?

A2) National income can be measured by

Q3) What is GNP?

A3) This is the sum of all final goods and services produced in the economy in a year. In W.C.'s words, Peterson, "Gross National Product may be defined as the current market value of all goods and services produced by the economy during the period of income." There are two ways to avoid double counting when estimating GNP.

Q4) Write the formulae of GDP.

A4) GDP (Gross Domestic Product) at market price = production value in a particular year's economy minus intermediate consumption

GDP at Factor Cost = GDP at Market Price-Depreciation + NFIA (Net Factor Revenue from Overseas)-Net Indirect Tax (GNP)

Q5) What is green GDP?

A5) Green Gross Domestic Product, or Green GDP for short, is an indicator of economic growth that takes environmental factors into account along with national standard GDP. Green GDP takes into account the loss and cost of biodiversity due to climate change. Physical indicators such as "annual carbon dioxide" and "waste per capita" may be aggregated into indicators such as "sustainable development indicator

Q6) What is green GNP?

A6) Green GNP - Is an economic and environmental accounting framework that measures national wealth by taking into account depletion of natural resources and environmental degradation and investment in environmental aid.

Q7) What is the Rationale behind Green GDP?

A7) Standard GDP measurements are limited because they are indicators of economic growth and a desirable standard of living. Standard GDP measures only total economic output and there is no way to identify the wealthy or wealthy people that are generated due to economic output. Normal GDP also has no way of knowing if the income levels generated in a country are sustainable. Green GDP is required to overcome this limitation. The capital is not considered relevant and is not well explained in GDP. Policy makers and economic planners do not fully value the potential future benefits of protected environment projects in relation to costs. The positive benefits that can arise from forests and farmlands are not taken into account due to operational difficulties in measuring and valuing such assets. Also, the impact of depletion of natural resources needed to run the economy as described in standard GDP measurements.

Q8) How is Green GDP Calculated?

A8) Green GDP is calculated by subtracting net natural capital consumption from the standard GDP. This includes resource depletion, environmental degradation and protective environmental initiatives. These calculations can alternatively be applied to the net domestic product (NDP), which subtracts the depreciation of capital from GDP. In every case, it is required to convert any resource extraction activity into a monetary value since they are expressed in this manner through national accounts.

Q9) What is NNP?

A9) Net National Product (NNP) is obtained by adjusting depreciation at GNP. As mentioned above, GNP is the sum of the amount of production and the income received by a domestic resident of a country in a year. Over the past year, the available plants and machinery (capital) have been worn and criticized. Such a decrease in capital assets due to wear is measured as "capital depreciation". NNP is obtained by subtracting the value of such depreciation from GNP.

That is GNP - Depreciation = NNP

Q10) What is per capita income (or output)?

A10) Per Capita Income

Per capita income (or) output per person is an indicator to show the living standards of people in a country. If real PCI increases, it is considered to be an improvement in the overall living standard of people. PCI is arrived at by dividing the GDP by the size of population. It is also arrived by making some adjustment with GDP.

GDP=PCI / Total number of people in a country

Q11) What is the meaning of Money?

A11) Money may be anything chosen as the medium of exchange. According to some economist money is anything that performs the function of money. It is something which is widely accepted in payment for goods and services and in settlement of debts. In a modern society for commodities are expressed and valued in terms of money. In a wider sense, the term money includes all medium of exchange – Gold, Silver, Copper, Paper, Cheques, Commercial Bills of exchange, etc.

Q12) State the functions of money.

A12) Functions of Money: -

Money performs various functions. Mainly the functions of money can be classified into three groups’ namely

(i) Primary functions (ii) Secondary function (iii) Contingent functions

1) Primary function: Primary functions are basic or fundamental function of money. In fact, they are the original functions of money which ensure smooth working of the economy. Following are the primary functions:

a) Medium of exchange: Money acts as an effective medium of exchange. It facilitates exchange of goods and services. Everything is bought and sold with help of money. By performing as the medium of exchange, money removes the difficulties of barter system.

b) Measure of value: Money serves as a common measure of value. The value of all goods and services are measured in terms of money. In other words, pieces of all goods and services are expressed in terms money.

2) Secondary function: Secondary functions are those functions which are derived from primary function.

a) Standard of deferred payment: Money acts as an effective standard of deferred payments. Deferred payments refer to payment to be made in future. Deferred payments have become the day-to-day activity in modern society. Money facilitates all kinds of credit transactions. Both, borrowings as well as lending are done in terms of money. All kinds of Hire purchase transactions are carried out in terms of money. As money enjoys the attributes of stability, Durability and General acceptability, it acts as a better standard of deferred payments.

b) Store of value: Money serves as a store of value. Savings were discouraged under the barter system due to lack of store of value. With inventions of money, it is possible to save. At present all savings are done in terms of money. Bank deposits represent the savings of the people. Moreover, money can be easily converted into any other Marketable assets like Land, Machinery, Plant, etc. Thus, it facilitates capital accumulation. Money being the most liquid assets, it acts as a better store of value than any other assets.

c) Transfer of value: Money acts as a means of transferring purchasing power. Money facilitates transfer of value from one person to another person & one place to another place. As money enjoys general acceptability, a person can dispose of his property in Delhi and purchase new property at Mumbai. Instrument like cheques and bank drafts enable such transfer easy and quick.

3) Contingent function: In additions to the above functions, money has to performs certain special function known as contingent functions –

Q13) Explain with The Keynesian Approach: Liquidity Preference:

A13) The Keynesian Approach: Liquidity Preference:

Keynes in his General Theory used a replacement term “liquidity preference” for the demand for money. Keynes suggested three motives which led to the demand for money in an economy: (1) the transactions demand, (2) the precautionary demand, and (3) the speculative demand.

The Transactions Demand for Money:

The transactions demand for money arises from the medium of exchange function of money in making regular payments for goods and services. consistent with Keynes, it relates to “the need of money for the present transactions of private and business exchange” it's further divided into income and business motives. The income motive is supposed “to bridge the interval between the receipt of income and its disbursement.”

Similarly, the business motive is supposed “to bridge the interval between the time of incurring business costs which of the receipt of the sale proceeds.” If the time between the incurring of expenditure and receipt of income is little, less cash is going to be held by the people for current transactions, and the other way around. there’ll, however, be changes within the transactions demand for money depending upon the expectations of income recipients and businessmen. They depend on the level of income, the rate of interest, the business turnover, the traditional period between the receipt and disbursement of income, etc.

Given these factors, the transactions demand for money may be a direct proportional and positive function of the extent of income, and is expressed as

L1 = kY

Where L1 is that the transactions demand for money, k is that the proportion of income which is kept for transactions purposes, and Y is that the income.

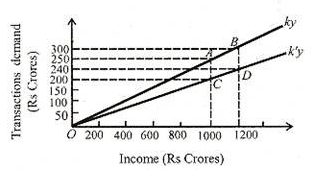

This equation is illustrated in Figure 70.1 where the line kY represents a linear and proportional relation between transactions demand and therefore the level of income. Assuming k= 1/4 and income Rs 1000 crores, the demand for transactions balances would be Rs 250 crores, at point A. With the rise in income to Rs 1200 crores, the transactions demand would be Rs 300 crores at point В on the curve kY.

If the transactions demand falls because of a change in the institutional and structural conditions of the economy, the value of к is reduced to mention, 1/5, and therefore the new transactions demand curve is kY. It shows that for income of Rs 1000 and 1200 crores, transactions balances would Rs 200 and 240 crores at points С and D respectively within the figure. “Thus, we conclude that the chief determinant of changes within the actual amount of the transactions balances held is changes in income. Changes within the transactions balances are the results of movements along a line like kY instead of changes within the slope of the line. within the equation, changes in transactions balances are the results of changes in Y instead of changes in k.”

Interest Rate and Transactions Demand:

Regarding the rate of interest because the determinant of the transactions demand for money Keynes made the LT function interest inelastic. But the acknowledged that the “demand for money within the active circulation is additionally some extent a function of the rate of interest, since a higher rate of interest may cause a more economical use of active balances.” “However, he didn't stress the role of the rate of interest during this a part of his analysis, and lots of some his popularizes ignored it altogether.” In recent years, two post-Keynesian economists William J. Baumol and James Tobin have shown that the rate of interest is a crucial determinant of transactions demand for money.

They have also pointed out the relationship, between transactions demand for money and income isn't linear and proportional. Rather, changes in income result in proportionately smaller changes in transactions demand.

Transactions balances are held because income received once a month isn't spent on the same day. In fact, a private spread his expenditure evenly over the month. Thus, some of cash meant for transactions purposes are often spent on short-term interest-yielding securities. it's possible to “put funds to figure for a matter of days, weeks, or months in interest-bearing securities like U.S. Treasury bills or commercial paper and other short-term money market instruments.

The problem here is that there's a cost involved in buying and selling. One must weigh the financial cost and inconvenience of frequent entry to and exit from the market for securities against the apparent advantage of holding interest-bearing securities in situ of idle transactions balances.

Among other things, the value per purchase and sale, the speed of interest, and therefore the frequency of purchases and sales determine the profitability of switching from ideal transactions balances to earning assets. Nonetheless, with the value per purchase and sale given, there's clearly some rate of interest at which it becomes profitable to modify what otherwise would be transactions balances into interest-bearing securities, albeit the amount that these funds could also be spared from transactions needs is measured only in weeks. the higher the rate of interest, the larger will be the fraction of any given amount of transactions balances which will be profitably diverted into securities.”

The structure of cash and short-term bond holdings is shown in Figure 70.2 (A), (B) and (C). Suppose a private receives Rs 1200 as income on the first of every month and spends it evenly over the month. The month has four weeks. His saving is zero.

Accordingly, his transactions demand for money in each week is Rs 300. So, he has Rs 900 idle money within the first week, Rs 600 within the second week, and Rs 300 within the third week. He will, therefore, convert this idle money into interest bearing bonds, as illustrated in Panel (B) and (C) of Figure 70.2. He keeps and spends Rs 300 during the first week (shown in Panel B), and invests Rs 900 in interest-bearing bonds (shown in Panel C). On the primary day of the second week, he sells bonds worth Rs. 300 to cover cash transactions of the second week and his bond holdings are reduced to Rs 600.

Similarly, he will sell bonds worth Rs 300 within the beginning of the third and keep the remaining bonds amounting to Rs 300 which he will sell on the first day of the fourth week to satisfy his expenses for the last week of the month. the amount of cash held for transactions purposes by the individual during each week is shown in saw-tooth pattern in Panel (B), and therefore the bond holdings in each week are shown in blocks in Panel (C) of Figure 70.2.

The modern view is that the transactions demand for money is a function of both income and interest rates which may be expressed as

L1 = f (Y, r).

This relationship between income and rate of interest and therefore the transactions demand for money for the economy as an entire is illustrated in Figure 3. We saw above that LT = kY. If y=Rs 1200 crores and k= 1/4, then LT = Rs 300 crores.

This is shown as Y1 curve in Figure 70.3. If the income level rises to Rs 1600 crores, the transactions demand also increases to Rs 400 crores, given k = 1/4. Consequently, the transactions demand curve shifts to Y2. The transactions demand curves Y1, and Y2 are interest- inelastic so long because the rate of interest doesn't rise above r8 per cent.

As the rate of interest starts rising above r8, the transactions demand for money becomes interest elastic. It indicates that “given the cost of switching into and out of securities, at rate of interest above 8 per cent is sufficiently high to draw in some amount of transaction balances into securities.” The backward slope of the K, curve shows that at still higher rates, the transaction demand for money declines.

Thus, when the rate of interest rises to r12, the transactions demand declines to Rs 250 crores with an income level of Rs 1200 crores. Similarly, when the value is Rs 1600 crores the transactions demand would decline to Rs 350 crores at r12 rate of interest. Thus, the transactions demand for money varies directly with the level of income and inversely with the speed of interest.

The Precautionary Demand for Money:

The Precautionary motive relates to “the desire to produce for contingencies requiring sudden expenditures and for unforeseen opportunities of advantageous purchases.” Both individuals and businessmen keep take advantage reserve to satisfy unexpected needs. Individuals hold some cash to supply for illness, accidents, unemployment and other unforeseen contingencies.

Similarly, businessmen keep cash in reserve to tide over unfavourable conditions or to gain from unexpected deals. Therefore, “money held under the precautionary motive is very like water kept in reserve during a water tank.” The precautionary demand for money depends upon the level of income, and business activity, opportunities for unexpected profitable deals, availability of cash, the cost of holding liquid assets in bank reserves, etc.

Keynes held that the precautionary demand for money, like transactions demand, was a function of the extent of income. But the post-Keynesian economists believe that like transactions demand, it's inversely associated with high interest rates. The transactions and precautionary demand for money are going to be unstable, particularly if the economy isn't at full employment level and transactions are, therefore, but the maximum, and are liable to fluctuate up or down.

Since precautionary demand, like transactions demand may be a function of income and interest rates, the demand for money for these two purposes is expressed within the single equation LT=f (Y, r)9. Thus, the precautionary demand for money also can be explained diagrammatically in terms of Figures 2 and 3.

The Speculative Demand for Money:

The speculative (or asset or liquidity preference) demand for money is for securing profit from knowing better than the market what the longer term will bring forth”. Individuals and businessmen having funds, after keeping enough for transactions and precautionary purposes, wish to make a speculative gain by investing fettered. Money held for speculative purposes may be a liquid store of value which may be invested at an opportune moment in interest-bearing bonds or securities.

Bond prices and therefore the rate of interest is inversely associated with one another. Low bond prices are indicative of high interest rates, and high bond prices reflect low interest rates. A bond carries a fixed rate of interest. as an example, if a bond of the worth of Rs 100 carries 4 per cent interest and therefore the market rate of interest rises to eight per cent, the worth of this bond falls to Rs 50 within the market. If the market rate of interest falls to 2 per cent, the value of the bond will rise to Rs 200 within the market.

This can be figured out with the assistance of the equation

V = R/r

Where V is that the current market value of a bond, R is that the annual return on the bond, and r is that the rate of return currently earned or the market rate of interest. So, a bond worth Rs 100 (V) and carrying a 4 per cent rate of interest (r), gets an annual return (R) of Rs 4, that is,

V=Rs 4/0.04=Rs 100. When the market rate of interest rises to 8 per cent, then V=Rs 4/0.08=Rs50; when it falls to 2 per cent, then V=Rs 4/0.02=Rs 200.

Thus, individuals and businessmen can gain by buying bonds worth Rs 100 each at the market value of Rs 50 each when the rate of interest is high (8 per cent), and sell them again once they are dearer (Rs 200 each when the speed of interest falls (to 2 per cent).

According to Keynes, it's expectations about changes in bond prices or within the current market rate of interest that determine the speculative demand for money. In explaining the speculative demand for money, Keynes had a normal or critical rate of interest (rc) in mind. If the present rate of interest (r) is above the “critical” rate of interest, businessmen expect it to fall and bond price to rise. They will, therefore, buy bonds to sell them in future when their prices rise so as to realize thereby. At such times, the speculative demand for money would fall. Conversely, if the present rate of interest happens to be below the critical rate, businessmen expect it to rise and bond prices to fall. They will, therefore, sell bonds within the present if they have any, and therefore the speculative demand for money would increase.

Thus, when r > r0, an investor holds all his liquid assets in bonds, and when r < r0 his entire holdings enter money. But when r = r0, he becomes indifferent to carry bonds or money.

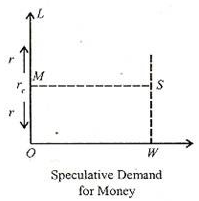

Thus, relationship between an individual’s demand for money and therefore the rate of interest is shown in Figure 70.4 where the horizontal axis shows the individual’s demand for money for speculative purposes and therefore the current and important interest rates on the vertical axis. The figure shows that when r is larger than r0, the asset holder puts all his cash balances in bonds and his demand for money is zero.

This is illustrated by the LM portion of the vertical axis. When r falls below r0, the individual expects more capital losses on bonds as against the interest yield. He, therefore, converts his entire holdings into money, as shown by OW within the figure. This relationship between an individual asset holder’s demand for money and therefore the current rate of interest gives the discontinuous step demand for money curve LMSW.

For the economy as an entire the individual demand curve is often aggregated on this presumption that individual asset-holders differ in their critical rates r0. it's smooth curve which slopes downward from left to right, as shown in Figure 70.5.

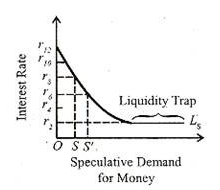

Thus, the speculative demand for money is a decreasing function of the rate of interest. the higher the rate of interest, the lower the speculative demand for money and therefore the lower the rate of interest, the higher the speculative demand for money. It is often expressed algebraically as Ls = f (r), where Ls is that the speculative demand for money and r is that the rate of interest.

Geometrically, it's shows in Figure 70.5. The figure shows that at a very high rate of interest rJ2, the speculative demand for money is zero and businessmen invest their cash holdings fettered because they believe that the rate of interest cannot rise further. because the rate of interest falls to say, r8 the speculative demand for money is OS. With a further fall within the rate of interest to r6, it rises to OS’. Thus, the form of the Ls curve shows that because the rate of interest rises, the speculative demand for money declines; and with the fall in the rate of interest, it increases. Thus, the Keynesian speculative demand for money function is very volatile, depending upon the behaviour of interest rates.

Liquidity Trap:

Keynes visualised conditions during which the speculative demand for money would be highly or maybe totally elastic so that changes within the quantity of money would be fully absorbed into speculative balances. this is often the famous Keynesian liquidity trap. during this case, changes within the quantity of money have no effects in the least on prices or income. according to Keynes, this is often likely to happen when the market rate of interest is very low in order that yields on bond, equities and other securities also will be low.

At a really low rate of interest, like r2, the Ls curve becomes perfectly elastic and therefore the speculative demand for money is infinitely elastic. This portion of the Ls curve is known as the liquidity trap. At such a low rate, people prefer to keep money in cash instead of invest fettered because purchasing bonds will mean a definite loss. People won't buy bonds so long as the rate of interest remain at the low level and that they will be expecting the speed of interest to return to the “normal” level and bond prices to fall.

According to Keynes, because the rate of interest approaches zero, the risk of loss in holding bonds becomes greater. “When the price of bonds has been bid up so high that the rate of interest is, say, only 2 per cent or less, a really small decline within the price of bonds will wipe out the yield entirely and a rather further decline would result in loss of a part of the principal.” Thus, the lower the rate of interest, the smaller the earnings from bonds. Therefore, the greater the demand for cash holdings. Consequently, the Ls curve will become perfectly elastic.

Further, consistent with Keynes, “a long-term rate of interest of two per cent leaves more to fear than to hope, and offers, at an equivalent time, a running yield which is only sufficient to offset a really small measure of fear.” This makes the Ls curve “virtually absolute within the sense that almost everybody prefers cash to holding a debt which yields so low a rate of interest.”

Prof. Modigliani believes that an infinitely elastic Ls curve is possible in a period of great uncertainty when price reductions are anticipated and therefore the tendency to invest in bonds decreases, or if there prevails “a real scarcity of investment outlets that are profitable at rates of interest above the institutional minimum.”

The phenomenon of liquidity trap possesses certain important implications.

First, the monetary authority cannot influence the rate of interest even by following a cheap money policy. a rise within the quantity of cash cannot lead to a further decline within the rate of interest during a liquidity-trap situation. Second, the rate of interest cannot fall to zero.

Third, the policy of a general wage cut can't be efficacious within the face of a perfectly elastic liquidity preference curve, like Ls in Figure 70.5. No doubt, a policy of general wage cut would lower wages and prices, and thus release money from transactions to speculative purpose, the rate of interest would remain unaffected because people would hold money due to the prevalent uncertainty within the money market. Last, if new money is made, it instantly goes into speculative balances and is put into bank vaults or cash boxes rather than being invested. Thus, there's no effect on income. Income can change with none change in the quantity of money. Thus, monetary changes have a weak effect on economic activity under conditions of absolute liquidity preference.

The Total Demand for Money:

According to Keynes, money held for transactions and precautionary purposes is primarily a function of the extent of income, LT=f (F), and therefore the speculative demand for money may be a function of the rate of interest, Ls = f (r). Thus, the total demand for money may be a function of both income and therefore the interest rate:

LT + LS = f (Y) + f (r)

or L = f (Y) + f (r)

or L=f (Y, r)

Where L represents the entire demand for money.

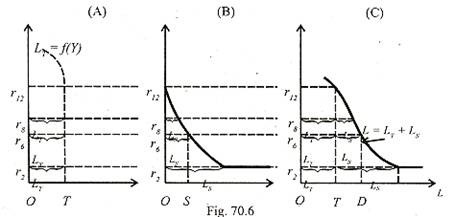

Thus, the entire demand for money can be derived by the lateral summation of the demand function for transactions and precautionary purposes and therefore the demand function for speculative purposes, as illustrated in Figure 70.6 (A), (B) and (C). Panel (A) of the Figure shows ОТ, the transactions and precautionary demand for money at Y level of income and different rates of interest. Panel (B) shows the speculative demand for money at various rates of interest. it's an inverse function of the rate of interest.

For instance, at r6 rate of interest it's OS and as the rate of interest falls to r the Ls curve becomes perfectly elastic. Panel (C) shows the entire demand curve for money L which may be a lateral summation of LT and Ls curves: L=LT+LS. for example, at rb rate of interest, the entire demand for money is OD which is that the sum of transactions and precautionary demand ОТ plus the speculative demand TD, OD=OT+TD. At r2 rate of interest, the total demand for money curve also becomes perfectly elastic, showing the position of liquidity trap.

Q14) Define supply of money.

A14) The supply of money is a stock at a specific point of time, though it conveys the idea of a flow over time. The term ‘the supply of money’ is synonymous with such terms as ‘money stock’, ‘stock of money’, ‘money supply’ and ‘quantity of money’. the supply of money at any moment is that the total amount of money within the economy.

There are three alternative views regarding the definition or measures of money supply. the foremost common view is related to the traditional and Keynesian thinking which stresses the medium of exchange function of cash. consistent with this view, money supply is defined as currency with the general public and demand deposits with commercial banks.

Demand deposits are savings and current accounts of depositors in a commercial bank. they're the liquid kind of money because depositors can draw cheques for any amount lying in their accounts and therefore the bank has got to make cash on demand. Demand deposits with commercial banks plus currency with the general public are together denoted as M1, the money supply. this is often considered a narrower definition of the cash supply.

The second definition is broader and is related to the modem quantity theorists headed by Friedman. Professor Friedman defines the cash supply at any moment of time as “literally the number of dollars people are carrying around in their pockets, the number of dollars they need to their credit at banks or dollars they need to their credit at banks in the form of demand deposits, and also commercial bank time deposits.” Time deposits are fixed deposits of customers in a commercial bank. Such deposits earn a fixed rate of interest varying with the period of time that the amount is deposited. Money can be withdrawn before the expiry of that period by paying a penal rate of interest to the bank.

So, time deposits possess liquidity and are included within the money supply by Friedman. Thus, this definition includes M1 plus time deposits of economic banks within the supply of cash. This wider definition is characterised as M2 in America and M3 in Britain and India. It stresses the store useful function of money or what Friedman says, ‘a temporary abode of purchasing power’.

Q15) What is economic stabilization? Write the objectives of the same.

A15) Economic stabilisation is one among the most remedies to effectively control or eliminate the periodic trade cycles which plague capitalist economy. Economic stabilisation, it should be noted, isn't merely confined to one individual sector of an economy but embraces all its facts. so as to ensure economic stability, variety of economic measures need to be devised and implemented.

In modem times, a programme of economic stabilisation is typically directed towards the attainment of three objectives:

(i) controlling or moderating cyclical fluctuations

(ii) (ii) encouraging and sustaining economic growth at full employment level

(iii) (iii) maintaining the value of money through price stabilisation. Thus, the goal of economic stability is often easily resolved into the dual objectives of sustained full employment and therefore the achievement of a degree of price stability.

Q16) What is monetary policy?

A16) The most commonly advocated policy of solving the matter of fluctuations is monetary policy. Monetary policy pertains to banking and credit, availability of loans to firms and households, interest rates, public debt and its management, and monetary management.

However, the basic problem of monetary policy in reference to trade cycles is to regulate and regulate the quantity of credit in such a way as to attain economic stability. During a depression, credit must be expanded and through an inflationary boom, its flow must be checked.

Monetary management is that the function of the commercial banking system, and thru it, its effects are primarily exerted the economy as an entire. Monetary management directly affects the volume of cash reserves of banks, regulates the availability of money and credit within the economy, thereby influencing the structure of interest rates and availability of credit.

Both these factors affect the components of aggregate demand (consumption plus investment) and therefore the flow of expenditures within the economy. it's obvious that an expansion in bank credit causes an increasing flow of expenditure (in terms of money) and contraction in bank credit reduces it.

Q17) What is fiscal Policy?

A17) Today, foremost among the techniques of stabilisation is fiscal policy. fiscal policy as a tool of economic stability, however, has received its due importance under the influence of Keynesian economies only since Depression years of the 1930s.

The term ‘‘fiscal policy” embraces the tax and expenditure policies of the govt. Thus, fiscal policy operates through the control of state expenditures and tax receipts. It encompasses two separate but related decisions: public expenditures and level and structure of taxes. the quantity of public outlay, the inducement and effects of taxation and therefore the relation between expenditure and revenue exert a major impact upon the free enterprise economy.

Broadly speaking, the taxation policy of the govt relates to the programme of curbing private spending. The expenditure policy, on the opposite hand, deals with the channels by which government spending on new goods and services directly raise aggregate demand and indirectly income through the secondary spending which takes place on account of the multiplier effect.

Taxation, on the opposite hand, operates to scale back the level of personal spending (on both consumption and investment) by reducing the income and therefore the resulting savings within the community. Hence, under the budgetary phenomenon, public expenditure and revenue are often combined in various ways to realize the specified stimulating or deflationary effect on aggregate demand.

Thus, fiscal policy has quantitative also as qualitative aspect changes in tax rates, the structure of taxation and its incidence influence the volume and direction or private spending in economy. Similarly, changes in government’s expenditures and its structure of allocations also will have quantitative and redistributive effects on time, consumption and aggregate demand of the community.

Q18) What is public finance?

A18) The economics of public finance is fundamentally concerned with the technique of rising and dispersion of dollars for the functioning of the government. Thus, the find out about of public revenue and public expenditure constitutes the principal division in the find out about of public finance.

But with these two symmetrical branches of public finance, the hassle of business enterprise of elevating and disbursing of assets additionally arises.

It has also to resolve the query of what is to be performed in case public expenditure exceeds the revenues of the state. In solving the first problem, “financial administration” Comes into the picture. In the latter problem, obviously, the technique of public borrowings or the mechanism of public debt is to be studied. Since both public debt as well as financial administration offers upward jab to a variety of distinctive problems, these are conventionally handled as a separate branch of the subject.

Q19) Write the scope of public finance.

A19) The scope of public finance

The scope of public finance is not just to find out about the composition of public income and public expenditure. It covers a full discussion of the have an impact on of government fiscal operations on the stage of typical activity, employment, costs and increase system of the financial device as a whole. According to Musgrave, the scope of public finance embraces the following three functions of the government’s budgetary coverage limited to the fiscal department:

(i) the allocation branch,

(ii) the distribution branch, and

(iii) the stabilisation branch.

These refer to three goals of finances policy, i.e., the use of fiscal instruments:

(i) to impenetrable adjustments in the allocation of resources,

(ii) to impenetrable changes in the distribution of income and wealth, and

(iii) to achieve financial stabilisation.

Thus, the function of the allocation department of the fiscal branch is to decide what changes in allocation are needed, who shall endure the cost, what income and expenditure policies to be formulated to fulfill the desired objectives.

The characteristic of the distribution department is to decide what steps are needed to carry about the favored or equitable nation of distribution in the economy and the stabilisation branch shall confine itself to the choices as to what ought to be carried out to tightly closed charge steadiness and to keep full employment level.

Further, modern public finance has two aspects:

(i) positive aspect and (ii) normative aspect.

In its advantageous aspect, the study of public finance is concerned with what are sources of public revenue, gadgets of public expenditure, constituents of budget, and formal as nicely as tremendous incidence of the fiscal operations.

In its normative aspect, norms or standards of the government’s monetary operations are laid down, investigated, and appraised. The simple norm of modern finance is normal economic welfare. On normative consideration, public finance turns into a skillful art, whereas in its nice aspect, it remains a fiscal science.

Q20) Explain Welfare Economics?

A20) Welfare economics is a study of how the allocation of resources and goods affects social welfare. This is directly related to the study of economic efficiency and income distribution, and how these two factors affect the overall well-being of people in the economy. In fact, welfare economists seek to provide tools to guide public policy to achieve social and economic outcomes that are beneficial to society as a whole. However, welfare economics is a subjective study that relies heavily on selected assumptions regarding how the welfare of individuals and society as a whole can be defined, measured and compared.

Welfare economics begins with the application of utility theory in microeconomics. Utility refers to the perceived value associated with a particular product or service. In mainstream microeconomic theory, individuals seek to maximize utility through behavioral and consumption choices, and the interaction of buyers and sellers with the laws of supply and demand in competitive markets creates consumer and producer surplus.

A microeconomic comparison of consumer and producer surplus in markets under different market structures and conditions constitutes a basic version of welfare economics. The simplest version of welfare economics is "Which market structure and allocation of economic resources across individuals and production processes maximizes the total utility received by all individuals, or consumers and production across all markets. Do you want to maximize the total surplus of the person? " ?? Welfare economics seeks economic conditions that produce the highest levels of social satisfaction among its members.